Treatment of Compulsive Hoarding

Abstract

Compulsive hoarding and saving symptoms, found in many patients who have obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), are part of a clinical syndrome that has been associated with poor response to antiobsessional medications and cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT). Specific CBT strategies targeting the characteristic features of the compulsive hoarding syndrome have had better results. This article provides an overview of the compulsive hoarding syndrome, a review of treatment approaches and their efficacy, a case presentation, and a detailed discussion of intensive, multimodal CBT for compulsive hoarding. New insights into the neurobiological characteristics of compulsive hoarding that might direct future treatment development are also presented.

(Reprinted with permission from the Journal of Clinical Psychology 2004; 60(11): 1143–1154)

Although standard diagnostic classifications consider obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) to be a single entity, clearly several different symptom dimensions of OCD exist. Four principal OCD symptom factors have been identified as (1) aggressive, sexual, and religious obsessions with checking compulsions; (2) symmetry/order obsessions with ordering, arranging, and repeating compulsions; (3) contamination obsessions with washing and cleaning compulsions; and (4) hoarding and saving symptoms (Leckman et al., 1997). These symptom dimensions appear to be stable over time and show different patterns of genetic inheritance, comorbidity, and treatment response. Thus, OCD appears to be a multidimensional and heterogeneous disorder.

Hoarding is defined as the acquisition of, and inability to discard, worthless items, though they appear to others to have no value (Frost & Gross, 1993). Hoarding and saving behavior has been observed in several neuropsychiatric disorders, including schizophrenia, dementia, eating disorders, and mental retardation, as well as in nonclinical populations, but it is most commonly found in patients who have OCD. Among OCD patients, 18–42% have hoarding and saving compulsions. Hoarding and saving symptoms are part of a discrete clinical syndrome that also includes indecisiveness, perfectionism, procrastination, difficulty in organizing tasks, and avoidance (Frost & Hartl, 1996; Steketee & Frost, 2003). OCD patients who have hoarding and saving as their most prominent and distressing symptom dimension of OCD and show the other associated symptoms are thus considered to have the “compulsive hoarding syndrome” (Saxena et al., 2002; Steketee & Frost, 2003).

Compulsive hoarding is most commonly driven by obsessional fears of losing important items that the patient believes will be needed, distorted beliefs about the importance of possessions, and excessive emotional attachments to possessions (Frost & Hartl, 1996). Hoarders usually fear making wrong decisions about what to discard and what to keep, so they acquire and save items to prepare for every imaginable contingency. Two types of saving have been identified: instrumental saving, in which possessions fulfill a specific desire or purpose, and sentimental saving, in which possessions represent extensions of the self. By saving possessions, the compulsive hoarder postpones making the decision to discard something and, therefore, avoids experiencing anxiety about making a mistake or being less than perfectly prepared. The most commonly saved items include newspapers, magazines, old clothing, bags, books, mail, notes, and lists (Frost & Gross, 1993; Winsberg et al., 1999). Living spaces become sufficiently cluttered to preclude the activities for which they were designed, causing significant impairment in social and/or occupational functioning (Frost & Gross, 1993).

Only a few studies have directly compared patients who have the compulsive hoarding syndrome to nonhoarding OCD patients; all have found greater functional disability and more severe psychopathology in hoarders. Compared to nonhoarding OCD patients, hoarders have more severe anxiety, depression, personality disorder symptoms, and family and social disability (Steketee & Frost, 2003) and lower global functioning (Saxena et al., 2002). Compulsive hoarders are less likely to be married than nonhoarders, a finding that indicates greater social dysfunction (Steketee & Frost, 2003). A study of elderly hoarders found that hoarding constituted a physical health threat to 81% of them, including threat of fire hazard, falling, unsanitary conditions, and inability to prepare food. Hoarders often have less insight into their symptoms than nonhoarding OCD patients, making them less likely to seek treatment. Taken together, the research indicates that compulsive hoarders have a unique behavioral profile and a characteristic pattern of symptoms and disability.

Genetic and family studies suggest that compulsive hoarding has a different pattern of genetic inheritance and comorbidity than other OCD symptom factors. The hoarding/ saving symptom factor shows an autosomal recessive inheritance pattern and has been associated with genetic markers on chromosomes 4, 5, and 17 (Zhang et al., 2002). One study found that 84% of compulsive hoarders reported a family history of hoarding behaviors in at least one first-degree relative, but only 37% reported a family history of OCD (Winsberg et al., 1999). Compared with nonhoarding OCD probands, compulsive hoarders have been found to have a greater prevalence of social phobia, personality disorders, and pathological grooming disorders and higher rates of hoarding and tics in first-degree relatives. These studies indicate that the compulsive hoarding syndrome may represent an etiologically distinct subgroup or variant of OCD (Black et al., 1998).

CLINICAL PICTURE

A thorough assessment of patients' history and clinical presentation, with particular attention to the unique symptoms of the compulsive hoarding syndrome, is a prerequisite for effective treatment.

AMOUNT OF CLUTTER

Clutter may extend beyond a patient's home and may be found in automobiles, garages, storage lockers, and even storage areas belonging to friends and family. Living areas may be so cluttered that normal activities, such as sleeping in a bed, sitting on couches, or using a kitchen counter, are impossible.

BELIEFS ABOUT POSSESSIONS

Compulsive hoarders often feel very responsible for what happens to their possessions and go to great lengths to avoid being wasteful or irresponsible in the disposition of their belongings. Some believe that every item has special significance. Hoarders also frequently have unattainable expectations of perfection, believing they must be vigilant in not losing any opportunity to improve preparedness. Compulsive hoarders often believe that their memory is poor and, therefore, they have to keep their belongings in sight because they would not otherwise remember where they were.

INFORMATION PROCESSING DEFICITS

Compulsive hoarders have great difficulty making decisions and categorizing possessions. Because every item feels unique, they create a special category for each one and resist storing them together. Many hoarders also report marked distractibility and difficulty in maintaining attention on tasks.

AVOIDANCE BEHAVIORS

In addition to avoiding discarding items and making decisions, compulsive hoarders may avoid routine tasks such as sorting mail, returning calls, or washing dishes. They may even avoid legally necessary tasks such as paying bills, rent, and taxes.

DAILY FUNCTIONING

Because of their desires for perfection, compulsive hoarders frequently take a long time to complete even small chores. An inordinate amount of time may be spent “churning”—moving items from one pile to another but never actually discarding any item nor establishing any consistent organizational system. Daily rhythms are often disrupted. Many compulsive hoarders whom we have seen sleep most of the day and are awake at night. Many patients also do not have consistent eating patterns.

MEDICATION COMPLIANCE

Because of their unstructured days and erratic sleep/wake cycles, compulsive hoarders often forget to take their medications or take them at inappropriate times. They may run out of medications or lose them among the clutter and not renew their prescriptions for days or weeks.

LEVEL OF INSIGHT

Many compulsive hoarders have poor insight into their disorder, with little awareness of how much hoarding and clutter have impacted their life. Poor insight also contributes to low motivation for treatment. Despite significant pressure from loved ones or authorities to get help, many hoarders are not convinced they truly have a psychiatric disorder. Therefore, they may be quite ambivalent about engaging in treatment or refuse it outright.

SOCIAL AND OCCUPATIONAL FUNCTIONING

Many compulsive hoarders have very little family or social support. The nature of their problem makes them socially isolated. They are frequently too embarrassed by their clutter to invite people to their home, sometimes for many years. Work performance is also often impaired.

TREATMENT APPROACHES FOR COMPULSIVE HOARDING

PHARMACOTHERAPY

Effective treatments for OCD include serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SRI) medications and cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) using the technique of exposure and response prevention (ERP). Hoarding and saving compulsions have been strongly associated with poor response to SRIs (Black et al., 1998; Winsberg et al., 1999; Mataix-Cols et al., 1999). A small study using open treatment with paroxetine or CBT for OCD patients found that nonresponders were significantly more likely to have hoarding/saving symptoms than responders (Black et al., 1998). In a case series, only 1 of 18 compulsive hoarders treated with a variety of SRIs had an adequate response, and 9 had no response (Winsberg et al., 1999). In an analysis of large scale, controlled trials of SRI treatment for patients who have OCD, higher scores on the hoarding symptom dimension predicted poorer response to SRI treatment, after controlling for baseline severity (Mataix-Cols et al., 1999). Thus, the hoarding phenotype is a clear predictor of poor response to standard antiobsessional medications. Despite this fact, no pharmacotherapeutic study has specifically targeted the compulsive hoarding syndrome.

COGNITIVE-BEHAVIORAL THERAPY

Hoarding and saving symptoms have been associated with poor response to CBT, but compulsive hoarders have been underrepresented in most CBT studies of OCD, limiting the generalizability of the results. Only a few studies have reported the response of compulsive hoarders to ERP. Most of this literature is in the form of case reports, the majority of which report a poor outcome and usually emphasize compulsive hoarders' ambivalence toward treatment, poor insight, and failure to resist hoarding compulsions. In a controlled trial of CBT for patients who have OCD, high hoarding symptom scores predicted premature dropout and poor response to treatment (Mataix-Cols et al., 2002).

There is a paucity of literature on CBT that specifically targets compulsive hoarding. One group of researchers has developed a CBT treatment strategy (Hartl & Frost, 1999; Steketee & Frost, 2000) on the basis of a cognitive-behavioral model that conceptualizes compulsive hoarding as involving four main problem areas: information processing deficits, problems in forming emotional attachments, behavioral avoidance, and erroneous beliefs about the nature of possessions (Frost & Hartl, 1996). CBT for compulsive hoarding is directed toward decreasing clutter, improving decision-making and organizational skills, and strengthening resistance to urges to save. Treatment includes ERP, excavation of saved material, decision-making training, and cognitive restructuring. They first reported the success of their treatment strategy in a single patient (Hartl & Frost, 1999). After 9 months of treatment, indecisiveness, hoarding, and OCD symptom severity were all reduced. Over a 17-month period, five rooms were excavated. They then reported on seven compulsive hoarders treated with group CBT sessions and individual home visits. After 20 weeks of treatment, five of the seven patients had noticeable improvement, with significantly reduced acquisition of items, increased awareness of irrational reasons for saving, and improved organizational skills (Steketee & Frost, 2000). Treatment continued for several of these patients for up to 1 year, with continued improvement. This pilot study also demonstrated the needs to address difficulties with patient motivation and involve family members in order to promote progress and reduce risk of relapse. Although clearly effective, this type of treatment is lengthy and labor-intensive.

INTENSIVE MULTIMODAL TREATMENT

Although not all studies agree, recent research suggests that the combination of medications and CBT is superior to either alone for OCD. Intensive treatment approaches combining aggressive pharmacotherapy with daily CBT and psychosocial rehabilitation in controlled settings have been found to be effective for severe, treatment-refractory OCD.

The UCLA OCD Partial Hospitalization Program (PHP) is a specialized treatment program that provides intensive, multimodal treatment for severely ill patients who have OCD and related disorders. Compared with outpatient treatment, this program has the advantages of strict enforcement of compliance with medication and CBT, as well as massed ERP on a daily basis, 5 days a week. The UCLA OCD PHP utilizes a modified version of the treatment approach designed by Frost and colleagues for patients who have the compulsive hoarding syndrome.

We sought to determine how compulsive hoarders would respond to intensive, multimodal treatment in the UCLA OCD PHP. We studied 190 consecutive patients with DSM-IV OCD, 20 of whom were classified as having the compulsive hoarding syndrome. All patients received intensive, daily CBT (in both individual and group formats), several hours a day, for approximately 6 weeks, and the vast majority received medications and psychosocial rehabilitation. All patients were assessed before and after treatment with the Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS), Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS), and Hamilton Anxiety Scale (Ham-A). The proportions of patients treated with SRIs and antipsychotic medications did not differ significantly between groups. CBT consisted of individualized ERP, along with cognitive restructuring to improve insight, decrease depressive and general anxiety symptoms, and address distorted beliefs. The 20 compulsive hoarders received CBT focused on the compulsive hoarding syndrome, along with training in organizational skills and time management. We compared the response to treatment of compulsive hoarders (n = 20) versus nonhoarding OCD patients (n = 170).

Hoarders had higher Ham-A scores than nonhoarders, both before and after treatment, but had similar pretreatment Y-BOCS and HDRS scores. Both groups improved significantly with treatment, but nonhoarders had significantly greater decreases in Y-BOCS scores than hoarders, indicating greater improvement of OCD symptoms. Compulsive hoarders continued to have greater overall symptom severity and functional impairment than nonhoarding OCD patients at the time of discharge. However, though many hoarders had failed trials of SRIs or outpatient CBT before admission to the OCD PHP, they responded better than we expected to intensive treatment, with a mean 35% decrease in Y-BOCS score.

MULTIMODAL TREATMENT FOR COMPULSIVE HOARDING IN AN INTENSIVE TREATMENT SETTING

Intensive treatment begins with a thorough assessment of the patient's amount of clutter; beliefs about possessions; information-processing, decision-making and organizational skills; avoidance behaviors; daily functioning; level of insight; motivation for treatment; social and occupational functioning; level of support from friends and family; and medication compliance. Before treatment begins, patients must provide baseline photographs of their cluttered areas.

Education and ERP are major components of treatment. Patients learn to conceptualize their hoarding in terms of problems with anxiety, avoidance, and information processing. Patients then gradually expose themselves to situations that cause them anxiety (e.g., being required to throw something away or make a decision about what to do with a specific object). They rate their subjective level of distress at regular intervals, using a Subjective Units of Distress Scale (SUDS). They are then supported and instructed to resist the urge to save or avoid until their SUDS level diminishes by at least 50%. With repeated practice, ERP extinguishes the fear of losing something important, thereby reducing the strength of the patient's urges to save. Intensive CBT for compulsive hoarding focuses on four main areas: discarding, organizing, preventing incoming clutter, and introducing alternative behaviors.

DISCARDING

From the outset, patients are told that ERP will involve discarding items rather than merely organizing them. Discarding tasks force patients to make decisions rather than postponing them; the result is a decrease in the anxiety associated with decision making. They also help patients learn that nothing terrible happens when they discard items that feel valuable. A secondary benefit to discarding is that patients can learn how to organize their remaining possessions more effectively. When hoarders discard possessions, they typically become anxious, sad, or angry. In our experience, SUDS levels decrease faster when patients do not see their items once they are discarded. Discarding tasks may be performed in the patient's home or in the therapist's office. When treatment occurs in the home, patients are asked to pick one room on which they would most like to work. They then systematically work their way around the room, discarding items or storing them appropriately as they go. They should not move on to another room until the first is completely cleared of clutter. Patients who live too far away from home to make home visits feasible are instructed to take boxes of clutter from their specified room to the therapist's office and do the discarding and sorting there.

There are several ground rules of discarding: The first is that patients must pick up the first item that comes to hand in their pile of clutter, rather than sifting through the pile. The second rule is that they must make a decision about that item before they move on to the next item. Patients have three choices when making a decision about an item—they can discard it, keep it, or recycle it. The preferred option is that the patient discard the item, and he or she is actively encouraged to provoke anxiety by throwing away as many items away as possible. If patients decide that they must keep an item, they must decide where the item will be stored. Recycling items is acceptable, as long as the recycling options are limited.

ERP is bolstered by cognitive restructuring. Patients are prompted to reframe their obsessive fears about discarding things. They are asked, “What's the worst thing that could happen if you didn't have this item?” “What do you think other people do with similar items?” “If you threw this information away now, how could you access it if you found that you needed it in the future?” Compulsive hoarders need assistance in learning how to think differently about their possessions. When patients are asked to think about the consequences of throwing away their clutter, they are challenging their erroneous beliefs that dire consequences will occur if they discard something. At the start of treatment, when patient and therapist look at the baseline photographs of their clutter, patients are asked about what their ideal home would look like. They are asked what percentage of their possessions would have to be removed in order to achieve that ideal. Throughout treatment, patients are reminded of how much clutter they have to eliminate in order to achieve their ideal living environment.

ORGANIZING

Many compulsive hoarders have as much difficulty organizing and storing their possessions as they have discarding them. Patients must identify specific places to store saved items and designate deadlines by which storage will be completed. They are taught more efficient strategies for organizing their possessions. Once an area is cleared of clutter, it must be maintained. Patients are encouraged to use the cleared area for its intended purpose.

PREVENTING INCOMING CLUTTER

Clutter should not enter as fast as it leaves. Therefore, patients must work on resisting the urge to acquire new items. Patients are asked to keep a daily log of every item that they acquire or purchase, which builds awareness of triggers and patterns of acquisition behaviors. They are encouraged to discontinue many of their subscriptions to magazines and newsletters. If patients have difficulty going into stores without buying items, they receive graduated assignments to go to stores and resist the urge to buy.

INTRODUCING ALTERNATIVE BEHAVIORS

Hoarding tends to be a full-time occupation. It is important to replace hoarding behaviors with more adaptive behaviors. This is done in several ways: First, although many compulsive hoarders dislike the idea of schedules, they benefit from structure in their day. Scheduling the day helps patients develop the habit of taking medications regularly, going to sleep at appropriate times, and being active during the day. These changes can contribute greatly to improved mood and functioning. Second, patients are required to perform activities that were previously avoided, such as washing laundry, emptying the trash, and sorting mail on a regular basis. Patients are encouraged to designate specific days and times for each activity. As treatment progresses, patients start working toward more long-term structure, which may include part-time work, volunteer work, or enrollment in classes. It is also important that they incorporate recreational time in each day. Compulsive hoarders often report that they never have time to relax or pursue their hobbies. Therefore, patients are taught to create a realistic schedule of activities that includes their chores, CBT homework assignments, recreational activities, and eating and sleeping times.

ENDING TREATMENT

It is highly motivating at the end of treatment to have “after” photos of the areas on which patients have worked. When placed next to the baseline photos, they enable patients to appreciate the improvements they have made and provide a visual reminder of the benefit of their hard work. Patients are strongly encouraged to have follow-up CBT on at least a weekly basis after they complete the intensive treatment program. Without adequate follow up with outpatient treatment, most patients do not maintain the gains they have made in intensive treatment.

CASE ILLUSTRATION

Presenting problem/client description

“Sally” was a 50-year-old married woman who had 3 children and a history of OCD symptoms since childhood. Her symptoms had been worsening since her early 20s and currently took the form of severe compulsive hoarding. Sally also reported mild depressive symptoms. Her family history was significant for compulsive hoarding behaviors in her mother, sister, maternal aunt, middle daughter, and husband.

Sally first sought treatment when she was 49. Treatment with paroxetine (Paxil 50 mg/day) helped relieve Sally's depression significantly but did not improve the hoarding. Despite increased motivation to address her hoarding problem, she did not know where to begin and was still unable to discard items. Outpatient CBT was unsuccessful because Sally usually arrived more than 20 minutes late at each session. She often had many subjects to talk about and had difficulty focusing on the process of sorting or discarding her possessions. She was unable to discard any of her accumulated clutter at home between sessions and was therefore referred to the UCLA OCD PHP for intensive treatment.

CASE FORMULATION

At the time of admission, every room in Sally's house was cluttered, including her children's bedrooms, garage, and garden. She also had a full storage locker. Sally's hoarded possessions included papers, boxes, bags, arts and crafts supplies, tools, her children's old schoolwork, toys, and mementos. She had not allowed people to visit her house in many years, causing distress to her children. Sally also described difficulty in making decisions that had been worsening since college. She always felt busy but never productive and never seemed to complete any chore she set out to do. Sally was frequently late for appointments. At work, she noted that her boss was always trying to keep her “on task.” Sally met DSM-IV criteria for OCD and major depression and was diagnosed with the compulsive hoarding syndrome. Her admission Y-BOCS score was 30, and her 21-item HDRS score was 21. Physical and laboratory exam results revealed no abnormalities or confounding medical conditions.

COURSE OF TREATMENT

Sally received intensive, multimodal treatment in the UCLA OCD PHP, 4 hours per day, 5 days a week, for 6 weeks. Her medication was switched from paroxetine to venlafaxine (Effexor 300 mg/day). At the start of treatment, Sally estimated that to make her house look like her ideal home, she would need to discard 80% of her clutter. Several neighbors had complained to Sally that they had difficulty selling their homes because of her messy home. Although Sally was aware that her house was in need of major repairs, she was unable to ask anyone to appraise her house because of the clutter. A primary motivation for treatment was to make the house clean enough to allow workers to enter and do repairs. She chose to start work on her living room. Because Sally lived far from UCLA, she stayed in a local hotel during the week and returned home on weekends. In the PHP, Sally spent 2 to 3 hours a day sorting through and discarding clutter that she had taken in from home. Her weekend homework was to put those items that she had decided to save in their preassigned places, spending not more than 1 hour per day. Soon Sally was able to go through one box per hour and discard about 80% of her saved possessions with support and prompting from staff. When she worked independently, she had more difficulty—throwing away about 60% of the items. Sally's two main areas of difficulty were discarding items related to her children and discarding old tax-related or legal papers.

To address the challenge of discarding her children's old possessions, PHP staff and Sally met with her children (all college age or older), who agreed that Sally could throw away anything that belonged to them. These included old books, toys, school reports, and photographs. Her children unanimously agreed that it was “all junk,” and if anything was important to them, they would remove it from Sally's boxes of clutter. Despite this strong endorsement from her children, Sally felt that they were too young to appreciate the significance of their possessions and would later regret that they were thrown away. She finally agreed to buy a small trunk for each child and put items that she wanted to keep in the trunk, allowing her children to discard them if they wished. Sally continued to have difficulty with sorting throughout her treatment.

Sally did much better with tax papers and legal forms. At first, she was very reluctant to discard any paper that seemed to be related to legal matters. Because she had become so disorganized over the years, her husband had taken over the payment of bills and management of finances. Sally and her therapist met with Sally's husband to discuss what would be appropriate to keep and what could be discarded. After several weeks of practice, Sally became proficient at making these decisions for herself and did not feel the need to defer to her husband on every item.

OUTCOME AND PROGNOSIS

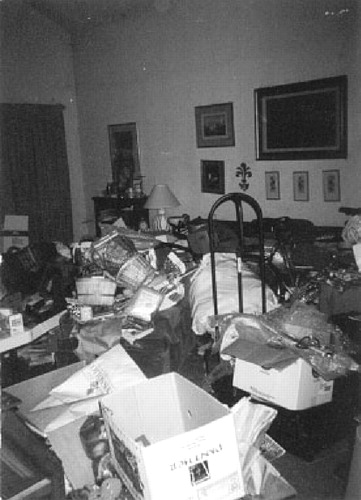

By the end of treatment, Sally had completely cleared her living and dining areas (see photos). Her Y-BOCS score decreased to 16, and her HDRS score was 5. She then continued treatment in an outpatient setting to maintain the gains that she had made in clearing her living and dining areas and start sorting through clutter in another room. Outpatient therapy was set up so that she would assign one afternoon per week as a “therapy” afternoon. She would talk to her therapist by telephone, reviewing behavioral goals for the afternoon, and then work on whatever task was assigned, checking in with her therapist hourly for the next 3 hours. Once a month, Sally would take boxes of clutter from home to her therapist's office and spend a 3-hour session sorting and discarding items.

At 4-month follow-up, Sally's Y-BOCS score had decreased to 14. She was maintaining the gains she had made during the intensive treatment program and had progressed with consistent outpatient CBT. She no longer acquired unnecessary objects and had cleared two more rooms in her home (see Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1. Baseline Photograph of “Sally's” Living Room at the Time of Admission to the UCLA OCD Partial Hospitalization Program.

Figure 2. Sally's Living Room after She Completed Six Weeks of Intensive, Multi-Modal Treatment, Including Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy and Medication, in the UCLA OCD Partial Hospitalization Program.

CLINICAL ISSUES AND SUMMARY

The treatment of compulsive hoarding is extremely difficult. Success depends on the patient's having a high degree of motivation and commitment. Home visits are useful both for initial assessment and for in situ ERP exercises. Our experience suggests that although compulsive hoarders often have a complex array of symptoms and functional deficits, they may respond well to a comprehensive, multimodal approach tailored to the specific features of the compulsive hoarding syndrome. Ideally, multimodal treatment should not only extinguish patients' obsessional fears and compulsive saving behaviors, but also give patients a set of organizational and decision-making skills they will retain forever, thereby reducing the risk of relapse.

There is growing evidence of phenomenological, genetic, and neurobiological heterogeneity within the diagnosis of OCD. Recent data regarding the functional neuroanatomical features of compulsive hoarding shed light on both the phenomenology and the poor treatment response of this syndrome. Our group conducted a positron emission tomography (PET) brain imaging study that measured cerebral glucose metabolism in patients who have the compulsive hoarding syndrome, compared to that in nonhoarding OCD patients and normal controls. We found that compulsive hoarders had a unique pattern of brain activity, distinct from that seen in either nonhoarding OCD patients or normal control subjects. Compulsive hoarders had significantly lower metabolism in the posterior cingulate gyrus and occipital cortex than control subjects. Hoarders and nonhoarding OCD patients also differed from each other: hoarders had significantly lower metabolism in the dorsal anterior cingulate gyrus and thalamus than nonhoarding OCD patients. Across all OCD patients studied, hoarding severity was significantly correlated with lower activity in the dorsal anterior cingulate gyrus (Saxena et al., 2004). Our findings suggest that the compulsive hoarding syndrome may be a neurobiologically distinct variant of OCD.

Diminished activity in the cingulate cortex may contribute both to the symptoms of the compulsive hoarding syndrome and to its poor response to standard antiobsessional treatments. Functions of the anterior cingulate cortex include focused attention, motivation, executive control, assignment of emotional valence to stimuli, monitoring of response conflict, emotional self-control, error detection, and response selection. The anterior cingulate also plays a key role in decision making, especially in choosing among multiple conflicting options. The posterior cingulate cortex is involved in the monitoring of visual events, spatial orientation, episodic memory, and processing of emotional stimuli. Hence, low activity in both the anterior and posterior cingulate gyrus could mediate the remarkable difficulty in making decisions, attentional problems, and other cognitive deficits seen in compulsive hoarders. More-over, lower pretreatment anterior cingulate gyrus activity has been strongly associated with poor response to antidepressant treatment, and lower activity in the posterior cingulate gyrus correlated to a poorer response to fluvoxamine in patients who have OCD. Thus, our finding of low cingulate activity in patients who have the compulsive hoarding syndrome is quite consistent with the poor response to standard treatments for OCD.

Future pharmacotherapeutic approaches should target brain dysfunctions specifically associated with compulsive hoarding (Saxena et al., 2004). Possible strategies might include cognitive enhancers such as donepezil or galantamine, which increase cholinergic neurotransmission in the cerebral cortex, or stimulant medications, which can increase the functioning of medial prefrontal cortical areas involved in attention and executive functioning. Future cognitive-behavioral approaches should also target the information-processing deficits that appear to be present in patients who have the compulsive hoarding syndrome, including faulty decision making and deficits in organization/categorization (Frost & Hartl, 1996). These putative deficits must be confirmed by neuropsychological testing, to determine whether the compulsive hoarding syndrome includes a consistent neurocognitive profile that could be addressed by treatment.

1 Black, D.W., Monahan, P., Gable, J., Blum, N., Clancy, G., & Baker, P. ( 1998). Hoarding and treatment response in non-depressed subjects with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 59, 420– 425.Crossref, Google Scholar

2 Frost, R.O., & Gross, R.C. ( 1993). The hoarding of possessions. Behavior Research and Therapy, 31, 367– 381.Crossref, Google Scholar

3 Frost, R.O., & Hartl, T. ( 1996). A cognitive-behavioral model of compulsive hoarding. Behavior Research and Therapy, 34, 341– 350.Crossref, Google Scholar

4 Hartl, T., & Frost, R.O. ( 1999). Cognitive-behavioral treatment of compulsive hoarding: A multiple baseline experimental case study. Behavior Research and Therapy, 37, 451– 461.Crossref, Google Scholar

5 Leckman, J.F., Grice, D.E., Boardman, J., Zhang, H., Vitale, A., Bondi, C., Alsobrook, J., Peterson, B.S., Cohen, D.J., Rasmussen, S.A., Goodman, W.K., McDougle, C.J., & Pauls, D.L. ( 1997). Symptoms of obsessive-compulsive disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry, 154, 911– 917.Crossref, Google Scholar

6 Mataix-Cols, D., Rauch, S.L., Manzo, P.A., & Jenike, M.A. ( 1999). Use of factor-analyzed symptom dimensions to predict outcome with serotonin reuptake inhibitors and placebo in the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry, 156, 1409– 1416.Google Scholar

7 Mataix-Cols, D., Marks, I.M., Greist, J.H., Kobak, K.A., & Baer, L. (2002). Obsessive-compulsive symptom dimensions as predictors of compliance with and response to behaviour therapy: Results from a controlled trial. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 71, 255– 262.Crossref, Google Scholar

8 Saxena, S., Maidment, K.M., Vapnik, T., Golden, G., Rishwain, T., Rosen, R.M., Tarlow, G., & Bystritsky, A. ( 2002). Obsessive-compulsive hoarding: Symptom severity and response to multi-modal treatment. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 63, 21– 27.Crossref, Google Scholar

9 Saxena, S., Brody, A.L., Maidment, K.M., Smith, E.C., Zohrabi, N., Katz, E., Baker, S.K., & Baxter, L.R. ( 2004). Cerebral glucose metabolism in obsessive-compulsive hoarding. American Journal of Psychiatry, 161, 1038– 1048.Crossref, Google Scholar

10 Steketee, G., & Frost, R.O. ( 2000). Group and individual treatment of compulsive hoarding: A pilot study. Behavioral and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 28, 259– 268.Crossref, Google Scholar

11 Steketee G., & Frost, R.O. ( 2003). Compulsive hoarding: Current status of the research. Clinical Psychology Review, 23, 905– 927.Crossref, Google Scholar

12 Winsberg, M.E., Cassic, K.S., & Koran, L.M. ( 1999). Hoarding in obsessive-compulsive disorder: A report of 20 cases. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 60, 591– 597.Crossref, Google Scholar

13 Zhang, H., Leckman, J.F., Pauls, D.L., Tsai, C.P., Kidd, K.K., Rosario Campos, M., and the Tourette Syndrome Association International Consortium for Genetics. ( 2002). Genomewide scan of hoarding in sib pairs in which both sibs have Gilles de la Tourette Syndrome. American Journal of Human Genetics, 70, 896– 904.Crossref, Google Scholar