Bipolar Disorder Clinical Synthesis: Where Does the Evidence Lead?

Abstract

Bipolar disorder is a common condition diagnosed by the occurrence of pathological mood elevation but most often dominated by dysphoria states. Over the past 10 years, understanding of bipolar disorder and the number of evidence-based treatments have increased dramatically. This article offers strategies for improving diagnostic confidence and simple benchmarks that facilitate integrating principles of evidence-based medicine into the management of patients with bipolar disorder. Simple systematic assessment techniques such as focusing the evaluation to assess the most extreme episode of mood elevation and longitudinal factors such as age of onset and course of illness can avoid errors of omission and raise diagnostic confidence. An iterative measurement-based treatment model that aims to bring patients and their supports into the collaborative care process for progressively better outcomes is recommended.

Clinical context

Bipolar disorders are chronic multidimensional conditions affecting about 3–6% of the population (1–3). The onset of affective episodes usually occurs during adolescence or the early adult years (4, 5) and follows an irregular course in which acute abnormal mood states alternate with periods of full or partial remission. The affective dimension is the cardinal feature of bipolar disorders but is seldom the only expression of these complex brain disorders. In addition to the full syndromal episodes that define mood disorders, patients with bipolar disorders often experience functional impairment due to interepisode subsyndromal affective symptomatology (2, 6), comorbid nonaffective psychopathology (7–16) (e.g., anxiety disorders, substance misuse, and cognitive impairment), and general medical conditions (17–22) (e.g., obesity, migraine headache, and inflammatory disorders).

Bipolar disorder ranks as the sixth leading cause of disability worldwide and is associated with increased mortality (23–25). The excess mortality associated with bipolar disorder is not limited to suicide. Mortality ratios comparing patients with bipolar disorders with the general population reveal elevated death rates due to a number of general medical conditions including heart disease, stroke, and cancer (26, 27).

Diagnosis of bipolar disorder remains an area plagued by uncertainty, despite the often dramatic psychopathology obtained from patients with bipolar disorders. Field trials, however, show that the diagnostic criteria for mania are the most reliable of the DSM-IV diagnoses tested.

The complexity of symptomatology associated with bipolar disorder often leads to confusion and frustration, which undermine confidence in treatment decisions. A basic fund of knowledge related to bipolar disorder and DSM-IV nosology is presented in the following to facilitate the processes of clinical diagnosis and management of bipolar illness. After discussion of these issues, a process is offered to guide integration of clinical knowledge and evidence from clinical trials.

Understanding DSM-IV bipolar disorder nosology

Emil Kraepelin, the father of the modern mood disorder concept, recognized the inherent unreliability of basing psychiatric diagnosis on signs and symptoms. Kraepelin differentiated manic-depressive insanity from dementia and schizophrenia on the basis of longitudinal factors, early age of onset, and course of illness more than cross-sectional symptoms (28). He found manic-depressive illness had a peak onset during the late adolescent and early adult years and observed that periods of illness were characterized by prominent mood symptoms. Kraepelin regarded the differences between patients in which the predominant mood state was euphoria, irritability, or depression as slight in comparison with their similarities, especially the course of illness, which was marked by periods of wellness with full restitution of function. Karl Leonhard attempted to classify psychiatric illness into two large groups on the basis of whether symptoms were consistently of one type or fluctuated between opposite presentations (29). Of the 13 bipolar-type illnesses he proposed, only the distinction of monopolar versus bipolar mood disorders was subsequently validated. The DSM-III divided mood disorders into unipolar and bipolar largely on the basis of family studies, which showed more relatives with bipolar disorders in the families of bipolar probands than in the families of unipolar probands (30, 31).

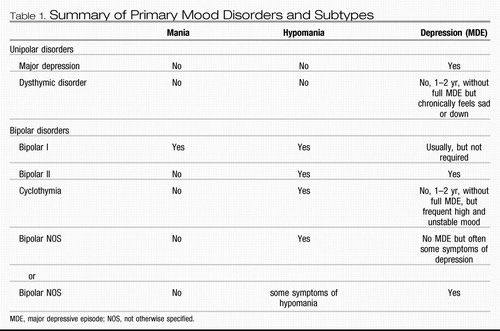

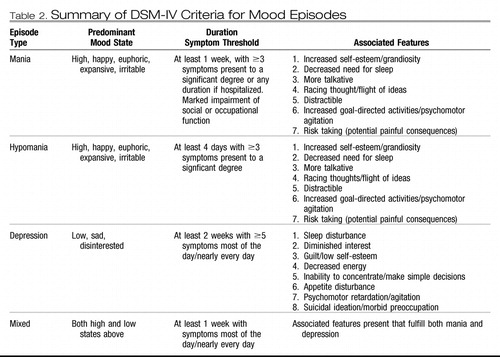

The DSM-III also introduced operational criteria for diagnosis of mania and depression, and the occurrence of a manic episode was used as the defining characteristic of bipolar disorder. The DSM-IV nosology for mood disorders provides criteria for classification at three conceptual levels (32). At the first level, lifetime mood disorder diagnoses, DSM-IV criteria differentiate primary mood disorders into unipolar mood disorder and bipolar mood disorder and their subtypes largely on the basis of the history of diagnosed episodes. Thus, at the second level, criteria that define the discrete abnormal mood states that DSM-IV designates as depression, hypomania, mania, or mixed episodes (for a modified summary see Table 1) are the building blocks underlying diagnosis of lifetime disorder and subtype. The diagnostic feature distinguishing bipolar disorders from other mental disorders is the occurrence of abnormal mood elevation not attributable to substance abuse or a general medical condition. Only a single such episode is required. The occurrence of major depressive episodes and hypomanias comprises the bipolar II diagnosis. If a patient previously diagnosed with bipolar II has an episode meeting the full criteria for mania, the lifetime diagnosis changes to bipolar I. The DSM-IV does not include age of onset or course of illness as diagnostic criteria for mood disorders, and no diagnostic laboratory tests are available (Table 2).

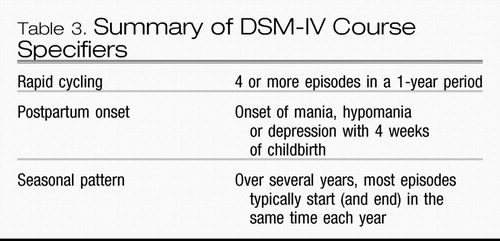

Course specifiers, a third conceptual dimension, are not thought to represent separate pathological conditions; the criteria merely describe common patterns in the course of episodes within the defined DSM-IV mood disorders (Table 3). Rapid cycling requires the occurrence of four episodes or two complete cycles over a 12-month period. Post-partum onset refers to episodes within 4 weeks after childbirth. The seasonal pattern course specifier requires a temporal relationship between onset of episodes and time of year for the majority of episodes over the patient’s lifetime and that no episodes occurred outside the expected interval over the preceding 2 years.

DSM-IV criteria for episodes: the building blocks of lifetime diagnosis

The criteria for DSM-IV mood episodes all require a predominant mood state that persists beyond a defined period of minimum duration during which several associated features must be present at or above a threshold level of intensity. When substance use or a general medical condition is identified as the causative factor producing the mood syndrome, episodes are diagnosed using the same criteria but must be diagnosed as secondary depression, secondary mania, and so on.

Challenges to prompt accurate diagnosis of bipolar disorder

Patient survey results indicate the average patient with bipolar disorder does not receive a proper diagnosis for nearly a decade after the onset of his or her first episode (33, 34). Why is this? Bipolar disorder is diagnosed by the occurrence of pathological mood elevation, but abnormal mood elevation seldom dominates the lifetime course of bipolar disorder, and the faculty required to perceive mood elevation may be impaired by the illness (35).

Mood elevation is subject to poor recall and even when perceived tends to be reported as briefer than reports from observers. The distinction between bipolar I and bipolar II can be difficult. Significant impairment of social or occupational function or hospitalization, the main criteria separating mania and hypomania, may be subjective or reflect non-clinical circumstances such as insurance coverage or the availability of supports.

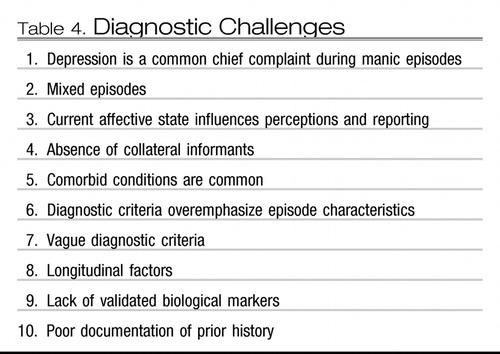

For most patients with bipolar disorder, the clinical picture is made complex because mood episodes are but one manifestation of a complex condition. The diagnosis and treatment of bipolar disorder represent a challenge for the clinician, because the illness is irregular, comorbidity is common, reporting is done through the prism of the current mood state, and DSM-IV criteria for the illness parse mental illness based on current and past signs and symptoms of depression and mania without consideration of other dimensions of illness such as longitudinal factors and family history (Table 4).

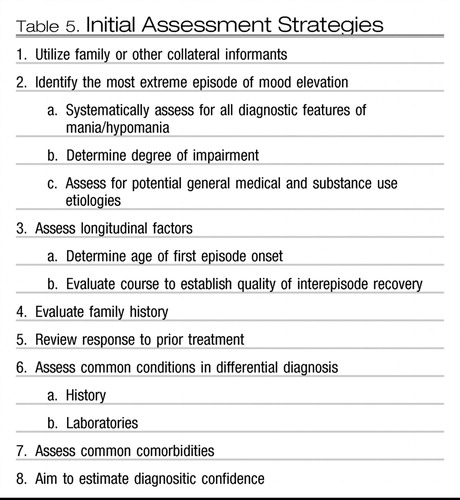

Diagnostic assessment for patients with possible abnormal mood elevation can be greatly simplified by systematic evaluation procedures (Table 5). The Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD) was a National Institutes of Mental Health-sponsored collaboration in which treatment effectiveness was studied in 26 centers across the United States. To better assess the effectiveness of treatments, the STEP-BD treatment centers adopted a common disease management program that consisted of standardized assessment techniques and the collaborative care approach to treatment described below. The systematic record-keeping procedures used in STEP-BD were designed for use in routine clinical practice. The STEP-BD Affective Disorder Evaluation (available at http://www.manicdepressive.org) provides a modular template for evaluating patients, which increases diagnostic confidence by assessing longitudinal factors characteristics of the Kraepelinian conception of manic-depressive illness as well as DSM-IV bipolar disorder.

Every method of differential diagnosis for mood disorders requires characterization of the most extreme episode of mood elevation. The STEP-BD Affective Disorder Evaluation explicitly evaluates whether the most severe identifiable episode meets the criteria for mania, and practicing clinicians focusing their examination in a similar manner can determine whether patients meet the criteria for bipolar I disorder. Most patients (even those who are currently mildly to moderately ill) are able to report sufficient symptoms for the clinician to make a confident diagnosis. Collateral sources aid in the evaluation process and should be included whenever possible. Screening forms such as the Mood Disorder Questionnaire (36) may help identify patients with bipolar disorders but are not a substitute for a thorough diagnostic evaluation. The Mood Disorder Questionnaire is a 15-item self-report inventory that can be completed and scored in less than 5 minutes.

Schema for systematic individualized care

Patients with bipolar disorder enter treatment in different phases of their illness and their presentation changes over time. The multiple dimensions of bipolar illness and the need to shift treatment priorities make it difficult to apply linear algorithms to the management of bipolar disorder.

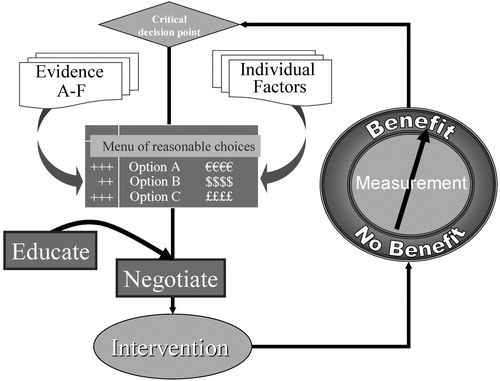

Systematic treatment strategies, can, however, be applied to management of bipolar disorder. After diagnosis, clinical management can be conceptualized as an iterative process in which each follow-up assessment defines decision points for which interventions may be offered (37). Figure 1 offers a general schema for managing iterative clinical care process. The three essential features of this schema are

| • | defining the decision point, | ||||

| • | choosing an intervention, and | ||||

| • | measuring progress. | ||||

The collaborative care disease management model used in STEP-BD provided a system of routine clinical measures in the form of an enhanced progress note and taught clinicians to engage patients as collaborators (38).

STEP-BD added three key elements to the basic schema: 1) A menu of reasonable choices was used as a means of offering patients the range of interventions the clinician judged as appropriate, on the basis of his or her knowledge of the patient and knowledge of the evidence pertaining to the relevant clinical decision point. 2) Education was provided for patients and families in the form of a workbook and DVD. Such durable materials offered patients and their supports the opportunity to participate as informed collaborators in their own care. 3) Clinicians were taught simple negotiation skills. STEP-BD encouraged clinicians to use an adaptation of the paradigm of principled negotiation (39), which aimed to increase the frequency of wise agreements between patient and care providers. The principled negotiation paradigm avoids the adversarial aspects of positional negotiation by applying external standards. In this paradigm, the ratings derived from structured patient self-reports and clinician progress notes provide standards by which the patient and clinician judge the need to revise the treatment plan. The clinician and patient actively engage in a therapeutic alliance to revise the treatment plan in accordance with measured outcomes.

Evidence: benchmarks and metrics

Implicit in the general consensus that the principles of evidence-based medicine provide the best guidance for clinical practice is the idea of offering proven treatments before unproven treatments. Use of this principle necessitates a working knowledge of medical evidence. Consumers of medical evidence can assess the clinical meaning of published studies by evaluating the quality of the evidence and by gauging the effect size of various interventions. Simple metrics are offered below to integrate these processes, basic to evidence-based medicine, into clinical practice.

Although there remain areas for which little or no high-quality data are available, the past decade produced strong growth in the knowledge base pertaining to clinical care of patients with bipolar disorder. The daunting task of transforming the accumulated evidence into useful guidance becomes more manageable and less error prone by limiting consideration to the highest quality studies. Results from studies with sufficient methodological rigor to allow valid causal inference, referred to here as category A evidence, represents the gold standard for evidence-based medicine. Category A evidence can be derived from randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies with adequate sample size. Calculating sample size adequacy is a way of certifying that a study had adequate power to detect statistically significant differences, if, in fact, such differences were present. Formal power calculations can be complicated. A simple rule of thumb is, however, often sufficient to help clinicians judge the adequacy of sample size in mood disorder treatment studies. Clinical trials with fewer than 80 subjects are unlikely to meet the criteria as category A evidence.

This simple benchmark establishes lower bounds on the range of studies we include as having high-quality evidence. Another metric, effect size, is needed, because the convention of declaring results to be statistically significant, if the probability that the differences observed could be produced by chance alone is less than 5%, does not inform us whether an intervention is sufficiently robust to be clinically meaningful (40, 41). Among the methods available to calculate effect size (42), the easiest to use is the number needed to treat (NNT). Calculation of this metric only requires taking the reciprocal of the difference in response rates between treatment groups [NNT = 1/(Response rateactive − Response rateplacebo)]. Thus, if the response rates reported from a study were active treatment = 50% versus placebo = 30%, the reciprocal of 20% = 5. This tells us that to produce one additional positive response beyond what would be produced by placebo treatment, it is necessary to treat five patients.

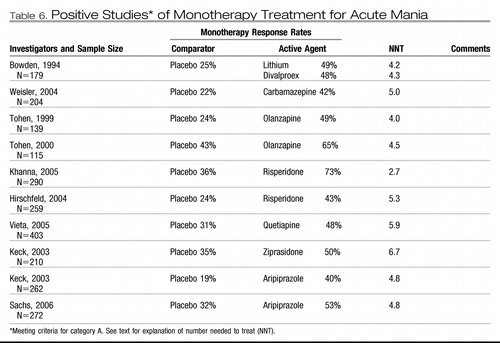

As seen in Table 6, category A evidence is available to support the use of lithium, valproate, carbamazepine, lamotrigine, haloperidol, olanzapine, risperidone, quetiapine, ziprasidone, and aripiprazole. Tables 6 through 9 apply NNT analysis to high-quality studies for acute mania, bipolar depression, and maintenance.

Acute mania: summary of category a data

The category A studies for acute mania (Table 6) demonstrate the efficacy of six dopamine-blocking agents (olanzapine, ziprasidone, risperidone, haloperidol, quetiapine, and aripiprazole) and three non-dopamine-blocking agents (lithium, valproate, and carbamazepine).

This body of evidence offers important clinical guidance that may not be obvious from a review of the individual studies as follows.

| 1. | Patients receiving monotherapy are likely to remain acutely manic despite 3 weeks of treatment. After 3 weeks of treatment under the controlled conditions of a randomized, controlled trial, the mean mania rating scale score for subjects receiving any one of the proven antimanic agents exceeds the minimum required for study entry at baseline. This finding both highlights the need for sustained treatment and provides a rationale for combination treatment. | ||||

| 2. | Although there are undoubtedly individual differences in response to antimanic agents, the preponderance of accumulated evidence does not indicate important differences in overall efficacy. Nearly all direct comparisons between active agents yield no statistically significant differences in overall antimanic efficacy [lithium versus chlorpromazine (43), haloperidol versus risperidone (44), olanzapine versus divalproex (45), olanzapine versus haloperidol (46), aripiprazole versus haloperidol (47), quetiapine versus lithium (48), or quetiapine versus haloperidol (49)]. Two exceptions to this pattern are noteworthy. Tohen et al. (50) found olanzapine to have a small, but statistically significant, efficacy advantage over divalproex. This advantage was, however, at least partially offset by disadvantages in tolerability. Conversely, the comparison of aripiprazole and haloperidol reported by Vieta et al. (47) showed no difference in efficacy, but a significant advantage for aripiprazole in overall effectiveness because of its greater tolerability. | ||||

| 3. | NNT analyses show that it is necessary to treat three to six patients with an antimanic agent to yield one additional responsive patient. The desire to compare results across studies by computing effect size is understandable, but making comparisons of the NNT across studies is of questionable validity. An NNT analysis does correct results for placebo response but does not overcome the methodological limitations that prevent drawing conclusions based on comparisons of treatments not available within the same randomized study. Comparing outcomes across placebo-controlled monotherapy mania studies is confounded by differences in study samples as well as study procedures. For instance, the antimanic efficacy of risperidone appears twice as robust in a study reported from a sample accessioned in India (51) than in a sample of study sites in the United States (52) that used nearly the same treatment protocol. | ||||

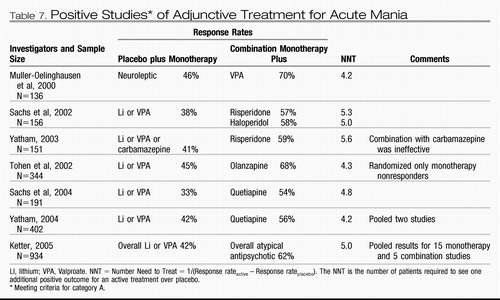

| 4. | Category A studies suggest that addition of a dopamine-blocking antimanic agent confers about the same increment of extra benefit over placebo whether it is administered as an adjunct to valproate or lithium or used as a monotherapy (53, 54). Valproate was also superior to placebo as an adjunct to antipsychotic treatment (55). The data are as yet insufficient to prove that two agents are superior to monotherapy, because the advantage of adding a second active agent has only been demonstrated in patient samples that included patients with inadequate response to prior treatment. Nonetheless, combination treatment is a reasonable approach for more severely ill patients because the preponderance of evidence from these studies shows that dropout rates are lower among subjects receiving two active treatments than among those receiving placebo and one active treatment (56, 57). | ||||

In addition, placebo-controlled adjunct studies have established the efficacy of adding valproate to dopamine-blocking agents and the efficacy of adding risperidone, haloperidol, olanzapine, or quetiapine to the non-dopamine-blocking agents lithium or valproate. Category A placebo-controlled clinical trials comparing gabapentin, lamotrigine, topiramate, and oxcarbazepine with placebo have to date produced only negative results or failed studies.

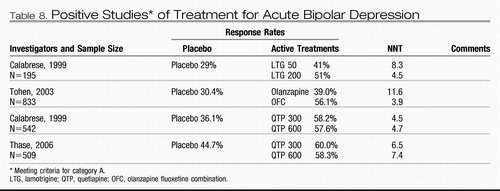

Bipolar depression

Meta-analysis supports the adjunctive use of standard antidepressants as treatment for bipolar depression (58); however, no standard antidepressants have shown efficacy in a category A study. Altshuler et al. (59) found that only about 15% of patients with bipolar depression for whom an anti-depressant was prescribed met the criteria for treatment response. Category A evidence supports the use of lamotrigine (60), olanzapine (61), quetiapine (62), and the combination of olanzapine and fluoxetine as treatment for acute bipolar depression (61).

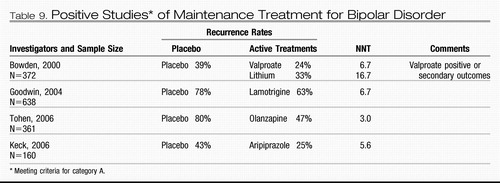

Maintenance treatment

Category A studies establishing the efficacy of lithium, lamotrigine (63–65), olanzapine (66–68), and aripiprazole (69)for preventing recurrence of acute episodes all included randomly assigned patients who had experienced a remission of acute-phase symptoms during treatment with the study medication before randomization. This methodological issue has important clinical implications. The data from these successful maintenance studies cannot support the practice of switching from acute-phase treatments to a new maintenance treatment after resolution of an acute episode. Instead the data support continued treatment with these agents if they were part of a successful acute-phase regimen.

Questions and controversy

Controversy about bipolar disorders stems from the obscure nature of bipolar disorder itself and the unmet needs of many patients. Whether bipolar disorders are defined too narrowly or too broadly will only become clear when the pathophysiology processes underlying bipolar disorders are known. Research studies focused on the episodes of depression or mood elevation are of limited utility in helping us to grasp the nature of this lifelong multidimensional illness. Understanding the nature of heart disease led to treatments that prevent rather than treat myocardial infarction. Similarly, understanding the causes of bipolar disorder will lead to development of interventions that ameliorate the disease process itself rather than simply offer treatment for the abnormal mood episodes. It is possible that interventions that target signal transduction pathways, reduce stress, stabilize circadian rhythms, manage negative expressed emotion, or improve resilience will prevent or alter the course of bipolar disorder.

Treatment of bipolar depression remains the area of greatest unmet need, and the role of standard antidepressants may be the most controversial issue for clinicians treating bipolar disorder. The available evidence offers little support for the use of standard antidepressants, and it does not offer strong reasons to believe that standard antidepressants are generally harmful. Currently, venlafaxine is the only standard antidepressant for which a statistically significant increase in the risk of treatment-emergent affective switch has been demonstrated in a high-quality double-blind study (70). It seems likely that questions about standard antidepressant treatment will persist until robustly effective treatments for bipolar depression become available.

Recommendations from the author

For all its complexity, bipolar disorder is a rewarding condition to manage. The increased quantity of high-quality clinical trial data makes it possible to provide many patients a menu of reasonable choices that begins with category A evidence-based options. I believe the key to success is to individualize clinical management by understanding the patient and his or her goals as well as the pertinent clinical study data. Systematic diagnostic assessment and integration of ongoing measurement can improve outcomes through the recognition of comorbid conditions and iterative feedback to the clinical decision-making process. The goal of maximizing each patient’s quality of life requires long-term collaboration that draws on the clinician’s skill as a teacher and negotiator.

|

Table 1. Summary of Primary Mood Disorders and Subtypes

|

Table 2. Summary of DSM-IV Criteria for Mood Episodes

|

Table 3. Summary of DSM-IV Course Specifiers

|

Table 4. Diagnostic Challenges

|

Table 5. Initial Assessment Strategies

|

Table 6. Positive Studies* of Monotherapy Treatment for Acute Mania

|

Table 7. Positive Studies* of Adjunctive Treatment for Acute Mania

|

Table 8. Positive Studies* of Treatment for Acute Bipolar Depression

|

Table 9. Positive Studies* of Maintenance Treatment for Bipolar Disorder

Figure 1. Schema for Syatematic Individualized Care

1 Angst J, Gamma A, Lewinsohn P: The evolving epidemiology of bipolar disorder. World Psychiatry 2002; 1:146–148Google Scholar

2 Judd LL, Akiskal HS: The prevalence and disability of bipolar spectrum disorders in the US population: re-analysis of the ECA database taking into account subthreshold cases. J Affect Disord 2003; 73:123–131Crossref, Google Scholar

3 Kessler RC, Akiskal HS, Ames M, Birnbaum H, Greenberg P, A RM, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Simon GE, Wang PS: Prevalence and effects of mood disorders on work performance in a nationally representative sample of U.S. workers. Am J Psychiatry 2006; 163:1561–1568Crossref, Google Scholar

4 Perlis RH, Miyahara S, Marangell LB, Wisniewski SR, Ostacher M, DelBello MP, Bowden CL, Sachs GS, Nierenberg AA: Long-term implications of early onset in bipolar disorder: data from the first 1000 participants in the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD). Biol Psychiatry 2004; 55:875–881Crossref, Google Scholar

5 Leboyer M, Henry C, Paillere-Martinot ML, Bellivier F: Age at onset in bipolar affective disorders: a review. Bipolar Disord 2005; 7:111–118Crossref, Google Scholar

6 Simon GE: Social and economic burden of mood disorders. Biol Psychiatry 2003; 54:208–215Crossref, Google Scholar

7 Simon NM, Otto MW, Wisniewski SR, Fossey M, Sagduyu K, Frank E, Sachs GS, Nierenberg AA, Thase ME, Pollack MH: Anxiety disorder comorbidity in bipolar disorder patients: data from the first 500 participants in the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD). Am J Psychiatry 2004; 161:2222–2229Crossref, Google Scholar

8 Summers M, Papadopoulou K, Bruno S, Cipolotti L, Ron MA: Bipolar I and bipolar II disorder: cognition and emotion processing. Psychol Med. 2006; 36:1799–1809Crossref, Google Scholar

9 Chengappa KN, Levine J, Gershon S, Kupfer DJ: Lifetime prevalence of substance or alcohol abuse and dependence among subjects with bipolar I and II disorders in a voluntary registry. Bipolar Disord 2000; 2(3 pt 1):191–195Crossref, Google Scholar

10 Goldberg JF, Garno JL, Leon AC, Kocsis JH, Portera L: A history of substance abuse complicates remission from acute mania in bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 1999; 60:733–740Crossref, Google Scholar

11 Brady KT, Lydiard RB: Bipolar affective disorder and substance abuse. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1992; 12(1 suppl):17S–22SCrossref, Google Scholar

12 Biederman J, Faraone SV, Wozniak J, Monuteaux MC: Parsing the association between bipolar, conduct, and substance use disorders: a familial risk analysis. Biol Psychiatry 2000; 48:1037–1044Crossref, Google Scholar

13 Winokur G, Turvey C, Akiskal H, Coryell W, Solomon D, Leon A, Mueller T, Endicott J, Maser J, Keller M: Alcoholism and drug abuse in three groups— bipolar I, unipolars and their acquaintances. J Affect Disord 1998; 50:81–89Crossref, Google Scholar

14 Venn HR, Gray JM, Montagne B, Murray LK, Michael Burt D, Frigerio E, Perrett DI, Young AH: Perception of facial expressions of emotion in bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord 2004; 6:286–293Crossref, Google Scholar

15 Clark L, Kempton MJ, Scarna A, Grasby PM, Goodwin GM: Sustained attention-deficit confirmed in euthymic bipolar disorder but not in first-degree relatives of bipolar patients or euthymic unipolar depression. Biol Psychiatry 2005; 57:183–187Crossref, Google Scholar

16 Robinson LJ, Thompson JM, Gallagher P, Goswami U, Young AH, Ferrier IN, Moore PB: A meta-analysis of cognitive deficits in euthymic patients with bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord 2006; 93:105–115Crossref, Google Scholar

17 Evans DL, Charney DS, Lewis L, Golden RN, Gorman JM, Krishnan KR, Nemeroff CB, Bremner JD, Carney RM, Coyne JC, Delong MR, Frasure-Smith N, Glassman AH, Gold PW, Grant I, Gwyther L, Ironson G, Johnson RL, Kanner AM, Katon WJ, Kaufmann PG, Keefe FJ, Ketter T, Laughren TP, Leserman J, Lyketsos CG, McDonald WM, McEwen BS, Miller AH, Musselman D, O’Connor C, Petitto JM, Pollock BG, Robinson RG, Roose SP, Rowland J, Sheline Y, Sheps DS, Simon G, Spiegel D, Stunkard A, Sunderland T, Tibbits P Jr, Valvo WJ: Mood disorders in the medically ill: scientific review and recommendations. Biol Psychiatry 2005; 58:175–189Crossref, Google Scholar

18 McIntyre RS, Konarski JZ, Soczynska JK, Wilkins K, Panjwani G, Bouffard B, Bottas A, Kennedy SH: Medical comorbidity in bipolar disorder: implications for functional outcomes and health service utilization. Psychiatr Serv 2006; 57:1140–1144Crossref, Google Scholar

19 Newcomer JW: Medical risk in patients with bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry 2006; 67(suppl 9):25–30; discussion 36–42Google Scholar

20 Wang PW, Sachs GS, Zarate CA, Marangell LB, Calabrese JR, Goldberg JF, Sagduyu K, Miyahara S, Ketter TA: Overweight and obesity in bipolar disorders. J Psychiatr Res. 2006; 40:762–764Crossref, Google Scholar

21 Arnold LM, Hudson JI, Keck PE, Auchenbach MB, Javaras KN, Hess EV: Comorbidity of fibromyalgia and psychiatric disorders. J Clin Psychiatry 2006; 67:1219–1225Crossref, Google Scholar

22 Hamelsky SW, Lipton RB: Psychiatric comorbidity of migraine. Headache 2006; 46:1327–1333Crossref, Google Scholar

23 McKenna MT, Michaud CM, Murray CJ, Marks JS: Assessing the burden of disease in the United States using disability-adjusted life years. Am J Prev Med 2005; 28:415–423Crossref, Google Scholar

24 Ustun TB, Ayuso-Mateos JL, Chatterji S, Mathers C, Murray CJ: Global burden of depressive disorders in the year 2000. Br J Psychiatry 2004; 184:386–392Crossref, Google Scholar

25 Murray CJ, Lopez AD, Jamison DT: The global burden of disease in 1990: summary results, sensitivity analysis and future directions. Bull World Health Organ 1994; 72:495–509Google Scholar

26 Osby U, Brandt L, Correia N, Ekbom A, Sparen P: Excess mortality in bipolar and unipolar disorder in Sweden. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2001; 58:844–850Crossref, Google Scholar

27 Angst F, Stassen HH, Clayton PJ, Angst J: Mortality of patients with mood disorders: follow-up over 34–38 years. J Affect Disord 2002; 68:167–181Crossref, Google Scholar

28 Kraepelin E: Manic-Depressive Insanity and Paranoia. Edinburgh, E & S Livingstone, 1921Google Scholar

29 Leonhard K: Uber monopolare und bipolare endogene Psychosen. Nervenarzt 1968; 39:104–106Google Scholar

30 Angst J, Marneros A: Bipolarity from ancient to modern times: conception, birth and rebirth. J Affect Disord 2001; 67:3–19Crossref, Google Scholar

31 Winokur G, Clayton P: Family history studies. I. Two types of affective disorders separated according to genetic and clinical factors. Recent Adv Biol Psychiatry 1966; 9:35–50Google Scholar

32 American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1994Google Scholar

33 Lish JD, Dime-Meenan S, Whybrow PC, Price RA, Hirschfeld RM: The National Depressive and Manic-Depressive Association (DMDA) survey of bipolar members. J Affect Disord 1994; 31:281–294Crossref, Google Scholar

34 Hirschfeld RM, Lewis L, Vornik LA: Perceptions and impact of bipolar disorder: how far have we really come? Results of the National Depressive and Manic-Depressive Association 2000 survey of individuals with bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2003; 64:161–174Crossref, Google Scholar

35 Judd LL, Akiskal HS, Schettler PJ, Coryell W, Maser J, Rice JA, Solomon DA, Keller MB: The comparative clinical phenotype and long term longitudinal episode course of bipolar I and II: a clinical spectrum or distinct disorders? J Affect Disord 2003; 73:19–32Crossref, Google Scholar

36 Hirschfeld RM, Cass AR, Holt DC, Carlson CA: Screening for bipolar disorder in patients treated for depression in a family medicine clinic. J. Am Board Fam Pract 2005; 18:233–239Crossref, Google Scholar

37 Sachs GS: Strategies for improving treatment of bipolar disorder: integration of measurement and management. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl 2004:7–17Google Scholar

38 Sachs GS, Thase ME, Otto MW, Bauer M, Miklowitz D, Wisniewski SR, Lavori P, Lebowitz B, Rudorfer M, Frank E, Nierenberg AA, Fava M, Bowden C, Ketter T, Marangell L, Calabrese J, Kupfer D, Rosenbaum JF: Rationale, design, and methods of the systematic treatment enhancement program for bipolar disorder (STEP-BD). Biol Psychiatry 2003; 53:1028–1042Crossref, Google Scholar

39 Fisher R, Uri W, Patton B: Getting To Yes: Negotiating Agreement Without Giving In. Boston, Houghton Mifflin, 1991Google Scholar

40 Dowie J: The ‘number needed to treat’ and the ‘adjusted NNT’ in health care decision-making. J Health Serv Res Policy 1998; 3:44–49Crossref, Google Scholar

41 Sinclair JC: Weighing risks and benefits in treating the individual patient. Clin Perinatol 2003; 30:251–268Crossref, Google Scholar

42 Faraone SV: Understanding the effect size of ADHD medications: implications for clinical care, in Medscape Psychiatry & Mental Health, New York, Medscape, 2003 http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/461543Google Scholar

43 Prien RF, Caffey EM Jr, Klett CJ: Comparison of lithium carbonate and chlorpromazine in the treatment of mania: report of the Veterans Administration and National Institute of Mental Health Collaborative Study Group. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1972; 26:146–153Crossref, Google Scholar

44 Sachs GS, Grossman F, Ghaemi SN, Okamoto A, Bowden CL: Combination of a mood stabilizer with risperidone or haloperidol for treatment of acute mania: a double-blind, placebo-controlled comparison of efficacy and safety. Am J Psychiatry 2002; 159:1146–1154Crossref, Google Scholar

45 Zajecka JM, Weisler R, Sachs G, Swann AC, Wozniak P, Sommerville KW: A comparison of the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of divalproex sodium and olanzapine in the treatment of bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2002; 63:1148–1155Crossref, Google Scholar

46 Tohen M, Goldberg JF, Gonzalez-Pinto Arrillaga AM, Azorin JM, Vieta E, Hardy-Bayle MC, Lawson WB, Emsley RA, Zhang F, Baker RW, Risser RC, Namjoshi MA, Evans AR, Breier A: A 12-week, double-blind comparison of olanzapine vs haloperidol in the treatment of acute mania. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2003; 60:1218–1226Crossref, Google Scholar

47 Vieta E, Bourin M, Sanchez R, Marcus R, Stock E, McQuade R, Carson W, Abou-Gharbia N, Swanink R, Iwamoto T: Effectiveness of aripiprazole v. haloperidol in acute bipolar mania: double-blind, randomised, comparative 12-week trial. Br J Psychiatry 2005; 187:235–242Crossref, Google Scholar

48 Bowden CL, Grunze H, Mullen J, Brecher M, Paulsson B, Jones M, Vagero M, Svensson K: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled efficacy and safety study of quetiapine or lithium as monotherapy for mania in bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2005; 66:111–121Crossref, Google Scholar

49 McIntyre RS, Brecher M, Paulsson B, Huizar K, Mullen J: Quetiapine or haloperidol as monotherapy for bipolar mania—a 12-week, double-blind, randomised, parallel-group, placebo-controlled trial. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 2005; 15:573–585Crossref, Google Scholar

50 Tohen M, Baker RW, Altshuler LL, Zarate CA, Suppes T, Ketter TA, Milton DR, Risser R, Gilmore JA, Breier A, Tollefson GA: Olanzapine versus divalproex in the treatment of acute mania. Am J Psychiatry 2002; 159:1011–1017Crossref, Google Scholar

51 Khanna S, Vieta E, Lyons B, Grossman F, Eerdekens M, Kramer M: Risperidone in the treatment of acute mania: double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Br J Psychiatry 2005; 187:229–234Crossref, Google Scholar

52 Hirschfeld RM, Keck PE Jr, Kramer M, Karcher K, Canuso C, EerdekensM, Grossman F: Rapid antimanic effect of risperidone monotherapy: a 3-week multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry 2004; 161:1057–1065Crossref, Google Scholar

53 Ketter T, Wang PW, Nowakowska C, Marsh WK, Bonner J: Treatment of acute mania in bipolar disorder, in Advances in the Treatment of Bipolar Disorder, vol 24, no 3. Edited by Ketter T. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Publishing, 2005Google Scholar

54 Perlis RH, Welge JA, Vornik LA, Hirschfeld RM, Keck PE Jr: Atypical antipsychotics in the treatment of mania: a meta-analysis of randomized, placebo-controlled trials. J Clin Psychiatry 2006; 67:509–516Crossref, Google Scholar

55 Muller-Oerlinghausen B, Retzow A, Henn FA, Giedke H, Walden J: Valproate as an adjunct to neuroleptic medication for the treatment of acute episodes of mania: a prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter study. European Valproate Mania Study Group. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2000; 20:195–203Crossref, Google Scholar

56 Post RM, Ketter TA, Pazzaglia PJ, Denicoff K, George MS, Callahan A, Leverich G, Frye M: Rational polypharmacy in the bipolar affective disorders. Epilepsy Res Suppl 1996; 11:153–180Google Scholar

57 Freeman MP, Stoll AL: Mood stabilizer combinations: a review of safety and efficacy. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:12–21Crossref, Google Scholar

58 Gijsman HJ, Geddes JR, Rendell JM, Nolen WA, Goodwin GM: Antidepressants for bipolar depression: a systematic review of randomized, controlled trials. Am J Psychiatry 2004; 161:1537–1547Crossref, Google Scholar

59 Altshuler L, Suppes T, Black D, Nolen WA, Keck PE Jr, Frye MA, McElroy S, Kupka R, Grunze H, Walden J, Leverich G, Denicoff K, Luckenbaugh D, Post R: Impact of antidepressant discontinuation after acute bipolar depression remission on rates of depressive relapse at 1-year follow-up. Am J Psychiatry 2003; 160:1252–1262Crossref, Google Scholar

60 Calabrese JR, Bowden CL, Sachs GS, Ascher JA, Monaghan E, Rudd GD: A double-blind placebo-controlled study of lamotrigine monotherapy in outpatients with bipolar I depression. Lamictal 602 Study Group. J Clin Psychiatry 1999; 60:79–88Crossref, Google Scholar

61 Tohen M, Vieta E, Calabrese J, Ketter TA, Sachs G, Bowden C, Mitchell PB, Centorrino F, Risser R, Baker RW, Evans AR, Beymer K, Dube S, Tollefson GD, Breier A: Efficacy of olanzapine and olanzapine-fluoxetine combination in the treatment of bipolar I depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2003; 60:1079–1088Crossref, Google Scholar

62 Calabrese JR, Keck PE Jr, Macfadden W, Minkwitz M, Ketter TA, Weisler RH, Cutler AJ, McCoy R, Wilson E, Mullen J: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of quetiapine in the treatment of bipolar I or II depression. Am J Psychiatry 2005; 162:1351–1360Crossref, Google Scholar

63 Bowden CL, Calabrese JR, Sachs G, Yatham LN, Asghar SA, Hompland M, Montgomery P, Earl N, Smoot TM, DeVeaugh-Geiss J: A placebo-controlled 18-month trial of lamotrigine and lithium maintenance treatment in recently manic or hypomanic patients with bipolar I disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2003; 60:392–400Crossref, Google Scholar

64 Calabrese JR, Bowden CL, Sachs G, Yatham LN, Behnke K, Mehtonen OP, Montgomery P, Ascher J, Paska W, Earl N, DeVeaugh-Geiss J: A placebo-controlled 18-month trial of lamotrigine and lithium maintenance treatment in recently depressed patients with bipolar I disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2003; 64:1013–1024Crossref, Google Scholar

65 Goodwin GM, Bowden CL, Calabrese JR, Grunze H, Kasper S, White R, Greene P, Leadbetter R: A pooled analysis of 2 placebo-controlled 18-month trials of lamotrigine and lithium maintenance in bipolar I disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2004; 65:432–441Crossref, Google Scholar

66 Tohen M, Greil W, Calabrese JR, Sachs GS, Yatham LN, Oerlinghausen BM, Koukopoulos A, Cassano GB, Grunze H, Licht RW, Dell’Osso L, Evans AR, Risser R, Baker RW, Crane H, Dossenbach MR, Bowden CL: Olanzapine versus lithium in the maintenance treatment of bipolar disorder: a 12-month, randomized, double-blind, controlled clinical trial. Am J Psychiatry 2005; 162:1281–1290Crossref, Google Scholar

67 Tohen M, Ketter TA, Zarate CA, Suppes T, Frye M, Altshuler L, Zajecka J, Schuh LM, Risser RC, Brown E, Baker RW: Olanzapine versus divalproex sodium for the treatment of acute mania and maintenance of remission: a 47-week study. Am J Psychiatry 2003; 160:1263–1271Crossref, Google Scholar

68 Tohen M, Calabrese JR, Sachs GS, Banov MD, Detke HC, Risser R, Baker RW, Chou JC, Bowden CL: Randomized, placebo-controlled trial of olanzapine as maintenance therapy in patients with bipolar I disorder responding to acute treatment with olanzapine. Am J Psychiatry 2006; 163:247–256Crossref, Google Scholar

69 Keck PE Jr, Calabrese JR, McQuade RD, Carson WH, Carlson BX, Rollin LM, Marcus RN, Sanchez R: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled 26-week trial of aripiprazole in recently manic patients with bipolar I disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2006; 67:626–637Crossref, Google Scholar

70 Post RM, Altshuler LL, Leverich GS, Frye MA, Nolen WA, Kupka RW, Suppes T, McElroy S, Keck PE, Denicoff KD, Grunze H, Walden J, Kitchen CM, Mintz J: Mood switch in bipolar depression: comparison of adjunctive venlafaxine, bupropion and sertraline. Br J Psychiatry 2006; 189:124–131Crossref, Google Scholar