Australian and New Zealand Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Treatment of Anorexia Nervosa

Abstract

Background: The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists is coordinating the development of clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) in psychiatry, funded under the National Mental Health Strategy (Australia) and the New Zealand Ministry of Health. This CPG covers anorexia nervosa (AN). Method: The CGP team consulted with scientists, clinicians, carers and consumer groups in meetings of over 200 participants and conducted a systematic review of meta-analyses, randomized controlled trials and other studies. Treatment recommendations: It is extremely difficult to draw general conclusions about the efficacy of specific treatment options for AN. There are few controlled clinical trials and their quality is generally poor. These guidelines necessarily rely largely upon expert opinion and uncontrolled trials. A multidimensional approach is recommended. Medical manifestations of the illness need to be addressed and any physical harm halted and reversed. Weight restoration is essential in treatment, but insufficient evidence is available for any single approach. A lenient approach is likely to be more acceptable to patients than a punitive one and less likely to impair self-esteem. Dealing with the psychiatric problems is not simple and much controversy remains. For patients with less severe AN who do not require in-patient treatment, out-patient or day-patient treatment may be suitable, but this decision will depend on availability of such services. Family therapy is a valuable part of treatment, particularly for children and adolescents, but no particular approach emerges as superior to any other. Dietary advice should be included in all treatment programs. Cognitive behaviour therapy or other psychotherapies are likely to be helpful. Antidepressants have a role in patients with depressive symptoms and olanzapine may be useful in attenuating hyperactivity.

Definitions and main features

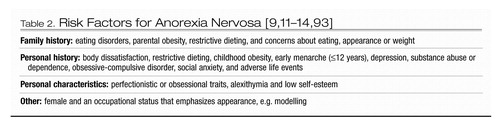

Anorexia nervosa (AN) is a serious and potentially fatal mental illness. Its key feature is deliberate loss of weight through strict dieting and avoidance of foods perceived to be fattening. Food intake is restricted, despite severe hunger. Perception of physiological signals of hunger becomes confused, including when one is satiated. Excessive exercise and uncontrolled hyperactivity are common, in addition to extreme weight control behaviours, including purging through means of self-induced vomiting (e.g. using an emetic), eating large quantities of fibrous foods and consuming laxatives, appetite suppressants or diuretics [1,2] (Table 1).

Diagnostic criteria of the World Health Organization’s (WHO) International Classification of Disease (ICD) 10th edition [3], are cited here (in preference the DSM-IV [4]) as we thought them more useful and less likely to be changed in the near future. Bulimia nervosa (BN), another major eating disorder, is beyond our scope and excellently reviewed by Wilson and Fairburn [5]. ‘Eating disorder not otherwise specified’ (EDNOS) or ‘atypical eating disorder’ is a third category where the illness may be evolving, resolving, secondary to another psychiatric illness (e.g. depression, anxiety, hypochondriasis or schizophrenia) or a binge-eating syndrome [6]. These guidelines also include atypical AN patients [3] namely those who fail to meet criteria, are in the initial phase of their illness or are partially recovered.

Epidemiology and risk factors

Anorexia nervosa occurs in 0.2–0.5% of women, is rare in men (< 10% of cases) [1,7,8] and usually begins in adolescence or young adulthood [9]. In developed societies, a slight bias toward higher socio-economic status is common [2]. In children born or reared in Australia and New Zealand, AN crosses diverse cultures although there is scanty information regarding indigenous peoples [9]. Age of onset is broadening, with more prepubertal children and older adults affected [10].

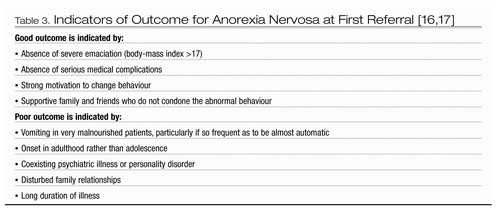

Although dieting is a common antecedent behaviour, few dieters develop AN [11–13]. Familial association is strong. Specific genes, such as one relating to noradrenalin transmission, are currently subject to study [14]. Risk factors are listed in Table 2.

Course and outcome

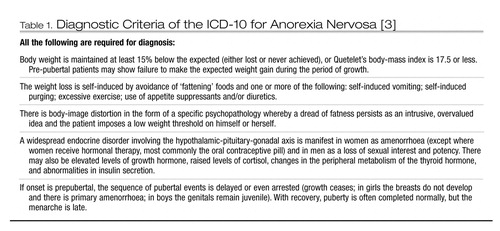

Like other serious, low prevalence conditions, such as schizophrenia, AN has a profound effect on health and quality of life given its chronic, severe course [15]. Although 70% of patients regain weight within 6 months of onset of treatment, 15–25% of these relapse, usually within 2 years. A proportion of people with AN die from medical complications or suicide. Follow-up studies suggest that under one-half have a good outcome (normal weight and eating and return of menses), a third intermediate and the remainder poor [16]. A one-in-five mortality rate at two decades follow-up indicates that patients chronically preoccupied with weight develop grave physical conditions [17]. Indeed, the estimated mortality rate is 12 times that of similar aged women in the community and double that of women suffering other psychiatric disorders. Risk of suicide is high, being 1.5 times higher than for people with major depression [18].

Prompt recognition and treatment is likely to improve the prognosis, but recovery is yet possible, even after many years of illness. It is never too late to apply vigorous treatment. People with less severe AN, who are treated as outpatients, have a better outcome, although long-term support is necessary in order to prevent recurrence. Those who ‘recover’ from AN often retain certain features of atypical eating disorder (EDNOS). Indicators of outcome are listed in Table 3.

Method

Key features in developing this CPG were: (i) a systematic review of the literature; (ii) multidisciplinary and internationally representative workshops (the first was attended by over 200 participants and included consultation with representative consumer, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander and Maori groups); and (iii) drafting of consensual views broadly applying the Delphi technique [19]. The Delphi technique typically takes place via several rounds of a mailed survey. At its simplest, Delphi acts by asking a question (or several) of a panel and collating and summarizing the replies. The summary is sent out to start the next cycle. A panel member may change his/her estimate in the direction of an emerging consensus. Alternatively, he/she may leave his/her original estimate intact and provide information justifying it. At the heart of the technique is a cyclic process and a way of using disagreement as a trigger for deeper analysis. In most Delphi processes the level of consensus increases from round to round [20].

A search was conducted for all trials of any form of therapy for AN and/or EDNOS of AN type. Quality analyses (and grading) of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) were made by two reviewers who applied the 23-item criteria from the Cochrane Collaboration Depression and Anxiety Group (CCDAN, see http://web1.iop.kcl.ac.uk/IoP/ccdan/qrs.htm). There were no exclusion criteria for types of participants or interventions. The search strategy (1967 to August 2001, updated to November 2002 with help from CCDAN) comprised: hand-search of the International Journal of Eating Disorders since its first issue; MEDLINE since 1967; EXTRAMED; EMBASE; PsycLIT; Current Contents; Cochrane Collaboration Controlled Trials Register (CCCTR: The Cochrane Library, 1997 Internet version). Search terms used throughout were: ‘anorexia nervosa and (therapy or pharmacotherapy or cognitive behaviour therapy or trial* or treatment* or psychotherapy)’. Letters were also sent to 16 prominent investigators in the US, UK, Europe, NZ and Australia, requesting information on unpublished trials or those in progress.

The working party consulted with cultural advisors and the major content of this document has been reviewed and endorsed by the Maori Mental Health Manager; this process was facilitated by Dr Lois Surgenor.

General issues in treatment

Low prevalence and high morbidity present ethical problems in conducting RCTs. For example, it may not be ethical to randomise severely ill patients who present for treatment to a trial where they may be allocated to an unproven treatment. Some treatments, for example potassium replacement in hypokalaemia do not require an RCT. In addition, ‘insufficient evidence’ and ‘no evidence’ are not synonymous with ‘evidence of ineffectiveness’ and, in the absence of evidence, clinical consensus is legitimate.

The CPG Team agreed that while diagnosis and treatment are the preserve of psychiatry, a multidisciplinary team is indicated for optimal treatment of AN. The team ideally would include a specialist in physical medicine (e.g. a general practitioner, physician or paediatrician, depending on the patient’s age), a dietitian, nurses and other allied health specialists such as psychologists, occupational therapists and physiotherapists.

While prompt identification and treatment can prevent spiralling ill-health [21], this is often hampered by concentration of expertise in specialist centres. The severely ill patient often denies illness and/or refuses treatment and tension ensues between the patient’s autonomy versus need for treatment. As discussed by Goldner et al. [22] certain, usually life-threatening, circumstances may require involuntary treatment and/or breaches of confidentiality.

Management necessarily includes restoration of nutrition. The most humane and effective form is ‘supported meals’, in which a regular diet is instituted under supervision. Other options are operant conditioning programs, high energy food supplementation and/or naso-gastric feeding. Psychological support, an empathic therapeutic relationship and cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT) strategies are employed throughout treatment.

Many people can be treated as outpatients or day-patients [23–25]. Success depends on illness stage, complexity and severity, and on availability of family or other home-based supports, community practitioners with good expertise and back-up hospital treatment. Long-term treatment is usually necessary for chronic forms of the illness since ‘cure’ is rarely attained.

Primary prevention is problematic, but general mental health programs, directed at areas such as boosting the self-esteem of young people, show promise [26,27]. A systematic review of interventions for preventing eating disorders in children [28] revealed only eight studies that met inclusion criteria. Combined data from two programs, based on a media literacy and advocacy approach, indicated reduced acceptance of social ideals related to appearance at a 3–6-month follow-up. There was insufficient evidence to support the effect of the other programs.

Medical assessment and management

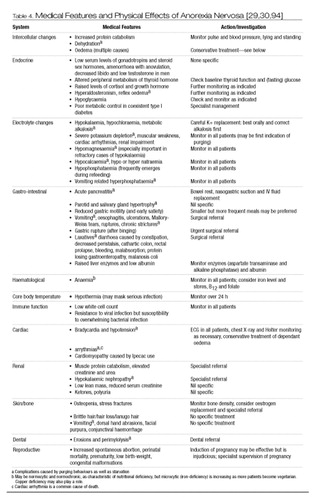

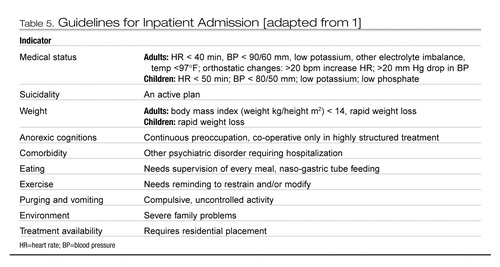

Medical features of AN are best regarded as manifestations rather than as complications of the illness (Table 4). As the course is often prolonged, the most severely ill are often in their early or mid-adulthood. Medical management is challenging, particularly if purging and/or the re-feeding syndrome complicate the starvation state. Weight loss must be curbed if not reversed and treatment offered for physical problems associated with starvation. Baseline and repeated assessments are essential. A minimum requirement is regular monitoring of vital signs, weight and dietary intake [29]. Acute medical decompensation calls for emergency inpatient treatment (Table 5).

Under-nutrition results from an energy-deficient diet and precedes specific nutrient deficiencies of, for example, thiamine [30]. Many medical features are mechanisms to limit the effects of energy deficit and correction is not necessarily indicated. For example, sick euthyroid syndrome should not be treated with thyroid replacement. The body gradually adapts to starvation in order to maintain normal function and blood electrolyte levels are therefore often normal.

Once metabolism is stimulated by re-feeding, the massive call for substances such as potassium and phosphates can be met only by drastically reducing blood levels, often with fatal consequences—the ‘re-feeding syndrome’. People with recent, rapid weight loss, minimal energy intake, high serum urea, and low phosphate, magnesium, potassium and glucose are at particular risk. Features of the syndrome include dyspnoea, generalized weakness, fatigue, peripheral oedema, seizures, coma, paraesthesia and visual and auditory hallucinations. Sudden death may occur. Treatment involves: bed-rest; correction of hydration status; multivitamin supplements; thiamine (e.g. 100 mg daily for 5 days); sodium phosphate (e.g. 550 mg, thrice daily, for 21 days); zinc gluconate (e.g. 100–200 mg daily for 2 months); and potassium chloride (e.g. 24 mEq thrice daily for 21 days). Food is introduced cautiously, starting with for example, 600–800 kcal per day and increasing by 300 kcal every third day. If the re-feeding syndrome occurs, nutrient intake is reduced or suspended [30].

During re-feeding, less restrictive behavioural approaches are likely to be as effective as strict regimens that are often perceived by the patient as punitive and demeaning [31,32]. Daily weighing draws undue attention to weight; twice-weekly is sufficient [33]. Psychotherapy, for example CBT, serves to correct erroneous beliefs about food intake and weight [34], bolsters motivation [35,36] and attentuates the typical ascetic, self-punitive and self-denying qualities from which the extreme weight-control behaviours derive [37]. Antidepressants are indicated for any concurrent depression. Olanzapine decreases hyperactivity and may reduce overvalued ideas about food, shape and weight [38].

Chronic AN leads to isolation (even reclusiveness), inability to work or study and impaired social relationships. The health professional acts as bridge between patient and family, explaining the nature and management of AN. In addition to rehabilitative strategies to improve interpersonal and adaptive function (e.g. encouraging involvement in a support group), associated medical and psychiatric conditions require continued monitoring and treatment [39].

Current evidence on treatment

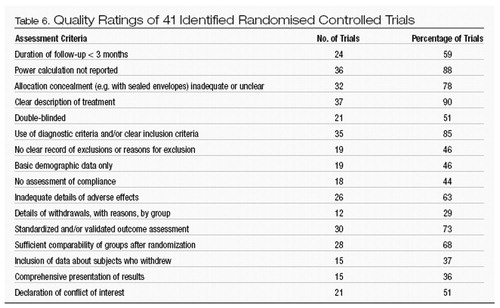

In our review, the CPG Team considered the question of where to treat, the efficacy of psychological and drug therapies and related treatment issues. We identified 47 RCTs, 41 with adequate data to grade quality. Their overall quality is poor, with inadequate sample sizes, unclear or inadequate concealment of allocation (e.g. not using sealed envelopes), failure to apply intention-to-treat analyses and patchy reporting of results. Details of the quality gradings are found in Table 6. In addition, there are limitations in generalizability of RCT findings to community and primary care settings, since most research has been conducted in specialist eating disorder units treating adults with severe illness.

Where to treat?

A systematic review [40] identified only one adequately conducted RCT [41,42] and a second unpublished one [43]. The review’s authors concluded that in patients severe enough to consider hospital-based treatment, but not extreme enough for this to be essential (e.g. to prevent death), outpatient treatment is as effective (perhaps more so) as inpatient treatment. The benefits of treatment in either setting appear to increase over time. Outpatient treatment is, however, considerably more cost-effective. Caveats of this review include the non-blinding of the single published trial [41,42] and imprecise cost-evaluation. Adherence was higher in outpatient groups. Two deaths occurred in the trial, an outpatient and an inpatient.

Evidence from case series [40] shows a wide range of mortality and benefits, preventing firm conclusions. This material is also likely to be biased as case-control and research audit suggest that those admitted have a lower weight than those not admitted. Finally, the authors noted that duration of hospital stay appears to be decreasing [40].

Guideline: For patients with AN which is not so severe as to require inpatient treatment (e.g. where the risk of death from suicide or physical effects is high), outpatient or day-patient treatment may be suitable, but this decision will depend on availability of appropriate services.

Psychological treatments

Family therapy

We have identified three RCTs of family therapy compared with other therapies. In one, behavioural family therapy [44–46] is more effective than individual therapy in leading to weight gain and resumption of menses in adolescents, but not in changing eating attitudes, depression or family conflict. In a study of adult patients, greater improvement in weight and psychosocial adjustment occurred at two-year follow-up [41,42] in both individual and family therapy groups compared to assessment alone. Poorer outcome was associated with low weight at baseline, non-compliance and self-induced vomiting. Family, focal psychoanalytic and cognitive analytic therapy were all superior to routine treatment (low contact outpatient individual therapy with psychiatric trainees) in a study of adult outpatients [47].

With regard to prevention of relapse, a 5-year follow-up of people who had received a year of family or individual supportive therapy after inpatient weight restoration at a specialist hospital [48,49] showed improvement in general, more marked if intervention was prompt (illness < 3 years duration) and age of onset < 18 years. Family therapy was most effective for a younger group. Patients with late onset AN benefited most from individual therapy.

With regard to ‘schools’ of family therapy, we identified three studies. A study of adolescents [50], seeing the patient and her parents and siblings for eight sessions or eight sessions of ‘family group psychoeducation’ (families were seen together in a class format versus separately) produced no significant differences in weight gain, eating disorder symptoms as measured on the drive for thinness, body dissatisfaction and bulimia sub-scales of the Eating Disorders Inventory, or general psychiatric symptoms. A RCT [51,52] detected no marked difference in outcome on a global measure of eating disorder or weight between conjoint family therapy and ‘separated’ family therapy (patients and parents were seen separately). Structural family therapy, with and without individual body awareness therapy (focusing on correcting the distorted body image), in 26 adolescent patients produced no differences in recovery rates between the two groups [53].

CBT and behaviour therapy (BT)

Cognitive behaviour therapy, BT (diary keeping and exposure) and ‘standard eclectic’ therapy have been compared in an outpatient study [54]. All groups improved, the only difference between them being greater compliance with CBT. In comparing CBT and dietary advice [55], anorexic and depressive symptoms and body mass index improved with CBT; all members of the dietary group dropped out! An inpatient (age of subjects not provided) RCT found that weight gain was not enhanced by BT (operant conditioning) [56].

Other forms of psychological therapy

A trial of outpatients with severe AN compared dietary advice with combined individual and family therapy. Patients in both conditions improved overall, with better weight gain in the dietary advice group and enhanced sexual and social adjustment in those receiving therapy [57]. In a comparison of an educational behavioural treatment and cognitive analytical therapy in adult outpatients, weight gain occurred in both groups, but recipients of the latter felt better subjectively [58]. In a very small investigation [59], encouraging but inconclusive results were seen for two dynamic therapies. Results of a trial of interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT) by Joyce et al. are not yet available.

Finally, a Cochrane review on efficacy of various forms of outpatient individual therapy for adults with AN could not draw any conclusions because of insufficient evidence [60].

Psychotherapy versus medication

No published RCTs were identified.

Guideline: The consensus is that family therapy is a valuable part of treatment, particularly in the case of children and adolescents, but no specific approach emerges as superior to any other. Dietary advice should be included in all treatment programs. CBT or other therapies are likely to be helpful.

Drug treatments: inpatient trials

Cisapride

In a placebo-controlled study, cisapride did not affect weight gain but patients’ appetites improved and they subjectively felt better on visual analogue scales of feeling ‘tense’, ‘bloated’, ‘fat’ and ‘hungry’. Cardiac side-effects (malignant arrythmias) limit its application in Australia to the treatment of gastroparalysis by specialist physicians [61].

Antidepressants

The only study of fluoxetine (up to 60 mg daily) found no effect on weight gain, anorexic, depressive or other psychiatric symptom severity [62]. In a placebo-controlled RCT of amitriptyline (115 mg daily) [63], the adolescent participants all fared poorly. Clomipramine (50 mg daily) increases food intake and improves weight maintenance over placebo [64,65].

Cyproheptadine

When cyproheptadine, a serotonin and histamine antagonist, was compared with amitriptyline and placebo, both treatment groups reached target weights an average 10 days earlier than placebo. (Patients were offered food and controlled the amount consumed and were required to meet minimal levels of weight gain to remain in the study [66,67]). Cyproheptadine, with vitamins, increased weight gain compared to placebo, but produced hypersomnia in 60% of participants (as well as stomatitis) [68]. Three other studies [69–72] offer limited support for a role for cyproheptadine.

Zinc

Zinc supplements (100 mg daily of zinc gluconate) enhanced weight gain in an RCT of adult patients [73] and was further supported in an open trial [74].

Antipsychotics

In a double-blind crossover study of young adults on a re-feeding program, sulpiride produced greater weight gain than placebo [75]. A placebo-controlled RCT [76] of young adults on a behavioural program suggests that pimozide may enhance weight gain.

Lithium

Weight gain with minimal adverse effects has been found in a single placebo controlled trial of lithium. The mean plasma level was 1.0 ± 0.1 mEq/l [77].

Drug treatments: outpatient trials

Naltrexone reduces binge-eating and purging behaviours [78]. Cisapride improved weight gain in a tiny trial [79]. In a double-blind trial of fluoxetine (40 mg daily), the active drug produced superior weight gain and improvement in anorexic, depressive, anxiety, obsessive and compulsive symptoms compared to placebo. In addition, the dropout rate was much higher in the placebo group [80].

When a small number of outpatients, all receiving psychological therapies, were randomised to either nortriptyline (75 mg daily) or fluoxetine (60 mg daily), weight gain and anxiety reduction were greater in the tricyclic group. A similar trial with binge-eating, purging patients [81] of fluoxetine (60 mg daily) and amineptine (a tricyclic, 300 mg daily) showed the SSRI superior in terms of weight gain.

Guideline: Evidence for antidepressant and antipsychotic efficacy is insufficient. However, the consensus is that antidepressants have a role in patients with marked depressive symptoms and olanzapine helps to attenuate hyper-activity. Cyproheptadine, zinc supplements, lithium and naltrexone warrant further study.

Related treatment issues

Naso-gastric versus ‘ordinary’ food in weight restoration

Only case reports and one qualitative case series review of adolescents [82] have been located. The latter outlines clinical guidelines in the application of feeding and recommends that naso-gastric feeding be introduced with the patient’s collaboration.

Guideline: Weight restoration is essential in treatment but evidence is lacking to recommend a specific approach.

Discharge at normal versus below normal weight

Although no RCTs were found, two studies [83,84] suggest that discharge at normal weight improves outcome. In the first [83] those who left hospital while still severely underweight had higher rates of re-admission.

Guideline: A consensus prevails that, particularly where after-care may be inadequate or unavailable, patients should achieve close to normal weight as an inpatient.

Lenient versus stricter programs

Conclusive findings are lacking. One RCT [85] found modest improvement in self-reported quality of life when a specialist-graded exercise program (following inpatient care) was compared with standard treatment. When a lenient inpatient program was compared with strict operant conditioning, no differences in weight gain were detected [86].

Guideline: A lenient approach is likely to be more acceptable to patients than a punitive one and less likely to impair self-esteem.

Specialist versus non-specialist programs

One level III [19] long-term study [87] has found higher mortality rates in non-specialist compared to specialist units. However, in an Australian prospective study [88], many patients improved without specialist input.

Guideline: Consensus and limited evidence provide some support for the value of specialist care, but further research is needed.

Osteoporosis

A placebo-RCT [89] of human insulin-like growth factor I found increased bone formation in the active treatment, but the trial was brief. In a longer but non-blinded trial of oestrogen (with progestin) in amenorrhoeic women, only those with low body-weight benefited [90]. A non-placebo RCT of three doses of oral dehydroepiandrosterone [91] in young women showed restored hormonal levels were achieved with 50 mg daily; bone resorption diminished, bone formation increased but mineral density was unchanged. Half the women resumed menstruation.

Guideline: Assessment of bone density should be routine. Evidence is lacking to recommend a specific approach to treat osteopaenia. Specialist referral is recommended.

Conclusions

It is difficult to draw conclusions about the efficacy of specific treatments in AN. Controlled trials are few and their quality poor [92]. While ethical and practical challenges are considerable, much more research is required. These guidelines necessarily rely on expert opinion and uncontrolled trials.

A multidimensional approach is recommended. Medical manifestations of the illness need to be addressed. Weight restoration in treatment is essential but evidence is unavailable to propose any specific approach. A lenient regimen is likely to be better tolerated by patients than a punitive one and also less likely to affect self-esteem.

Dealing with the psychiatric aspects of AN is complex with persistence of much controversy. For patients whose condition is not so severe as to require hospitalization, outpatient or day-patient treatment may be suitable, but this heavily depends on availability of appropriate services. Family therapy is a valuable part of treatment, particularly in children and adolescents, but no specific approach is superior to any other. Dietary advice should be a feature of all programs. Cognitive behaviour therapy or other psychotherapies are likely to help. Antidepressants play a role in patients with depressive symptoms and olanzapine in attenuating hyperactivity.

|

Table 1. Diagnostic Criteria of the ICD-10 for Anorexia Nervosa [3]

Table 3. Indicators of Outcome for Anorexia Nervosa at First Referral [16,17]

Table 4. Medical Features and Physical Effects of Anorexia Nervosa [29,30,94]

|

Table 5. Guidelines for Inpatient Admission [adapted from 1]

|

Table 6. Quality Ratings of 41 Identified Randomised Controlled Trials

1 American Psychiatric Association. Practice guidelines for the treatment of eating disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry 2000; 157Suppl:1–39.Crossref, Google Scholar

2 Beumont PJV. Clinical presentation of anorexia and bulimia nervosa. In: Brownell KD, Fairburn CG, eds. Eating disorders and obesity: a comprehensive handbook 2nd edn. New York: Guilford, 2002.Google Scholar

3 World Health Organisation. ICD-10: classification of mental and behavioural disorders. Geneva: World Health Organisation, 1992.Google Scholar

4 American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistic manual of mental disorders (DSM-IV), 4th edn. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, 1994.Google Scholar

5 Wilson GT, Fairburn CG. Treatments for eating disorders. In: Nathan PE, Gorman JM, eds. A guide to treatments that work. New York: Oxford University Press, 1998; 501–529.Google Scholar

6 Fairburn CG, Walsh BI. ‘Atypical’ eating disorders (EDNOS). In: Fairburn CG, Brownell KD, eds. Eating disorders and obesity: A comprehensive textbook 2nd edn. New York: Guilford, 2002; 171–177.Google Scholar

7 Beumont PJV, Beardwood CJ, Russell GFM. The occurrence of the syndrome of anorexia nervosa in male subjects. Psychological Medicine 1972; 2:216–231.Crossref, Google Scholar

8 Touyz SW, Kopec-Schrader EM, Beumont PJV. Anorexia nervosa in males: a report of 12 cases. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 1993; 27:512–517.Crossref, Google Scholar

9 Beumont PJV, Abraham SF, Argall WJ, George GCW, Glaun DE. The onset of anorexia nervosa. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 1978; 12:145–149.Crossref, Google Scholar

10 Lask B, Bryant-Waugh R. Childhood onset anorexia nervosa and related eating disorders. Howe: Lawrence Erlbaum, 1993.Google Scholar

11 Huon G. Dieting and binge eating, and some of their correlates among secondary school girls. In: Acting on Australia’s weight. Canberra: National Health and Medical Research Council, 1994; 146.Google Scholar

12 Huon GF, Walton C. Initiation of dieting among adolescent females. International Journal of Eating Disorders 2000; 28:226–230.Crossref, Google Scholar

13 Huon GF, Gunewardene A, Hayne A et al. Empirical support for a model of dieting: findings from structural equations modeling. International Journal of Eating Disorders 2002; 31:210–219.Crossref, Google Scholar

14 Urwin RE, Bennett SB, Wilcken B et al. Anorexia nervosa (restrictive subtype) is associated with a polymorphism in the novel norepinephrine transporter gene promoter polymorphic region. Molecular Psychiatry 2002; 6:652–657.Crossref, Google Scholar

15 Mathers C, Vos T, Stevenson C. Burden of disease and injuries in Australia. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 1999.Google Scholar

16 Steinhausen H-C. The outcome of anorexia nervosa in the twentieth century. American Journal of Psychiatry 2002; 159:1284–1293.Crossref, Google Scholar

17 Theander S. Chronicity in anorexia nervosa. In: Herzog W, Deter H-C, Vandereycken WV, eds. The course of eating disorders. Berlin: Springer, 1992; 214–227.Google Scholar

18 Harris EC, Barraclough B. Excess mortality of mental disorder. British Journal of Psychiatry 1998; 173:11–53.Crossref, Google Scholar

19 National Health and Medical Research Council A guide to the development, implementation and evaluation of clinical practice guidelines. Handbook series on preparing clinical practice guidelines. Canberra: National Health and Medical Research Council, 1999.Google Scholar

20 Dick B. Delphi face to face. 2000. (Available at: http://www.scu.edu.au/schools/gcm/ar/arp/delphi.html).Google Scholar

21 Marks P, Beumont PJV. Eating or dieting disorders. In: The missing link: adolescent mental health in general practice. Sydney: Alpha Biomedical, 2001; 95–111.Google Scholar

22 Goldner EM, Birmingham CL, Smye V. Addressing treatment refusal in anorexia nervosa. clinical, ethical and legal considerations. In: Garner DM, Garfinkel PE, eds. Handbook of treatments for eating disorders. 2nd edn. New York: Guilford, 1997; 450–461.Google Scholar

23 Zipfel S, Reas DL, Thornton CE et al. Day hospitalisation programs for eating disorders: a systematic review of the literature. International Journal of Eating Disorders 2002; 31:105–117.Crossref, Google Scholar

24 Thornton CE, Beumont PJV, Touyz SW. The Australian experience of day programmes for patients with eating disorders. International Journal of Eating Disorders 2002; 32:1–10.Crossref, Google Scholar

25 Touyz SW, Thornton CE, Rieger E, George L, Beumont PJV. The incorporation of the stage of change model in the day hospital treatment of patients with anorexia nervosa. European Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 2003; 12(Suppl.1):65–71.Crossref, Google Scholar

26 Buddeberg-Fischer B, Klaghofer R, Gnam G, Buddeberg C. Prevention of disturbed eating behaviour: a prospective intervention study in 14- to 19-year old Swiss students. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 1998; 98:146–155.Crossref, Google Scholar

27 O’Dea J, Abraham S. Improving body image, eating attitudes, and behaviours of young male and female adolescents: a new educational approach that focuses on self-esteem. International Journal of Eating Disorders 2000; 28:43–57.Crossref, Google Scholar

28 Pratt BM, Woolfenden SR. Interventions for preventing eating disorders in children and adolescents. Cochrane Library: Update 2003: Issue 1.Google Scholar

29 Mitchell JE. Eating disorders. In: Pomeroy C, Mitchell JE, Roerig J, Crow S, eds. Medical complications of psychiatric illness. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, 2001.Google Scholar

30 Beumont PJV, Russell JD, Touyz SW. Treatment of anorexia nervosa. Lancet 1993; 341:1635–1640.Crossref, Google Scholar

31 Touyz SW, Beumont PJV. Behavioural treatment to promote weight gain in anorexia nervosa. In: Garner DM, Garfinkel PE, eds. Handbook of treatments for eating disorders. 2nd edn. New York: Guilford, 1997; 361–371.Google Scholar

32 Touyz SW, Beumont PJV, Glaun D, Philips T, Cowie I. A comparison of lenient and strict operant conditioning programmes in refeeding patients with anorexia nervosa. British Journal of Psychiatry 1984; 144:517–520.Crossref, Google Scholar

33 Touyz SW, Lennerts W, Freeman RJ, Beumont PJV. To weigh or not to weigh? Frequency of weighing and rate of weight gain in patients with anorexia nervosa. British Journal of Psychiatry 1990; 157:752–754.Crossref, Google Scholar

34 Beumont PJV, Touyz SW. The nutritional management of anorexia and bulimia nervosa. In: Brownell KD, Fairburn CG, eds. Eating disorders and obesity: a comprehensive handbook. New York: Guilford, 1995; 306–312.Google Scholar

35 Vitousek KM, Watson S, Wilson GT. Enhancing motivation for change in treatment resistant eating disorders. Clinical Psychology Review 1998; 18:391–420.Crossref, Google Scholar

36 Rieger E, Touyz SW, Beumont PJV. The anorexia nervosa stages of change questionnaire: information regarding its psychometric properties. International Journal of Eating Disorders 2002; 32:24–38.Crossref, Google Scholar

37 Garner DM, Garfinkel PE. Handbook of treatment for eating disorders. 2nd edn. New York: Guilford, 1997.Google Scholar

38 Mondrahty NK, Birmingham CL, Touyz SW, Beumont PJV. A randomised controlled trial of olanzapine versus chlorpromazine in anorexia nervosa Australasian Psychiatry 2004; in press.Google Scholar

39 Birmingham, L. The chronic patient. In: Marks P, Beumont PJV, eds. Workbook for family doctors in the NSW Shared Care Project. Sydney: Department of Psychological Medicine, University of Sydney, 2002.Google Scholar

40 Meads C, Gold L, Burls A, Jobanputra P. Inpatient versus outpatient care for eating disorders. Birmingham: University of Birmingham, 1999.Google Scholar

41 Crisp AH, Norton K, Gowers S et al. A controlled study of the effect of therapies aimed at adolescent and family psychopathology in anorexia nervosa. British Journal of Psychiatry 1991; 159:325–333.Crossref, Google Scholar

42 Gowers S, Norton K, Halek C, Crisp AH. Outcome of outpatient psychotherapy in a random allocation treatment study of anorexia nervosa. International Journal of Eating Disorders 1994; 15:165–177.Crossref, Google Scholar

43 Freeman C. Day patient treatment for anorexia nervosa. British Review of Bulimia and Anorexia Nervosa 1992; 6:3–8.Google Scholar

44 Robin AL, Moye AW, Gilroy M, Dennis AB, Sikand A. A controlled comparison of family versus individual therapy for adolescents with anorexia nervosa. Journal of American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 1999; 38:1482–1489.Crossref, Google Scholar

45 Robin AL, Siegel PT, Koepke T, Moye AW, Tice S. Family therapy versus individual therapy for adolescent females with anorexia nervosa. Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics 1994; 15:111–116.Crossref, Google Scholar

46 Robin AL, Siegel PT, Moye A. Family versus individual therapy for anorexia: impact on family conflict. International Journal of Eating Disorders 1995; 17:313–322.Crossref, Google Scholar

47 Dare C, Eisler I, Russell G, Treasure J, Dodge L. Psychological therapies for adults with anorexia nervosa. British Journal of Psychiatry 2001; 178:216–221.Crossref, Google Scholar

48 Eisler I, Dare C, Russell GF, Szmukler G, le-Grange D, Dodge E. Family and individual therapy in anorexia nervosa. A 5-year follow-up. Archives of General Psychiatry 1997; 54:1025–1030.Crossref, Google Scholar

49 Russell GF, Szmukler GI, Dare C, Eisler I. An evaluation of family therapy in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. Archives of General Psychiatry 1987; 44:1047–1056.Crossref, Google Scholar

50 Geist R, Heinmaa M, Stephens D, Davis R, Katzman DK. Comparison of family therapy and family group psychoeducation in adolescents with anorexia nervosa. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 2000; 45:173–178.Crossref, Google Scholar

51 le Grange D, Eisler I, Dare C, Russell GFM. Evaluation of family treatments in adolescent anorexia nervosa: a pilot study. International Journal of Eating Disorders 1992; 12:347–357.Crossref, Google Scholar

52 Eisler I, Dare C, Hodes M, Russell G, Dodge E, le Grange D. Family therapy for adolescent anorexia nervosa: The results of a controlled comparison of two family interventions. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 2000; 41:727–736.Crossref, Google Scholar

53 Wallin U, Kronovall P, Majewski ML. Body awareness therapy in teenage anorexia nervosa: outcome after 2 years. European Eating Disorders Review 2000; 8:19–30.Crossref, Google Scholar

54 Channon S, de Silva P, Hemsley D, Perkins R. A controlled trial of cognitive-behavioural and behavioural treatment of anorexia nervosa. Behavioral Research and Therapy 1989; 7:529–535.Crossref, Google Scholar

55 Serfaty M, Turkington D, Heap M, Ledsham L, Jolley E. Cognitive therapy versus dietary counselling in the outpatient treatment of anorexia nervosa: effects of the treatment phase. European Eating Disorders Review 1999; 7:334–350.Crossref, Google Scholar

56 Eckert ED, Goldberg SC, Halmi KA, Casper RC, Davis JM. Behaviour therapy in anorexia nervosa. British Journal of Psychiatry 1979; 134:55–59.Crossref, Google Scholar

57 Hall A, Crisp AH. Brief psychotherapy in the treatment of anorexia nervosa: outcome at one year. British Journal of Psychiatry 1987; 151:185–191.Crossref, Google Scholar

58 Treasure J, Todd G, Brolly M, Tiller J, Nehmed A, Denman F. A pilot study of a randomised trial of cognitive analytical therapy versus educational behavioral therapy for adult anorexia nervosa. Behavior Research and Therapy 1995; 33:363–367.Crossref, Google Scholar

59 Bachar E, Latzer Y, Kreitler S, Berry EM. Empirical comparison of two psychological therapies. Self psychology and cognitive orientation in the treatment of anorexia and bulimia. Journal of Psychotherapy and Practice Research 1999; 8:115–128.Google Scholar

60 Hay P, Bacaltchuk J, Claudino A, Ben-Tovim D, Yong PY. Individual psychotherapy in the outpatient treatment of adults with anorexia nervosa. In: Cochrane Library Issue 4. Chichester: Wiley, 2003.Google Scholar

61 Szmukler GI, Young GP, Miller G et al. A controlled trial of cisapride in anorexia nervosa. International Journal of Eating Disorders 1995; 17:347–357.Crossref, Google Scholar

62 Attia E, Haiman C, Walsh BT, Flater SR. Does fluoxetine augment the inpatient treatment of anorexia nervosa? American Journal of Psychiatry 1998; 155:548–551.Crossref, Google Scholar

63 Biederman J, Herzog DB, Rivinus TM et al. Amitriptyline in the treatment of anorexia nervosa: a double-blind, placebocontrolled study. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology 1985; 5:10–16.Crossref, Google Scholar

64 Lacey JH, Crisp AH. Hunger, food intake and weight: the impact of clomipramine on a refeeding anorexia nervosa population. Postgraduate Medical Journal 1980; 56:79–85.Google Scholar

65 Crisp AH, Lacey JH, Crutchfield M. Clomipramine and ‘drive’ in people with anorexia nervosa: An inpatient study. British Journal of Psychiatry 1987; 150:355–358.Crossref, Google Scholar

66 Halmi KA, Eckert E, Falk JR et al. Cyproheptadine for anorexia nervosa (Letter). Lancet 1982; 1:1357–1358.Crossref, Google Scholar

67 Halmi KA, Eckert E, La Du TJ, Cohen J. Anorexia nervosa. Treatment efficacy of cyproheptadine and amitriptyline. Archives of General Psychiatry 1986; 43:177–181.Crossref, Google Scholar

68 Toledo MZ. Tratamiento de la anorexia nervsoa cno una asociacon ciproheptadina-vitamins. Revista Medica Caja Nacional de Segura Social 1970; 19:147–153.Google Scholar

69 Vigersky RA, Loriaux DL. The effect of cyproheptadine in anorexia nervosa: a double blind trial. In: Vigersky RA, ed. Anorexia nervosa. New York: Raven, 1977; 349–356.Google Scholar

70 Goldberg SC, Halmi K, Eckert ED, Casper R, Davis JM. Cyproheptadine in anorexia nervosa. British Journal of Psychiatry 1979; 134:67–70.Crossref, Google Scholar

71 Goldberg SC, Casper R, Eckert ED. Effects of cyproheptadine in anorexia nervosa. Psychopharmacology Bulletin 1980; 16:29–30.Google Scholar

72 Silbert MV. The weight gain effect of periactin in anorexic patients. South African Medical Journal 1971; 45:374–377.Google Scholar

73 Birmingham CL, Goldner EM, Bakan R. Controlled trial of zinc supplementation in anorexia nervosa. International Journal of Eating Disorders 1994; 15:251–255.Google Scholar

74 Safai-Kutti S. Oral zinc supplementation in anorexia nervosa. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 1990; 82:14–17.Crossref, Google Scholar

75 Vandereycken W, Meermann R. When can the patient be said to have recovered?. In: Vandereycken W, Meermann R, eds. Anorexia nervosa: a clinicians guide to treatment. New York: Walter De Gruyter, 1984; 237–250.Google Scholar

76 Vandereycken W, Pierloot R. Pimozide combined with behavior therapy in the short-term treatment of anorexia nervosa. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 1982; 66:445–450.Crossref, Google Scholar

77 Gross HA, Ebert MH, Faden VB, Goldberg SC, Nee LE, Kaye WH. A double-blind controlled trial of lithium carbonate primary anorexia nervosa. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology 1981; 1:376–381.Crossref, Google Scholar

78 Marrazzi MA, Bacon JP, Kinzie J, Luby ED. Naltrexone use in the treatment of anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. International Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology 1995; 10:163–726.Crossref, Google Scholar

79 Stacher G, Abatzi-Wenzel T, Wiesnagrotzki S, Bergmann H, Schneider C, Gaupmann G. Gastric emptying, body weight and symptoms in primary anorexia nervosa. Long term effects of cisapride. British Journal of Psychiatry 1993; 162:398–402.Crossref, Google Scholar

80 Kaye WH, Nagata T, Weltzin TE et al. Double-blind placebo controlled administration of fluoxetine in restricting and restricting-purging-type anorexia nervosa. Biological Psychiatry 2001; 49:644–652.Crossref, Google Scholar

81 Brambilla F, Draisci APA, Brunetta M. Combined cognitive-behavioral, psychopharmacological and nutritional therapy in bulimia nervosa. Neuropsychobiology 1995; 32:68–71.Crossref, Google Scholar

82 Neiderman M, Farley A, Richardson J, Lask B. Nasogastric feeding in children and adolescents with eating disorders: toward good practice. International Journal of Eating Disorders 2001; 29:441–448.Crossref, Google Scholar

83 Barren SA, Weltzin TE, Kaye WH. Low discharge weight and outcome in anorexia nervosa. American Journal of Psychiatry 1995; 152:1070–1072.Crossref, Google Scholar

84 Gross G, Russell JD, Beumont PJV et al. Longitudinal study of patients with anorexia nervosa 6–10 years after treatment. Impact of adequate weight restoration on outcome. Annals of the New York Academy of Science 2000; 4:614–616.Google Scholar

85 Thien V, Thomas A, Markin D, Birmingham CL. Pilot study of a graded exercise program for the treatment of anorexia nervosa. International Journal of Eating Disorders 2000; 28:101–106.Crossref, Google Scholar

86 Touyz SW, Beumont PJV. Anorexia nervosa: a follow-up investigation. Medical Journal of Australia 1984; 141:219–222.Crossref, Google Scholar

87 Crisp AH, Callender JS, Halek C, Hsu LKG. Long term mortality in anorexia nervosa. A 20 year follow-up of the St Georges and Aberdeen Cohorts. British Journal of Psychiatry 1992; 161:104–107.Crossref, Google Scholar

88 Ben-Tovim D, Walker K, Gilchrist P, Freemen R, Kalucy R, Esterman A. Outcome in patients with eating disorders: a 5-year study. Lancet 2001; 357:1254–1257.Crossref, Google Scholar

89 Grinspoon B, Baum H, Lee K, Anderson E, Herzog D, Klibanski A. Effects of short-term recombinant human insulin-like factor I administration on bone turnover in osteopenia women with anorexia nervosa. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 1996; 81:3864–3870.Google Scholar

90 Klibanski A, Biller BM, Schoenfeld DA, Herzog DB, Saxe VC. The effects of estrogen administration on trabecular bone loss in young women with anorexia nervosa. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 1995; 80:898–904.Google Scholar

91 Gordon CM, Grace E, Jean Emans S, Goodman E, Crawford MH, Leboff MS. Changes in bone turnover markers and menstrual function after short-term oral DHEA in young women with anorexia nervosa. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research 1999; 14:136–145.Crossref, Google Scholar

92 Treasure J, Schmidt U. Anorexia nervosa. Clinical Evidence 2001; 5:10–12.Google Scholar

93 Fairburn CG, Cooper Z, Doll HA, Welch SL. Risk factors for anorexia nervosa: Three integrated case-control comparisons. Archives of General Psychiatry 1999; 56:468–476.Crossref, Google Scholar

94 Beumont PJV. Anorexia nervosa as a mental and physical illness: The medical perspective. In: Gaskell D, Sanders F, eds. The encultured body: policy implications for healthy body image and disordered eating behaviours. Brisbane: Queensland University of Technology, 2000.Google Scholar