A Double-Blind Trial of Haloperidol, Chlorpromazine, and Lorazepam in the Treatment of Delirium in Hospitalized AIDS Patients

Abstract

Objective: The purpose of this study was to examine the efficacy and side effects of haloperidol, chlorpromazine, and lorazepam for the treatment of the symptoms of delirium in adult AIDS patients in a randomized, double-blind, comparison trial. Method: Nondelirious, medically hospitalized AIDS patients (N=244) consented to participate in the study and were monitored prospectively for the development of delirium. Patients entered the treatment phase of the study if they met DSM-III-R criteria for delirium and scored 13 or greater on the Delirium Rating Scale. Thirty patients were randomly assigned to treatment with haloperidol (N=11), chlorpromazine (N=13), or lorazepam (N=6). Efficacy and side effects associated with the treatment were measured with repeated assessments using the Delirium Rating Scale, the Mini-Mental State, and the Extrapyramidal Symptom Rating Scale. Results: Treatment with either haloperidol or chlorpromazine in relatively low doses resulted in significant improvement in the symptoms of delirium as measured by the Delirium Rating Scale. No improvement in the symptoms of delirium was found in the lorazepam group. Cognitive function, as measured by the Mini-Mental State, improved significantly from baseline to day 2 for patients receiving chlorpromazine. Treatment with haloperidol or chlorpromazine was associated with an extremely low prevalence of extrapyramidal side effects. All patients receiving lorazepam, however, developed treatment-limiting adverse effects. Although only a small number of patients had been treated with lorazepam, the authors became sufficiently concerned with the adverse effects to terminate that arm of the protocol early. Conclusions: Symptoms of delirium in medically hospitalized AIDS patients may be treated efficaciously with few side effects by using low-dose neuroleptics (haloperidol or chlorpromazine). Lorazepam alone appears to be ineffective and associated with treatment-limiting adverse effects.

Delirium is highly prevalent in the medically ill and is associated with greater morbidity and mortality, particularly if unrecognized and untreated (1–13). The prevalence of delirium in the hospitalized medically ill generally ranges from 10% to 30% (1–4). At greater risk for delirium are the elderly and postoperative, cancer, and AIDS patients (5–13). Approximately 30%–40% of medically hospitalized AIDS patients develop delirium (13), and as many as 65%–80% develop some type of organic mental disorder (14).

The standard approach to the management of delirium in the medically ill includes specific interventions directed at elucidating and correcting the underlying causes and more nonspecific interventions directed at controlling the symptoms of delirium. Important nonspecific interventions include psychosocial and environmental approaches, such as frequently orienting the patient, arranging visits by family members, and providing familiar objects from home. However, the mainstay of symptomatic treatment of delirium involves the use of pharmacotherapies including neuroleptic drugs, benzodiazepines, and other sedatives (15–19).

The literature on the pharmacological management of symptoms commonly associated with delirium includes an early series of controlled intervention trials that compared haloperidol and thioridazine (20–22) and thioridazine and diazepam (23) in the treatment of “agitation and psychotic” symptoms related to dementia (often with superimposed delirium) in geriatric populations. Two additional controlled trials compared haloperidol and droperidol (24) in “agitated and combative” emergency room patients with a variety of undefined organic mental disorders and functional disorders, and paraldehyde and diazepam (25) in medically hospitalized patients with alcohol withdrawal and “delirium tremens.” While these studies suggest a role for neuroleptics, benzodiazepines, and other sedatives in the management of symptoms such as those seen in delirium, it is not clear that these studies were, in fact, conducted in delirious populations. Rather, the groups studied appear to be heterogeneous cohorts of demented, delirious, and psychotic patients. There are, to date, no controlled trials of pharmacotherapy for delirium that use modern DSM terminology or valid delirium assessment measures.

There are, however, numerous clinical reports and uncontrolled trials that suggest the efficacy of a number of agents in the management of the symptoms of delirium (26, 27). Haloperidol, a potent dopamine-blocking neuroleptic agent, has emerged as the drug of choice in the symptomatic management of delirium in the medically ill, primarily because of its lack of sedative, autonomic, and cardiovascular (hypotensive) effects (28) and its availability in a variety of dosage forms (oral, tablet, liquid, intramuscular, and intravenous).

In the AIDS population, however, the choice of such a high-potency neuroleptic may not be ideal for treating delirium. Fernandez and colleagues (29) reported on their experience with high-dose intravenous haloperidol, in combination with lorazepam, in the management of delirium in terminally ill AIDS patients. While haloperidol was effective in managing agitation related to delirium, clinically significant extrapyramidal side effects emerged in a large percentage of patients. Other reports suggest that patients with AIDS may have an unacceptably high level of sensitivity to the extrapyramidal side effects of high-potency neuroleptics, which would potentially limit the clinical usefulness of potent dopamine-blocking agents (30–32).

In order to determine the safest and most effective pharmacotherapies for the management of the mental symptoms and behavioral disturbances associated with delirium in AIDS patients, we conducted a randomized, double-blind, comparison trial of haloperidol (a high-potency neuroleptic), chlorpromazine (a low-potency neuroleptic), and lorazepam (a benzodiazepine). Because efficacious drugs are available for the treatment of delirium, and withholding medication from agitated patients could pose a risk to staff and the patient, we felt that a placebo control group could not ethically be included (33).

Method

Subjects

Medically hospitalized adult patients who met the case definition for AIDS of the Centers for Disease Control (34) and were undergoing treatment for AIDS-related medical problems at the St. Luke’s/Roosevelt Hospital Center were approached for participation. Since informed consent could not ethically be obtained from subjects once delirium had developed, we devised a prospective research strategy in which only medically stable patients who had the capacity to give informed consent were recruited. While many patients exhibited clinical evidence of AIDS-related dementia, only those who lacked the capacity to give informed consent were not approached. The study was open to all volunteers regardless of gender, race, or HIV risk factor. Patients who agreed to participate were consenting to delirium treatment within the study protocol only in the event that a delirium episode developed at a later time. This study strategy was approved by the St. Luke’s/Roosevelt Hospital Center Institutional Review Board. Consent forms were available in Spanish and English, and bilingual research staff were available. Written informed consent was obtained, after the procedures of the study had been fully explained, from all subjects who participated in this study.

A total of 244 (59%) of the 412 patients approached, including 49 women, agreed to participate, were followed prospectively, and were monitored for onset of delirium. Patients who reported feeling too ill to consider participation were reapproached at a later time during hospitalization when their condition had stabilized. Enrolled patients were treated according to study protocol if they met DSM-III-R criteria for delirium and scored above the threshold score diagnostic for delirium (score of 13 or greater) on the Delirium Rating Scale. Exclusion criteria included known hypersensitivity to neuroleptics or benzodiazepines; presence of neuroleptic malignant syndrome; concurrent treatment with neuroleptic drugs; seizure disorder; current systemic chemotherapy for Kaposi’s sarcoma; withdrawal syndrome or anticholinergic delirium for which a more specific treatment was indicated; current or past diagnosis of schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, or bipolar disorder (i.e., mania or psychotic depression); and the study compromising medical treatment for the underlying etiology (i.e., delay in obtaining an emergency medical treatment such as hemodialysis). Efforts were made to also exclude patients in whom delirium appeared to be part of a terminal event (i.e., the patient was expected to die within 24 hours).

Thirty patients (12% of enrollment) became delirious and met criteria for treatment in the protocol during the 28-month data collection period. Twenty-three (77%) of these patients were men, and seven (23%) were women; 17 (57%) were black, eight (27%) were Hispanic, four (13%) were white, and one patient (3%) was Asian. The mean age of the patients was 39.2 years (SD=8.8, range=23–56). The average number of years of education was 13.4 (SD=3.7, range=8–22). HIV transmission risk factors in these patients included injection drug use in 14 (47%), homosexual contact in 12 (40%), heterosexual contact in five (17%), and transfusion in one patient (3%).

Measures

The following measures were used to monitor efficacy and side effects associated with the treatment of delirium.

Delirium Rating Scale.

The Delirium Rating Scale is a 10-item scale specifically integrating DSM-III criteria designed to be used by the clinician to identify delirium in the medically ill (35). The maximum possible score is 32. A score of 13 or above on the scale distinguished delirious patients from those with dementia or schizophrenia in the validation study by Trzepacz et al. (35). Reliability among the four treating psychiatrists was established (intraclass correlation coefficient=0.96).

Mini-Mental State(36).

Scores on the Mini-Mental State were used to separately track cognitive status change in relation to drug administration and change in delirium symptoms. The Mini-Mental State assesses orientation as well as cognitive capacity. Although a score of 23 (out of a possible 30) or below has generally been considered the cutoff for clinically significant cognitive impairment, new data have suggested the use of a tiered system of rating the degree of cognitive impairment, ranging from “none” to “severe” (37). In our study we used the patient’s total score on the Mini-Mental State to guide ratings of severity on item 6 (cognitive status) of the Delirium Rating Scale. A Mini-Mental State score of 28–30 was rated as 0 (no deficits) on item 6 of the Delirium Rating Scale, a score of 25–28 was rated as 1 (very mild deficits), a score of 20–24 was rated as 2 (focal deficits), a score of 15–19 was rated as 3 (significant deficits), and a score of 15 or less was rated as 4 (severe deficits).

Extrapyramidal Symptom Rating Scale.

The Extrapyramidal Symptom Rating Scale (38) consists of a subjective questionnaire of parkinsonian symptoms; an objective examination of parkinsonism, dystonia, and dyskinetic movements; and a clinical global impression of tardive dyskinesia. The objective parkinsonism subscale includes ratings of tremor, akathisia, expressive automatic movements, bradykinesia, rigidity, gait and posture, and sialorrhea. The maximum total score for this subscale is 108.

Other side effects were recorded daily on the Side Effects and Symptoms Checklist. Sociodemographic data collected included gender, race, date of birth, marital status, HIV risk transmission factor for AIDS, religion, and occupation. Two measures were used to estimate the patient’s functional status: the Karnofsky Performance Status (39), which estimates functional ability ranging from the ability to perform normal activities independently to total dependence, and the Medical Status Profile. The Medical Status Profile form allowed the study physician (K.C.) to record and categorize each specific illness from the chart and, on the basis of chart comments and laboratory data, to estimate the severity of the illness on the day delirium was diagnosed. Severity of each medical illness was scored on a 3-point scale (1=mild, 2=moderate, 3=severe). Categories included infections, malignancies, metabolic disturbances, blood disorders, organ system failure, computerized tomography scan findings, and nervous system disorders. The data generated a mean number of medical complications and a mean severity of complications.

Procedure

Research staff monitored study patients daily for signs of delirium. In addition, training was provided for medical and nursing staff, who alerted study staff to potentially delirious patients. If delirium was suspected, the study coordinator (M.M.P.) and a study psychiatrist (W.B., R.M., H.W., or S.L.) performed a full assessment.

Patients meeting criteria for delirium treatment were randomized by the hospital pharmacy and treated in a double-blind fashion with one of the three study drugs. Midway through the study, it became apparent that all the patients who received one of the study drugs developed treatment-limiting adverse side effects. Consistent with hospital policy, the study pharmacist determined which drug had been used to treat these patients. All of these patients had been treated with lorazepam. Lorazepam was removed from the study at that point. All subsequent patients were treated with the two remaining study drugs in a randomized, double-blind procedure.

A treatment protocol for study drug administration was followed (table 1). Each delirious patient was evaluated hourly with the Delirium Rating Scale (including the Mini-Mental State) and the Extrapyramidal Symptom Rating Scale. At the end of each hour, if the patient’s score on the Delirium Rating Scale was still 13 or greater, the next level dose of study drug was administered. After stabilization, that is, when the patient was asleep, calm, and not hallucinating or had scored 12 or below on the Delirium Rating Scale, a maintenance dose was started on day 2 and continued for up to 6 days of treatment protocol. The maintenance dose was equal to one-half of the first 24-hour dose requirement, given in a twice-a-day regimen. Medical staff were informed of the delirium diagnosis concurrently with the initiation of the treatment trial so that a search for the cause of the episode and appropriate medical management could be initiated. Completion of medical evaluation and treatment of the cause often required several days after the study drug was initiated.

Statistical analysis

In order to examine drug efficacy, scores on the Delirium Rating Scale and Mini-Mental State were entered into separate 3 (drug: haloperidol, chlorpromazine, lorazepam) × 3 (time: baseline, day 2, end of treatment) repeated measures multivariate analyses of variance (ANOVAs) (40). Of particular interest were the presence of interactions among the types of drug administered and changes in scores on the Delirium Rating Scale and Mini-Mental State over time. We performed simple effects analyses to identify which drug or drugs produced changes in delirium and mental status scores over time. Separate analyses were conducted to identify changes between baseline and day 2 and between day 2 and end of treatment. For the Extrapyramidal Symptom Rating Scale, only the parkinsonism subscale was used in statistical analyses similar to those used for the efficacy data described previously.

Results

Subjects

The mean Karnofsky Performance Status score for the 30 patients was 52.3 (SD=21.3, range=10–90). ANOVA showed that there were no significant differences among drug treatment groups in age, education, or Karnofsky scores.

Medical Status Profile data showed that patients had multiple medical complications (mean=12.57, SD=4.1, range=6.00–22.00). Most common were hematologic and metabolic disorders (e.g., anemia, leukopenia, thrombocytopenia, hypoalbuminemia) and infectious diseases (e.g., septicemia, systemic fungal infections, pneumocystis carinii pneumonia, tuberculosis, and disseminated viral infections). Severity of medical complications for the study group was in the moderate to severe range (mean=2.44, SD=3.1, range=1.75–2.87). There were no differences (ANOVA) among groups in number of medical complications (F=1.21, df=2, 23, p<0.32) or severity of these complications (F=0.51, df=2, 23, p<0.61).

The context and course of the delirium episode varied among patients. Multiple etiologies, rather than a single etiology, usually accounted for the delirium episode. Some deliria occurred in the context of major organ system failure or during the dying process, which limited the effectiveness of treatment. In other cases, the delirium was a temporary phenomenon in a healthier patient and was treated successfully. Five patients (two in the haloperidol group, two in the chlorpromazine group, and one in the lorazepam group) died within 8 days of initiation of the protocol. Four patients (three in the chlorpromazine group and one in the lorazepam group) died within 1 week after completing the protocol. Seventeen patients lived longer than 2 weeks following day 1 of the protocol (mean=183 days, range=19–1,305). Four patients were known to have lived for a minimum of 2–7 months (mean=70 days) following treatment, but their specific date of death was not known.

Drug treatment

The 30 delirious patients were randomly assigned to treatment with haloperidol (N=11), chlorpromazine (N=13), or lorazepam (N=6). Mean drug doses administered during the first 24 hours of treatment were as follows: haloperidol, 2.8 mg (SD=2.4, range=0.8–6.3); chlorpromazine, 50.0 mg (SD=23.1, range=10–70); and lorazepam, 3.0 mg (SD=3.6, range=0.5–10.0). Average maintenance drug doses (day 2 to end of treatment) were as follows: haloperidol, 1.4 mg (SD=1.2, range=0.4–3.6); chlorpromazine, 36.0 mg (SD=18.4, range=10.0–80.0); and lorazepam=4.6 mg (SD=4.7, range=1.3–7.9).

Efficacy

Delirium Rating Scale scores for the total group (N=30) averaged 20.1 at baseline (SD=3.5, range=14–28), 13.3 on day 2 (SD=6.1, range=3–26), and 12.8 at the end of treatment (SD=6.4, range=3–26). Mini-Mental State scores for the group averaged 12.7 (SD=7.6, range=0–26) at baseline, 16.8 (SD=9.8, range=0–30) on day 2, and 15.1 (SD=10.6, range=0–30) at the end of treatment.

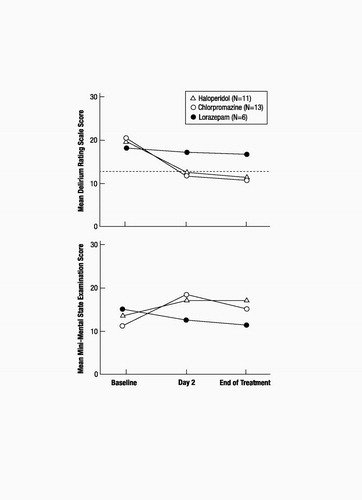

Delirium symptoms, as measured by the Delirium Rating Scale, improved, to values below the diagnostic threshold for delirium, for both the haloperidol and chlorpromazine groups but not for the lorazepam group. This improvement occurred in the neuroleptic drug groups within the first 24 hours of treatment (between baseline and day 2), and there was little or no further improvement between day 2 and the end of treatment. Delirium Rating Scale scores for the haloperidol group averaged 20.45 (SD=3.45) at baseline, 12.45 (SD=5.87) on day 2, and 11.64 (SD=6.10) at the end of treatment. Delirium Rating Scale scores for the chlorpromazine group averaged 20.62 (SD=3.88) at baseline, 12.08 (SD=6.50) on day 2, and 11.85 (SD=6.74) at the end of treatment. Delirium Rating Scale scores for the lorazepam group averaged 18.33 (SD=2.58) at baseline, 17.33 (SD=4.18) on day 2, and 17.00 (SD=4.98) at the end of treatment. Analysis of changes in delirium scale scores revealed a main effect for time (F=10.09, df=2, 27, p<0.001) but not for drug (F=0.84, df=2, 27, p<0.44). Simple effects analyses were conducted on the basis of a priori hypotheses regarding between-drug differences in efficacy and were supported by the overall drug-by-time interaction, which approached significance (F=2.27, df=4, 54, p<0.07). As shown in figure 1, there was a significant decrease in Delirium Rating Scale scores from baseline to day 2 for the two neuroleptic groups but not for the lorazepam group (haloperidol: F=27.50, df=1, 27, p<0.001; chlorpromazine: F= 37.02, df=1, 27, p<0.001; lorazepam: F=0.23, df=1, 27, p<0.63). There were no significant changes for any of the three drug groups in delirium scale scores from day 2 to the end of treatment (haloperidol: F=0.63, df=1, 27, p<0.43; chlorpromazine: F=0.06, df=1, 27, p<0.81; lorazepam: F=0.06, df=1, 27, p<0.81).

Cognitive status, as measured by the Mini-Mental State, improved between baseline and day 2 for the neuroleptic groups, but that improvement was significant only for the chlorpromazine group. The lorazepam group did not show improvement. There was no further improvement between day 2 and the end of treatment for any of the drug groups. Mini-Mental State scores for the haloperidol group averaged 13.45 (SD=6.95) at baseline, 17.27 (SD=8.87) on day 2, and 17.18 (SD=12.12) at the end of treatment. Mini-Mental State scores for the chlorpromazine group averaged 10.92 (SD=8.87) at baseline, 18.31 (SD=10.61) on day 2, and 15.08 (SD=10.43) at the end of treatment. Mini-Mental State scores for the lorazepam group averaged 15.17 (SD=5.31) at baseline, 12.67 (SD=10.23) on day 2, and 11.50 (SD=8.69) at the end of treatment. Analysis of changes in Mini-Mental State scores revealed a main effect for time that approached significance (F=2.91, df=2, 26, p<0.07) but not a main effect for drug (F=0.22, df=2, 27, p<0.81). The drug-by-time interaction approached significance (F=2.22, df=4, 54, p<0.08). As shown in figure 1, scores on the Mini-Mental State improved significantly from baseline to day 2 for patients treated with chlorpromazine (F=13.99, df=1, 27, p<0.001); there was a trend toward improvement for those treated with haloperidol (F=3.16, df=1, 27, p<0.09), but there was no evidence of improvement for patients treated with lorazepam (F=0.74, df=1, 27, p<0.40). Scores on the Mini-Mental State from day 2 to end of treatment declined for patients treated with chlorpromazine (F=4.68, df=1, 27, p<0.04) and did not significantly change for patients treated with either of the other two drugs (haloperidol: F=00, df=1, 27, p<0.96; lorazepam: F=0.28, df=1, 27, p<0.60).

Early terminations/side effects.

All six patients who received lorazepam developed treatment-limiting side effects, including oversedation, disinhibition, ataxia, and increased confusion, leading to refusal to take the drug or requiring discontinuation of the drug. As noted earlier, because of the experience of these patients, lorazepam was removed from the protocol, and all remaining patients were randomly assigned to either haloperidol or chlorpromazine. No clinically significant medication-related side effects were noted in the neuroleptic drug groups during the trial period.

Extrapyramidal side effects.

None of the patients in the study developed dystonic or dyskinetic symptoms during the period of drug therapy. Extrapyramidal symptoms were noted only on the objective parkinsonism subscale of the Extrapyramidal Symptom Rating Scale, and they were limited primarily to decreased expressive automatic movements, rigidity, tremor, and mild akathisia. Scores on the parkinsonism subscale were extremely low at baseline before medication (haloperidol: mean=7.00, SD=6.80; chlorpromazine: mean=7.42, SD=8.08; lorazepam: mean=7.60, SD=10.11) and during maintenance therapy (haloperidol: mean=5.54, SD=6.76; chlorpromazine: mean=5.08, SD=4.48; lorazepam: mean=12.20, SD=8.93). Analysis of changes in Extrapyramidal Symptom Rating Scale scores (baseline to maintenance) revealed no effect for time (F=0.06, df=1, 27, p<0.81) or drug (F=0.61, df=2, 25, p<0.55) and a trend toward significance for drug-by-time interaction (F=2.98, df=2, 25, p<0.07). This interaction appeared to be due to an increase in extrapyramidal side effects in the lorazepam group. However, because of the small number of patients in the lorazepam group (N=5; one subject refused to complete the examination), caution should be used in interpreting these data; further analysis was not pursued.

Discussion

We have conducted the first double-blind, randomized comparison trial of pharmacotherapies for the management of delirium in the medically ill. Our findings confirm the clinical efficacy of neuroleptic drugs (haloperidol and chlorpromazine) in the amelioration of the symptoms of delirium in AIDS patients. This improvement occurred within the first 24 hours, usually before the initiation of interventions directed at the medical etiologies of the delirium, and required relatively low doses of neuroleptic drugs (e.g., 2.80 mg of haloperidol in the first 24 hours). Our findings also suggest that a benzodiazepine (lorazepam) alone is ineffective in the treatment of delirium in AIDS patients and, in fact, may worsen symptoms. Both haloperidol and chlorpromazine seemed to be equally effective in relieving the symptoms of delirium, as measured by the Delirium Rating Scale. Cognitive functioning, as measured by the Mini-Mental State, improved significantly from baseline to day 2 for patients receiving chlorpromazine, and there was a trend toward a significant improvement for patients receiving haloperidol. Patients receiving lorazepam did not improve and, in fact, showed increased cognitive impairment. Cognitive functioning (Mini-Mental State scores) decreased significantly from day 2 to end of treatment for the chlorpromazine group, suggesting the possibility that anticholinergic effects over time may have influenced cognitive improvement. It is noteworthy that Mini-Mental State scores remained in the impaired range, even after delirium cleared, in our study group, which consisted primarily of patients with advanced AIDS, concurrent AIDS dementia, and a history of polysubstance abuse (41–43).

Our findings suggest that the doses of neuroleptics required to effectively manage delirium in AIDS patients may be considerably lower than many reported clinical standards (1, 27, 44). The efficacy of such low-dose regimens of neuroleptic agents may be related to a number of factors, including altered pharmacokinetics in severely ill and debilitated patients. Age, gender, premorbid condition, and magnitude of medical complications may all be important determinants not only of susceptibility to delirium, but also of response to pharmacological treatment of delirium (1, 8, 45). Responsivity and sensitivity to low-dose neuroleptics is a general phenomenon reported in other medically debilitated patient groups, such as the elderly or those with cancer. It is noteworthy that others (46–48) have reported using up to 100 mg of parenteral haloperidol/day to control the symptoms of postoperative delirium in patients with relatively limited degrees of chronic medical debilitation.

There may, however, be disease-specific mechanisms to explain why patients with AIDS required such low doses of neuroleptics to manage the symptoms of delirium. The clinical literature indicates that patients with AIDS have a greater sensitivity to the extrapyramidal side effects of dopamine-blocking drugs (e.g., antiemetics, neuroleptics) (31, 32, 49). Histopathologic studies suggest that the neurotropic HIV appears to have a predilection for invading the subcortical structures of the brain (50). Positron emission tomography scan studies of the brains of patients with AIDS demonstrate alterations in the metabolism of the basal ganglia, with hypermetabolism early in HIV disease followed by hypometabolism in later stages (51). While the precise mechanisms remain unclear, such reports suggest that the HIV effects on subcortical structures of the brain may result in increased sensitivity to the effects of neuroleptic drugs. Consequently, lower doses may be required to provide effective control of the symptoms of delirium.

The timing of the initiation of pharmacotherapy in the course of a delirium episode may also influence dosage requirements. Because of the methodology in our study (i.e., close daily monitoring of patients for signs of delirium), we generally initiated treatment during the first 24 to 48 hours of delirium onset. It is possible that such “early” intervention allowed for response to lower doses than might have been required if delirium were more established (e.g., 3–5 days).

In contrast to our findings with neuroleptics, lorazepam was not effective in resolving delirium or significantly improving the symptoms of delirium. In fact, use of lorazepam resulted in intoxication or worsening of symptoms and treatment-limiting side effects that required removal from protocol. Lorazepam appeared to merely sedate patients, reducing level of consciousness and awareness of the environment, or to produce idiosyncratic or paradoxical agitation. Caution should be used in generalizing these data on the use of lorazepam since our study group size was small, doses were relatively low and limited to oral or intramuscular administration, and the population was limited to AIDS patients. We did not test the use of lorazepam in larger doses or in combination with a neuroleptic.

Systematic assessment of treatment/medication-related side effects was difficult in this seriously medically ill patient group with severely limited ability to communicate during periods of delirium. Assessment of extrapyramidal symptoms or side effects by using the Extrapyramidal Symptom Rating Scale was, however, more feasible because of the objective and nonverbal nature of the clinical examination (e.g., physical examination for tremor, rigidity, and so forth). There was no significant increase in extrapyramidal side effects in patients receiving neuroleptic drugs. The parkinsonian symptoms observed in the patients during drug treatment were essentially those noted on their Extrapyramidal Symptom Rating Scale before initiation of study drug (e.g., psychomotor slowing) and were consistent with the types of extrapyramidal symptoms noted to occur in patients with late-stage AIDS and neurological complications (e.g., AIDS dementia) who have not been exposed to dopamine-blocking drugs (52).

Our study is an important first step in helping to define standards for optimal management of delirium in medically hospitalized patients. While we demonstrated that early intervention with neuroleptic agents in low doses is useful in managing delirium in AIDS patients, further studies are needed to confirm our findings and to expand the scope of delirium intervention research to include studies of pharmacologic versus nonpharmacologic treatments, drug combinations, new antipsychotic agents (e.g., risperidone), and diverse patient populations.

| Dose (mg/hour) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Haloperidol | Chlorpromazine | Lorazepam | ||||

| Dose Level | Oral | Intra-muscular | Oral | Intra-muscular | Oral | Intra-muscular |

| 1 | 0.25 | 0.125 | 10 | 5 | 0.50 | 0.20 |

| 2 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 20 | 10 | 1.00 | 0.50 |

| 3 | 1.00 | 0.50 | 40 | 20 | 1.50 | 0.70 |

| 4 | 2.00 | 1.00 | 80 | 40 | 2.00 | 1.00 |

| 5 | 2.50 | 1.50 | 100 | 50 | 2.50 | 1.25 |

| 6 | 2.50 | 1.50 | 100 | 50 | 2.50 | 1.25 |

| 7 | 2.50 | 1.50 | 100 | 50 | 2.50 | 1.25 |

| 8 | 5.00 | 3.00 | 200 | 100 | 4.00 | 2.00 |

| 9 | 5.00 | 3.00 | 200 | 100 | 4.00 | 2.00 |

Figure 1. Delirium Rating Scale Scoresa and Mini-Mental State Scores of AIDS Patients in Three Treatment Groups From Baseline to Day 2 and End of Treatment

a Dotted line indicates threshold score of 13, at which patients were identified as delirious.

1 Lipowski ZJ: Delirium (acute confusional states). JAMA 1987; 258: 1789–1792Crossref, Google Scholar

2 Rabins PV, Folstein MF: Delirium and dementia: diagnostic criteria and fatality rates. Br J Psychiatry 1982; 140:149–153Crossref, Google Scholar

3 Tune LE: Post-operative delirium. Int Psychogeriatr 1991; 3:325–332Crossref, Google Scholar

4 Lipowski ZJ: Delirium: Acute Confusional States. New York, Oxford University Press, 1990Google Scholar

5 Derogatis LR, Morrow GR, Fetting J, Penman D, Piasetsky S, Schmale AM, Hendricks M, Carnicke C: The prevalence of psychiatric disorders among cancer patients. JAMA 1983; 249:751–757Crossref, Google Scholar

6 Fleishman S, Lesko LM: Delirium and dementia, in Handbook of Psychooncology. Edited by Holland J, Rowlands JH. New York, Oxford University Press, 1989, pp 342–355Google Scholar

7 Posner JB: Delirium and exogenous metabolic brain disease, in Cecil-Loeb Textbook of Medicine, 17th ed. Edited by Beeson PB, McDermott W. Philadelphia, WB Saunders, 1975, pp 1973–1975Google Scholar

8 Stiefel FC, Holland JC: Delirium in cancer patients. Int Psychogeriatr 1991; 3:333–336Crossref, Google Scholar

9 Gillick MR, Serrell NA, Gillick LS: Adverse consequences of hospitalization in the elderly. Soc Sci Med 1987; 3:533–539Google Scholar

10 Francis J, Martin D, Kapoor WN: A prospective study of delirium in hospitalized elderly. JAMA 1990; 263:1097–1101Crossref, Google Scholar

11 Massie MJ, Holland J, Glass E: Delirium in terminally ill cancer patients. Am J Psychiatry 1983; 140:1048–1050Crossref, Google Scholar

12 Weddington WW: The mortality of delirium: an underappreciated problem? Psychosomatics 1982; 23:1232–1235Crossref, Google Scholar

13 Breitbart W, Marotta R, Platt M, Corbera K: Pharmacologic management of delirium in medically hospitalized AIDS patients, in Abstracts of the 37th Annual Meeting of the Academy of Psychosomatic Medicine. Chicago, APM, 1990Google Scholar

14 Perry SW: Organic mental disorders caused by HIV: update on early diagnosis and treatment. Am J Psychiatry 1990; 147:696–710Crossref, Google Scholar

15 Lipowski ZJ: Delirium: Acute Brain Failure in Man. Springfield, Ill, Charles C Thomas, 1980, pp 206–226Google Scholar

16 Cohen BM, Lipinski JF: Treatment of acute psychosis with non-neuroleptic agents. Psychosomatics 1986; 27:7–14Crossref, Google Scholar

17 Salzman C, Green AI, Rodriguez-Villa F, Jaskiw GI: Benzodiazepines combined with neuroleptics for management of severe disruptive behavior. Psychosomatics 1986; 27(Jan suppl):17–22Crossref, Google Scholar

18 Lenox RH, Modell JG, Weiner S: Acute treatment of manic agitation with lorazepam. Psychosomatics 1986; 27(Jan suppl):28–32Crossref, Google Scholar

19 Adams R: Neuropsychiatric evaluation and treatment of delirium in the critically ill cancer patient. Cancer Bull 1984; 36:156–160Google Scholar

20 Rosen HS: Double-blind comparison of haloperidol and thioridazine in geriatric outpatients. J Clin Psychiatry 1979; 40:17–20Google Scholar

21 Smith GR, Taylor CW, Linkous P: Haloperidol versus thioridazine for the treatment of psychogeriatric patients: a double-blind clinical trial. Psychosomatics 1974; 15:134–138Crossref, Google Scholar

22 Tsuang MM, Lu LM, Stotsky BA, Cole JO: Haloperidol versus thioridazine for hospitalized psychogeriatric patients: double-blind study. J Am Geriatr Soc 1971; 9:593–600Google Scholar

23 Kirven LE, Montero EF: Comparison of thioridazine and diazepam on the control of nonpsychotic symptoms associated with senility: double-blind study. J Am Geriatr Soc 1973; 12:546–551Google Scholar

24 Thomas H, Schwartz E, Petrilli R: Droperidol versus haloperidol for chemical restraint of agitated and combative patients. Ann Emerg Med 1992; 21:407–413Crossref, Google Scholar

25 Thompson WL, Johnson AD, Maddrey WL, Osler Medical Housestaff: Diazepam and paraldehyde for treatment of severe delirium tremens. Ann Intern Med 1975; 82:175–180Crossref, Google Scholar

26 Adams F, Fernandez F, Andersson BS: Emergency pharmacotherapy of delirium in the critically ill cancer patient. Psychosomatics 1986; 27:33–38Crossref, Google Scholar

27 Muskin PR, Mellman LA, Kornfeld DS: A “new” drug for treating agitation and psychosis in the general hospital: chlorpromazine. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 1986; 8:404–410Crossref, Google Scholar

28 Settle EC, Ayd FJ Jr: Haloperidol: a quarter century of experience. J Clin Psychiatry 1983; 44:440–445Google Scholar

29 Fernandez F, Levy JK, Mansell PWA: Management of delirium in terminally ill AIDS patients. Int J Psychiatry Med 1984; 19:33–35Google Scholar

30 Hriso E, Kuhn T, Masdeu JC, Grundman M: Extrapyramidal symptoms due to dopamine-blocking agents in patients with AIDS encephalopathy. Am J Psychiatry 1991; 148:1558–1561Crossref, Google Scholar

31 Edelstein H, Knight RT: Severe parkinsonism in two AIDS patients taking prochlorperazine. Lancet 1987; 2:341–342Crossref, Google Scholar

32 Hollander H, Golden J, Mendelson T, Cortland D: Extrapyramidal symptoms in AIDS patients given low-dose metoclopramide or chlorpromazine (letter). Lancet 1987; 2:1186Google Scholar

33 Rothman KJ, Michels KB: The continuing unethical use of placebo controls (letter). N Engl J Med 1994; 331:394–398Crossref, Google Scholar

34 Revision of the CDC surveillance case definition for acquired immunodeficiency syndrome: Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists, AIDS Program, Center for Infectious Diseases. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 1987; 36(suppl 1):1S–15SGoogle Scholar

35 Trzepacz PT, Baker RW, Greenhouse J: A symptom rating scale for delirium. Psychiatry Res 1988; 23:89–97Crossref, Google Scholar

36 Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR: “Mini-Mental State”: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 1975; 12:189–198Crossref, Google Scholar

37 Tombaugh TN, McIntyre NJ: The Mini-Mental State examination: a comprehensive review. J Am Geriatr Soc 1992; 40:922–935Crossref, Google Scholar

38 Chouinard G, Chouinard AR, Annable L, Jones BD: Extra-pyramidal symptom rating scale (abstract). Can J Neurol Sci 1980; 3:233Google Scholar

39 Karnofsky DA, Burchenal JH: The clinical evaluation of chemotherapeutic agents in cancer, in Evaluation of Chemotherapeutic Agents. Edited by Macleod CM. New York, Columbia University Press, 1949, pp 191–205Google Scholar

40 O’Brien RG, Kaiser MK: MANOVA method for analyzing repeated measures designs: an extensive primer. Psychol Bull 1985; 97:316–333Crossref, Google Scholar

41 Navia BA, Jordan B, Price RW: The AIDS Dementia Complex, I: clinical features. Ann Neurol 1986; 19:517–524Crossref, Google Scholar

42 Miller L: Neuropsychological assessment of substance abusers: review and recommendations. J Subst Abuse Treat 1985; 2:5–17Crossref, Google Scholar

43 Rubinow DR, Berrettini CH, Brouwers P, Lane HC: Neuropsychiatric consequences of AIDS. Ann Neurol 1988; 23(suppl):S24–S26Crossref, Google Scholar

44 Gelfand SB, Indelicato J, Benjamin J: Using intravenous haloperidol to control delirium. Hosp Community Psychiatry 1992; 43:215Google Scholar

45 Lipowski ZJ: Delirium in the elderly patient. N Engl J Med 1989; 320: 578–582Crossref, Google Scholar

46 Levenson JL: High-dose intravenous haloperidol for agitated delirium following lung transplantation. Psychosomatics 1995; 36:66–68Crossref, Google Scholar

47 Sanders KM, Murray GB, Cassem NH: High-dose intravenous haloperidol for agitated delirium in a cardiac patient on intra-aortic balloon pump (letter). J Clin Psychopharmacol 1991; 11:146–147Crossref, Google Scholar

48 Tesar GE, Murray GB, Cassem NH: Use of high-dose intravenous haloperidol in the treatment of agitated cardiac patients. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1985; 5:44–47Crossref, Google Scholar

49 Breitbart W, Marotta RF, Call P: AIDS and neuroleptic malignant syndrome. Lancet 1988; 2:1488–1489Crossref, Google Scholar

50 Navia BA, Cho ES, Petito CK, Price RW: The AIDS dementia complex, II: neuropathology. Ann Neurol 1986; 19:525–535Crossref, Google Scholar

51 Rottenberg DA, Moeller JR, Strother SC, Sidtis JJ, Navia BA, Dhawan V, Ginos JZ, Price RW: The metabolic pathology of the AIDS dementia complex. Ann Neurol 1987; 22:700–706Crossref, Google Scholar

52 Nath P, Jankovic J, Pettigrew LC: Movement disorders and AIDS. Neurology 1987; 37:37–41Crossref, Google Scholar