Differential Responses to Psychotherapy Versus Pharmacotherapy in Patients With Chronic Forms of Major Depression and Childhood Trauma

Abstract

Major depressive disorder is associated with considerable morbidity, disability, and risk for suicide. Treatments for depression most commonly include antidepressants, psychotherapy, or the combination. Little is known about predictors of treatment response for depression. In this study, 681 patients with chronic forms of major depression were treated with an antidepressant (nefazodone), Cognitive Behavioral Analysis System of Psychotherapy (CBASP), or the combination. Overall, the effects of the antidepressant alone and psychotherapy alone were equal and significantly less effective than combination treatment. Among those with a history of early childhood trauma (loss of parents at an early age, physical or sexual abuse, or neglect), psychotherapy alone was superior to antidepressant monotherapy. Moreover, the combination of psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy was only marginally superior to psychotherapy alone among the childhood abuse cohort. Our results suggest that psychotherapy may be an essential element in the treatment of patients with chronic forms of major depression and a history of childhood trauma.

Mood disorders are common illnesses, and major depression is the most common, affecting ≈17% of the population in the United States in their lifetime, with women (21.3%) having a higher prevalence rate than men (12.7%) (1). Depression is associated with significant morbidity, disability (loss of work days, reduced quality of life), increased medical comorbidity (cardiovascular disease and stroke), and mortality (increased risk for suicide and death from comorbid medical disorders) (2–4). Effective treatments for depression are available, including a variety of antidepressants, electroconvulsive therapy, and certain types of targeted psychotherapy such as cognitive-behavioral and interpersonal therapy (5). Research comparing antidepressant medication to cognitive-behavioral and interpersonal psychotherapy has generally found that both are equally effective for nonpsychotic forms of depression (6, 7). The combination of antidepressant medication and psychotherapy seems to provide only a modest increment in efficacy, although there may be some patients for whom combination therapy is more effective than medication or psychotherapy alone (8, 9).

Unfortunately, there are few predictors of response to any particular treatment, leaving both patients and clinicians to engage in often multiple trial and error attempts to identify the preferred treatment. In general, constellations of particular symptoms, such as the presence of a sleep disturbance or anxiety, have not proved helpful in predicting response to one or another pharmacological or psychotherapeutic treatment (10). One notable exception is the clear demonstration that major depression with psychotic features requires treatment with a combination of both antidepressant and antipsychotic medications or electroconvulsive therapy (11). Another exception is the superior efficacy of monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) in the treatment of depression with atypical features, e.g., hypersomnia, hyperphagia, mood reactivity, interpersonal rejection sensitivity, ‘‘leader limb’’ paralysis, and reverse diurnal mood variation. When to recommend psychotherapy, antidepressant medication, or the combination for a given patient with nonpsychotic depression remains unclear. In a large, multicenter study comprised of 681 patients, Keller et al. (8) reported that 12-week treatment with the combination of an antidepressant, nefazodone, and Cognitive Behavioral Analysis System of Psychotherapy (CBASP) was superior in efficacy to either monotherapy in the treatment of chronic forms of major depression, i.e., Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV; ref. 12) criteria for a current episode of chronic major depressive disorder (MDD), MDD superimposed on a preexisting dysthymic disorder, or recurrent MDD with incomplete remissions and a total duration of illness of at least 2 years. CBASP is a structured, time-limited psychotherapy specifically developed to treat chronic depression that includes elements of traditional cognitive-behavioral therapy and interpersonal therapy. It utilizes a technique called situational analysis to help patients understand the consequences of their behavior and interactions with others, alter patterns of coping, and improve interpersonal skills (13).

Several well established risk factors increase an individual’s likelihood of developing depression, including female gender, family history for depression, past personal history of depression, and early life trauma (14). Indeed, exposure to extraordinary life stressors in the prepubertal period, such as loss of parents or sexual or physical abuse has been well documented to increase the risk for depression and suicide (15–17). Whether depression associated with the presence of one or more of these risk factors responds preferentially to one or another effective treatment for depression has been little studied, although some evidence suggests that women and men may differ in their response to tricyclic antidepressants compared to the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) (18). No data exist as to whether a positive family history of depression, one of the major risk factors for depression, is associated with a better response to one of the available effective treatments for depression.

In this retrospective analysis of the large chronic-depression study cited above (8) comparing an antidepressant (nefazodone), a form of psychotherapy (CBASP), and their combination, we report that patients with chronic depression responded differently to the treatments depending on the presence or absence of early life trauma.

Methods

The large, multicenter study on treatment responses in chronic depression was previously described in detail by Keller et al. (8). We used the identical sample for the present investigation. A total of 681 patients, 18 to 75 years of age, with chronic forms of MDD, i.e., Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (12) criteria for a current episode of chronic MDD, MDD superimposed on a preexisting dysthymic disorder, or recurrent MDD with incomplete remissions and a total duration of illness of at least 2 years, were randomly assigned to 12 weeks of treatment with nefazodone, CBASP, or their combination. The Childhood Trauma Scale (19), administered at baseline, was used to assess the presence of early life adverse events. This scale quantifies childhood adverse experiences in the following categories: parental loss, physical abuse, sexual abuse and neglect, and any trauma. The 24-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HRSD24), a standard method to measure depression severity, obtained both at baseline and after 12 weeks of treatment, was the main depression-severity treatment-outcome measure. We evaluated the effect of the presence or absence of histories of childhood adversity (parental loss, physical abuse, sexual abuse, neglect) on delta HRSD24 scores (baseline minus exit score) in a completer analysis by using a general linear model with two factors (treatment and childhood adverse experience). Results were controlled for effects of age, sex, race, and depression severity at baseline. Last Observation Carried Forward (LOCF) analysis was used to evaluate the effect of presence or absence of histories of childhood adversity on remission rates, in addition to logistic modeling in completers. Odds ratios for achieving remission were calculated as a function of childhood adversity based on the LOCF data. Remission was defined as an exit HRSD24 score of ≤8, which is generally considered to represent complete recovery from depression with minimal, if any, residual symptoms (20).

Results

The treatment group prevalence of traumatic child abuse experiences in our sample of patients with chronic depression is presented in Table 1. In this population of patients with chronic forms of depression, approximately one-third experienced parental loss before age 15 years, 45% experienced childhood physical abuse, 16% experienced childhood sexual abuse, and 10% experienced neglect. These findings alone highlight the remarkably high prevalence rate of early life trauma in patients with chronic forms of major depression. Patients with early life adverse experiences did not differ from patients without early life trauma in drop-out rates during the study.

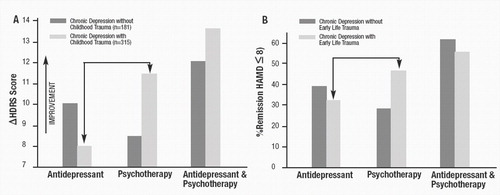

Results regarding treatment responses differed dramatically from those initially reported by Keller et al. (8), when groups were stratified according to the presence or absence of childhood trauma. There were significant interactions of effects of treatment type and parental loss (F=4.46, df=1,495, P=0.0121), physical abuse (F=3.25, df=1,495, P=0.03), neglect (F=4.82, df=1,495, P=0.0084), and any trauma (F=3.13, df=1,495, P=0.0446). Specifically, among patients with no history of childhood abuse/early trauma, there was a clear-cut stepwise order of treatment efficacy (combination > nefazodone ≅ CBASP). In contrast, patients who reported early life trauma exhibited a superior antidepressant response to psychotherapy (with or without nefazodone) when compared with those treated with antidepressant alone (shown in Fig. 1A). Moreover, the advantage of the combination of pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy (relative to psychotherapy alone) was modest and did not attain statistical significance in the subgroup of patients with early life trauma. The superiority of psychotherapy (with or without nefazodone) for patients reporting early life trauma persisted when the analyses were controlled for gender, age, race, and depression severity at baseline. Fig. 1B reveals similar findings with remission of depression, the most stringent criterion for treatment response as the end point. For patients with chronic forms of depression and early life trauma who completed the study, remission was attained in 48.3% of the patients treated with CBASP, 32.9% treated with the antidepressant, and 53.9% treated with combination therapy. In these patients, but not in patients with chronic depression and no childhood trauma, the remission rate was significantly higher with psychotherapy compared to antidepressant treatment (Wald χ2=6.8912, df=1, P= 0.0087). The effect was confirmed when LOCF analysis was performed (Wald χ2=6.5315, df=1, P=0.0106). Based on the LOCF data, the likelihood of achieving remission in patients with chronic forms of major depression and any early adverse life event was estimated to be twice as high after treatment with psychotherapy when compared to antidepressant therapy (odds ratio=2.322, 95% confidence interval=1.225–4.066). Further analysis of type of early trauma indicates that this effect was particularly prominent in patients with chronic forms of depression and parental loss (odds ratio for remission after psychotherapy versus antidepressant=2.7857, 95% confidence interval=1.295–6.182).

Discussion

These findings have significant implications for research on the pathophysiology of chronic forms of major depression and for the treatment of chronic depression. The differential response of chronic depression to CBASP psychotherapy versus pharmacotherapy as a function of the presence of early life trauma suggests that there may be important differences in the etiology and pathogenesis of depression in individuals with and without history of early trauma. Taking this finding into account may reduce the often observed heterogeneity in biological studies of depressed patients. Indeed, we recently demonstrated that the widely replicated finding of reduced hippocampal volume in patients with major depression is largely due to the subgroup of patients with early life trauma (21). Future studies are needed to determine the generalizability of our findings. In particular, we examined only one form of psychotherapy and one antidepressant medication. It is important to compare the effectiveness of CBASP to cognitive-behavioral therapy, interpersonal therapy, and both long- and short-term psychodynamic psychotherapy in the treatment of patients with chronic forms of major depression and early life trauma to identify the elements of psychotherapy that are most critical to antidepressant response. It is also important to determine whether the relatively poor treatment response of patients with chronic depression and early life trauma to nefazodone alone is also true of other antidepressants, including the very commonly prescribed selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, e.g., paroxetine, sertraline, fluoxetine, escitalopram, and citalopram; dual serotonin/norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, e.g., venlafaxine, milnacipran, and duloxetine; or antidepressants that act by other mechanisms of action, e.g., mirtazepine and bupropion.

| Childhood Trauma Characteristic | Nefazodone (n=226) | Psychotherapy(n=228) | Nefazodone and Psychotherapy(n=227) | Statistics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parental loss ≤ age of 15 yr, % | 34.3 | 36.1 | 32.14 | χ2=0.77, df=2, NS |

| Physical abuse, % | 40.9 | 41.7 | 47.8 | χ2=2.56, df=2, NS |

| Sexual abuse, % | 15.0 | 15.3 | 18.8 | χ2=1.42, df=2, NS |

| Neglect, % | 11.8 | 7.9 | 10.3 | χ2=1.91, df=2, NS |

| Age at earliest loss, yr | 6.9±5.0 | 6.9±4.7 | 6.9±4.4 | F=0.00, df=2,220, NS |

| Age at earliest physical abuse, yr | 6.3±3.1 | 6.1±3.4 | 6.4±3.4 | F=0.13, df=2,201, NS |

| Age at earliest sexual abuse, yr | 9.3±3.2 | 8.4±3.0 | 8.5±3.6 | F=0.91, df=2,133, NS |

| Age at earliest neglect, yr | 6.7±4.0 | 7.3±4.2 | 6.6±4.1 | F=0.11, df=2,52, NS |

| Age at earliest trauma, yr | 6.1±4.0 | 6.4±4.1 | 6.0±3.9 | F=0.24, df=2,379, NS |

| Duration of physical abuse, yr | 7.5±4.1 | 7.3±5.6 | 7.9±5.3 | F=0.33, df=2,198, NS |

| Duration of sexual abuse, yr | 1.2±1.8 | 2.0±2.9 | 2.7±3.8 | F=2.43, df=2,127, NS |

| Duration of neglect, yr | 8.2±5.2 | 6.2±6.5 | 7.2±5.5 | F=0.61, df=2,52, NS |

| Duration of overall trauma, yr | 7.2±4.7 | 6.9±5.7 | 7.4±5.8 | F=0.19, df=2,279, NS |

| Childhood trauma severity, % | χ2=5.39, df=8, NS | |||

| No trauma | 38.4 | 36.1 | 32.1 | |

| One trauma type | 34.7 | 36.1 | 38.8 | |

| Two trauma types | 16.0 | 19.9 | 18.3 | |

| Three trauma types | 8.2 | 6.5 | 9.4 | |

| Four trauma types | 2.7 | 1.4 | 1.3 |

Figure 1. (A) Response to antidepressant (nefazodone), psychotherapy (CBASP), and the combination (nefazodone and CBASP) as a function of treatment type and early adverse life events in patients with chronic forms of major depression. In this completer analysis, the effect of the presence or absence of histories of childhood adversity (parental loss, physical abuse, sexual abuse, neglect) on HRSD24 scores was evaluated. A general linear model with two factors (treatment and childhood adverse experience) was computed. *, There was a significant interaction of effects of treatment type and parental loss (F=4.46, df=1,495, P=0.0121), physical abuse (F=3.25, df=1,495, P=0.03), neglect (F=4.82, df=1,495, P=0.0084), and any trauma (F=3.13, df=1,495, P=0.0446). The patients with any early life trauma responded well to psychotherapy alone or the combined treatment but not to antidepressant alone. Patients with chronic depression with early life trauma responded equally well to antidepressant and CBASP. (B) Remission rates as a function of treatment type and early adverse life events in patients with chronic forms of major depression. Remission was defined as HRSD24 score≥8. *, Completer analysis using logistic modeling revealed a significantly higher remission rate in the patients with chronic forms of major depression and early life trauma treated with psychotherapy compared to antidepressant treatment (Wald χ2=6.8912, df=1, P=0.0087). The effect was confirmed in the LOCF analysis (Wald χ2=6.5315, df=1, P=0.0106). The likelihood of achieving remission in patients with chronic forms of major depression and any early adverse life event was twice as high after treatment with psychotherapy when compared to antidepressant therapy (odds ratio=2.322, 95% confidence interval=1.225–4.066). Further analysis of type of early trauma indicates that this effect was particularly prominent in patients with chronic forms of depression and parental loss (odds ratio for remission after psychotherapy versus antidepressant=2.7857, 95% confidence interval=1.295–6.182).

1 Kessler, R. C., McGonagle, S., Zhao, C. B., Nelson, M., Hughes, S., Eshleman, S., Wittchen, H. U. & Kendler, K. S. (1994) Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 51, 8–19.Crossref, Google Scholar

2 Musselman, D. L., Evans, D. L. & Nemeroff, C. B. (1998) Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 55, 580–592.Crossref, Google Scholar

3 Nemeroff, C. B., Compton, M. T. & Berger, J. (2001) Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 932, 1–23.Crossref, Google Scholar

4 Hays, R. D., Wells, K. B., Sherbourne, C. D., Rogers, W. & Spritzer, K. (1995) Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 52, 11–19.Crossref, Google Scholar

5 Nemeroff, C. B. & Schatzberg, A. F. (2002) in A Guide to Treatments That Work, eds. Nathan, P. E. & Gorman, J. M. (Oxford Univ. Press, New York), pp. 229–261.Google Scholar

6 Hollon, S. D., Thase, M. E. & Markowitz, J. C. (2002) Psychol. Sci. Publ. Interest 3, 39–77.Crossref, Google Scholar

7 Rush, A. J. & Thase, M. E. (1998) in WPA Series: Evidence and Experience in Psychiatry, eds. Maj, M. & Sartorius, N. (Wiley, Chichester, U.K.), 2nd Ed., Vol. 1, pp. 161–206.Google Scholar

8 Keller, M. B., McCullough, J. P., Klein, D. N., Arnow, B., Dunner, D. L., Gelenberg, A. J., Markowitz, J. C., Nemeroff, C. B., Russell, J. M., Thase, M. E., et al. (2000) N. Engl. J. Med. 342, 1462–1470.Crossref, Google Scholar

9 Thase, M. E., Greenhouse, J. B., Frank, E., Reynolds, C. F., III, Pilkonis, P. A., Hurley, K., Grochocinski, V. & Kupfer, D. J. (1997) Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 54, 1009–1015.Crossref, Google Scholar

10 Esposito, K. & Goodnick, P. (2003) in The Psychiatric Clinics of North America–Drug Therapy: Predictors of Response, eds. Rosenbaum, J. F. & Dunner, D. L. (Saunders, Philadelphia), Vol. 26, pp. 353–366.Google Scholar

11 Rothschild, A. J. & Duval, S. E. (2003) J. Clin. Psychiatry 64, 390–396.Crossref, Google Scholar

12 American Psychiatric Association (1994) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (Am. Psych. Assoc., Washington, DC).Google Scholar

13 McCullough, J. P., Jr. (2000) Treatment for Chronic Depression: Cognitive Behavioral Analysis System of Psychotherapy (CBASP) (Guilford, New York).Google Scholar

14 Hirschfeld, R. M. & Goodwin, F. K. (1988) in Textbook of Psychiatry, eds. Hales, R. E. & Yudofsky, S. (Am. Psychiat. Press, Washington, DC), pp. 403–441.Google Scholar

15 Kendler, K. S., Kessler, R. C., Walters, E. E., MacLean, C., Neale, M. C., Heath, A. C. & Eaves, L. J. (1995) Am. J. Psychiatry 152, 833–842.Crossref, Google Scholar

16 Heim, C. M. & Nemeroff, C. B. (2001) Biol. Psychiatry 49, 1023–1039.Crossref, Google Scholar

17 Dube, S. R., Anda, R. F., Velitti, V. J., Chapman, D. P., Williamson, D. F. & Giles, W. H. (2001) J. Am. Med. Assoc. 286, 3089–3096.Crossref, Google Scholar

18 Kornstein, S. G., Schatzberg, A. F., Thase, M. E., Yonkers, K. A., McCullough, J. P., Keitner, G. I., Gelenberg, A. J., Davis, S. M., Harrison, W. M. & Keller, M. B. (2000) Am. J. Psychiatry 157, 1445–1452.Crossref, Google Scholar

19 Lizardi, H., Klein, D. N., Ouimette, P. C., Riso, L. P., Anderson, R. L. & Donaldson, S. K. (1995) J. Abnorm. Psychol. 104, 132–139.Crossref, Google Scholar

20 Thase, M. E., Entsuah, A. R. & Rudolph, R. L. (2001) Br. J. Psychiatry 178, 234–241.Crossref, Google Scholar

21 Vythilingam, M., Heim, C., Newport, D. J., Miller, A. H., Anderson, E., Bronen, R., Brummer, M., Staib, L., Vermetten, E., Charney, D. S., et al. (2002) Am. J. Psychiatry 159, 2072–2080.Crossref, Google Scholar