Treatment Recommendations for the Use of Antipsychotics for Aggressive Youth (TRAAY) Part II

Abstract

Objective: To develop treatment recommendations for the use of antipsychotic medications for children and adolescents with serious psychiatric disorders and externalizing behavior problems. Method: Using a combination of evidence- and consensus-based methodologies, recommendations were developed in six phases as informed by three primary sources of information: (1) current scientific evidence (published and unpublished), (2) the expressed needs for treatment-relevant information and guidance specified by clinicians in a series of focus groups, and (3) consensus of clinical and research experts derived from a formal survey and a consensus workshop. Results: Fourteen treatment recommendations on the use of atypical antipsychotics for aggression in youth with comorbid psychiatric conditions were developed. Each recommendation corresponds to one of the phases of care (evaluation, treatment, stabilization, and maintenance) and includes a brief clinical rationale that draws upon the available scientific evidence and consensus expert opinion derived from survey data and a consensus workshop. Conclusion: Until additional research from controlled trials becomes available, these evidence- and consensus-based treatment recommendations may be a useful approach to guide the use of antipsychotics in youth with aggression.

Antipsychotics are commonly prescribed to children and adolescents in inpatient and day treatment settings (Campbell et al., 1984, 1999). Epidemiological data show that antipsychotic prescribing rates for children and adolescents in a midwestern Medicaid population increased 63% from 1990 to 1996, primarily because of a substantial increase in the use of atypical antipsychotics (Malone et al., 1999). In Texas, Medicaid data from 1996 through 2000 indicate a 160% increase in prevalence over the 5-year period (Patel et al., 2002). This increased use of antipsychotics merits careful scrutiny because the risk of drug-related side effects, some of which are serious, is greater with antipsychotics than most other psychotropics used in children. Also of concern is the dearth of evidence to support current practices involving the use of antipsychotics to treat aggression in youth.

The Center for the Advancement of Children’s Mental Health at Columbia University has joined with the New York State Office of Mental Health (NYS-OMH) and leading experts across the United States to address the need for a synthesis of knowledge in this area. The result of this initiative is the development of the Treatment Recommendations for the Use of Antipsychotics for Aggressive Youth (TRAAY). The TRAAY are based on the available research and on prevailing expert consensus. In the companion article (Schur et al., 2003), we present findings from a literature review of the environmental and pharmacological treatments for children and adolescents with aggression. In this report, we combine this evidence from the literature review with expert consensus in the field to present recommendations for clinicians who provide intensive treatment to children and adolescents with aggression.

Aggression is often defined as any kind of behavior that has the potential (and often the intention) to damage an inanimate object or harm a living being (Volavka and Citrome, 1999). Here, we focus specifically on the treatment of impulsive aggression, as opposed to predatory aggression. This distinction is based on a body of evidence that indicates that predatory aggression is diagnostically distinct from impulsive aggression and warrants a different course of treatment. These recommendations are primarily applicable to patients with any type of physical or verbal aggression that is significant and frequent enough to interfere with the patients’ functioning. We also consider the frequent expression of any behavior, verbal or physical, that indicates the imminent potential for harm as indicating the need for possible pharmacological intervention.

Developing and evaluating treatments for aggression have been difficult because aggressive behaviors occur in such varied environmental and psychiatric contexts in children. Furthermore, standard clinical practices to manage aggression have been driven by increasing social and financial pressures to decrease rates of hospitalization, length of hospital stay, and incidence of physical restraints and seclusion, rather than by scientific evidence. Because of limited research in this area, much of the basis for interventions in aggressive youth has evolved out of heuristic clinical practices, the adult literature, and case reports. To address the gaps in our understanding and to develop the most scientifically driven, clinically relevant treatment recommendations, we began this project with a review of methods that have been used to develop practice guidelines.

The surge of interest in guidelines, algorithms, and recommendations has led to advances in the methods used to develop standardized treatments for use in clinical practice (Weiden and Dixon, 1999). Much of the seminal work in the area of guideline development has been the product of efforts to standardize treatment for schizophrenia. In the past 10 years, the American Psychiatric Association (APA) (APA, 1997), the Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT) (Lehman et al., 1998), the Expert Consensus Guidelines (McEvoy et al., 1999), and the Texas Medication Algorithm Project (TMAP) (Miller et al., 1999) have published different sets of treatment guidelines for schizophrenia. The APA, PORT, and TMAP are based on literature reviews, and while these guidelines focus on vastly different aspects of treatment (assessment, psychosocial, and psychopharmacological treatments, respectively), all address areas for which there is a substantial scientific evidence base. In contrast, the Expert Consensus Guidelines Series addresses pressing clinical issues for which research is lacking. The Expert Consensus Guidelines (McEvoy et al., 1999) are based on the statistical results of a survey of experts. Because of the use of different methodologies, the recommendations contained in each of these guidelines are complementary and can be used in tandem to guide treatment for people with schizophrenia.

To date, the development of treatment guidelines for children and adolescents with psychiatric disorders has lagged behind that of their adult counterparts. The general lack of clinical trials and outcome data for childhood and adolescent disorders may account for this overall lack of progress. Treatment guidelines based on literature review and consensus methods have been developed only for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) (Conners et al., 2001; Pliszka et al., 2000a,b) and major depressive disorder (Hughes et. al., 1999). The relative abundance of clinical trials data on ADHD may account for the progress seen in this specific domain of child and adolescent psychiatry. By contrast, the treatment recommendations presented here are unique because they do not focus on a specific diagnostic entity, but instead on aggressive youth who may present with a variety of disorders. Our target population is composed of patients who are excluded from most research; therefore, we have tailored our methods to utilize the evidence base (see Schur et al., 2003) along with a rigorous expert consensus process to address areas for which research is lacking. We outline this process below.

Method

The following treatment recommendations were created on the basis of a synthesis of expert consensus- and evidence-based research methodologies. We compiled the necessary information to develop these recommendations in seven phases:

| 1. | We conducted a series of 12 focus groups with physicians, treatment staff, and administrators at each of 12 NYS-OMH child and adolescent psychiatric facilities, to obtain information on issues pertaining to the treatment of the target population. The 12 facilities are primarily intermediate to long-term stay public psychiatric inpatient settings operated by NYS-OMH. Questions posed to physicians included the following, among others: “What obstacles or problems do you face with regard to assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with aggression?” “What tools, support, or assistance would help you with their diagnosis and treatment?” and “What treatment modalities or nonpharmacological interventions do you pursue before using antipsychotic medication?” (Pappadopulos et al., 2002). | ||||

| 2. | Using PsycINFO and Medline, we conducted an extensive literature review primarily from 1990 to 2001 on the treatment of aggression and the use of atypical antipsychotics in children and adolescents (see Schur et al., 2003). | ||||

| 3. | To answer questions not directly addressed in the literature, 18 research and 25 clinical experts (>10 years’ clinical and/or research experience with aggression or antipsychotic use in children) completed a 33-item survey on preferred prescribing practices in structured psychiatric settings for youth. The survey was adapted from the Expert Consensus Guidelines for behavioral disorders and mental retardation (Rush and Frances, 2000). Questions were framed in the context of common clinical vignettes of youth in inpatient settings, and physicians were asked to rate possible treatment alternatives on a commonly used 9-point Likert scale (9=extremely appropriate, 1=extremely inappropriate) developed by the RAND Corporation for obtaining expert consensus (Brook et al., 1986; Kahn et al., 1997). Responses were aggregated, and items demonstrating a high degree of consensus (mean>8.0) among respondents were considered potential candidates for best practice recommendations. Complete survey results are available from the corresponding author upon request. | ||||

| 4. | An Expert Consensus Workshop was held in March 2001 (participants are listed before the references) where a group of national experts (researchers as well as expert clinicians) on the use of antipsychotics in youth presented published and unpublished data and discussed candidate treatment recommendations derived from the survey data and literature review. The candidate treatment recommendations derived from step 3 guided the meeting’s discussion and consensus process. Follow-up consensus meetings along with additional review of the pertinent literature were used to further refine these recommendations. The final version of the recommendations presented here was the result of this intensive process. The last step of this process is described in item 6. | ||||

| 5. | To examine actual prescribing practices in the target facilities and to determine whether the proposed treatment recommendations would address existing practice needs, 100 closed patient charts were reviewed at three NYS-OMH child and adolescent inpatient facilities. Only patients (aged 10–18) who were prescribed antipsychotics and were hospitalized for less than 1 year were included; charts were reviewed for patients who were consecutively discharged from the hospital from the years 1999–2001. Cases were examined for treatment-specific information that mirrored the candidate best practices proposed by clinical and research experts. | ||||

| 6. | The data showed gaps between what survey responders considered preferred practices and actual practices used at the facilities. For example, although clinicians (n=25) and researchers (n=18) rated the treatment practice of systematically tracking treatment effects (i.e., by using rating scales) as extremely appropriate, evidence of systematically tracking treatment effects was not revealed in patient charts (0%) (Pappadopulos et al., 2002). In addition, clinicians and researchers strongly endorsed the systematic tracking of side effects, but this practice (except for tracking weight) was found in only 14% of the reviewed medical records. (For an extensive review of these findings see Pappadopulos et al., 2002.) | ||||

| 7. | Treatment recommendations were revised and finalized on the basis of feedback from the research and clinical experts participating in the Consensus Workshop. The results of this enterprise are presented below. | ||||

Results

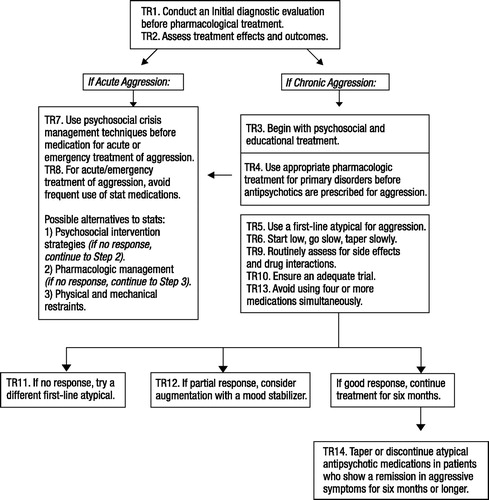

Based on the seven-step process, 14 treatment recommendations were developed to cover the different phases of treatment: evaluation, acute treatment, stabilization, and maintenance (Fig. 1). Each recommendation is composed of three parts: the recommendation itself, a brief explanation (italicized text), and a rationale that presents the empirical findings and experts’ consensus opinion. Current limits and gaps in the literature are also identified to help inform future research initiatives.

Disclaimer

While the following guidelines provide general suggestions for clinical practice, psychiatrists should use their own clinical judgment in treating each patient. As with all treatment decisions, clinicians must consider each patient’s unique clinical situation before following any treatment recommendations. As a result, these recommendations are not intended for use in litigation or insurance claims.

Recommendation 1: conduct an initial diagnostic evaluation before using pharmacological treatment

For all new cases, clinicians should conduct (or review the results of) comprehensive psychiatric diagnostic interviews with the patients and parent(s)/guardian(s) before prescribing, changing, or discontinuing medication.

Rationale: Before receiving any psychotropic medication, a child or adolescent should receive a comprehensive psychiatric evaluation. The literature on physician decision-making suggests that accurate diagnosis and treatment are positively correlated with the amount of “relevant” information available to the physician (Patel and Ramoni, 1997). In addition, manipulating the medication regimen before an adequate evaluation may make diagnosis more difficult. Children and adolescents admitted to controlled psychiatric settings (e.g., inpatient and day treatment) often present with a range of complex psychiatric symptoms that are difficult to diagnose and treat (Weller et al., 1999). Missing clinical information further complicates the situation. Thus, during the evaluation period, clinicians should make every effort to obtain previous treatment records, contact previous treating physicians, and/or acquire pharmacy prescription records with the guardian’s consent. Clinicians should use this information along with the diagnostic interview to develop a conceptual-etiological model and clinical formulation of the patient’s problems, and use these hypotheses to guide all interventions, including the use of medications. The evaluation should also include a physical examination and appropriate laboratory studies (e.g., electrocardiogram, complete blood cell count, glucose, lipids, other blood chemistry profiles, etc.). For parameters describing an extensive psychiatric evaluation, see the practice parameters on assessment published by the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP) (1997a).

Recommendation 2: assess treatment effects and outcomes

Standardized symptom and behavior rating scales with proven reliability and validity should be used to measure the severity and frequency of target symptoms before treatments are initiated, at regular intervals throughout treatment, during acute episodes, and when treatments are changed or discontinued.

Rationale: In treating aggression, clinicians should use accurate methods of assessment that take into account the frequency, duration, and severity of behavioral incidents (e.g., total number of and amount of time spent in restraints/seclusions/time-outs per week; seriousness of aggressive incidents). The systematic, routine tracking of target symptoms in severely disturbed youth with complex behavior problems holds the promise of optimizing treatments, since repeated use of tools such as standardized rating scales likely provides a highly accurate, systematic evaluation of treatment response over time. In addition, standardized ratings facilitate the operationalization of treatment responses and the development of systematic approaches to treatment, especially in the case of partial medication treatment responses (Rush, 2001). From the perspective of mental health treatment providers, the use of behavioral rating scales should allow for the development of a common language among multidisciplinary professionals. Finally, use of such scales allows the pooling of outcome data from several patients to better evaluate the effectiveness of specific treatments. For example, by using a scale such as the Modified Overt Aggression Scale, global weekly scores can be calculated and used to assess clinical outcomes and to inform treatment strategies both for individual patients and for cohorts of patients receiving similar treatments (Kay et al., 1988); scales are also available for parents to systematically track their children’s aggressive behavior (Halperin et al., 2002). Table 1 provides examples of symptom and behavior-rating scales that may be used with child and adolescent psychiatric inpatients.

To date, there is no generally accepted measure of aggression that is used in research or in clinical settings. While rating scales do provide a rigorous approach to the evaluation of aggressive behavior, no scale captures the full impact of aggressive symptoms on patient functioning. Clinical judgment is also needed to assess the degree to which a patient’s insulting, provocative, or threatening comments interfere with his or her vocational, academic, and social functioning, and whether pharmacological treatments are needed.

Recommendation 3: begin with psychosocial and educational treatment

Structured psychosocial and educational interventions should be the first line of treatment and should be continued even if subsequently medications are initiated to manage aggression.

Rationale: In the companion article (Schur et al., 2003), we discuss research indicating that psychosocial interventions may prevent overprescribing of medications, particularly antipsychotics, in inpatient and day treatment settings (also see Foxx, 1998). When psychotropic medications are necessary to treat disruptive behavior, they should be delivered as part of a comprehensive psychotherapeutic and educational program. An ideal therapeutic milieu should include contingency management programs, skills training programs, individualized interventions, and psychoeducational programs. For example, the NYS-OMH (1997) developed a comprehensive program to reduce the use of seclusion and restraint with hospitalized children and adolescents. The program emphasizes creating a therapeutic milieu that focuses on preventing aggressive behavior, and systematic training for staff is performed and maintained.

Recommendation 4: use appropriate treatment for primary disorders as a first-line treatment

Symptoms of aggression are common in a wide range of psychiatric conditions. Aggressive patients who also present with persistent and clinically significant symptoms of hyperactivity, anxiety, depression, or mania should receive at least one adequate trial of a first-line agent for these “primary” disorders.

| • | If a youth with current aggression also has severe and persistent hyperactivity or a verifiable personal history of ADHD, consider using a stimulant before using an antipsychotic. | ||||

| • | If a youth with current aggression also has anxious or depressive mood symptoms, consider using a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) antidepressant before using an antipsychotic. | ||||

| • | If a youth with current aggression either has manic symptoms or a verifiable family or personal history of bipolar disorder without current manic symptoms, consider using valproate or lithium before using an antipsychotic. | ||||

| • | If a youth with current aggression also has paranoid ideation, other perceptual aberrations, or clear psychotic symptoms, use an antipsychotic at appropriate doses to treat these symptoms before targeting aggression. | ||||

Rationale: Many nonpsychotic Axis I disorders are often associated with increased irritability, agitation, and aggression. If a primary disorder is identified (i.e., a disorder that antedates the onset of the aggressive symptoms and/or that also might be associated with aggressive symptoms), clinicians should focus treatment on the primary disorder before using pharmacological strategies to address the aggression as a target symptom. This is more likely to allow treatment with a single psychotropic agent, may be more effective, and may avoid significant side effects that are frequently associated with antipsychotic medications. AACAP has published practice parameters on the diagnosis and treatment of many primary disorders, including anxiety disorders (AACAP, 1997b), ADHD (AACAP, 2002b), bipolar disorder (AACAP, 1997c), depressive disorder (AACAP, 1998), and schizophrenia (McClellan and Werry, 1994).

For several reasons, physicians should give preference to monotherapy medication approaches in treating children and adolescents. Monotherapy is simple, allowing physicians to assess treatment response and side effects of each trial of medication. In addition, monotherapy may improve patient and family treatment adherence by decreasing the complexity of the treatment regimen. Finally, acute episodes and periods of symptom exacerbation may be easier to treat when monotherapeutic strategies are used (Weiden and Casey, 1999). However, high-dose therapy should not be used simply to keep a patient on monotherapy. Monotherapy with other agents should address specific target symptoms that might lead to a reduction in aggression.

Specific classes of psychotropic medications have been identified as appropriate treatments for primary psychiatric disorders in youth. The treatment of these primary disorders may reduce comorbid aggression. For example, numerous studies have demonstrated the efficacy of stimulants in the treatment of ADHD (Greenhill and Ford, 2002). A recent meta-analysis of 28 of these studies revealed that stimulants have an overall weighted mean effect size of 0.84 for overt and 0.69 for covert aggression-related behaviors in ADHD (Connor et al., 2002). At least two studies (Klein and Abikoff, 1997; MTA Cooperative Group, 1999) have shown that stimulants may be more effective in reducing both core ADHD symptoms and oppositional-aggressive symptoms than psychosocial treatments alone.

Although more data are needed, the use of SSRIs in children and adolescents has been shown to be effective in treating depression (e.g., Keller et al., 2001). SSRIs have also been found to be effective in reducing anxiety symptoms in youth with obsessive-compulsive disorder (e.g., Riddle et al., 2001—fluvoxamine in 120 youth) and a variety of other anxiety disorders (e.g., Pine et al., 2001). In addition, SSRIs are generally regarded as first-line treatments for posttraumatic stress disorder in youth (reviewed by Perrin et al., 2000) and panic disorder (Renaud et al., 1999).

Lithium and valproic acid are considered primary treatments for bipolar disorder (AACAP, 1997c). Several studies show lithium and valproate’s efficacy in normalizing mood symptoms in youth with bipolar disorder (Geller et al., 1998; Kowatch et al., 2000; Ryan et al., 1999; Strober, 1997; West et al., 1995). Recently, concerns about the misdiagnosis of early-onset bipolar disorder have received increasing attention in child psychiatry. When children and adolescents present with irritability, mood instability, and aggression, clinicians should carefully evaluate the possibility of early-onset bipolar disorder as the primary diagnosis.

A growing body of evidence indicates that atypical antipsychotics are effective first-line treatments for psychotic disorders in youth, including childhood-onset schizophrenia and first-episode schizophrenia (Kumra et al., 1996; Sikich, 2001). Research on aggression in psychotic adults suggests that aggressive incidents decrease when hallucinations and delusions are minimized with medication (Citrome and Volavka, 2000). (See recommendation 5 for an explanation of side effects associated with atypical agents.)

The principle of treating primary disorders to reduce their impact on presumed secondary problems (such as aggression) might be a hoped-for ideal for every patient. However, clinical experience indicates that the severity and frequency of aggressive symptoms often necessitate the simultaneous use of antipsychotic medications along with first-line treatments for the primary conditions (Kafantaris, 1995; Kafantaris et al., 1998).

Recommendation 5: use an atypical antipsychotic first rather than a typical antipsychotic to treat aggression

When psychosocial and first-line medication treatments for primary nonpsychotic conditions have failed, physicians initially should use first-line atypical (rather than typical) antipsychotic medications to treat severe and persistent aggression.

Rationale: Treatment history and risk assessments for the severity and frequency of aggressive acts should help determine the need for antipsychotic medications. First-line atypical antipsychotics (i.e., risperidone, olanzapine, quetiapine, ziprasidone) should be used initially because they have a safer acute side effect profile than the traditional antipsychotics, i.e., likely lower risk for tardive dyskinesias, neuroleptic malignant syndrome, cognitive impairment, and extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS) (e.g., see Campbell et al., 1997; Gillberg, 2000; Richardson et al., 1991). Currently there is insufficient evidence regarding potential negative long-term consequences of the weight gain and endocrinological changes associated with most atypical antipsychotics to negate their acute advantages over traditional antipsychotics. However, this is clearly an area that requires further research and evaluation. For a discussion of the literature, see Schur et al. (2003).

The companion article (Schur et al., 2003) reviewed the relatively small but growing body of evidence supporting the atypical antipsychotics’ efficacy in treating aggression in youth. No data are available regarding the relative superiority of one atypical antipsychotic over another for aggressive behavior. However, the choice of a particular atypical antipsychotic medication should be made based on patient/guardian acceptability, comorbid general medical conditions, prior individual drug response, side effect profile, and long-term treatment planning. In addition, while short-term data on atypical agents support their efficacy and safety, few data are available on the chronic use of these agents in youth. Clinicians and researchers express caution about the long-term health risks associated with atypical antipsychotic-induced weight gain. Table 2 summarizes the available literature on the side effect risks associated with atypical antipsychotic medication.

Recommendation 6: use a conservative dosing strategy

Physicians should use a “start low, go slow, taper slow” dosing strategy when using antipsychotic medications to treat aggression in children and adolescents.

Rationale: “Start low, go slow, taper slow” dosing strategies are especially important for youth being tried on atypical antipsychotic agents. Children and adolescents usually require lower doses of antipsychotics than adults to achieve a therapeutic response, although this issue needs further investigation (for exceptions see Campbell et al., 1999). Before an atypical antipsychotic is considered “ineffective” for aggression in a child or adolescent, it should be tried for a minimum of 2 weeks at an appropriate dose (Findling et al., 2000). Findings suggest that atypical agents should be tapered slowly before being discontinued and that clinicians should monitor for signs of withdrawal dys-kinesia (Lore, 2000; Perry et al., 1997; Rowan and Malone, 1997). Table 3 offers suggestions regarding medication-specific starting doses, titration schedules, and recommended daily dose ranges.

Recommendation 7: use psychosocial crisis management techniques before medication for acute or emergency treatment of aggression

For acute episodes involving severely disruptive behaviors, physicians and staff should use psychosocial crisis intervention strategies before resorting to the emergency use of medications to control behavior. When behavioral interventions have failed to control agitated and aggressive behaviors, the choice to use emergency—“stat” or “p.r.n.”—pharmacological management should correspond to the risk for potential injury. Finally, physical and mechanical restraints and locked seclusion should be used only when all other approaches have failed.

Rationale: Aggressive acts are often preceded by a period of escalating agitation. Psychosocial interventions to help patients regain self-control during this period can help avoid the need for chemical and physical restraints. Studies show that the incidence of seclusion and restraint declines significantly when staff members are trained to minimize the potential for aggression (Foxx, 1998). Accordingly, psychiatric settings should develop crisis intervention procedures that are sensitive to the needs of their clinical populations and staff. Nursing staff input and support are essential because they are primarily responsible for maintaining unit safety (Fishel et al., 1994).

When youth exhibit early warning signs of aggression (e.g., intimidating/provocative behavior, escalating agitation), staff members should have available a range of intervention options to prevent or lessen the likelihood of escalating aggression. For example, behavioral strategies used in the NYS-OMH programs (NYS-OMH, 1997) include cueing or prompting, verbal warnings, verbal interventions, quiet time (time away), and time out from reinforcement (time-out). Staff can also consider offering youth a psychotropic medication on a “stat” or “p.r.n.” basis to assist them in maintaining control before aggression reaches a dangerous level. The goal should be maintaining the patient in the least restrictive environment possible and minimizing psychological and medical risks and consequences. For further information, readers are encouraged to refer to the AACAP practice parameter for the prevention and management of aggressive behavior with special reference to seclusion and restraint (2002a).

Recommendation 8: avoid frequent use of emergency (stat, p.r.n.) medications to control behavior

When antipsychotic “p.r.n.” or “stat” medications are used several times per day to manage agitation and/or aggression, physicians and treatment teams should reevaluate the diagnosis and the adequacy of behavioral and environmental interventions and then readjust the treatment plan and medication regimen. In most cases, physicians should consider using standing antipsychotic medications rather than frequent stat medications to treat aggression.

Rationale: The emergency use of medication to control behavior should not be considered a standard treatment for inpatient children and adolescents who manifest aggressive and disruptive behaviors. Studies examining prescribing trends on inpatient psychiatric settings reveal that diphenhydramine and antipsychotic medications are given in high proportions on a stat or p.r.n. basis to patients already receiving standing antipsychotics (Kaplan and Busner, 1997; Singh et al., 1999). However, there is little evidence for the effectiveness of most of the commonly used acute pharmacological management techniques for aggressive behaviors (Measham, 1995). Vitiello and colleagues (1991) found that intramuscular (IM) injections reduced aggressive and disruptive behavior regardless of whether active medication or placebo was administered, suggesting that factors other than the medication itself acted to reduce aggression. In addition, many medications, particularly traditional antipsychotics, have more severe potential side effects when administered IM than when administered orally (e.g., hypotension with chlorpromazine or acute dystonia with haloperidol). With the recent introduction of IM olanzapine and ziprasidone, the use of IM typical antipsychotics for acute aggression may be on the decline. While the use of IM atypical agents for acute aggression holds some promise for use in children, supportive data and clinical experience are lacking. To date, only two published studies demonstrate the safety and efficacy of these agents in adults (Daniel et al., 2001, for IM ziprasidone; Meehan et al., 2001, for IM olanzapine). Until more research is available, it is premature to comment on the use of IM atypical antipsychotics to treat emergency aggression in children. Despite the limited data available to support the use of stat and p.r.n. medications, they remain an important and commonly used clinical treatment by physicians on inpatient and day hospital settings. When emergency medications appear indicated, physicians should be aware of a patient’s current medications as well as the possibility that the patient is using illicit drugs and the potential for drug interactions. Side effects associated with standing antipsychotic medications, particularly EPS and cardiovascular side effects, can also occur with intermittent use of antipsychotics. Consequently, inpatient youth who are given emergency medications must be monitored closely for adverse drug responses and interactions (see below).

Because many patients who receive emergency and/or p.r.n. medications are already receiving standing antipsychotics (Kaplan and Busner, 1997), clinicians should consider optimizing the standing antipsychotic to control persistent aggression rather than using emergency medications. If frequent p.r.n. medications have been required, it may also be useful to transiently use standing sedating agents (diphenhydramine or hydroxyzine), while gradually increasing the standing dose of atypical antipsychotic or using a more sedating atypical agent. When a reasonable dose of an atypical antipsychotic is reached, the sedating agent can be gradually tapered. To prevent the misuse and overuse of emergency medications, clinicians should qualify their orders by setting a maximum number of “stat” doses per day, an expiration date on all p.r.n. orders, and a clear definition of which behaviors warrant the use of stat and p.r.n. medications. Research is needed to determine the effect of emergency medication interventions on outcome compared with other treatment alternatives.

Strategies for acute pharmacotherapy of aggression may include the following: (1) Always offer the patient an oral p.r.n. medication before IM administration is used. (2) When all oral medications are refused or cannot be given, IM administration may be necessary. IM administration should be used only for extremely severe cases. (3) When “cheeking” of medication is suspected, use quick-dissolving olanzapine (Zydis) or liquid risperidone at the same doses as p.o. (4) Avoid using three consecutive stat administrations of a medication during a 24-hour period.

Recommendation 9: assess side effects routinely and systematically

Medication side effects and adverse drug interactions should be monitored routinely and systematically.

Rationale: The companion article (Schur et al., 2003) describes the results of research studies and case reports indicating that antipsychotics are associated with a range of side effects (e.g., EPS, tardive dyskinesias, akathisia, cardiovascular changes, weight gain, and diabetes), some of which can be fatal (e.g., agranulocytosis, neuroleptic malignant syndrome). An overview of these findings is provided in Table 2. Given the limited short-term safety and efficacy data in youth and even scarcer long-term data, clinicians should be very vigilant in evaluating side effects by monitoring vital signs and weight, obtaining a thorough review of systems, and a doing a targeted physical examination that includes assessments for EPS, cardiac function, and prolactin-associated phenomena such as gynecomastia, galactorrhea, and amenorrhea (Remschmidt et al., 2000; Sallee et al., 2000; Wudarsky et al., 1999). Assessment of EPS and dyskinesia is likely to be facilitated by using reliable and valid rating scales such as the Neurologic Rating Scale (Simpson and Angus, 1970) and the Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale (National Institute of Mental Health, 1985) at baseline and periodically throughout treatment. Laboratory studies to monitor potential changes in liver function and glucose metabolism (HgbA1c) should also be considered at regular intervals. It is also important to monitor for signs and symptoms of hyperprolactinemia and to intervene if it is present. In an epidemiological study in adults, Ray et al. (2001) found an increased risk of cardiac events with all typical antipsychotics. It is likely that atypical antipsychotics pose the same risk. To screen for congenital cardiac conduction delays, it is prudent to obtain electrocardiograms in all children before starting an antipsychotic, with dose increases and at regular intervals (Reilly et al., 2000; Sallee et al., 2000). Inasmuch as many adverse events appear to be dose-related, it is important to use the lowest possible therapeutic dose of any medication. Finally, it is important to monitor the other medications and substances the subject may be using, as many agents can alter the metabolism of atypical antipsychotics or exacerbate their potential side effects (Table 4).

Several atypical antipsychotics have been associated with significant weight gain in adults and children (Armenteros et al., 1997; Wirshing et al., 1999). Findings from the adult literature and case reports suggest that weight gain leads to increased risk for diabetes, hypertension, and hypercholesterolemia (Blackburn, 2000). Before initiating atypical antipsychotics, physicians should advise families of the potential for weight gain and the importance of proper nutrition and exercise. Body weight should be monitored routinely, and the body mass index (BMI) (weight in kg/height in m2) should be calculated and plotted on a developmentally normed growth chart which may be found at the Centers for Disease Control Web site (www.cdc.gov/growthcharts). Antipsychotic-induced weight gain that exceeds the 97th percentile BMI for age in youth who were not initially obese or that exceeds 5 BMI units in youth who began treatment above the 97th percentile warrants consideration of adjunctive weight management interventions and the regular monitoring of serum glucose and lipid levels (Kumra et al., 1997; Szigethy et al., 1999). If weight gain continues, physicians should consider tapering or discontinuing the medications.

While atypical antipsychotics are considered less likely to cause EPS, akathisia, and dyskinesias than conventional antipsychotics, these side effects still occur and must be tracked (Lewis, 1998). For example, risperidone appears to lose its “atypicality” with regard to EPS and other side effects at higher doses (>6 mg for adults), which is likely to reflect higher dopamine D2 occupancy (Kapur and Seeman, 2001). If EPS are identified, antipsychotic dose reduction or concurrent use of anticholinergics for dystonia and parkinsonism or propanolol for akathisia should be considered. However, the lowest dose of anticholinergic possible should be used to minimize potential cognitive side effects.

Recommendation 10: ensure an adequate trial before changing medications

Before switching, augmenting, combining, or discontinuing medications because of a lack of or partial response, physicians should ensure that patients have received adequate trials of medication as well as psychosocial interventions.

Rationale: Before determining that a medication change is needed, physicians should ensure that medications have been administered at an appropriate dose and duration (Kafantaris et al., 1998) and that adequate and appropriate psychosocial interventions have been implemented. The parameters of an adequate trial vary according to the disorder being treated and the type of medication being administered. When atypical antipsychotics are prescribed for aggressive behavior, physicians should wait for a minimum of 2 weeks at therapeutic dose to determine whether the trial has been effective (Findling et al., 2000). For other disorders, several weeks may be needed to achieve a full therapeutic effect (Kumra et al., 1997).

To evaluate treatment response, target symptoms should be clearly delineated and monitoring parameters (e.g., rating scales) should be used. Physicians should consider using liquid risperidone or quick-dissolving olanzapine (Zydis) for patients suspected of “cheeking” medication or who have trouble swallowing pills. In addition, quick-dissolving olanzapine (Zydis) may have a relatively rapid onset of action and may be helpful for patients who are not responding to olanzapine in the pill form. For all medications, physicians should consider whether side effects such as akathisia or adverse drug interactions are causing or exacerbating symptoms (Table 4).

Recommendation 11: use a different atypical antipsychotic after a failure to respond to an adequate trial of the initial first-line atypical

If patients fail to respond to an adequate trial (dose and duration) of an initial atypical antipsychotic, physicians should first reassess the diagnosis and adequacy of behavioral interventions and, where appropriate, should administer a different atypical antipsychotic. In other words, for patients who continue to be dangerous or assaultive while on their first atypical antipsychotic, and whose behavior is not due to inadequately treated ADHD, anxiety, depression, or mania, monotherapy with a different atypical antipsychotic should be tried.

Rationale: Since there is little evidence for the superiority of any one atypical antipsychotic in the treatment of aggression, patients and their families should be offered a second trial of a different atypical antipsychotic if the first has failed. When patients fail to respond to two adequate trials of atypical antipsychotics, physicians should consider using a mood stabilizer or typical antipsychotic. Physicians should consider using multiple agents in combination only after at least two adequate trials of first-line medications have failed. For treatment-resistant patients who have failed three or more adequate trials of first-line or second-line interventions, consider a trial of clozapine.

Recommendation 12: consider adding a mood stabilizer after a partial response to an initial first-line antipsychotic

When patients respond only partially to an initial first-line atypical antipsychotic medication (i.e., symptoms decrease but do not remit), physicians should first reassess the diagnosis, the adequacy of behavioral interventions, pharmacotherapy for any identified primary disorder, and the adequacy of the medication trial (i.e., duration and dose). Then, when appropriate, they should consider adding a mood stabilizer.

Rationale: Information on combinations of atypical antipsychotics and mood stabilizers is limited to adult studies and case reports. Case reports in adults indicate that risperidone may be effective and safe when used as an adjunct to valproic acid in treating psychosis and agitation (e.g., Waring et al., 1999). Despite the lack of research on combination pharmacological strategies in children and adolescents, results of a survey of preferred medication-prescribing practices for inpatient and day hospital youth reveal a high degree of consensus among child and adolescent psychiatrists. Notably, survey responders (18 of 19 researchers and 24 of 25 full-time inpatient clinicians) endorsed adding a mood stabilizer when there has been a partial response to an adequate trial of an atypical antipsychotic prescribed for aggression (Pappadopulos et al., 2002).

Because of the harmful potential side effects of typical antipsychotics, mood stabilizers may be preferable as adjunctive medications when patients show a partial response to an initial first-line antipsychotic. This is particularly important because children may be more sensitive than adults to combined medications and their side effects (Woolston, 1999). Thus any adverse events that may be due to prescribed medications, especially combination pharmacotherapy, should be investigated (Baldessarini and Teicher, 1995; Kane and Marder, 1993). Medication combinations that may be problematic and result in side effects that can be misinterpreted as aggression are noted in Table 4.

Recommendation 13: if a patient is not responding to multiple medications, consider tapering one or more medication(s)

If patients have not shown meaningful responses to multiple psychotropic medications administered in combination, physicians should reexamine the diagnoses and the adequacy of behavioral interventions and consider tapering and discontinuing one or more medication(s).

Rationale: Physicians should reevaluate the medication regimens of patients who fail to show a beneficial response (i.e., decreased aggression) despite being on multiple medications. Physicians should begin with reevaluating the diagnosis and biobehavioral hypothesis for treatment. Then physicians should strategically discontinue or taper one or more medication(s), keeping in mind that the following medications are possible candidates for discontinuation:

In general, tapering and discontinuing medications are completed optimally in small increments over a 2- to 4-week period.

Although there are few well-controlled trials to guide the use of multiple psychotropic medications in youth, there are situations in which it is considered clearly appropriate. Multiple mood stabilizers can be beneficial for bipolar disorder. In addition, patients receive multiple medications during cross-tapering periods and for comorbid disorders. Nevertheless, combining medications may complicate treatment by increasing the risk for adverse events and drug interactions, obscuring treatment effects, and making adherence to medications more difficult. Given the potential negative consequences and limited evidence, multiple psychotropic medications should be used only after monotherapeutic approaches have proven insufficient. In advance of initiating multiple psychotropic medications, the goals of treatment, monitoring parameters, and time period for evaluation of medication response should be evaluated. Patients who do not show a meaningful response after an adequate trial should have one or more medications tapered and discontinued.

A medication-free period or “washout” may also be considered for cases in which the combination medication regimen may be obscuring the diagnosis and optimal course of treatment. For example, after a 4-week washout period, 23% of pediatric patients thought to have treatment-refractory schizophrenia were diagnosed with different disorders based on the lack of schizophrenia symptoms. For eight patients the washout period was curtailed because of the rapid and severe emergence of psychotic symptoms (Kumra et al., 1999). Although washout periods may not be feasible in settings with limited staff resources or brief lengths of stay, they should be considered for particularly complex cases.

Recommendation 14: taper and consider discontinuing antipsychotics in patients who show a remission in aggressive symptoms for six months or longer

Physicians should consider tapering atypical antipsychotic medications in patients who show a remission in aggressive symptoms for 6 months or longer. If patients tolerate the tapering of dose, the antipsychotic medication should be discontinued.

Rationale: Physicians should seriously consider tapering antipsychotic medications in patients who are no longer aggressive and who have shown no evidence of the potential for aggression within a 6- to 9-month period. However, the presence of an underlying psychotic disorder or a clear history of recurrent relapse or treatment-resistant symptoms generally precludes discontinuation of antipsychotics (Robinson et al., 1999). In addition, physicians must be cautious about discontinuing antipsychotics in patients with a history of life-threatening aggression. When tapering or discontinuing medications, physicians should reduce the dose by half and evaluate for symptoms and withdrawal-related side effects over a period of at least 2 weeks before making any further changes. It is particularly important to taper slowly among patients with mental retardation due to reported rebound effects (Baumeister et al., 1998).

Discussion

The TRAAY are the result of a unique collaborative initiative involving the Center for the Advancement of Children’s Mental Health at Columbia University, NYS-OMH, and academic and clinical experts across the United States. The TRAAY were developed (1) to provide a systematic treatment guide for the management of aggressive symptoms in youth treated in structured psychiatric settings and (2) to address concerns about the use and potential misuse of antipsychotic agents for aggressive behavior. The scientific support for these recommendations is reviewed in the companion article (Schur et al., 2003).

The TRAAY describe a standardized approach to the use of atypical antipsychotics for aggressive symptoms on inpatient and day hospital settings. Unlike most treatment guidelines that focus on specific diagnoses, these recommendations concentrate on a population of youngsters with comorbid conditions who are treated in structured psychiatric settings but who are excluded from most clinical research. To address current concerns among clinicians, candidate treatment domains that could benefit from standardization were identified through a review of patient charts, focus groups, NYS-OMH pharmacy databases, and the literature. An additional major strength of the TRAAY is the combined use of the evidence, expert consensus, and survey data to inform the development of each recommendation. To our knowledge, no other set of treatment recommendations has used this combination of methodologies to address important clinical questions not answered in the literature. In addition, because we included clinicians in our expert panel, the TRAAY are also sensitive to patient, staff, and administrative issues often encountered when treating youth in structured psychiatric settings. We believe that this combined approach gives these recommendations a high degree of credibility and feasibility.

Limitations

At this point, there is no evidence to suggest that the use of the TRAAY will necessarily improve treatment outcomes in youth with aggressive symptoms. Future studies should address issues within the recommendations (e.g., the efficacy of atypical antipsychotics versus mood stabilizers as first-line treatments). Research is needed to determine whether the consistent application of these recommendations will reduce the variability in treatment practices currently seen in prescribing trends across psychiatric facilities for youngsters. Studies on how best to help physicians adhere to recommendations are also needed. Another concern is that the application of the TRAAY may result in unintended increases in treatment costs by potentially lengthening hospital stays, increasing needs for direct care staff, or encouraging the use of more expensive but (it is hoped) safer medications. Only additional research can address these important issues. Our investigation of the charts of former patients at facilities where clinicians also completed the survey revealed that physicians did not always act in accordance with what they themselves identified as preferred treatment practices (Pappadopulos et al., 2002). It appears that the knowledge of what is clinically optimal is not necessarily consistently translated into practice behavior. As a result, we recognize that distributing these recommendations as a sole strategy will not necessarily change physician prescribing practices. Organizational factors can be important in determining whether a guideline can be implemented effectively, and one should also examine organizational factors and processes in attempting to implement treatment guidelines (Rosenheck, 2001).

In addition, while we were encouraged by the high degree of consensus among clinicians and researchers (the survey results are available upon request from the corresponding author), consensus is not a substitute for the scientific method of controlled experimentation and replication. As more data become available, we may find that some or all of these recommendations may need revision based on new findings. As a result, we advise clinicians to rely also on their own informed clinical judgment and to use these treatment recommendations only as a guide.

Future renditions of the TRAAY can be potentially improved by further detailing potential environmental causes of and specific psychosocial treatments for aggression, as well as by examining ways to assist physicians in applying such guidelines in their own treatment practices. A supplementary “Parent Guide” is currently in revision that uses input from consumer groups, parents, and patients themselves to make these recommendations more relevant and applicable to the needs of patients and families. It is also desirable to create partnerships with consumer groups at every step in the process of developing treatment recommendations, although this is difficult to accomplish because consumers, researchers, and administrators often have competing goals that may be difficult to reconcile. Giving key stakeholders leadership roles and voting rights in decisionmaking processes regarding specific recommendations is one method to ensure the active participation of all parties.

Clinical implications

The TRAAY were developed for use with the specific target symptom of aggression. The TRAAY are intended to be used as a systematic approach to treating youth with complex comorbid conditions and aggression. However, to avoid the risk of “chasing symptoms” rather than treating the primary disorder, these recommendations should not be used in isolation. As indicated in the TRAAY, all decisions must be guided by a biobehavioral hypothesis that is revised as new information about the patient’s response to different agents is revealed. Figure 1 illustrates how the TRAAY operate in tandem to guide ongoing treatment decisions when youth present with aggression.

It should be recognized that symptoms of aggression and hyperactivity may occur with several different diagnoses, including severe ADHD, severe oppositional defiant disorder, conduct disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, or bipolar disorder (mania), each of which may require a unique treatment approach. Some evidence suggests that there may be discrete subtypes of aggression that respond differentially to treatment. For example, lithium may be more efficacious in treating youngsters with conduct disorder and “explosive” aggression (Campbell et al., 1992; Malone and Simpson, 1998), while “predatory” aggression (Vitiello et al., 1990) may be less responsive to pharmacotherapy. To date, relatively few studies address the issue of subtyping comorbid aggression into clinically meaningful categories (e.g., see Vitiello et al., 1990), and this is an area that deserves further attention.

By way of caution, these recommendations and the expert panel’s opinions about these agents are based on data from relatively few controlled trials. The companion article (Schur et al., 2003) describes the gaps in the current evidence base, including the need for research regarding the impact of side effects on the overall health of developing children. Nonetheless, the TRAAY are intended as a starting point for best clinical practices that can be empirically evaluated and modified as new data become available. We note, however, that clinical trials cannot answer all possible treatment questions that arise when working with patients, so consensus methods must also continue to be used to meet clinicians’ ongoing needs for information. The TRAAY have been developed to provide clinicians with a preliminary framework to guide the use of antipsychotics in children and adolescents with aggression.

| Measure | Description | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anchored Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale-C-9 (BPRS-C-9; Hughes, unpublished) |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale–Children (BPRS-C; published in Overall & Pfefferbaum, 1982) |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL; Achenbach, 1991; available at http://www.aseba.org/index.html) |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Child Behavior Rating Form (CBRF; published in Edelbrock, 1985) |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Children’s Aggression Scale–Parent Version (CAS-P; Halperin et al., 2002). For a copy of the CAS-P contact Dr. Halperin, Psychology Department, Queen’s College, 65-30 Kissena Blvd., Flushing, NY 11367 |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Children’s Global Assessment Scale (C-GAS; Shaffer et al., 1983) |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Modified Overt Aggression Scale (MOAS; published in Kay et al., 1988) |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pediatric Inpatient Behavior Scale (PIBS; Kronenberger et al., 1997). For a copy of the PIBS contact Dr. Kronenberger, Riley Child and Adolescent, Psychiatry Clinic, 702 Barnhill Drive, Indianapolis, IN 46202 |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Severity and Acuity of Psychiatric Illness Scales (SAPIS; Lyons, 1998; available at http://www.parinc.com/) |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Antipsychotic Medication | Weight Gain | EPSa | Increase QTc Interval | Sedation | Anti-cholinergic | Prolactin | Orthostasis | Special Alertsb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risperidone | ++ | ++ | + | + | + | +++ | ++ | |

| Olanzapine | +++ | + | + | +++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | |

| Quetiapine | ++ | + | + | ++ | + | + | ++ | CC |

| Ziprasidone | 0 | + | ++ | + | + | + | + | |

| Clozapine | ++++ | 0 | + | ++++ | ++++ | ++ | ++++ | SZ,AG,CV |

| Usual Daily Dose Range for Aggressiona | Usual Daily Dose Range for Psychosis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atypical Antipsychotics | Starting Daily Dose | Titration Dose ↑ q3–4 Day (~Min. Days to Antipsychotic Dose) | Child | Adolescent | Child | Adolescent |

| Clozapine | 6.25–25 mg | 1–2 × starting dose (18–20) | 150–300 mg | 200–600 mg | 150–300 mg | 200–600 mgb |

| Olanzapine | 2.5 mg for children 2.5–5 mg for adolescents | 2.5 mg (9–16) | No data available | No data available | 7.5–12.5 mg | 12.5–20 mg |

| Quetiapine | 12.5 mg for children 25 mg for adolescents | 25–50 mg to 150 mg, then 50–100 mg (18–33) | No data available | No data available | No data | 300–600 mg |

| Risperidone | 0.25 mg for children 0.50 mg for adolescents | 0.5–1 mg (18–20 days) | 1.5–2 mg | 2–4 mg | 3–4 mg | 3–6 mg |

| Ziprasidone | 10 mg for children 20 mg for adolescents | 10–20 mg available | No data available | No data available | No data available | No data, in adults, 160–180 mg |

| Substance | Clinical Effect | Atypical Antipsychotic Interaction |

|---|---|---|

| Amphetamines, anorexiants | May exacerbate psychosis and agitation | Increased risk for withdrawal dyskinesia |

| Anticholinergics | Increased agitation, cognitive impairment | Diminished antipsychotic effect; additive anticholinergic effect |

| Fluoxetine (SSRI) | May increase agitation, EPS, akathisia | Possible decreased metabolism of risperidone and olanzapine; increased risk of EPS |

| Sertraline (SSRI) | May increase agitation, EPS, akathisia | Possible decreased metabolism of risperidone and quetiapine; increased risk of EPS |

| Fluvoxamine (SSRI) | May increase agitation, EPS, akathisia; seizures with clozapine | Possible decreased metabolism of olanzapine and clozapine |

| β-blockers | Exacerbated hypotension | |

| Benzodiazepines | May cause paradoxical agitation due to disinhibition | Exacerbated sedation |

| Caffeine | Anxiety/agitation | Possible diminished antipsychotic effect; muscle twitching |

| Cigarette smoking | Decreased; antipsychotic effect | Up to 50% reduction in antipsychotic concentrations |

| Clonidine | Hypotension; postural intolerance | |

| Ethanol | Decreased impulse control | |

| Lithium | Neurotoxicity (rare) | |

| Valproic acid | Atypicals may increase valproic acid levels associated with neurotoxicity |

Figure 1. Flow Chart Depicting the Systematic Application of the Treatment Recommendations for the Use of Antipsychotics for Aggressive Youth (TRAAY).

Achenbach TM (1991), Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist/4–18 and 1991 Profile. Burlington: University of Vermont Department of PsychiatryGoogle Scholar

American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (1997a), Practice parameters for the psychiatric assessment of children and adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 36(10 suppl):4S–20SCrossref, Google Scholar

American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (1997b), Practice parameters for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with anxiety disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 36(10 suppl):69S–84SCrossref, Google Scholar

American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (1997c), Practice parameters for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with bipolar disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 36(10 suppl):157S–176SCrossref, Google Scholar

American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (1998), Practice parameters for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with depressive disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 37(10 suppl):63S–83SCrossref, Google Scholar

American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (2002a), Practice parameter for the prevention and management of aggressive behavior in child and adolescent psychiatric institutions, with special reference to seclusion and restraint. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 41(2 suppl):4S–25SCrossref, Google Scholar

American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (2002b), Practice parameter for the use of stimulant medications in the treatment of children, adolescents, and adults. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 41(2 suppl):26S–49SCrossref, Google Scholar

American Psychiatric Association (1997), Practice guidelines for the treatment of patients with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 154(suppl 4):1–63Google Scholar

Armenteros JL, Whitaker AM, Welikson M, Stedge DJ, Gorman J (1997), Risperidone in adolescents with schizophrenia: an open pilot study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 36:694–700Crossref, Google Scholar

Baldessarini RJ, Teicher MH (1995), Dosing of antipsychotic agents in pediatric populations. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 5:1–4Crossref, Google Scholar

Baumeister AA, Seven JA, King BH (1998), Neuroleptics. In: Psychotropic Medications and Developmental Disabilities: The International Consensus Handbook, Reiss S, Aman MG, eds. Baltimore: Paul H. Brookes, pp 133–150Google Scholar

Blackburn GL (2000), Weight gain and antipsychotic medication. J Clin Psychiatry 61(suppl 8):36–42Google Scholar

Brook RH, Chassin MR, Fink A, Solomon DH, Kosecoff J, Park RE (1986), A method for the detailed assessment of the appropriateness of medical technologies. Int J Technol Assess Health Care 2:53–63Crossref, Google Scholar

Campbell M, Armenteros JL, Malone RP, Adams PB, Eisenberg ZA, Overall JE (1997), Neuroleptic-related dyskinesias in autistic children: a prospective, longitudinal study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 36:835–843Crossref, Google Scholar

Campbell M, Gonzalez NM, Silva RR (1992), The pharmacologic treatment of conduct disorders and rage outbursts. Psychiatr Clin North Am 15:69–85Crossref, Google Scholar

Campbell M, Perry R, Green WH (1984), Use of lithium in children and adolescents. Psychosomatics 25:95–106Crossref, Google Scholar

Campbell M, Rapoport JL, Simpson GM (1999), Antipsychotics in children and adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 38:537–545Crossref, Google Scholar

Carnahan RM, Lund BC, Perry PJ (2001), Ziprasidone, a new atypical antipsychotic drug. Pharmacotherapy 21:717–730Crossref, Google Scholar

Citrome L, Volavka J (2000), Management of violence in schizophrenia. Psychiatr Ann 30:41–52Crossref, Google Scholar

Conners CK, March JS, Frances A, Wells KC, Ross R (2001), Treatment recommendations of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: Expert Consensus Guidelines. J Atten Disord 4(suppl):S7–S13Google Scholar

Connor DF, Glatt SJ, Lopez ID, Jackson D, Melloni RH (2002), Psychopharmacology and aggression, I: a meta-analysis of stimulant effects on overt/covert aggression-related behaviors in ADHD. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 41:253–261Crossref, Google Scholar

Crismon ML, Canales PL (2002), Side effect profiles of antipsychotic medications: a basis for drug selection. In: Informed Prescriber, Merck-Medco Managed Care, LLC 2(2):1–4Google Scholar

Crismon ML, Dorson PG (2002), Schizophrenia. In: Pharmacotherapy: A Pathophysiologic Approach, 5th ed, DiPiro JT, Talbert RL, Yee GC, Matzke GR, Wells BG, Posey LM, eds. New York: McGraw-Hill, pp 1219–1242Google Scholar

Daniel DG, Potkin SG, Reeves KR, Swift RH, Harrigan EP (2001), Intramuscular (IM) ziprasidone 20 mg is effective in reducing acute agitation associated with psychosis: a double-blind, randomized trial. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 155:128–134Crossref, Google Scholar

DeBattista C, Schatzberg AF (2001), Current psychotropic dosing and monitoring guidelines: 2001. Prim Psychiatry 8:59–77Google Scholar

Edelbrock CS (1985), Child Behavior Rating Form. Psychopharmacol Bull 21:835–837Google Scholar

Findling RL, McNamara NK, Gracious BL (2000), Paediatric uses of atypical antipsychotics. Expert Opin Pharmacother 1:935–945Crossref, Google Scholar

Fishel AH, Ferreiro DW, Rynerson BC, Nickell M, Jackson B, Hannan BD (1994), As needed psychotropic medications: prevalence, indications, and results. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv 32:27–32Google Scholar

Foxx RM (1998), A comprehensive treatment program for inpatient adolescents. Behav Interventions 13:67–77Crossref, Google Scholar

Geller B, Cooper TB, Sun K et al. (1998), A double-blind and placebo controlled study of lithium for adolescent bipolar disorders with secondary substance dependency. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 37:171–178Crossref, Google Scholar

Gillberg C (2000), Typical neuroleptics in child and adolescent psychiatry. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 9(suppl 1):I/2–I/8Google Scholar

Goff DC, Posever T, Herz L et al. (1998), An exploratory haloperidol-controlled dose-finding study of ziprasidone in hospitalized patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol 18:296–304Crossref, Google Scholar

Greenhill LL, Ford RE (2002), Childhood attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: pharmacological treatments. In: A Guide to Treatments That Work, 2nd ed. Nathan PE, Gorman JM, eds. London: Oxford University Press, pp 25–55Google Scholar

Halperin JM, McKay KE, Newcorn JH (2002), Development, reliability, and validity of the Children’s Aggression Scale–Parent Version. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 41:245–252Crossref, Google Scholar

Hughes CW, Emslie GJ, Crismon ML et al. and the Texas Consensus Conference Panel on Medication Treatment of Childhood Major Depressive Disorder (1999), The Texas Childhood Medication Algorithm Project: report of the Texas Consensus Conference Panel on Medication Treatment of Childhood Major Depressive Disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 38:1442–1454Crossref, Google Scholar

Kafantaris V (1995), Treatment of bipolar disorder in children and adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 34:732–741Crossref, Google Scholar

Kafantaris V, Coletti DJ, Dicker R, Padula G, Pollack S (1998), Are childhood psychiatric histories of bipolar adolescents associated with family history, psychosis, and response to lithium treatment? J Affect Disord 5:153–164Google Scholar

Kahn DA, Docherty JP, Carpenter D, Frances A (1997), Consensus methods in practice guideline development: a review and description of a new method. Psychopharmacol Bull 33:631–639Google Scholar

Kane JM, Marder SR (1993), Psychopharmacologic treatment of schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 19:287–302Crossref, Google Scholar

Kaplan SL, Busner J (1997), Prescribing practices of inpatient child psychiatrists under three auspices of care. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 7:275–286Crossref, Google Scholar

Kapur S, Seeman P (2001), Does fast dissociation from the dopamine D(2) receptor explain the action of atypical antipsychotics? A new hypothesis. Am J Psychiatry 158:360–369Crossref, Google Scholar

Kay SR, Wolkenfeld F, Murrill LM (1988), Profiles of aggression among psychiatric patients. J Nerv Ment Dis 176:539–546Crossref, Google Scholar

Keller MB, Ryan ND, Strober M et al. (2001), Efficacy of paroxetine in the treatment of adolescent major depression: a randomized, controlled trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 40:762–772Crossref, Google Scholar

Klein RG, Abikoff H (1997), Behavior therapy and methylphenidate in the treatment of children with ADHD. J Atten Disord 2:89–114Crossref, Google Scholar

Kolko DJ (1988), Daily ratings on a child psychiatric unit: psychometric evaluation of the Child Behavior Rating Form. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 27:126–132Crossref, Google Scholar

Kowatch RA, Suppes T, Carmody TJ et al. (2000), Effect size of lithium, divalproex sodium, and carbamazepine in children and adolescents with bipolar disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 39:713–720Crossref, Google Scholar

Kronenberger WG, Carter BD, Causey D (2001), Utility of the Pediatric Inpatient Behavior Scale in an inpatient psychiatric setting. J Clin Psychol 57:1421–1434Crossref, Google Scholar

Kronenberger WG, Carter BD, Thomas D (1997), Assessment of behavior problems in pediatric inpatient settings: development of the Pediatric Inpatient Behavior Scale. Child Health Care 26:211–233Crossref, Google Scholar

Kumra S, Brigugio C, Lenane M et al. (1999), Including children and adolescents with schizophrenia in medication-free research. Am J Psychiatry 156:1065–1068Google Scholar

Kumra S, Frazier JA, Jacobsen LK et al. (1996), Childhood-onset schizophrenia: a double-blind clozapine-haloperidol comparison. Arch Gen Psychiatry 53:1090–1097Crossref, Google Scholar

Kumra S, Herion D, Jacobsen LK, Briguglia C, Grothe D (1997), Case study: risperidone-induced hepatotoxicity in pediatric patients. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 36:701–705Crossref, Google Scholar

Lehman AF, Steinwachs, DM, and the Co-Investigators of the PORT Project (1998), At issue: translating research into practice: the Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT) treatment recommendations. Schizophr Bull 24:1–10Crossref, Google Scholar

Leon SC, Lyons JS, Uziel-Miller ND, Tracy P (1999), Psychiatric hospital utilization of children and adolescents in state custody. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 38:305–310Crossref, Google Scholar

Lewis R (1998), Typical and atypical antipsychotics in adolescent schizophrenia: efficacy, tolerability, and differential sensitivity to extrapyramidal symptoms. Can J Psychiatry 43:596–604Google Scholar

Lore C (2000), Risperidone and withdrawal dyskinesia. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 39:941Crossref, Google Scholar

Lyons JS (1998), The Severity and Acuity of Psychiatric Illness: Child and Adolescent Version. San Antonio, TX: Psychological CorporationGoogle Scholar

Malone RP, Sheikh R, Zito JM (1999), Novel antipsychotic medications in the treatment of children and adolescents. Psychiatr Serv 50:171–174Crossref, Google Scholar

Malone RP, Simpson GM (1998), Use of placebos in clinical trials involving children and adolescents. Psychiatr Serv 49:1413–1414, 1417Crossref, Google Scholar

McClellan J, Werry J (1994), Practice parameters for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with schizophrenia. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 33:616–635Crossref, Google Scholar

McEvoy JP, Scheifler PL, Frances A (1999), Treatment of schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry 60(suppl 11):4–80Google Scholar

Measham TJ (1995), The acute management of aggressive behavior in hospitalized children and adolescents. Can J Psychiatry 40:330–336Google Scholar

Meehan K, Zhang F, David S et al. (2001), A double-blind, randomized comparison of the efficacy and safety of intramuscular injections of olanzapine, lorazepam, or placebo in treating acutely agitated patients diagnosed with bipolar mania. J Clin Psychopharmacol 21:389–397Crossref, Google Scholar

Miller AL, Chiles JA, Chiles JK, Crismon ML, Rush AJ, Shon SP (1999), The TMAP schizophrenia algorithms. J Clin Psychiatry 60:649–657Crossref, Google Scholar

MTA Cooperative Group (1999), A 14 month randomized clinical trial of treatment strategies for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: the Multimodal Treatment Study of Children with Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (MTA Study). Arch Gen Psychiatry 56:1073–1086Crossref, Google Scholar

National Institute of Mental Health (1985), Special feature: rating scales and assessment instruments for use in pediatric psychopharmacology research. Psychopharmacol Bull 21:713–1125Google Scholar

New York State Office of Mental Health (1997), Managing Out-of Control Behavior in Children and Adolescents: A Comprehensive Training GuideGoogle Scholar

Overall JE, Pfefferbaum B (1982), The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale for Children. Psychopharmacol Bull 18:10–16Google Scholar

Pappadopulos E, Jensen PS, Schur SB et al. (2002), “Real world” atypical antipsychotic prescribing practices in public child and adolescent inpatient settings. Schizophr Bull 28:111–121Crossref, Google Scholar

Patel NC, Sanchez RJ, Johnsrud MT, Crismon ML (2002), Trends in antipsychotic use in a Texas Medicaid population of children and adolescents: 1996 to 2000. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 12:219–227Crossref, Google Scholar

Patel VL, Ramoni MF (1997), Cognitive models of directional inference in expert medical reasoning. In: Expertise in Context: Human and Machine, Feltovich PJ, Ford KM, eds. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, pp 67–99Google Scholar

Perrin S, Smith P, Yule W (2000), The assessment and treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder in children and adolescents. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 41:277–289Crossref, Google Scholar

Perry R, Pataki C, Munoz-Silva DM, Armenteros J, Silva RR (1997), Risperidone in children and adolescents with pervasive developmental disorder: pilot trial and follow-up. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 7:167–179Crossref, Google Scholar

Pine DS, Walkup JT, Labellarte MJ et al. (2001), Fluvoxamine for the treatment of anxiety disorders in children and adolescents. N Engl J Med 344:1279–1285Crossref, Google Scholar

Pliszka SR, Greenhill LL, Crismon ML et al. and the Texas Consensus Conference Panel on Medication Treatment of Childhood Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (2000a), The Texas Children’s Medication Algorithm Project: report of the Texas Consensus Conference Panel on Medication Treatment of Childhood Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder, part I. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 39:908–919Crossref, Google Scholar

Pliszka SR, Greenhill LL, Crismon ML et al. and the Texas Consensus Conference Panel on Medication Treatment of Childhood Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (2000b), The Texas Children’s Medication Algorithm Project: report of the Texas Consensus Conference Panel on Medication Treatment of Childhood Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder, part II: tactics. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 39:920–927Crossref, Google Scholar

Ray WA, Meredith S, Thapa PB, Meador KG, Hall K, Murray KT (2001), Antipsychotics and the risk of sudden cardiac death. Arch Gen Psychiatry 58:1161–1167Crossref, Google Scholar

Reilly JG, Ayis SA, Ferrier IN, Jones SJ, Thomas SH (2000), QTc-interval abnormalities and psychotropic drug therapy in psychiatric patients. Lancet 355:1048–1052Crossref, Google Scholar

Remschmidt H, Hennighausen K, Clement HW, Heiser P, Schulz E (2000), Atypical neuroleptics in child and adolescent psychiatry. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 9(suppl 1):I/1–I/19Google Scholar

Renaud J, Birmaher B, Wassick SC, Bridge J (1999), Use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for the treatment of childhood panic disorder: a pilot study. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 9:73–83Crossref, Google Scholar

Richardson MA, Haugland G, Craig TJ (1991), Neuroleptic use, parkinsonian symptoms, tardive dyskinesia, and associated factors in child and adolescent psychiatric patients. Am J Psychiatry 148:1322–1328Crossref, Google Scholar

Riddle MA, Reeve EA, Yaryura-Tobias JA et al. (2001), Fluvoxamine for children and adolescents with obsessive-compulsive disorder: a randomized, controlled, multicenter trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 40:222–229Crossref, Google Scholar

Robinson D, Woerner, MG, Alvir JM et al. (1999), Predictors of relapse following response from a first episode of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 56:241–247Crossref, Google Scholar

Rosenheck RA (2001), Organizational process: a missing link between research and practice. Psychiatr Serv 52:1607–1612Crossref, Google Scholar

Rowan AB, Malone RP (1997), Tics with risperidone withdrawal. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 36:162–163Crossref, Google Scholar

Rush AJ (2001), Practice guidelines and algorithms. In: Treatment of Depression: Bridging the 21st Century, Weissman MM, ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, pp 213–240Google Scholar

Rush AJ, Frances A, eds (2000), Expert Consensus Guideline Series: treatment of psychiatric and behavioral problems in mental retardation. Am J Ment Retard 105:159–238Google Scholar

Ryan ND, Bhatara VS, Perel JM (1999), Mood stabilizers in children and adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 38:529–536Crossref, Google Scholar

Sallee FR, Kurlan R, Goetz CG et al. (2000), Ziprasidone treatment of children and adolescents with Tourette’s syndrome: a pilot study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 39:292–299Crossref, Google Scholar