Gender, Estrogen, and Schizophrenia

Abstract

Most of the evidence to support an association between estrogen and psychosis is indirect and comes from clinical studies of gender differences in schizophrenia and from studies of fluctuating levels of psychopathology in different phases of the menstrual cycle. Our data, as well as those of other investigators, suggest a significantly later age at onset of schizophrenia in women than in men. There is somewhat more direct evidence from animal studies indicating that estrogen modulates dopamine systems in a manner similar to neuroleptics, although there are some inconsistencies in the literature. Few studies have examined the effects of estrogen administration in conjunction with neuroleptics on psychotic symptoms. We present a case report of a postmenopausal woman with schizophrenia who had an improvement in positive symptoms with estrogen replacement therapy. Long-term double-blind treatment studies are needed to investigate the effects of estrogen on psychotic symptoms in women with schizophrenia.

Although gender differences in schizophrenia have been noticed since the time of Kraepelin (1909), these have not been systematically studied until recently. A literature review examining gender differences in schizophrenia (Wahl and Hunter 1992) found that 72 percent of the studies appearing in four major journals from 1985 to 1989 included more male than female subjects. The heterogeneity in the clinical presentation of schizophrenia, however, has recently led a number of investigators to examine how the role of gender may be involved in the development of the disorder and/or the modification of its expression. There is some indirect evidence that some gender differences in schizophrenia may be related to levels of reproductive hormones. In this article, evidence from clinical studies suggesting a relationship between estrogen and clinical features of schizophrenia is discussed, followed by evidence from preclinical studies investigating the relationship between estrogen and dopamine. Treatment studies are reviewed and a case report is presented.

Clinical studies

Gender differences in age of onset

Later age of onset of schizophrenia in women has been observed regardless of the definition of onset, source of information, sample, or method of sampling (Maurer and Hafner 1995). On average, women are diagnosed with schizophrenia 2 to 10 years later than men (Harris and Jeste 1988; Riecher et al. 1990). In addition to a delayed peak of onset of schizophrenia for women, some, but not all, investigators have found an additional smaller peak after ages 40 to 45, around the time of decreasing levels of estrogen (Hafner et al. 1992, 1993). The timing and gender specificity of this increased prevalence of schizophrenia have led some researchers to speculate that estrogen levels protect women from developing schizophrenia and that the drop in estrogen levels associated with menopause may put women at risk to develop schizophrenia later in life (Riecher-Rossler and Hafner 1993; Seeman and Lang 1990).

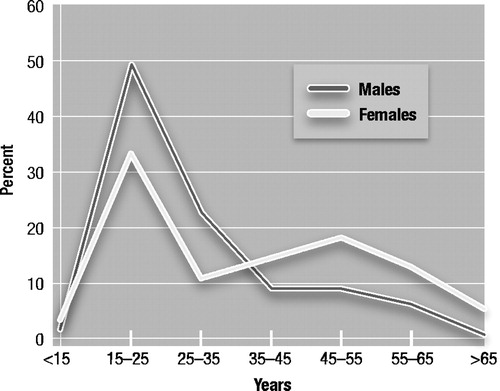

We examined gender differences in age of onset of schizophrenia in 194 outpatients between the ages of 35 and 97 years. The majority of patients were recruited from the Veterans Affairs Medical Center, San Diego, CA, and many women were recruited from the University of California, San Diego Outpatient Psychiatric Clinics. Details of recruitment are reported elsewhere (Jeste et al. 1995). Although this was not an epidemiological study, the results were consistent with the literature. Figure 1 shows the percentages of men and women whose age of onset fell within the labeled decade. Below the age of 25, more men (51.4%) than women (37.0%) developed schizophrenia. After the age of 45, however, the percentage of schizophrenia in women (37.0%) was higher than in men (16.4%). Results of a non-parametric test of independent samples (Kolmogorov-Smirnov test) revealed that the distributions were significantly different (K-S z-score=1.63, p<.01). The mean age of onset for men was 30.10 (±13) years and for women was 38.7 (±17.9) years. Furthermore, significantly more women (37.0%) than men (16.4%) had an age of onset of schizophrenia after the age of 45, meeting the DSM-III-R (American Psychiatric Association, 1987) criterion for late-onset schizophrenia (chi-square=9.6, p<.01).

Other gender differences in older patients with schizophrenia

Additional gender differences were observed in a sample of older patients with schizophrenia from our Clinical Research Center (Lindamer et al. 1999). The sample consisted of 36 women and 86 men with schizophrenia who did not differ significantly in terms of age, overall cognitive functioning, or general psychopathology. Although more women than men were diagnosed with paranoid subtype, this difference was not statistically significant. In terms of clinical presentation, older women with schizophrenia had a significantly higher total score on the Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SAPS; Andreasen 1984), and lower scores on the Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS; Andreasen 1981) compared with men. Even when considering the gender differences in age of onset, women still had significantly more severe positive symptoms.

Our results of gender differences in older patients with schizophrenia are consistent with studies demonstrating that women have later age of onset, more severe positive symptoms, and less severe negative symptoms (Andia and Zisook 1991; Andia et al. 1995). Our data (Harris et al. 1997) are also consistent with a study reporting no differential relationship of schizophrenia to cognitive performance for the two genders (Goldberg et al. 1995), but inconsistent with data from a study reporting that women with schizophrenia were more neuropsychologically impaired than their male counterparts (Lewine et al. 1996). We have examined structural brain abnormalities in a small sample of older patients and found no consistent gender differences in MRI abnormalities over and above what is seen in normal comparison subjects.

What do these gender differences tell us about estrogen and schizophrenia? There are two viewpoints presented in the literature (Lindamer and Jeste 1999). One position is that there are different subtypes of schizophrenia for men and women. One subtype with earlier onset and consequently poorer premorbid functioning is over-represented in men (Lewine 1981). Further evidence for this viewpoint comes from the results of latent class analysis of gender differences in schizophrenia (Castle et al. 1994; Goldstein et al. 1990). The other position is that the same type of schizophrenia afflicts both men and women but that the onset of schizophrenia shifts to a later age in women. To account for such “protection” from schizophrenia in young adulthood, researchers have proposed that premenopausal estrogen levels may increase the threshold of susceptibility for schizophrenia; after menopause when estrogen levels have dropped significantly, the risk for developing schizophrenia increases for women.

Relationship between estrogen levels and psychopathology

Further evidence for an association between estrogen and psychosis comes from the literature investigating psychopathology over different phases of the menstrual cycle in premenopausal women with schizophrenia. Hallonquist and colleagues (1993) studied severity and types of psychopathology in 5 outpatient women (ages 29 to 49) with schizophrenia over two consecutive menstrual cycles. All the women had regular menstrual cycles, were receiving neuroleptic medication, and were not taking oral contraceptives. The authors assessed the severity of depression, psychotic symptoms, somatization, phobia, anxiety, and hostility, as well as global psychopathology using the Abbreviated Symptom Checklist (McNiel et al. 1989). Only global psychopathology scores were significantly lower during the high estrogen phase of the menstrual cycle and higher during the low estrogen phase. There were no significant differences on any specific measures of psychopathology. While these results are intriguing, there are several methodological concerns that make drawing conclusions about the relationship of estrogen and psychopathology premature. For example, no blood levels of estradiol were assayed and the sample size was very small. Additionally, the only significant difference was in overall psychopathology which raises questions about the sensitivity of the Abbreviated Symptom Checklist and/or the specificity of the effect of estradiol.

In another study of fluctuations in psychopathology over the menstrual cycle, Riecher-Rossler and coworkers (1994a, 1994b) measured levels of estradiol and found that when the levels were high, less psychopathology was seen. In the first study, the authors assessed psychopathology in 32 acutely hospitalized women with schizophrenia on several days within a single menstrual cycle using the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS; Overall and Gorham 1962), a nurses’ observation scale (NOSIE; Honigfeld et al. 1976), and a self-rating scale of paranoid and depressive symptoms and well-being (v. Zerssen and Koeller 1976). Serum levels of several hormones, including estradiol, were assayed. Symptoms improved when estradiol levels were high and this relationship was significant for the total score on the BPRS, nurses’ behavioral ratings, and self-rated levels of paranoia and well-being but not of depression. Further analysis of the BPRS subscales revealed a significant inverse relationship between estradiol and the thought disturbance subscale, which the authors concluded supported the inverse relationship of estradiol to specific psychopathology in schizophrenia. This reduction in positive symptoms with increasing estradiol levels would also be consistent with the view that estrogen has neuroleptic-like effects, as positive symptoms of schizophrenia are believed to be linked with increased dopaminergic activity (Davis et al. 1991). In a companion study (Riecher-Rossler et al. 1994b), the relationship between estradiol levels and measures of psychopathology was examined in a sample of affective disorder patients. There was no significant relationship between the BPRS or Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (Hamilton 1967) and estradiol levels for the affective disorder group. The authors suggested that the association between estradiol and psychopathology could be somewhat specific to schizophrenia; however, there have been other reports that estrogen improves depressive symptoms in women with and without a psychiatric diagnosis (Broverman et al. 1981; Sherwin and Gelfand 1985).

A study of hospitalized patients reported that when estrogen levels were rising, women with schizophrenia required lower doses of neuroleptics (Gattaz et al. 1994). The therapeutic response, as measured by duration of hospitalization, amount of neuroleptics, and clinical status at discharge, was measured in 65 women with a diagnosis of schizophrenia and 35 women with a diagnosis of affective disorder. The women with schizophrenia required lower doses of neuroleptic medication if they were admitted during phases of menstrual cycle when estrogen levels were low. These women also had shorter hospital stays, but this difference was not statistically different. There was no difference in clinical status at discharge between women with schizophrenia admitted during the high versus low estrogen phases of the menstrual cycle. The authors concluded that the rising levels of estrogen during the hospitalization were responsible for the improvement in therapeutic response.

There is also some evidence the higher levels of estrogen during pregnancy may protect women from psychosis. Women with a diagnosis of schizophrenia have been noted to have an improvement in their symptoms during pregnancy and to have vulnerability to psychosis postpartum. There are reports of an increase in psychiatric hospitalizations for psychosis postpartum relative to antepartum (Kendell et al. 1987). Furthermore, postmenopausal women may also demonstrate increased vulnerability to psychosis compared to premenopausal women (Seeman 1983). Kendell and colleagues (1987) reported that hospital admissions were 21.7 times more likely in the first month and 12.7 times within 3 months postpartum relative to antepartum for psychosis related to depression or schizophrenia. Furthermore, an increase in dopamine sensitivity postpartum was seen in women at risk for bipolar or schizoaffective disorder (Wieck et al. 1991). There is some evidence that the relationship between estrogen levels and psychosis may be somewhat specific to diagnosis. McNeil (1987) found that following delivery, mothers with schizophrenia had a relapse rate of psychosis of 23.5 percent, whereas 46.7 percent of the mothers with affective or cycloid psychosis relapsed. Davies and colleagues (1995) investigated hospitalizations for psychosis following childbirth using two different criteria for the diagnosis of schizophrenia: one group had a strict definition of schizophrenia, the other group included affective symptoms in the definition. Forty-three percent of the broadly defined subjects were admitted with “an acute illness episode” versus none of the mothers in the narrowly defined schizophrenic mothers. Since both groups were symptomatic during pregnancy, the authors argued that increased levels of estrogen could not have been protective against psychosis regardless of diagnosis. The type and severity of symptoms during the pregnancy, however, were not reported. The authors concluded that the lower relapse rate postpartum in the narrowly defined group suggested that low estrogen states do not represent high risk time for all schizophrenic women. Alternatively, women diagnosed with the broad criterion may have been admitted for symptoms other than psychosis or may have been more accurately diagnosed as having affective psychosis. In contrast, Da Silva and Johnstone (1981) investigated the social functioning of 38 mothers with psychiatric disorders and their babies. These investigators reported that only 1 of the 17 women with the diagnosis of schizophrenia had good social functioning (no symptoms or social impairment) compared with 15 of 21 women with affective disorder.

Data from some clinical studies of gender differences, although not all, provide indirect evidence that estrogen may confer a protective effect against developing schizophrenia, delaying its onset until menopause. Correlational studies of the menstrual cycle and estrogen levels suggest that estradiol may act like a neuroleptic to reduce psychopathology associated with schizophrenia, especially the positive symptoms. This evidence suggests that estrogens may be interacting in some way with the dopamine systems thought to be involved in schizophrenia. More direct evidence demonstrating the effects of estrogens on dopamine systems comes from animal studies, both behavioral and biochemical.

Preclinical studies

Behavioral studies of the relationship between estrogen and dopamine

Preclinical animal studies provide some direct evidence for the modulation of dopamine systems by estrogen. In some behavioral studies, estrogen produced a decrease in dopamine-related behaviors, such as locomotor and rotational behaviors (Bedard et al. 1981; Euvrard et al. 1979). Estrogen has also been shown to reduce amphetamine- and apomorphine-induced stereotypies (Gordon and Diamond 1981; Hafner et al. 1991; Hruska and Silbergeld 1980), as well as to enhance neuroleptic-induced catalepsy (Chiodo et al. 1979; Di Paolo et al. 1981; Gordon et al. 1980; Hafner et al. 1991).

In these behavioral studies, estrogen seems to act in a manner similar to blocking dopamine receptors. This neuroleptic-like effect seen in animal studies is consistent with the notion that estrogen is protective and that decreasing levels may increase vulnerability to manifesting schizophrenia.

While there is much evidence to support a neuroleptic-like (anti-dopaminergic) effect of estrogen, there is also some evidence that estrogen enhances dopamine-related behaviors. Nausieda and colleagues (1979) found that oophorectomy decreased apomorphine- or amphetamine-induced stereotyped behaviors in guinea pigs and that estradiol replacement restored the stereotyped behaviors.

Other studies have demonstrated a biphasic effect of estrogen. Bedard and colleagues (1984) lesioned regions in midbrain of monkeys which resulted in tongue protrusion and rolling, as well as lateral jaw movements, that were enhanced by dopamine agonists and decreased by dopamine antagonists. Using this monkey model of lingual dyskinesia, the authors investigated the effects of estradiol and haloperidol on dopamine and motor behaviors. The investigators measured levels of apomorphine-induced tongue protrusion in ovariectomized monkeys and then administered either estradiol or haloperidol. Both estradiol and haloperidol produced a 75 percent decrease in apomorphine-induced dyskinesia 24 hours after administration and an increase in dyskinesia 2 weeks later. The specificity of the estrogen effect was demonstrated in another experiment using the midbrain lesion (Bedard et al. 1983). Following the lesion and ovariectomy, some monkeys developed a tremor that was suppressed by the administration of apomorphine. Chronic estradiol treatment had no effect on the tremor. In contrast, the lingual dyskinesia which increased with apomorphine administration was reduced by either a single dose or chronic administration of estradiol.

Biochemical studies of the relationship between estrogen and dopamine

Preclinical biochemical studies also indicate that estrogen has a modulatory effect on dopamine systems, however, the results are somewhat contradictory. Estrogen appears to up-regulate or down-regulate dopamine systems depending on the time course of its administration (Van Hartesveldt and Joyce 1986). Acute in vivo administration of estradiol decreased the affinity of [3H] spiroperidol for the D2 receptor in the rat striatum (Gordon and Perry 1983; Hafner et al.1991); it also decreased the ratio of high-affinity to low-affinity dopamine agonist sites (Clopton and Gordon 1985). Chronic administration of estradiol to ovariectomized rats also decreased the content of dopamine in several brain nuclei, but did not alter dopamine turnover (Dupont et al. 1981).

In contrast, some studies found that estrogen treatment of ovariectomized rats resulted in an increase in the number of dopamine receptors (Di Paolo et al. 1979, 1982). This result was replicated by Hruska and Silbergeld (1980) with a single high dose 17B estradiol (125 ug) in male rats. The number of dopamine receptors labeled with [3H] spiroperidol increased by about 20 percent, and there was no change in binding affinity. Both estradiol and haloperidol increased the number of striatal dopamine receptors in ovariectomized female rats, and the effect was additive when both treatments were administered (Dupont et al. 1981). Bedard and colleagues (1984) raised a question whether an increase in receptors could indicate facilitation or be a consequence of receptor blockade following haloperidol administration, since haloperidol initially blocks receptors and then produces supersensitivity. Therefore, the authors cautioned that the dose and time of observation after the last dose must be considered.

What can be made of these inconsistent results? Perhaps acute administration in animals more closely mimics the fluctuations in estrogen levels seen in women. Chronic, high doses of estrogen may not be relevant as women are typically not exposed to sustained high levels of estrogen.

To summarize the preclinical studies, acutely administered estrogen may act similar to neuroleptics on dopamine-associated behaviors and biochemical studies have shown that estrogen can alter dopamine receptor density and affinity, although the effect is dependent on the time course of the administration.

Treatment studies

There have been few treatment studies investigating the effect of estrogen on psychopathology in women with schizophrenia. Kulkarni and colleagues (1995) reported that the administration of 0.02 mg estradiol to premenopausal women with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder for 1 month in conjunction with standardized neuroleptic treatment decreased the total score on the SAPS to a greater extent than in a comparison group of women who received neuroleptics only. At the end of 2 months’ treatment with estradiol, however, the scores on the SAPS increased. Kulkarni and colleagues concluded that estradiol might enhance the effects of neuroleptics to reduce positive symptoms initially but that this effect might be reversed with longer administration of estradiol. There has also been a case report of the effect of estrogen treatment on psychotic symptoms in a 48-year-old woman with schizoaffective disorder with premenstrual exacerbation of symptoms. Treatment with 3.0 mg of estradiol (percutaneous) for 5 months increased her serum level of estradiol from 50 pmol/L to 140 pmol/L and increased her subjective sense of well-being (Korhonen et al. 1995). The patient self-discontinued her “psychotropic” medication (the type of medication was unspecified) 1 month after beginning estrogen therapy and had no relapse over the next year.

Recently, we designed a treatment study to investigate the effects of estrogen supplementation in postmenopausal women with schizophrenia. Outpatient women stable on neuroleptics receive psychiatric and neurological examinations. After a comprehensive physical evaluation, including a mammogram, pelvic examination, Pap smear, and vaginal ultrasound, subjects are considered for possible eligibility for the study. We administer transdermal patches of 0.05 to 0.10 mg of Estraderm, changing twice a week for 4 months. Standardized measures of psychopathology and motor function are given monthly, and blood is drawn for measuring levels of estradiol and neuroleptics. Cognitive functioning (i.e., attention, learning, and memory) is evaluated at baseline, 2 months, and 4 months. Below we present a selected case report of estradiol augmentation of neuroleptics, in a postmenopausal woman with schizophrenia.

Case report

Ms. A was a 49-year-old, divorced, Caucasian woman who completed high school and earned an Associates Degree in Human Growth and Development at a community college. She then worked as a teacher in a nursery school and later in a school for developmentally delayed children. In 1971, she enlisted in the Navy, working as a secretary and dental technician. She married and was honorably discharged in 1972 due to pregnancy. She divorced in 1979 and moved in with her parents, giving her 4 children up for adoption. Although she attended adult education classes to become a medical assistant, worked as a security guard, and obtained a cosmetology license, she had difficulty maintaining employment and went into debt. Her living arrangements alternated between living with partners when she was involved in a relationship and living with her parents when the relationship ended.

Her psychiatric history consisted of evaluation at the age of 12 for an unspecified learning disability. The age at first psychiatric contact for possible schizophrenia was 26 years when Ms. A was seen for several weeks for “apprehension” while in the service. Although she continued to experience disorganization in her thoughts and behavior, she was not diagnosed as having schizophrenia nor did she receive regular psychiatric care until 1995.

In April, 1995, Ms. A’s mother died. Ms. A was referred by a gastroenterologist three months later to the Psychiatric Emergency Clinic, stating that she could not earn a living because of depression, confusion, and poor memory and concentration. After several outpatient appointments, she was hospitalized for the first time in August 1995 with tangential speech, disorganized behavior, mild paranoia, and inappropriate affect. Ms. A described her condition as feeling like “there is something wrong with my brain.” She denied auditory and visual hallucinations at admission but manifested auditory hallucinations during her hospital course; these resolved before discharge. A structured clinical interview (SCID; Spitzer et al. 1988) revealed that in the past, Ms. A had experienced hearing voices commenting on her behavior, as well as visual, tactile, and olfactory hallucinations. On observation, she demonstrated loosening of associations, incoherence, inappropriate affect, and posturing. Although she described some depressed mood, she denied anhedonia and other symptoms of depression. DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association 1994) symptoms of mania were not observed. Ms. A denied a history of alcohol or other drug abuse, seizure disorder, closed head injury, or other neurological disorder. Family psychiatric history was positive for schizophrenia in her aunt and mother. Her DSM-IV diagnosis was schizophrenia, disorganized type (295.10).

Medical history was significant for spastic colitis, asthma, and vitamin B12 deficiency. She had a bladder suspension in 1977 and a hysterectomy in 1979 for menorrhagia related to leiomyoma. Physical examination was unremarkable. CT head scan was within normal limits.

On neuropsychological performance, Ms. A scored a 29/30 on the Mini-Mental State Examination (Folstein et al. 1975). Her WAIS-R Full Scale Intelligence Quotient (I.Q.) (Wechsler 1981) was 100, her verbal I.Q. was 106, and her performance I.Q. was 93, thus placing her intellectual functioning in the average range. Her performance on the WAIS-R subtests was in the low average to average range with the exception of a test of attention to visual detail (Picture Completion) which fell in the mildly to moderately impaired range. Ms. A demonstrated a mild impairment of visuospatial learning (Story Learning) and concept formation (Booklet Category Test). Achievement tests of reading comprehension and spelling (PLAT) were in the mildly to severely impaired range, respectively, confirming her subjective complaints of learning difficulties. Reading recognition, however, was in the high average range, greater than a 12 grade level.

Ms. A had never been prescribed neuroleptic medication prior to this hospitalization. At admission, Ms. A’s total score on the positive syndrome scale of the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS; Kay et al. 1987) was 22. Her total score on the negative syndrome scale was 21 and she scored 48 on the global psychopathology scale. During her hospital course, Ms. A was enrolled in a randomized, double-blind drug study of an atypical antipsychotic. She discontinued just prior to entering the open-label phase. After terminating the drug study, Ms. A was prescribed perphenazine 8 mg and discharged 3 days later. After about 2 weeks, the dose of perphenazine was increased to 12 mg and remained at that dose for several months. Prior to enrollment into the estrogen replacement therapy (ERT) protocol, Ms. A’s positive, negative, and global psychopathology scores on the PANSS were 15, 7, and 30, respectively. Following 4 months of administration of 0.05 mg Estraderm, her PANSS positive syndrome scale dropped to 9, while her negative syndrome score was 9, and global score 31. After 2 weeks off estradiol, Ms. A requested an increase in her dose of perphenazine “to improve my thinking and to calm me down.” Six weeks after discontinuing the ERT and increasing her dose of perphenazine to 16 mg, Ms. A’s score on the PANSS positive syndrome scale was 22, on the negative syndrome scale was 8, and on the global psychopathology scale was 32. At her request, and as agreed by her physician, she was started on 0.625 mg Premarin and was being monitored for changes in psychopathology.

This case report illustrates the possible beneficial effects of estrogen augmentation of neuroleptic treatment in postmenopausal women with schizophrenia. In this case, a middle-aged woman with schizophrenia had a reduction in positive symptoms (but not in negative symptoms or global psychopathology) while on ERT and a return of near baseline levels of positive symptoms when ERT was discontinued. While this single-case open study of the effects of ERT on psychopathology is intriguing, larger, double-blind treatment studies are needed.

In conclusion, the indirect evidence from clinical studies of gender differences in schizophrenia and from studies examining the relationship between levels of estrogens and psychopathology suggests a potential role for estrogen in delaying the onset or attenuating the severity of psychotic symptoms associated with schizophrenia. Direct evidence from biochemical and behavioral studies in animals indicates that estrogen interacts with dopamine, suggesting one possible mechanism for the protective effect of estrogen in schizophrenia. This hypothesis is partially supported from data from one published small open-label treatment study and the case study presented here of the estrogen augmentation of neuroleptic medication in postmenopausal women with schizophrenia. Adjunctive treatment of estrogen has considerable potential clinical significance, such as allowing a decrease in the dose of neuroleptic medication while maintaining efficacy and reducing the associated side effects. More studies, especially double-blind, randomized clinical trials of the effects of estrogen replacement therapy in conjunction with neuroleptic treatment on the psychopathology in schizophrenia are required before definitive conclusions about the benefits of estrogen supplementation can be drawn.

Figure 1. Distributions of Percentages of Males and Females Falling Within Decades of Age of Onset of Schizophrenia

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 3rd ed., revised. Washington, DC: The Association, 1987.Google Scholar

American Psychiatric Association. DSM-IV: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed. Washington, DC: The Association, 1994.Google Scholar

Andia, AM; Zisook, S; Heaton, RK; Hesselink, J; Jernigan, T; Kuck, J; Moranville, J; and Braff, DL. Gender differences in schizophrenia. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 183:(8)522–528, 1995.Crossref, Google Scholar

Andia, AM, and Zisook, S. Gender differences in schizophrenia: A literature review. Ann. Clin. Psychiatry 3:333–340, 1991.Crossref, Google Scholar

Andreasen, NC. The Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS). Iowa City: The University of Iowa, 1981.Google Scholar

Andreasen, NC. The Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SAPS). Iowa City: The University of Iowa, 1984.Google Scholar

Bedard, P; Boucher, R; Di Paolo, T; and Labrie, F. Biphasic effect of estradiol and domperidone on lingual dyskinesia in monkeys. Exp. Neurol. 82:(1)172–182, 1983.Crossref, Google Scholar

Bedard, PJ; Di Paolo, T; Langelier, P; Poyet, P; and Labrie, F. Behavioural and biochemical evidence of an effect of estradiol on striatal dopamine receptors. In: Fuxe, K; Gustafsson, JA; and Wetterberg, L, eds. Steroid Hormone Regulation of the Brain. Oxford: Pergamon Press, 1981. pp. 331–339.Google Scholar

Bedard, PJ; Boucher, R; Daigle, M; and Di Paolo, T. Similar effect of estradiol and haloperidol on experimental tardive dyskinesia in monkeys. Psychoneuroendocrinology 9:(4)375–379, 1984.Crossref, Google Scholar

Broverman, DM; Vogel, W; Klaiber, EL; Majcher, D; Shea, D; and Paul, V. Changes in cognitive task performance across the menstrual cycle. J. Comp. Physiol. Psychol. 95:646–654, 1981.Crossref, Google Scholar

Castle, DJ; Sham, PC; Wessely, S; and Murray, RM. The subtyping of schizophrenia in men and women: A latent class analysis. Psychol. Med. 24:41–51, 1994.Crossref, Google Scholar

Chiodo, LA; Caggiula, AR; and Sailer, CF. Estrogen increases both spiperone-induced catalepsy and brain levels of [3H]spiperone in the rat. Brain Res. 172:360–366, 1979.Crossref, Google Scholar

Clopton, JK, and Gordon, JH. The possible role of 2-hydroxyestradiol in the development of estrogen-induced striatal dopamine receptor hypersensitivity. Brain Res. 333:1–10, 1985.Crossref, Google Scholar

Da Silva, L, and Johnstone, EC. A follow-up study of severe puerperal psychiatric illness. Br. J. Psychiatry 139:346–354, 1981.Crossref, Google Scholar

Davies, A; McIvor, RJ; and Kumar, C. Impact of childbirth on a series of schizophrenic mothers: A comment on the possible influence of oestrogen on schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res. 16:25–31, 1995.Crossref, Google Scholar

Davis, KL; Kahn, RS; Ko, G; and Davidson, M. Dopamine in schizophrenia: A review and reconceptualization. Am. J. Psychiatry 148:1474–1486, 1991.Crossref, Google Scholar

Di Paolo, T; Carmichael, R; Labric, F; and Raynaud, JR Effects of estrogens on the characteristics of [3H] spiroperidol and [3H] RU24213 binding in rat anterior pituitary gland and brain. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 16:99–112, 1979.Crossref, Google Scholar

Di Paolo, T; Poyet, P; and Labrie, F. Effect of chronic estradiol and haloperidol treatment on striatal dopamine receptors. Eur J. Pharmacol. 73:105–106, 1981.Crossref, Google Scholar

Di Paolo, T; Poyet, P; and Labrie, F. Prolactin and estradiol increase striatal dopamine receptor density in intact, castrated and hypophysectomized rats. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 6:377–382, 1982.Google Scholar

Dupont, A; Di Paolo, T; Gagne, B; and Barden, N. Effects of chronic estrogen treatment on dopamine concentrations and turnover in discrete brain nuclei of ovariectomized rats. Neurosci. Lett. 22:69–74, 1981.Crossref, Google Scholar

Euvrard, C; Oberlander, C; and Boissier, JR. Antidopaminergic effect of estrogens at the striatal level. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 214:(1)179–185, 1979.Google Scholar

Folstein, MF; Folstein, SE; and McHugh, PR. Mini-Mental State: A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J. Psychiatr Res. 12:189–198, 1975.Crossref, Google Scholar

Gattaz, WF; Vogel, P; Riecher-Rossler, A; and Soddu, G. Influence of the menstrual cycle phase on the therapeutic response in schizophrenia. Biol. Psychiatry 36:137–139, 1994.Crossref, Google Scholar

Goldberg, TE; Gold, JM; Torrey, EF; and Weinberger, DR. Lack of sex differences in the neuropsychological performance of patients with schizophrenia. Am. J. Psychiatry 152:(6)883–888, 1995.Crossref, Google Scholar

Goldstein, JM; Santangelo, SL; Simpson, JC; and Tsuang, MT. The role of gender in identifying subtypes of schizophrenia: A latent class analytic approach. Schizophr. Bull. 16:(2)263–275, 1990.Crossref, Google Scholar

Gordon, JH; Borison, RL; and Diamond, BI. Modulation of dopamine receptor sensitivity by estrogen. Biol. Psychiatry 15:(3)389–396, 1980.Google Scholar

Gordon, JH, and Diamond, BI. Antagonism of dopamine supersensitivity by estrogen: Neurochemical studies in an animal model of tardive dyskinesia. Biol. Psychiatry 16:(4)365–371, 1981.Google Scholar

Gordon, JH, and Perry, KO. Pre- and postsynaptic neurochemical alterations following estrogen-induced striatal dopamine hypo- and hypersensitivity. Brain Res. Bull. 10:425–428, 1983.Crossref, Google Scholar

Hafner, H; Behrens, S; De Vry, J; and Gattaz, WE An animal model for the effects of estradiol on dopamine-mediated behavior: Implications for sex differences in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 38:125–134, 1991.Crossref, Google Scholar

Hafner, H; Riecher-Rossler, A; Maurer, K; Fatkenheuer, B; and Loffler, W. First onset and early symptomatology of schizophrenia: A chapter of epidemiological and neurobiological research into age and sex differences. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Neurol. Sci. 242:109–118, 1992.Crossref, Google Scholar

Hafner, H; Maurer, K; Loffler, W; and Riecher-Rossler, A. The influence of age and sex on the onset and early course of schizophrenia. Br. J. Psychiatry 162:80–86, 1993.Crossref, Google Scholar

Hallonquist, JD; Seeman, MV; Lang, M; and Rector, NA. Variation in symptom severity over the menstrual cycle of schizophrenics. Biol. Psychiatry 33:207–209, 1993.Crossref, Google Scholar

Hamilton, M. Development of a rating scale for primary depressive illness. Br J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 6:278–296, 1967.Crossref, Google Scholar

Harris, MJ; Heaton, SC; Lindamer, LA; Paulsen, JS; Bailey, A; Gladsjo, JA; McAdams, LA; Fell, RL; Zisook, S; Heaton, RK; and Jeste, DV. Gender and schizophrenia. In: Light, E, and Lebowitz, B, eds. Sex Hormones, Aging and Mental Disorders. Washington, DC: National Institute of Mental Health, submitted 1997.Google Scholar

Harris, MJ, and Jeste, DV. Late-onset schizophrenia: An overview. Schizophr. Bull. 14:39–55, 1988.Crossref, Google Scholar

Honigfeld, G; Gillis, RD; and Klett, CJ. NOISE: Nurses observation scale for inpatient evaluation. In: Guy, W, ed. ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology, revised. DHEW Pub. No. (ADM)76-338. Rockville, MD: National Institute of Mental Health, 1976.Google Scholar

Hruska, RE, and Silbergeld, EK. Increased dopamine receptor sensitivity after estrogen treatment using the rat rotation model. Science 208:1466–1468, 1980.Crossref, Google Scholar

Jeste, DV; Neckers, LM; Wagner, RL; Wise, CD; Staub, RA; Rogol, A; Potkin, SG; Bridge, TP; and Wyatt, RJ. Lymphocyte monoamine oxidase and plasma prolactin and growth hormone in tardive dyskinesia. J. Clin. Psychiatry 42:75–77, 1981.Google Scholar

Jeste, DV, Harris, MJ; Krull, A; Kuck, J; McAdams, LA; and Heaton, R. Clinical and neuropsychological characteristics of patients with late-onset schizophrenia. Am. J. Psychiatry 152:(5)722–730, 1995.Crossref, Google Scholar

Kay, SR; Fiszbein, A; and Opler, LA. The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull. 13:2:261–276, 1987.Crossref, Google Scholar

Kendell, RE; Chalmers, JC; and Platz, C. Epidemiology of puerperal psychoses. Br. J. Psychiatry 150:662–673, 1987.Crossref, Google Scholar

Korhonen, S; Saarijarvi, S; and Aito, M. Successful estradiol treatment of psychotic symptoms in the premenstrual phase: A case report. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 92:237–238, 1995.Crossref, Google Scholar

Kraepelin, E. Psychiatrie ein Lehrbuch fur Studierende und Aertzte. Barth, Leipzig, 1909.Google Scholar

Kulkarni, J; de Castella, A; and Smith, D. Adjunctive estrogen treatment in women with schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res. 15:157, 1995.Crossref, Google Scholar

Lewine, R. Sex differences in schizophrenia: Timing or subtype? Psychol. Bull. 90:432–444, 1981.Crossref, Google Scholar

Lewine, RRJ; Walker, EF; Shurett, R; Caudle, J; and Haden, C. Sex differences in neuropsychological functioning among schizophrenic patients. Am. J. Psychiatry 153:(9)1178–1184, 1996.Crossref, Google Scholar

Lindamer, LA, and Jeste, DV. Estrogen and psychosis: Is there an association. International Psychiatry Today: 8(2);5–7, 1999.Google Scholar

Lindamer, LA; Lohr, JB; Harris, MJ; McAdams, LA; and Jeste, DV. Gender-related clinical differences in older patients with schizophrenia. J. Clin. Psychiatry 60:61–67, 1999Crossref, Google Scholar

Maurer, K, and Hafner, H. Methodological aspects of onset assessment in schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res. 15:265–276, 1995.Google Scholar

McNeil, TF. A prospective study of postpartum psychoses in a high-risk group. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 75:35–43, 1987.Crossref, Google Scholar

McNiel, DE; Greenfield, TK; Attkisson, CC; and Binder, R. Factor structure of a brief symptom checklist for acute psychiatric inpatients. J. Clin. Psychol. 45:66–72, 1989.Crossref, Google Scholar

Nausieda, PA; Koller, WC; Weiner, WJ; and Klawans, HL. Modification of postsynaptic dopaminergic sensitivity by female sex hormones. Life Sci. 25:521–526, 1979.Crossref, Google Scholar

Overall, JE, and Gorham, DR. The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale. Psychol. Rep. 10:799–812, 1962.Crossref, Google Scholar

Riecher, A; Maurer, K; Loffler, W; Fatkenheuer, B; van der Heiden, W; Munk-Jorgenson, P; Stromgen, E; and Hafner, H. Gender differences in age at onset and course of schizophrenic disorders. In: Hafner, H, and Gattaz, WF, eds. Search for the Causes of Schizophrenia. Berlin Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag, 1990. pp. 14–33.Google Scholar

Riecher-Rossler, A; Hafner, H; Dutsch-Strobel, A; Oster, M; Stumbaum, M; vanGulick-Bailer, M; and Loffler, W. Further evidence for a specific role of estradiol in schizophrenia? Biol. Psychiatry 36:492–495, 1994a.Crossref, Google Scholar

Riecher-Rossler, A; Hafner, H; Stumbalum, M; Maurer, K; and Schmidt, R. Can estradiol modulate schizophrenic symptomatology? Schizophr Bull. 20:203–213, 1994b.Crossref, Google Scholar

Riecher-Rossler, A, and Hafner, H. Schizophrenia and oestrogens—is there an association? Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 242:323–328, 1993.Crossref, Google Scholar

Seeman, MV Interaction of sex, age, and neuroleptic dose. Compr Psychiatry 24:(2)125–128, 1983.Crossref, Google Scholar

Seeman, MV, and Lang, M. The role of estrogens in schizophrenia gender differences. Schizophr. Bull. 16:185–194, 1990.Crossref, Google Scholar

Sherwin, BB, and Gelfand, MM. Sex steroids and affect in the surgical menopause: A double-blind, cross-over study. Psychoneuroendocrinology 10:(3)325–335, 1985.Crossref, Google Scholar

Spitzer, RL; Williams, JBW; Gibbon, M; and First, MB. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R-Patient Version (SCID-P, 411188). New York: Biometrics Research Department, New York State Psychiatric Institute, 1988.Google Scholar

Vahia, NS; Doongaji, DR; and Jeste, DV. Psychological medicine. In: Vakil, RJ, ed. Textbook of Medicine. Bombay: Association of Physicians of India, 1973. pp. 1476–1498.Google Scholar

v. Zerssen, D, and Koeller, DM. Klinische Selbstbeurteilungs-Skalen (KSb-Si) aus dem München er Psychhiatrischen Information System (PSYCHIS München) Manuale (cited in Riechler-Rosslei 1994). Weinheim: Beltz, 1976.Google Scholar

Van Hartesveldt, C, and Joyce, JN. Effects of estrogen on the basal ganglia. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 10:1–14, 1986.Crossref, Google Scholar

Wahl, OF, and Hunter, J. Are gender effects being neglected it schizophrenia research? Schizophr. Bull. 18:(2)313–317, 1992.Crossref, Google Scholar

Wechsler, D. WAIS-R Manual. Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale. Revised. New York: The Psychological Corporation, 1981.Google Scholar

Wieck, A; Kumar, R; Hirst, AD; Marks, MN; Campbell, IC; and Checkley, SA. Increased sensitivity of dopamine receptors and recurrence of affective psychosis after childbirth. Br. J. Med 303:613–616, 1991.Crossref, Google Scholar