Caring for “Difficult” Patients

There are patients, and there are patients. The difficult ones can be “demanding,” “noncompliant,” “whiny,” “entitled,” or “manipulative.” They can be too different from or too similar to the clinician, too seductive, too unclean, too smart, too fat, too thin, or too anxiety-provoking (McCarty and Roberts 1996). These patients require special attention because their care is very complex and because it invites significant ethical pitfalls. Recognizing what makes some patients “difficult,” understanding that “being difficult” is a clinical sign that warrants diagnostic interpretation, identifying the special ethical problems arising in the care of the difficult patient, and responding therapeutically are the key elements of ethically sound care for these challenging patients.

Recognizing “difficult” patients

It is often obvious who is, or is going to become, difficult. The patient who is perceived as “drug seeking,” the patient who is notorious for not taking his medications, the patient who engages in frequent self-mutilating behavior, the patient who seems to complain incessantly, the patient who threatens violence toward clinic staff, the patient who demands discharge from the hospital, the patient who is “just a personality disorder,” the patient who seems never to get better—these are the tough cases.

Sometimes the difficult patients can be more subtle in their presentation, however. The patient with a professional background who is utterly bright and engaging may end up being very difficult because he relates to the clinician as a friend from whom he asks for “favors” of prescriptions and laboratory tests. Similarly, the care of a patient who is also a clinician may become especially complex, for several reasons. For example, the patient may feel ashamed to reveal his health issues to a professional colleague. On the other hand, the caregiver may assume that the clinician/patient needs less support and reassurance than other patients. The caregiver may also fail to explore the possibility of self-diagnosis and self-prescribing by the clinician/patient. Other subtly difficult patients include individuals who omit or obscure important details when providing their histories and those who, along with their multiple medical and psychiatric symptoms, have multiple caregivers and multiple ongoing treatments.

Recognizing the difficult patient, then, involves identifying those individuals who are unusual in one of two ways. First, these patients may be difficult because of the special intensity of feelings (i.e., countertransference) they evoke by the clinical care team. For example, the patient whom one is especially tempted to “rescue,” to identify with, or to feel awed by is likely to be difficult. The victimized child, the physician/patient, the parish priest or local television news anchor, and people who look like the clinician’s Uncle Joe, Cousin Mary, or fifth grade teacher Mrs. Panturo may all fit into this category. Worse yet are patients who actually are the clinician’s Uncle Joe, Cousin Mary, or fifth grade teacher Mrs. Panturo—a phenomenon that is not unusual in some small towns or small health care systems. The patient who is also a litigation attorney may be a particularly intimidating—and therefore challenging—patient for any caregiver. The patient who has extraordinarily severe symptoms may be perceived as a difficult patient if he evokes feelings of distress or inadequacy in the clinician.

Other patients who present special problems are those whose experiences and illness processes are so tragic that they engender very powerful feelings of empathy and pain in their caregivers. These are the patients that clinicians carry with them, that make clinicians lose sleep, that clinicians always remember. The young mother dying of cancer, the military colonel who gradually succumbs to Alzheimer’s disease, the newly quadriplegic motorcycle accident victim, the survivor of wartime torture and trauma, the child who has been raped, and the college student who attempts suicide during his first psychotic break—these are the patients whom clinicians and clinical trainees may find very overwhelming and for whom they may find it extraordinarily difficult to provide effective care.

Patients who trigger unusually strong negative feelings (“gut reactions”) from members of the staff are also likely to present special challenges. These reactions may be due to the particular problematic feelings and conduct (e.g., anger, emotional lability, inconsistency, indifference, repeated suicide threats, self-mutilating or self-defeating behaviors) and psychological defenses (e.g., denial, projection, reaction formation) of the patients. They may also be related to uncomfortable or stigmatizing elements of a patient’s personal life history, such as the gang member who has served time in prison, the father whose careless driving resulted in the death of his child in an accident, or the pregnant woman who uses methadone. An unusual physical appearance—such as obesity, cachexia, exceptionally poor hygiene, congenital abnormalities, or regions of infection—may also trigger such feelings in caregivers. In some instances, the clinical care team will react to a given patient with disinterest and detachment. Although less overt than other “strong” negative reactions, such detachment likewise is an indicator of a problematic patient. The clinician who is well attuned to his or her own emotional responses, and those of the patient care team, will thus be well prepared to identify these difficult patients.

Beyond these affective factors that make a given patient unusual, a second cue in recognizing difficult patients is their atypical pattern of clinical service use. Patients who appear to seek prescription medications from many sources, to be overly insistent about clinic appointments and specialty referrals, or to obtain care repeatedly through emergency or urgent care facilities will come to be experienced as difficult patients by their care providers. Patients who appear to emphasize physical symptoms in mental health care settings and mental health symptoms in physical health care settings are particularly apt to stymie their caregivers. These patients often suffer from several comorbid physical and mental illness processes, giving rise to this kind of service utilization pattern. In contrast, the “underutilizers” of clinical services, such as patients who present late in the course of illness for treatment, demand discharge from the hospital against medical advice (AMA), do not take their medications, miss their scheduled appointments, or do not pursue necessary preventive care (e.g., parents who do not arrange for their children to receive appropriate vaccinations) will also pose special challenges and arouse strong emotions in caregivers. Such patients have been described as “help rejecters” (Robbins et al. 1988). Clinical syndromes may be the direct “cause” of these impaired care-seeking behaviors, as in the case of the social phobic patient or the negative-symptom-dominant schizophrenia patient with numerous “no shows” for clinic appointments. Similarly, the cardiac patient with an unrecognized alcohol problem may place his caregivers in clinical and ethical binds by insisting on leaving the hospital prematurely as he finds his withdrawal symptoms harder to tolerate.

Prevalence and attributes of “difficult” patients in medical and psychiatric settings

Because difficult patients take so many different forms, their relative numbers are difficult to estimate accurately. In medical settings, roughly one-sixth of patient encounters are perceived by clinicians as involving “difficult patients” (Jackson and Kroenke 1999). In one study of 500 patients, 15% were identified by their primary care providers as “difficult,” and these patients were more likely to have mental disorders, more than 5 somatic symptoms, more severe symptoms, poorer functional status, lesser satisfaction with care, and higher use of health services (Jackson and Kroenke 1999). In this study, physicians with more negative psychosocial attitudes as measured on the Physician’s Belief Scale were significantly more likely to experience patient encounters as difficult. In another study of 293 patients presenting for care in medical and surgical clinics, 22% were identified by consultants as leading to “difficult encounters,” primarily due to medically unexplained symptoms, coexisting social problems, and severe, untreatable illness (Sharpe et al. 1994). Encounter difficulty was associated with greater patient distress, less patient satisfaction, and heightened use of services.

A third study of 113 patients similarly found that difficult patients were characterized by psychosomatic symptoms, at least mild personality disorder, addiction, and major psychopathology (e.g., affective or anxiety disorders) but that demographic characteristics, provider characteristics, and most diagnoses were not correlated with a higher score on the Difficult Doctor-Patient Relationship Questionnaire (Hahn et al. 1994). In a study of 43 patients (21 identified as “difficult” and 22 controls), structured diagnostic evaluation revealed that a greater number of the difficult patients (7 of 21 vs. 1 of 22) had personality disorders. Five of the difficult patients with personality disorders met criteria for “dependent” personality, and none had had this psychopathology diagnosed previously (Schafer and Nowlis 1998). These findings echo those of a more recent study in which borderline personality disorder was found to be present in patients at an urban primary care clinic at four times the prevalence found in community populations (Gross et al. 2002). Half of these patients had received no mental health treatment, and 43% had not been accurately diagnosed in their primary care clinic. Other factors that may contribute to difficult patient encounters, such as perceived deception by patients, have been studied only minimally. However, one interesting study that assessed patient encounters of 44 family practice residents and attending physicians revealed that clinicians commonly doubted the truthfulness of their patients’ disclosures (19.5% and 8.7%, respectively) (Woolley and Clements 1997).

Analogous data have not been collected systematically in mental health care settings. Treatment resistance and nonadherence, very heavy utilization of mental health services, severe psychopathology due to personality disorders or psychotic disorders, and comorbid disease have been suggested as causes of difficult encounters in psychiatric settings (Hahn et al. 1996). The prevalence of difficult patient encounters is likely to be significantly higher in mental health care than in traditional medical settings, because of the specific nature of psychiatric illness and its care. Our patients have illnesses that affect behaviors, personal attitudes, mood symptoms, insight and motivation, and decision making. They have complex psychosocial issues, and the sicker patients often are poor and have limited abilities and/or opportunities to improve their socioeconomic circumstances. Patients with personality disorders who ultimately are referred for mental health treatment tend to be very seriously disturbed, and their care poses immense challenges. Patients with a constellation of medical and mental health symptoms who are referred for psychiatric consultation also tend to be very distressed, to pose diagnostic enigmas, or to have especially overwhelming psychosocial issues. For these reasons, mental health practitioners may feel that every patient encounter will potentially become a difficult one.

Understanding “difficult” as a clinical sign

The clinician’s first duty in the care of the difficult patient is to understand that the aspects of the patient’s presentation that make him or her “difficult” are, in essence, clinical signs—that is, observable manifestations of the patient’s underlying health and of factors affecting his or her health status. In other words, there is a differential diagnosis that accompanies “being difficult.” The patient who is threatening in his behavior toward clinic staff may in fact be experiencing irritability, fear, and psychotic symptoms early in the course of a manic episode. The patient could also be head-injured, delirious, or intoxicated. The frustratingly “noncompliant” patient with unremitting symptoms may hold different religious beliefs about acceptable healing practices, may have experienced unpleasant side effects of pills, may not have insight about the need for treatment, or, alternatively, may not have the resources to purchase prescription medications or to obtain transportation for clinic appointments. Moreover, because traumatized individuals often tend to relive their past experiences in the context of their current lives, the patient who behaves seductively in the therapeutic relationship may have been sexually exploited in the past. Rather than expressing authentic romantic feelings for the clinician, this patient is manifesting his or her core psychological issues for the clinician, who has the duty to understand this clinical phenomenon. Such “difficult” behaviors should be understood in a dispassionate, nonjudgmental manner. They are observable clinical “signs.”

Clarifying the reasons why patients appear to be undermining their own health and health care is therefore an important responsibility of the clinician. Behavioral cues of patients should be explored and interpreted clinically, not superficially or too concretely. Just as the seductive patient should not be taken at face value, the angry patient also should not be viewed as intentionally “acting out” in order to “create trouble.” In sum, all elements of the patient’s presentation are important clinical data, and clinicians must remain within their professional roles and uphold their professional duties when dealing with the challenges of the difficult patient.

Identifying ethical pitfalls in the care of difficult patients

Difficult patients are at risk of receiving care that deviates from usual ethics standards in several respects. First, therapeutic abandonment of patients is much more likely when they are unlikable, frustrating, apparently noncompliant, extraordinarily tragic, or otherwise atypical. Efforts made to preserve the therapeutic alliance and to obtain appropriate informed refusal of treatment with a patient who is “medication seeking” or “demanding AMA discharge” may be minimal in many circumstances, for instance. The caregiver may pay less attention to carefully diagnosing the multiple clinical problems of the patient whose interpersonal manner and use of health services are seen as “inappropriate.” Important medical issues that merit exploration may be dismissed as “psychiatric,” as, for example, in the situation of a medical student with undiagnosed Crohn’s disease whose symptoms are attributed to exam-related stress and poor coping skills. Gradual, quiet disengagement from the persistently suffering patient, although not legally problematic, is another subtle form of therapeutic abandonment that may occur.

Second, professional boundaries may erode in the care of difficult patients, resulting in ethically compromised care. When patients are difficult because they resemble their caregivers in terms of having similar backgrounds, professions, or interests, the clinician and patient may begin relating to one another in a manner more congruent with a friendship than a professional relationship—for example, the clinician may disclose aspects of his or her personal life, accept financial advice, or make social plans in the course of talking with the patient. Personal-professional boundaries are crossed in such situations, and the ethical foundation of the relationship—trust and absolute dedication to the well-being of the patient—may be seriously jeopardized. Informed consent processes may suffer, because these clinicians may provide insufficient information about clinical care alternatives or may suggest only those treatment options that they personally would consider. Caregivers who overly identify with their patients may also be tempted to document clinical issues inaccurately or to not comply with legal mandatory-reporting duties when stigmatizing issues arise in such cases. Splits within treatment teams may occur as some clinicians become closer to difficult patients for whom they have warmer personal feelings and other members of the team do not. Clinicians may act unprofessionally in subtle ways by providing undocumented prescriptions or samples of medications. They may also act unprofessionally in more overt ways by becoming intimately involved with patients who give sexualized behavioral cues or who are otherwise vulnerable to the approaches of a “powerful” person.

Third, confidentiality breaches may occur when caregivers discuss the difficult patient’s case in relatively public settings, a behavior fueled by strongly held and hard-to-contain feelings. The temptation to discuss the aggravating patient about whom the clinical team has passionate complaints is great, but it is also an issue when, for example, the patient is a celebrity or a celebrity’s child who suffers from serious mental illnesses and/or substance problems. It is often difficult for clinicians to manage their natural curiosity, even voyeurism, and their desire to discuss the patient with colleagues and friends in such cases.

The challenges in caring for difficult patients therefore affect every ethically important aspect of clinical practice. Maintaining attentiveness to the clinical signs and symptoms of the patient, building and sustaining the therapeutic alliance, respecting the autonomy of the patient through sound informed consent and refusal-of-treatment processes, upholding the law, and maintaining appropriate confidentiality safeguards may all be adversely affected.

Responding therapeutically

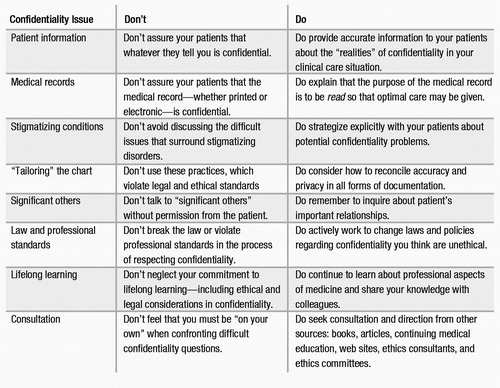

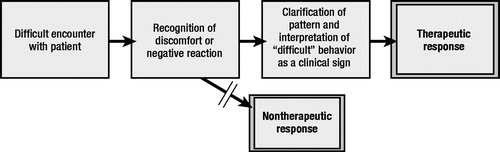

Ensuring that difficult patients receive clinically and ethically sound care is no small task (Table 1). The most critical step in responding therapeutically is to recognize the discomfort and problems that difficult patients generate as a clinical sign (Figure 1). Monitoring one’s own reactions and responding with professionalism and thoroughness to the symptoms and behavioral presentations of these special patients are the keys to providing good care in potentially taxing clinical situations. Responding therapeutically may entail building a sense of empathy for the unlikable or otherwise off-putting patient; it may entail assuming a more professional, more objective stance with the especially charming or intriguing patient.

Several core elements of treatment for the difficult patient have been proposed by experienced clinicians (Drossman 1978; McCarty and Roberts 1996). These include maintaining a nonjudgmental interest in the patient’s reports; keeping personal and professional roles “straight”; reflecting on one’s own attitudes and biases; taking a complete history and accepting (not arguing with or discounting) the patient’s symptoms; performing or referring the patient for a thorough physical examination; avoiding patronizing or inappropriate reassurance (“it’s just stress”); refraining from intervening with medications or aggressive treatments prematurely; setting up regular visits and being interpersonally “predictable” and consistent; remaining alert for new developments; clearly presenting therapeutic options to the patient; preparing for a protracted course of treatment; communicating all findings and treatment plans to the clinical care team before, during, and after their discovery or implementation; and educating oneself about the biopsychosocial aspects of the patient’s disease process.

It is also important to accept one’s own limitations in dealing with the countertransference and ethical issues presented by difficult patients and to seek out appropriate professional venues for clarifying these issues. For example, thoughtful discussions with members of the clinical care team about strategies for responding to the frustrations encountered in a particular patient’s care may be highly valuable. Comparing and double-checking one’s own perceptions with those of trusted team members will be a helpful step in this process. Seeking out additional clinical, ethical, and legal expertise from knowledgeable colleagues and supervisors is especially important. Use of humor when discussing highly problematic patients with clinical team members is controversial from an ethical perspective. Although perhaps not optimal, humor is often inevitable in caring for difficult patients and can be put to constructive use in illuminating the more troublesome features of the patient’s case and highlighting the powerlessness or frustration felt by members of the clinical team. So long as there are ample manifestations of respect toward the patient and faithfulness to the ethical principles of beneficence and nonmaleficence in the patient’s care—and a thoughtful discussion of the treatment issues—the team leader may interpret the humor in a manner that contributes positively to the “multiproblem” patient’s care.

One final consideration in this challenging process is to examine the lessons learned in the course of caring for difficult patients—the unexpected diagnosis of the patient, the unexpected strengths of a team member, the unexpected impact of a miscommunication, the unexpected community resource, the unexpected resilience of the caregiver. Paying attention to these valuable lessons will help address the natural exhaustion felt by many clinicians, and it will also help expand their repertoire of skills and abilities for their next patient encounter, which may or may not pose special difficulties.

Case scenarios

A young man with self-mutilating behavior presents to the psychiatric emergency room, having chewed and swallowed glass after being stopped by police for driving while intoxicated.

A senior medical student approaches his supervisor, an attending physician, for antidepressant medications. He states that he is under tremendous stress and does not wish to seek formal care because he “can’t get a mental health record” if he wants to get into a residency program.

A young woman with a history of sexual trauma and abnormal menstrual bleeding asks her primary care physician to set up a gynecological examination. Although she has missed her last two appointments, the physician arranges for an appointment for later in the week. She arrives late, says “I’m pregnant,” appears distraught, and tells the nurse that she “just took a lot of pills.” She is taken to the emergency room.

An elderly man who ordinarily lives in a motel for transients in a poor neighborhood presents to the psychiatric emergency room on a cold winter night, with all of his possessions in a large plastic bag. He demands admission to the hospital, stating that he will kill himself if he is sent to a shelter. The staff note that the patient’s pattern is to come to the ER toward the end of the month, when he has run out of money and is unable to stay at his motel.

A recently retired man with mild hypertension, arthritis, and a family history of cancer (both of his parents died of cancer) seems to fill every appointment with a recitation of complaints and worries. Each time the physician tries a different treatment, the patient returns, complaining of its lack of efficacy. The patient frequently discontinues his medications prematurely because of “side effects.” He makes frequent calls to the doctor’s office and is “known” for his pattern of frequent visits to the urgent care and walk-in clinics.

A veteran with comorbid mental and addictive illnesses is admitted to a psychiatric inpatient unit. Four days into his hospitalization, he is allowed to go on a walk with his brother and sister-in-law on the grounds of the VA facility. He returns 10 minutes late, walking unsteadily and speaking rapidly and in an animated fashion.

|

Table 1. Steps in Managing Difficult Patientsa

Figure 1. Responding Therapeutically to the “Difficult” Patient

Drossman DA: The problem patient: evaluation and care of medical patients with psychosocial disturbances. Ann Intern Med 88:366–372, 1978Crossref, Google Scholar

Gross R, Olfson M, Gameroff M, et al: Borderline personality disorder in primary care. Arch Intern Med 162:53–60, 2002Crossref, Google Scholar

Hahn SR, Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, et al: The difficult patient: prevalence, psychopathology, and functional impairment. J Gen Intern Med 11:1–8, 1996Crossref, Google Scholar

Hahn SR, Thompson KS, Wills TA, et al: The difficult doctor-patient relationship: somatization, personality and psychopathology. J Clin Epidemiol 47:647–657, 1994Crossref, Google Scholar

Jackson JL, Kroenke K: Difficult patient encounters in the ambulatory clinic: clinical predictors and outcomes. Arch Intern Med 159:1069–1075, 1999Crossref, Google Scholar

McCarty T, Roberts LW: The difficult patient, in Medicine: A Primary Care Approach. Edited by Rubin RH, Voss C, Derksen DJ, Gateley A, Quenzer RW, Coss C. Philadelphia, PA, WB Saunders, 1996, pp 395–399Google Scholar

Robbins JM, Beck PR, Mueller DP, et al: Therapists’ perceptions of difficult psychiatric patients. J Nerv Ment Dis 176:490–497, 1988Crossref, Google Scholar

Schafer S, Nowlis DP: Personality disorders among difficult patients. Arch Fam Med 7:126–129, 1998Crossref, Google Scholar

Sharpe M, Mayou R, Seagroatt V, et al: Why do doctors find some patients difficult to help? Q J Med 87:187–193, 1994Google Scholar

Woolley D, Clements T: Family medicine residents’ and community physicians’ concerns about patient truthfulness. Acad Med 72:155–157, 1997Crossref, Google Scholar