Patient Management Exercise A Person-Centered Approach to Treatment

Abstract

This exercise provides a practice-based example of the principles and practice of person-centered therapy described in this issue of FOCUS. Answer the questions below, on the information provided, making your decisions taking the person-centered approach.

Questions are presented at “decision points” that follow sections that give information about the case. One or more choices may be correct for each question; make your choices on the basis of the history provided. Read all of the options for each question before making any selections.

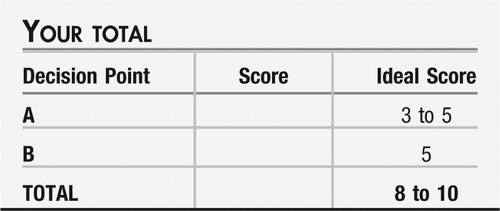

For the exercise in this issue of FOCUS, the points are scaled from responses most in line with the principles and practice of Person-Centered Therapy (+3) to those neutral or typical of conventional practice (0), and to ideas that are more provider-directed in nature (−2). At the end of the exercise, you will add up your points to obtain a total score.

CASE VIGNETTE PART 1

Mark is 24-year-old single employed male who was referred by his psychologist and presented to you with the remark: “Well, I'm here for depression. I'm pretty sure my current medication [fluoxetine 60 mg daily] is no longer working.” Two weeks earlier, his mood had been “abysmal, hopeless;” but today he reported “it's ok now.” He acknowledged that there has been a long-standing cyclical nature to his moods. He reported to you that at bedtime, he usually experiences about an hour of his “mind going going going,” and then he will sleep fitfully for 10–11 hours. He described problems maintaining interests, which were reduced overall at present. Feelings of guilt were also endorsed. Concentration, he was careful to report, was intact, except for a problem making decisions: he described that he “nearly had a panic attack” trying to choose which box of breakfast cereal to buy a few days ago. He reported that he eats mechanically, on a schedule, with little enjoyment; his weight has been stable. When you asked about psychotic symptoms, he reported that in childhood, he occasionally heard a woman's voice call his name. When asked about paranoid ideation, he wondered aloud if “fate is plotting against me.” He described having a passive death wish and admitted to having suicidal ideation in the past, with a plan then to “make it look like an accident” and prevent his body from being found. No homicidal ideation has ever been present. Screening for anxiety, he shared, “I worry mostly about running out of time” and “I have never liked being alone in the dark.” He has been seeing a psychotherapist for 2 years; he is unsure that this is helping him much.

You and he completed a validated Mood Disorder Questionnaire; he endorsed  behaviors, suggestive of probable bipolar disorder. When asked about his experience of anger, he noted, “I've never gotten to the point of shouting at someone. … I usually don't express or deal with my upset. … It's hard to tell if I'm angry. I learned not to get angry as a child—it was punished.” He reported his IQ was greater than 140; it was clear that he is intellectually gifted in this conversation. He has never dated regularly, although he has asked some girls out. Caffeine use was described “as little as possible … it makes me feel tense and jittery.” He reported that 6 months ago he had “quite a bit of alcohol,” which resulted in suicidal despair. He reported no other drug use.

behaviors, suggestive of probable bipolar disorder. When asked about his experience of anger, he noted, “I've never gotten to the point of shouting at someone. … I usually don't express or deal with my upset. … It's hard to tell if I'm angry. I learned not to get angry as a child—it was punished.” He reported his IQ was greater than 140; it was clear that he is intellectually gifted in this conversation. He has never dated regularly, although he has asked some girls out. Caffeine use was described “as little as possible … it makes me feel tense and jittery.” He reported that 6 months ago he had “quite a bit of alcohol,” which resulted in suicidal despair. He reported no other drug use.

Decision Point A:

At this point, what would you offer this patient as your therapeutic relationship starts? (Select all options you might choose.)

| A1._____ | Taper fluoxetine to discontinuation and introduce another antidepressant. |

| A2._____ | Prescribe a mood stabilizer. |

| A3._____ | Introduce a 5-minute meditation, in which, with eyes closed, attention is concentrated on an internal experience, such as love or hope. |

| A4._____ | Monitor alcohol and drug use. |

| A5._____ | Offer that he take the Temperament Character Inventory (TCI), either with a paper copy or on a computer. |

CASE VIGNETTE PART 2

Your patient returns sometime later: “I'm doing ok. … I'm cautious to say things are getting better. In the past, things would look good, but then change for the worse sometimes.” Mood was endorsed as “middle of the road.” He reported sleeping better and that his interests were “a little” improved. Some low feelings persist, but they were not as “heavy” as previously. Energy was “unchanged.” Appetite was “the same,” he has lost 13 pounds by not eating refined carbohydrates. He reported he was “hardly irritable anymore.” No auditory hallucinations were endorsed, although he still felt “the fates” were out to get him. An occasional passive death wish was endorsed but no suicidal ideation or plans. He drank once since his last visit: 6–8 shots of tequila one evening, when he was “down;” he expanded that he did this just to “remind” himself that he doesn't like it and it doesn't work to help him feel better. He had been seeing his psychologist weekly, but it has actually been a month since their last appointment

He completed the TCI and at this visit you took the opportunity to review the results with him:

| Temperament | Novelty Seeking: 15th percentile (low) Harm Avoidance: 99th percentile (high) Reward Dependence: 45th percentile (average) Persistence: 55th percentile (average) |

| Character | Self-Directedness: 1st percentile (low) Cooperativeness: 65th percentile (high average) Self-Transcendence: 20th percentile (low) |

As to Temperament indices, you commented to him that the low Novelty Seeking score matched your impression of his comfort with routine and rules (e.g., eating on schedule). The high Harm Avoidance value was what you might expect in someone with chronic and somewhat refractory depression and anxiety and with problems making decisions. The Reward Dependence in the average range surprised you, given his chosen social isolation, so you looked at the performance-based scores, which were derived from how the individual responds—and found a Reward Dependence score of the 5th percentile.

Shifting your discussion to indices of Character, his low Self-Directedness was recognized as a basis for chronic depression and irritability and hinted at the presence of a personality disorder. This also supported his vulnerability to cycling in his moods. As another instance, you reminded him of how he has had episodes of drinking alcohol without enjoyment. Drinking alcohol without actually liking it fits with having low Self-Directedness. You interpreted the high average Cooperativeness as indicating his capacity to be tolerant and helpful. Low Self-Transcendence suggests that a person is more concrete and materialistic in thinking; you offered as an example how he had once complained that he “didn't see the point” of poetry.

Decision Point B:

With these concepts of who he is as a person and some of the particular difficulties he encounters in his life, he reports that he is somewhat better. Augmentation of fluoxetine with a mood stabilizer has also helped manage symptoms. What would you offer him next?

| B1._____ | Continue current regimen. Plan interim follow-up appointment. |

| B2._____ | Suggest he find a leisure pursuit in which he can lose track of time (that is, to cultivate self-forgetfulness, the first stage of Self-Transcendence). |

| B3._____ | Invite reflection, curiosity about himself and his experiences. |

| B4._____ | Encourage him to acquire a pet to build reward dependence. |

| B5._____ | Prescribe low-dose atypical antipsychotic medication. |

ANSWERS: SCORING, RELATIVE WEIGHTS, AND COMMENTS

Decision Point A:

| A1._____ | Taper fluoxetine. (−1) A reasonable current practice but not coming out of the Person-Centered Therapy approach being emphasized here. |

| A2._____ | Prescribe a mood stabilizer. (−2) Although this is entirely a reasonable intervention, it is an overtly directive response, emphasizing the professional expertise of the provider and minimizing the contribution of the particular person of the patient. This will be especially necessary when an individuals are deeply distressed by the symptoms of their mental illness and have restricted personal wherewithal to move toward well-being. One may need to stabilize them, recover function, and then help them to appreciate their own strengths, progressing into a more balanced and evenly regulated self-with the principles of Person-Centered Therapy. |

| A3._____ | Introduce a meditation. (+3) Clearly a Person-Centered Therapy response. The aim of this exercise is to offer a setting for the first stage of self-aware consciousness. |

| A4._____ | Monitor substance use. (0) A more directive response, shifting the balance of power in the therapeutic relationship more toward the psychiatrist. Again, at times, our patients need a more supportive approach. It is our best service to them to know when to “graduate” them to more independent thinking. |

| A5._____ | Offer the TCI. (+2) Partly a Person-Centered Therapy response. This personality assessment tool will provide you and he with a description of himself, facilitating a greater understanding and the basis for validation and rapport. The possibility of transformation requires the recognition of the currently held position before authentic personal growth can occur. |

Decision Point B:

| B1._____ | Continue current regimen. (0) A neutral intervention, considered to be typical and reasonable current practice but not coming out of the Person-Centered Therapy approach being emphasized in this issue of FOCUS. |

| B2._____ | Suggest leisure pursuits. (+2) Partly a Person-Centered Therapy response. This intervention will give him the opportunity to build Self-Directedness, in that he will have to decide for himself what activity he would like to do to complete the assignment. Self-forgetfulness is the first stage in the development of Self-Transcendence, which needs to be cultivated to achieve a greater sense of overall well-being and satisfaction in life. The idea is to find a pastime in which he becomes so absorbed as to lose track of time; this may be challenging given his low Novelty Seeking (he would prefer a well-defined assignment with rules and a clear endpoint, for example, “Do a 500-piece jigsaw puzzle”). |

| B3._____ | Invite reflection. (+3) Clearly a Person-Centered Therapy response. With the patient showing some improvement in symptoms of depression, anxiety, and irritability, it is a reasonable time to encourage exploration of the principles of Person-Centered Therapy: letting go, working in the service of others, growing in awareness and increasing knowledge in the processes of thought. |

| B4._____ | Recommend a therapeutic pet. (−1) A more directive response and showing some “thinking outside the box,” but this again is using the physician's judgment in lieu of the patient's to suggest an activity. One must be careful in Person-Centered Therapy, because an individual with low Self-Directedness will look to the therapist anxiously for guidance, and one's natural tendency might be to offer counsel or advice. The optimal therapeutic benefit will be derived if the therapist can be supportive but not overtly directive, allowing the person to discover and declare his own inclinations. (Obtaining a plant or a pet could help an individual develop Self-Directedness and may contribute to promoting Reward Dependence.) |

| B5._____ | Prescribe a low-dose atypical antipsychotic. (−2) Although this could be an adjustment of the patient's medication regimen, it is another overtly directive response, emphasizing the professional expertise of the provider and minimizing the contribution of the particular person of the patient. |

|

Cloninger CR: Feeling Good: The Science of Well-Being. New York, Oxford University Press, 2004 Google Scholar

Cloninger CR, Przybeck TR, Svrakic DM, Wetzel RD: The Temperament Character Inventory (TCI): A Guide to Its Development and Use. St. Louis, MO, Center for Psychobiology of Personality, 1994 Google Scholar

Hirschfeld RMA, Williams JBW, Spitzer RL, Calabrese JR, Flynn L, Keck PE, Lewis L, McElroy S, Post RM, Rapport DJ, Russell JM, Sachs GS, Zajecka J: Development and validation of a screening instrument for bipolar spectrum disorder: the Mood Disorder Questionnaire. Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157:1873–1875 Crossref, Google Scholar

Know Yourself DVD Series. St. Louis, MO, Anthropedia Foundation. http://www.anthropediafoundation.org Google Scholar

Wong KM: Unpack your stuff with the TCI, in Stop Clutter From Stealing Your Life: Discover Why You Clutter & How You Can Stop, rev. ed. Edited by Nelson, M. Franklin Lakes, NJ, The Career Press, 2008, pp 149–153 Google Scholar