Clinical Use of Telemedicine in Child Psychiatry

Abstract

The national shortage of child psychiatrists has left many children without access to treatment. Telepsychiatry can extend the reach of child psychiatry by providing consultative care to children at a distance. The authors provide a definition of telepsychiatry, a review of the limited published child research in the area, and a child telepsychiatry clinic model. The value of child telepsychiatry is emphasized, as well as the need for standardized practice and research.

Despite the need for expanding child psychiatric services, telepsychiatry has been used primarily in adult psychiatric practice. Efforts to use this medium in child psychiatry are limited. There are fewer than 8,000 child psychiatrists in the United States and a limited number in child psychiatry fellowship training; the Surgeon General estimates that less than 20% of the 13.7 million children and adolescents in need of treatment for mental illness receive care (1). Similar to adult rates, 20% of children and adolescents in the United States are estimated to have emotional and behavioral disorders. Suicide was the third leading cause of death among children aged 10–24 in 2004 (2), and there is evidence of even higher suicide rates among children in rural areas (3, 4). Calloway et al. (5) noted several articles reporting that rural youth receive fewer mental health services than urban youth. Almost three-fourths of smaller rural counties with populations of 2,500–20,000 lack a psychiatrist and 95% lack a child psychiatrist. Consequently, children in these regions with serious mental health problems are among the most disadvantaged in receiving care (6).

The use of videoconferencing technology gives specialists a means of providing care at a distance. Its application would improve the quality of treatment, reduce its cost, and clearly create accessibility for patients (7). Telemedicine applied to psychiatry is defined as the use of electronic communication and information technologies in order to provide or support its application of clinical psychiatric care at a distance (2). Videoconferencing technologies enables a real-time patient and a mental health professional to simultaneously connect with one or more primary sites and one or more secondary sites for a diagnostic, therapeutic, or educational direction (9).

A review of the literature revealed 33 articles relevant to child telepsychiatry. Eight published case studies (5–12) demonstrated that telepsychiatry can benefit children, adolescents, and their families. In three studies comparison groups were used to measure the reliability of interactions in face-to-face versus telepsychiatry consultations. Myers et al. (13) found that there were no significant differences between a direct care and a telepsychiatry treatment group. There were no significant differences in the two randomized controlled trials comparing face-to-face with telepsychiatry diagnosis and treatment outcomes (14, 15).

There have been several published child telepsychiatry program descriptions. However, none of these provide enough specific data and detail about the telepsychiatry clinics in order to replicate them for clinical or research purposes. Programs have been used in hospitals, schools (9, 11, 15, 17), forensic settings (21), and youth correctional facilities (25). Eighteen articles evaluated satisfaction with clinical care, services, education, and technology offered through telepsychiatry (7, 14, 15, 18, 20, 21, 25–36).

Child telepsychiatry systems have been implemented for a variety of educational purposes. Reports of successful uses in continuing professional education and in-service training were established (17, 20, 21, 31, 37). Interactive sessions were also implemented, focusing on current clinical cases for which supervision or consultation was also provided through videoconferencing (on an ongoing or as-needed basis) (16, 27, 30, 35, 38). Four comprehensive articles pertained to child and adolescent psychiatry (30, 39–41). Three of these authors made recommendations for future research and programmatic design. Alessi (39) concluded that more standardized empirical research studies and empirically validated measures are needed. Boydell et al. (40) created a framework to guide the development of telepsychiatry programs.

A TELEPSYCHIATRY MODEL

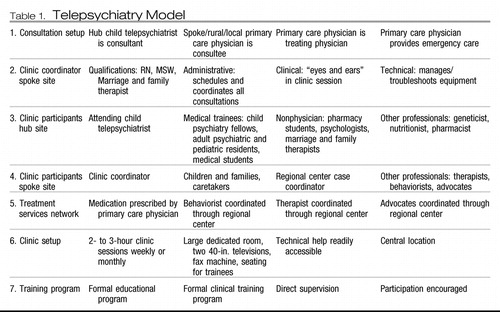

Many telepsychiatry clinics fail or fall short of success. We highlight seven components that are critical for sustainability (Table 1).

| 1. | Telepsychiatrists as collaborative consultants to primary care rural doctors. “Hub site” telepsychiatrists work as consultants and do not provide direct care. All treatment is local, including emergency treatment. The primary care doctor, or consultee, is not present during the consultation but will implement treatment recommendations for medications and medical or laboratory tests. He or she may phone the telepsychiatrist with any questions or concerns. The telepsychiatrist continues to consult with the patient virtually while actively monitoring progress in follow-up visits. | ||||

| 2. | Consultation input: Multidisciplinary data provided for each consultation. The “spoke site” clinic coordinator gathers critical information from multiple sources for all clinic visits, starting with the evaluation. Without this information including report cards, individual educational plans (IEPs), laboratory tests, psychological testing, therapist reports, teacher progress notes, and symptom rating scales, the hub child psychiatrist will not have necessary data to evaluate progress. | ||||

| 3. | Interactive multiple participant consultation. This consultation often includes four or five people at both the hub and spoke sites, creating a large treatment team that collaborates with the parent. The clinic coordinator manages the spoke clinic and helps with on-site issues such as escalating behavior. In congruence with the finding of Hilty et al. for patients (42, 43), we have found that by hearing the process of the treatment team creating a plan helps parents feel more in control and more comfortable with the telepsychiatrist's recommendations. The parents gain insight into the thought process behind decisions and become more informed about their child's treatment and problem. | ||||

| 4. | Consultation outpatient: Treatment network. The telepsychiatrist usually recommends medical, psychopharmacological, behavioral, psychological (for child and family), treatment as well as school and developmental interventions for the child. The spoke site must coordinate with providers who can supply specific services and are willing to work with the clinic. | ||||

| 5. | Teleclinic coordinator with both administrative and clinical roles. The spoke site clinical coordinator must have expertise with technology and clinic administration, participate in clinics, and coordinate follow-up care and triage issues that arise. Because of the limits to what the telepsychiatrist can see, the coordinator is the in-session eyes and ears, observing the patient and actively directing the psychiatrist to things he or she cannot observe directly. | ||||

| 6. | Clinic setup. Clinics must occur in structured blocks of at least 2 hours. | ||||

| 7. | Education: training of professionals. Trainees can attend telepsychiatry clinics with less intrusion than families would experience in a face-to-face consultation. Trainees can participate easily and actively learn from direct rather than “after the fact” supervision. | ||||

|

Table 1. Telepsychiatry Model

CONCLUSION

Child telepsychiatry needs empirical psychometrically sound research studies, well-developed clinic protocols, and a collaborative consultation treatment model for future growth. Psychiatric consultation using telepsychiatry, as described in our model, is different from the traditional medical model of psychiatric treatment. Teleclinics create a new clinic team involving a coordinator who participates directly in the clinics and an off-site local primary care doctor. These clinics require greater parent involvement and education. They require greater overall structure for success. The rural primary care doctors enjoy the opportunity to broaden their ability to use psychiatric medications and to see their patients improve. The clinics provide an excellent opportunity for psychiatric training. The telepsychiatrists find this multidimensional clinic interesting and stimulating, providing an opportunity to see patients rarely seen in local clinics. Because of the lack of adequate diagnosis before consultation, cases can have added complexity. From our telepsychiatry chart review, we found that more than half of the new patients seen had incorrect diagnoses and medications but the conditions of these patients improved after they were seen in our clinic. We have experienced an extremely high treatment compliance rate and a low no-show rate, compared with face-to-face consultations, which we believe results from the strengths of our model.

RESEARCH

Child telepsychiatry has not kept pace with the general field of child psychiatry for which there has been a large increase in reliable standardized methodologies for assessment and characterization of mental and emotional disorders. Scientific standards including randomized controlled studies that incorporate test-retest and inter-rater reliability must be adopted (39). In addition, studies need to be longitudinal and have larger subject pools that focus on the impact of telepsychiatry on different diagnoses, treatment, and specific outcomes. This information will show us which disorders can best be treated and what treatment methodologies can be used in telepsychiatry. Also, research can further help us identify the important differences between face-to-face versus telepsychiatric psychiatric consultations.

STANDARDS FOR TELEPSYCHIATRY

The quality of care of telepsychiatry should compare to that for face-to-face consultations with the high standard of conventional child and adolescent psychiatry practice as the optimal reference point in the field (44). Psychiatry needs to establish its own telepsychiatry protocols. Standards will help address issues of liability and emergency care, which are particularly important in this area. Only with an appropriate and sound clinical child telepsychiatry set up can the optimal care be provided as a base for high-quality research.

CLINICAL CARE

Telepsychiatry can extend the reach of urban child psychiatrists to the rural youth in need by providing evaluations and follow-up consultations. The combination of treating, training, and teaching, which is our clinic mission, will help child telepsychiatry reach its greatest potential.

1 American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry: Child and Adolescent Psychiatrists Champion Child Healthcare Crisis Relief Act, 2007. http://www.aacap.org/cs/2007_press_releases/child_and_adolescent_psychiatrists_champion_child_healthcare_crisis_relief_actGoogle Scholar

2 American Psychiatric Association: Resource Document on Telepsychiatry via Videoconferencing, 2006. http://www..aacap.org/cs/2007_press_releases/child_and_adolescent_psychiatrists_champion_child_healthcare_crisis_relief_actGoogle Scholar

3 Eberhardt MS, Ingram DD, Makuc DM: Urban and Rural Health Chartbook: Health, United States, 2001. Hyattsville, Md, National Center for Health Statistics, 2001Google Scholar

4 Hartley D, Bird D, Dempsey P: Rural mental health and substance abuse, in Rural Health in the United States. Edited by Ricketts TC. New York, Oxford University Press, 1999, pp 159– 179Google Scholar

5 Calloway M, Fried B, Johnsen M, Morrissey J. Characterization of rural mental health service systems. Journal of Rural Health. 1999; 15 ( 3): 296– 306Crossref, Google Scholar

6 Holzer CE, Goldsmith HF, Ciarlo JA. Chapter 16: Effects of rural-urban country type on the availability of health and mental health care providers. Mental Health, United States. Washington, DC: DHHS Publishing 1998; 204– 13Google Scholar

7 Goldfield GS, Boachie A: Delivery of family therapy in the treatment of anorexia nervosa using telehealth. Telemed J E Health 2003; 9: 111– 114Crossref, Google Scholar

8 Hilty D, Sison J, Nesbitt T, Hales R: Telepsychiatric consultation for ADHD in the primary care setting. J Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2000; 39: 15– 16Crossref, Google Scholar

9 Miller T, Kraus R, Kaak O, Sprang R, Burton D: Telemedicine: a child psychiatry case report. Telemed J E Health 2002; 8: 139– 148Crossref, Google Scholar

10 Paul LA, Gray MJ, Elhai JD, Massad PM, Stamm BH: Promotion of evidence-based practices for child traumatic stress in rural populations: identification of barriers and promising solutions. Trauma Violence Abuse 2006; 7: 260– 273Crossref, Google Scholar

11 Rendon M: Telepsychaitric treatment of a school child. J Telemed Telecare 1998; 4: 179– 182Crossref, Google Scholar

12 Savin D, Garry MT, Zuccaro P, Douglas N: Telepsychiatry for treating rural American Indian youth. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Pyschiatry 2006; 45: 484– 488Crossref, Google Scholar

13 Myers K, Sulzbacher S, Melzer S: Telepsychiatry with children and adolescents: are patients comparable to those evaluated in usual outpatient care? Telemed J E Health 2004; 10: 278– 285Crossref, Google Scholar

14 Elford R, White H, Bowering R, Ghandi A, Maddiggan B, St John K, House M, Harnett J, West R, Battcock A: A randomized, controlled trial of child psychiatric assessment conducted using videoconferencing. J Telemed Telecare 2000; 2000: 73– 82Crossref, Google Scholar

15 Nelson E, Barnard M, Cain S: Treating childhood depression over videoconferencing. Telemed J E Health 2003; 9: 49– 55Crossref, Google Scholar

16 Broder E, Manson E, Boydell K, Teshima J: Use of telepsychiatry for child psychiatric issues: first 500 cases. Can Psychiatr Assoc 2004; 36: 11– 15Google Scholar

17 Bryant B: Telepsychiatry gets good reception with Taxes High School students. Psychiatr News 2007; 42: 22Google Scholar

18 Dossetor D, Nunn K, Fairley M, Eggleton D: A child and adolescent psychiatric outreach service for rural New South Wales: a telemedicine pilot study. J Paediatr Child Health 1999; 35: 522– 529Crossref, Google Scholar

19 Ermer D: Experience with a rural temperament clinic for children and adolescents. Psychiatr Serv 1999; 50: 260– 261Crossref, Google Scholar

20 Fahey A, Day N, Gelber H: Tele-education in child mental health for rural allied health workers. J Telemed Telecare 2003; 9: 84– 88Crossref, Google Scholar

21 Miller TW, Burton DC, Hill K, Luftman G, Veltkemp LJ, Swope M: Telepschiatry: critical dimensions for forensic services. J Am Acad Psychiatry 2005; 33: 536– 546Google Scholar

22 Pammer W, Haney M, Wood B, Brooks RG, Morse K, Hicks P, Handler EG, Rogers H, Jennett P: Use of telehealth technology to extend child protection team services. Pediatrics 2001; 108: 584– 590Crossref, Google Scholar

23 Staller J: Psychiatric nurse practitioners in rural pediatric telepsychiatry. Psychiatr Serv 2006; 57: 137– 138Crossref, Google Scholar

24 Sulzbacher S, Vallin T, Waetzig EZ: Telepsychiatry improves paediatric behavioural health care in rural communities. J Telemed Telecare 2006; 12: 285– 288Crossref, Google Scholar

25 Myers M, Valentine J, Morganthaler R, Melzer S: Telepsychiatry with incarcerated youth. J Adolesc Health 2006; 38: 643– 648Crossref, Google Scholar

26 Blackmon L, Kaak H, Ranssen J: Consumer satisfaction with telemedicine child psychiatry consultation in rural Kentucky. Psychiatr Serv 1997; 48: 1464– 1466Crossref, Google Scholar

27 Burton D, Stanley D, Ireson C: Child advocacy outreach: using telehealth to expand child sexual abuse services in rural Kentucky. J Telemed Telehealth 2002; 8 ( suppl 2): 10– 12Google Scholar

28 Elford DR: A prospective satisfaction study and cost analysis of a pilot child telepsychiatry service in Newfoundland. J Telemed Telecare 2001; 7: 73– 81Crossref, Google Scholar

29 Gelber H, Alexander M: An evaluation of an Australian videoconferencing project for child and adolescent telepsychiatry. J Telemed Telecare 1999; 5 ( suppl 1): S21– S23Crossref, Google Scholar

30 Greenberg N, Boydell K, Volpe T: Pediatric telepsychiatry in Ontario: caregiver and service provider perspectives. J Behav Health Serv Res 2006; 33: 105– 111Crossref, Google Scholar

31 Hockey A, Yellowlees P, Murphy S: Evaluation of a pilot second-opinion child telepsychiatry service. J Telemed Telecare 2004; 10 ( suppl 1): 48– 50Crossref, Google Scholar

32 Jackim L: With child M.D.s in short supply, organizations get creative. Behav Healthcare Tomorrow 2004; 13 ( 1): 23– 27Google Scholar

33 Keilman P: Telepsychiatry with child welfare families referred to a family service agency. Telemed J E Health 2005; 11: 98– 101Crossref, Google Scholar

34 Kopel H, Nunn K, Dossetor D: Evaluating satisfaction with a child and adolescent psychological telemedicine outreach service. J Telemed Telecare 2001; 7 ( suppl 2): 35– 40Crossref, Google Scholar

35 Starling J, Rosina R, Nunn K, Dossetor D: Child and adolescent telepsychiatry in New South Wales: moving beyond clinical consultation. Australas Psychiatry 2003; 11 ( suppl): S117– S121Crossref, Google Scholar

36 Yellowless PM, Hilty DM, Marks SL, Neufeld J, Bourgeois JA: A retrospective analysis of a child and adolescent mental health program. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2008; 47: 103– 107Crossref, Google Scholar

37 Haythornthwaite S: Videoconferencing training for those working with as-risk young people in rural areas of Western Australia. J Telemed Telecare 2002; 8 ( suppl 3): 29– 33Google Scholar

38 Mitchell J, Robinson P, Seiboth C, Koszegi B: An evaluation of a network for professional development in child and adolescent mental health in rural and remote communities. J Telemed Telecare 2000; 6: 158– 163Crossref, Google Scholar

39 Alessi N: Child and adolescent telepsychiatry: reliability studies needed. Cyberpsychol Behav 2000; 3: 1009– 1015Crossref, Google Scholar

40 Boydell KM, Greenberg N, Tiziana V: Designing a framework for the evaluation of paediatric telepsychiatry: a participatory approach. J Telemed Telecare 2004; 10: 165– 169Crossref, Google Scholar

41 Pesamaa L, Ebeling H, Kuusimaki M-L, Winbald I, Isohanni M, Moilanen I: Videoconferencing in child and adolescent telepsychiatry: a systematic review of the literature. J Telemed Telecare 2004; 10: 187– 192Crossref, Google Scholar

42 Hilty DM, Luo JS, Morache C, Marcelo DA, Nesbitt TS: Telepsychiatry: an overview for psychiatrists. CNS Drugs 2002; 16: 527– 548Crossref, Google Scholar

43 Hilty DM, Marks SL, Urness D, Yellowless PM, Nesbitt TS: Clinical and educational telepsychiatry applications: a review. Can J Psychiatry 2004; 49: 1– 2Crossref, Google Scholar

44 National Initiative for Telehealth: National Initiative for Telehealth Framework of Guidelines. Ottawa, 2003Google Scholar