An Update on Autism

Abstract

The autism spectrum disorders (ASDs) are relatively common disorders characterized by profound disturbances in social skills. Although the prevalence of ASDs has increased, this increase reflects changes in diagnostic criteria, public awareness, and standards for eligibility for services. The ASDs have a strong genetic basis and are characterized by several neurobiological abnormalities. Various mechanisms have been proposed, but no single factor has emerged as necessary or sufficient to cause ASDs. A thorough diagnostic assessment requires a multidisciplinary evaluation using specialized rating scales and questionnaires. ASDs co-occur with a variety of medical and psychiatric disorders, and the population with these disorders may have difficulty describing what they are experiencing; thus any evaluation should include careful assessment for a range of symptoms. Behavioral and pharmacological interventions are most successful in maximizing adaptive function and ameliorating symptoms but do not treat the core features of the disorders. With better detection and intervention, more children with ASD are becoming self-sufficient adults, and more general psychiatrists are being consulted for a range of different problems. An increasingly important part of caring for children with ASDs is planning for adolescence and adulthood. Inroads are being made in early characterization and diagnosis, and genetic and neurobiological mechanisms are being elucidated. This work is being integrated with the emerging body of social neuroscience research. The autism research field, as a whole, is in a period of great productivity and holds great promise for clarifying etiology and refining intervention in the near future.

Autism and related disorders, referred to as either the pervasive developmental disorders (PDDs) or autism spectrum disorders (ASDs), are a group of conditions characterized by a profound disturbance in socialization skills. The prototypic disorder in this group, autistic disorder, was first described by Leo Kanner as an “inborn disorder of affective contact” or “early infantile autism” (1). He indicated that the disorder was of early onset and probably congenital and was careful to cast his description in a strong developmental context. Although once thought to be a rare disorder, it has become increasingly clear, as we discuss later, that autism is a relatively common problem and has a strong genetic component. It also appears that as a result of better case detection and intervention, more and more children with autism are becoming self-sufficient adults. As a result, more general psychiatrists are now being asked to consult with adolescents and adults with autism who also suffer from a range of other problems.

DIAGNOSIS AND DEFINITION

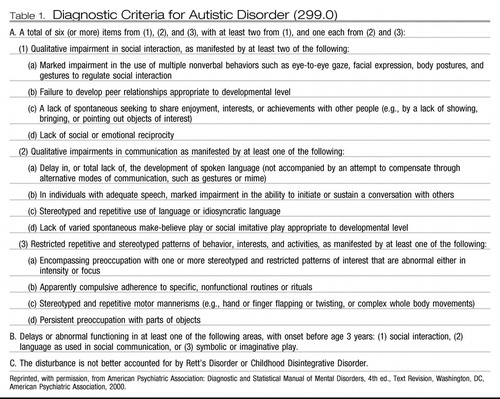

Kanner's original report emphasized two essential features: a lack of social engagement (autism) and an insistence on sameness or resistance to change. The latter category also included many of the unusual stereotyped motor mannerisms that Kanner believed served the function of maintaining sameness. Kanner's use of Bleuler's word “autism” to describe social detachment (rather than self-centered thinking) was evocative but also led to the confusion of autism with schizophrenia for several decades. The work of Kolvin (2) and Rutter (3) made it clear that autism was not a form of schizophrenia, and that these conditions could be distinguished by both phenomenology and epidemiology. The increased interest in autism and the body of work on its validity led to inclusion of the disorder in the landmark DSM-III. Over time the definition of the condition has been refined and the current version was developed on the basis of an extensive field trial (4). Criteria for the condition are listed in Table 1. Deficits in communication and play, as well as restricted interests and behaviors are required, but the social aspect is more heavily emphasized. The available data suggest that this definition has worked reasonably well, and it is in widespread use around the world.

|

Table 1. Diagnostic Criteria for Autistic Disorder (299.0)

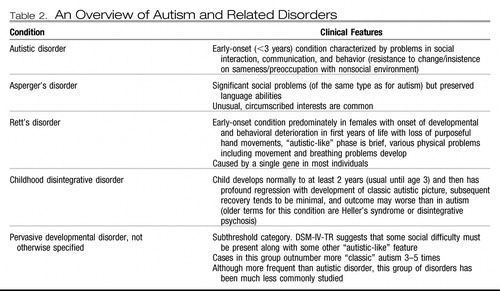

Other conditions included with autism in the PDD or ASD class include Asperger's disorder, a condition in which social difficulties exist, but language skills are mostly preserved (5), Rett's disorder, a degenerative condition now known to be frequently associated with a specific genetic defect (6), and childhood disintegrative disorder, a very rare condition first described in 1908 (then called Heller's syndrome) in which children develop normally for 3 or 4 years before having a profound regression and development of what otherwise appears to be a classic autistic symptom picture (7). In addition, a subthreshold category, pervasive developmental disorder, not otherwise specified, is included; this condition has its own history antedating DSM-III and is probably three to five times more common than autism if the latter is strictly defined (8). Features of these conditions are summarized in Table 2.

|

Table 2.

The current approach to diagnosis works well for preschool and older children but may be more problematic in its application to very young children. Frequently children younger than age 3 have social and communication troubles but have not exhibited obviously repetitive, nonfunctional patterns of behavior, making diagnostic categorization more difficult (9, 10). For older individuals, particularly those with higher levels of function, a lack of historical information can complicate diagnosis. Various rating scales and checklists have been developed which, to some degree, address this problem (11).

EPIDEMIOLOGY AND DEMOGRAPHICS

In his review of the many epidemiological studies of autism, Fombonne (12) noted a broad range of estimates of prevalence with a median rate of about 1.1 cases per 1,000 individuals. Although a review of the available data does suggest a recent increase in cases, it is also the case that diagnostic criteria have changed and public awareness has increased. In addition, there is a tendency in the press to equate autism (strictly defined) with “autism spectrum” (broadly defined, including pervasive developmental disorder, not otherwise specified). A range of other factors, including use of the label “autism” to obtain services, complicates the interpretation of the apparent secular change in prevalence.

A male predominance is reported consistently: typically three to five boys for every girl. However, girls with autism are more likely to have associated intellectual disability. Although the established criteria for autism appear to work well around the world, the ways in which different cultures respond to the needs of children with autism vary. Relatively little work has been done on the cultural or ethnic aspects of autism although some work suggests a tendency for underdiagnosis of autism in poor and disadvantaged populations (13).

ETIOLOGY AND PATHOGENESIS

An array of factors underlie the pathogenesis of ASD. Inheritance patterns clearly mark a significant genetic component: There are greatly increased rates of ASD in the relatives of people with the disorder: The siblings of children with autism have between a 5% and 10% chance of having autism themselves (14, 15): When a monozygotic twin has an ASD, the sibling has a 40%–92% chance of also having the diagnosis, whereas monozygotic twins share the diagnosis in only 5%–10% of cases (16). There has been recent progress in the identification of candidate genes, including CTNAP2, DISC1, and RELN (17), as a result of advances in the field of genetics, including the sequencing of the human genome, as well as the collaborations of many genetics laboratories (18). The identification of multiple candidate genes coupled with the failure to isolate a single causal gene emphasizes the fact that ASD most likely reflects a complex interaction between multiple genes (19).

Abnormal brain activity is evident on electroencephalographic (EEG) studies of many subjects with ASD (20, 23), and many have seizure disorders (22, 23). In addition, young children with ASD generally exhibit a period of abnormal brain development, marked in part by larger than average head circumference (24, 25). Schultz et al. (26) have identified differences in brain processing of social information, e.g., of faces, which may account for major aspects of the social difficulty observed. A number of other important neurobiological findings have also emerged including higher rates of EEG anomalies, increased brain volume, decreased size of the corpus callosum, and abnormal processing of face stimuli in the inferotemporal cortex (21, 27–31).

Various cognitive theories of autism have been proposed. Each of these accounts for the various behaviors seen in autism on the basis of a psychological mechanism. Clearly they are important in the search for the causes of autism but also can inform clinical care by suggesting therapeutic approaches. A significant challenge has been to fit these theories to the emerging evidence from neuroimaging studies that ASDs are characterized by widespread neuroanatomical and neurophysiological irregularities (see above).

The “theory of mind” hypothesis suggests that autism is caused by an inability to attribute mental states to others (32). This leads to a social landscape devoid of intention, belief, desire, and, by extension, impairments in communication and social contact. The “weak central coherence” theory suggests that details of the environment are processed at the cost of higher-level meaning, leading to a fragmented experience of the world (33). Another account implicates deficits in “executive functioning” that impair goal-directed and future-oriented behaviors (34). The “enactive mind” hypothesis proposes that reduced relevance of social stimuli and the derailment of early social cognitive processes result in the oversalience of irrelevant aspects of the environment (35). This notion is consistent with recent research using eye tracking methods, which has documented the difficulties individuals with autism have in following social situations tending, for example, to focus on mouths rather than on eyes when they watch social scenes (Figure 1). As research tools become more refined and information about autism accumulates, theoretical explanations will become easier to test.

Figure 1. Visual focus of an autistic man (black line) and a normal comparison subject (white line) shown a film clip of a conversation.

Leo Kanner, who described the first patients with autism in the United States, theorized that autism may result from a failure of the infant-parent bond. This theory was championed by Bruno Bettleheim and known colloquially as the “refrigerator mother” hypothesis. Although there was no evidence for it at the time and it has been conclusively refuted, the devastating effects that this theory had on many families provides a cautionary lesson for today.

Wakefield et al. (36) suggested an association between measles vaccine and autism, and as a result many parents have been focused on immunizations. The suggestion of Wakefield et al. that measles vaccine caused autism has not been supported, but the emphasis has shifted to the mercury-based preservative thimerosal used as a preservative at the time in many vaccines (37). Thimerosal was removed from all but the flu vaccine 7 years ago, without any subsequent decrease in the incidence of autism (38), but the impact on the lay press and the public has been tremendous. It is becoming increasingly apparent that a single environmental factor is neither necessary nor sufficient to cause autism, but rather that some complex and varying interplay between multiple genes and multiple environmental factors is to blame.

EVALUATION AND TREATMENT PLANNING

A “gold standard” evaluation of a child suspected of having an ASD includes a comprehensive developmental and medical history, an assessment of cognitive and adaptive function, and input from several different specialties that may include psychology, psychiatry, speech and language pathology, neurology, developmental pediatrics, social work, and occupational and physical therapy. Such an extensive workup reflects the complexity of the ASDs, in particular emphasizing the fact that they affect multiple functional domains. As a result, the focus of any evaluation should be on characterizing the individual's profile of abilities, rather than in trying to apply a diagnostic label. On the other hand, it is also important to recognize that diagnostic labels are often necessary to ensure appropriate provision of services.

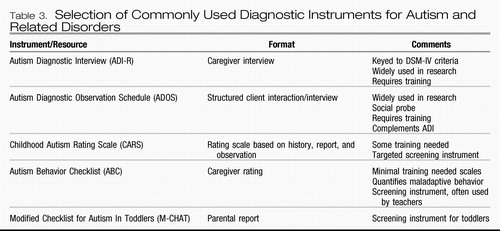

A variety of components are fundamental to an initial evaluation including the Autism Diagnostic Observation Scale (ADOS), the Autism Diagnostic Interview (ADI), and a parent interview (39). In many cases, however, a clinical interview designed to establish whether a child meets DSM criteria is all that is available. Important details will almost always be missed using this approach. Furthermore, many of the instruments available today are standardized, helping to maximize the quality of communication between practitioners. When these instruments are unavailable, practitioners are advised to refer families to a group specialized in autism spectrum disorders for an initial evaluation whenever possible.

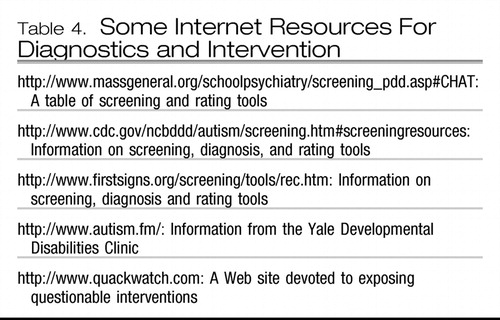

The ADOS and the ADI are the best diagnostic instruments available, providing excellent information about the strengths and weaknesses of an individual (Tables 3 and 4). Both, however, require specialized training and take a significant amount of time to administer, and they do not distinguish between the various ASDs, a task that is most effectively completed by a clinician with experience in this area.

|

Table 3. Selection of Commonly Used Diagnostic Instruments for Autism and Related Disorders

|

Table 4. Some Internet Resources For Diagnostics and Intervention

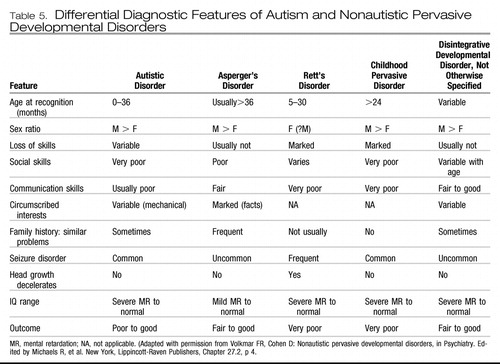

During an evaluation the ASDs must be distinguished not only from one another but also from a host of other developmental disorders including selective mutism, child-onset schizophrenia, and various degenerative central nervous system disorders. In general, Rett's syndrome and childhood disintegrative disorder (both of which are degenerative central nervous system disorders) are clearly distinguished by their natural history. Distinguishing autistic disorder, pervasive developmental disorders, not otherwise specified, and Asperger's disorder can be challenging but is particularly important for planning intervention. Table 5 lists features that distinguish the ASDs.

|

Table 5. Differential Diagnostic Features of Autism and Nonautistic Pervasive Developmental Disorders

The ASDs are a heterogeneous group of disorders and frequently co-occur with other disorders, making untangling symptoms due to autism from those caused by other conditions difficult. Some of the behaviors that characterize the ASDs, including repetitive “self stimulatory behavior (stimming), for example, hand flipping,” self-injurious behavior, and aggression, also frequently occur in the population with severe intellectual disabilities. In general, a social deficit disproportionate to the intellectual disability marks an ASD. The younger population of children with ASD frequently experience difficulties with attention and often come to medical attention first because of this. In adolescents, symptoms of anxiety and depression are frequent, often due to social difficulties. Obsessive and compulsive behaviors are challenging to distinguish from the routines, rituals, and self-stimulatory behavior of children with ASD. Children who have suffered neglect may also exhibit social impairments and in extreme cases may have autistic-like behaviors.

Fombonne (12) estimates that medical comorbidities occur in approximately 5% of children with ASD. Seizure disorders occur in between 20 and 40% of the population with ASD and have a bimodal distribution of onset in infancy and adolescence (22, 23). Tuberous sclerosis, a rare genetic disorder in which benign tumors develop in multiple organ systems, is associated both with autism and seizure disorders. Between 17% and 61% of children with tuberous sclerosis meet the criteria for an ASD (20) and, among the population with autism, the incidence of tuberous sclerosis is 1% (40). Whether the autism apparent in tuberous sclerosis results from the effects of the tumors or of epilepsy or directly from a genetic defect or from some combination of these is unclear.

Tuberous sclerosis promises to provide an important window into the pathophysiology of ASD. Between 2% and 4% of children with autism have fragile X syndrome (41), another condition with a genetic basis and the most common cause of inherited intellectual disability. Furthermore, the majority of children with fragile X syndrome exhibit autistic behaviors, in particular social impairments and stereotypies (42). Gastrointestinal disturbances are a controversial topic in the ASD literature, and the focus of various therapies that have not been empirically validated. A recent review suggests that current evidence does not support this association (43).

On the whole, an extensive genetic workup yields little, unless evidence of a syndrome is present. Some basic tests can be informative, in particular when an intellectual disability is present (44). A hearing test is important if none has been done before. If evidence that a neurological problem is present, such as motor impairments or seizures, specialized consultation is important, and brain imaging and an EEG may be indicated (45).

TREATMENT

There is no cure for ASD, and no current therapy adequately addresses the core features of these disorders. Behavioral interventions are best targeted for improving adaptive skills, and psychopharmacology can play a role in ameliorating symptoms.

The best behavioral interventions are targeted to an individual's profile of abilities. In a high-functioning child without intellectual disability, for example, an emphasis on social skills training may be most beneficial. On the other hand, a very disabled child with aggressive, self-injurious behaviors may benefit more from intensive, highly structured behavioral management. The most effective behavioral approaches are based on the principles of applied behavioral analysis, a family of “conceptually consistent techniques” with the common elements of “specific curriculum content, highly supportive teaching environments and generalization strategies, predictable routine, functional approach to problem behaviors, planned transition, and family involvement” (46). The National Research Council (2001) identified early intervention, structure, frequency, and intensity as the factors most important to successful intervention. For more able adults, comorbid depression and anxiety problems are frequent, and supportive psychotherapy and counseling may provide important benefits. Psychotherapy should be primarily focused on fostering adaptive skills and independence, providing social supports and feedback, and helping individuals deal with problematic situations.

Drugs from several pharmacological classes may be effective for treating some of the symptoms of autism. Many people with ASD appear to experience more dramatic side effects to pharmacological agents in general. Furthermore, communication difficulties may obscure these side effects. Therefore, medication trials should include slower than typical titrations and more intensive monitoring for side effects.

The atypical antipsychotics are currently used to treat aggressive and disruptive behaviors. The effectiveness of risperidone for the treatment of aggression, tantrums, and self-injury was recently demonstrated by a large multisite trial (47), paving the way for the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to approve the drug for use in the population between ages 5 and 16 with ASD. During this trial some decrease was noted in repetitive behavior and hyperactivity, and modest improvements were seen in some adaptive skills. The other atypical antipsychotic drugs, although not currently approved by the FDA for use in this population, may be effective for the same purposes and have different side effect profiles and so may be useful when risperidone is not tolerated. However, other antipsychotic drugs have not been studied with the same rigor as risperidone has. All antipsychotic medications carry the risk of significant and dangerous side effects and thus should be used carefully and with a timeline and a clear target behavior in mind.

The selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) can be useful for treating repetitive behaviors as well as depression and anxiety although there is some potential for activation (47). Similarly, the antiepileptic drugs are regularly used in the ASD population for seizure control and in some cases are used to dampen mood lability (48). A large trial of methylphenidate, a stimulant, demonstrated that the drug was effective for treatment of disruptive and impulsive behaviors in this population but also showed that these individuals are more vulnerable to side effects (49). A variety of other drugs, including naltrexone, secretin, and antifungal drugs have failed to demonstrate efficacy.

A host of alternative or complementary treatments have been proposed. Jacobson et al. (50) have written a comprehensive review on this topic. For example, the belief that heavy metals cause autism has led to the use of chelating agents as a treatment for autism. Not only is there no evidence that this approach works but it can also be dangerous (51). Steroids have also been used to ill effect on the basis of the unproven hypothesis that autism results from an inflammatory response. In a few instances, e.g., with the gut hormone secretin, careful double-blind studies have been performed and failed to show improvement over placebo (52). In most instances alternative or complementary treatments pose little risk to the child although, at times, there can be a risk related to stopping a proven treatment and expending considerable financial and personal resources; occasionally, there is some actual risk to the child.

There is no cure for autism, but the social, adaptive, and communicative skills of children with autism improve with treatment. Although some individuals continue to need considerable support as adults, many are now able to live independently or semi-independently (53). Factors predicting good outcome include preservation of nonverbal cognitive skills, the presence of communicative speech by approximately age 5, and social and adaptive function (53). It is possible that earlier diagnosis and intervention have improved outcome (10), although changing diagnostic practices may confuse this issue (53). Even when self-sufficiency is attained, a significant social disability remains in most individuals. Therefore, an extremely important component of caring for a child with an ASD is to encourage and contribute to a plan for adolescence and adulthood. It is important for psychiatrists working with adults to be aware of the possibility of autism or a related disorder in their work, particularly with individuals with social difficulties.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS

There have been many advances in the past decade. Advances in diagnosis and treatment have, in turn, facilitated work on genetics and neurobiological processes. Significant advances have been made in understanding aspects of pathophysiology and the field is now poised, as genes are identified, to relate genetic mechanisms to brain expression and clinical features. The increased support of both governmental and nongovernmental groups has been significant in this effort.

There are several areas of active work in the field at present. Studies focused on autism as it first appears in life, i.e., in infants, are underway at several centers. This work, using prospective designs (e.g., of siblings) is important as it may help us understand the first manifestations of autism. Such information may help us disentangle which processes are most important to study and may also hold promise for early screening (10). The move toward performance-based screening tools for infants and toddlers at risk is an important development and one that may facilitate early intervention and better outcome.

Potential mechanisms and genes involved in autism are being actively explored in neurobiological and genetic studies. The integration of this research with the emerging body of social neuroscience research will be critical in helping us understand exactly what is inherited in autism. Although treatment studies remain some of the most difficult to conduct, more such studies have appeared over the past decade. The model provided by the Research Unit Pediatric Psychopharmacology (RUPP) is an excellent example of the type of cross-site study needed for treatments of all kinds.

As a result of better diagnosis and treatment and the better identification of more cognitively able individuals with autism in DSM-IV, it is increasingly likely that general psychiatrists will encounter adults with autism-related disorders in their practice. Increasing numbers of these individuals are entering the workforce, attending college, and assuming active roles in their communities. This development is to be welcomed but also makes it important that the psychiatric needs of this population be met.

1 Kanner L: Autistic disturbances of affective contact. Nerv Child 1943; 2: 217– 250Google Scholar

2 Kolvin I: Studies in the childhood psychoses. I. Diagnostic criteria and classification. Br J Psychiatry 1971; 118: 381– 384Crossref, Google Scholar

3 Rutter M: Childhood schizophrenia reconsidered. J. Autism Child Schizophr 1972; 2: 315– 337Crossref, Google Scholar

4 Volkmar FR, Klin A, Siegel B, Szatmari P, Lord C, Campbell M, Freeman BJ, Cicchetti DV, Rutter M, Kline W: Field trial for autistic disorder in DSM-IV. Am J Psychiatry 1994; 151: 1361– 1367Crossref, Google Scholar

5 Klin A, Pauls D, Schultz R, Volkmar F: Three diagnostic approaches to Asperger syndrome: implications for research. J Autism Dev Disord 2005; 35: 221– 234Crossref, Google Scholar

6 Van Acker R: Rett syndrome: a review of current knowledge. J Autism Dev Disord 1991; 21: 381– 406Crossref, Google Scholar

7 Volkmar FR, Koenig K, State M: Childhood disintegrative disorder, in Handbook of Autism and Pervasive Developmental Disorders, 3rd ed. Edited by Volkmar FR, Klin A, Marans W, Cohen DJ. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2005, pp 70– 87Google Scholar

8 Towbin KE: Pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified, in Handbook of Autism and Pervasive Developmental Disorders, 3rd ed. Edited by Volkmar FR, Klin A, Marans W, Cohen DJ. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2005, pp 165– 200Google Scholar

9 Lord C, Pickles A: Language level and nonverbal social-communicative behaviors in autistic and language-delayed children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1996; 35: 1542– 1550Crossref, Google Scholar

10 Chawarska K, Klin A, Volkmar F: Autism Spectrum Disorders in Infants and Toddlers: Diagnosis, Assessment, and Treatment, 1st ed. New York, Guilford, 2008Google Scholar

11 Lord C, Wagner A, Rogers S, Szatmari P, Aman M, Charman T, Dawson G, Durand VM, Grossman L, Guthrie D, Harris S, Kasari C, Marcus L, Murphy S, Odom S, Pickles A, Scahill L, Shaw E, Siegel B, Sigman M, Stone W, Smith T, Yoder P: Challenges in evaluating psychosocial interventions for autistic spectrum disorders. J Autism Dev Disord 2005; 35: 695– 708; discussion 709–711Crossref, Google Scholar

12 Fombonne E: Epidemiology of autistic disorder and other pervasive developmental disorders. J Clin Psychiatry 2005; 66 ( suppl 10): 3– 8Google Scholar

13 Mandell DS, Ittenbach RF, Levy SE, Pinto-Martin JA: Disparities in diagnoses received prior to a diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder. J Autism Dev Disord 2007; 37: 1795– 1802Crossref, Google Scholar

14 Jones MB, Szatmari P: Stoppage rules and genetic studies of autism. J Autism Dev Disord 1988; 18: 31– 40Crossref, Google Scholar

15 Ritvo ER, Jorde LB, Mason-Brothers A, Freeman BJ, Pingree C, Jones MB, McMahon WM, Petersen PB, Jenson WR, Mo A: The UCLA-University of Utah epidemiologic survey of autism: recurrence risk estimates and genetic counseling. Am J Psychiatry 1989; 146: 1032– 1036Crossref, Google Scholar

16 Bailey A, Le Couteur A, Gottesman I, Bolton P, Simonoff E, Yuzda E, Rutter M: Autism as a strongly genetic disorder: evidence from a British twin study. Psychol Med 1995; 25: 63– 77Crossref, Google Scholar

17 Abrahams BS, Geschwind DH: Advances in autism genetics: on the threshold of a new neurobiology. Nat Rev Genet 2008; 9: 341– 355Crossref, Google Scholar

18 Gupta AR, State MW: Recent advances in the genetics of autism. Biol Psychiatry 2007; 61: 429– 437Crossref, Google Scholar

19 Risch N, Spiker D, Lotspeich L, Nouri N, Hinds D, Hallmayer J, Kalaydjieva L, McCague P, Dimiceli S, Pitts T, Nguyen L, Yang J, Harper C, Thorpe D, Vermeer S, Young H, Hebert J, Lin A, Ferguson J, Chiotti C, Wiese-Slater S, Rogers T, Salmon B, Nicholas P, Petersen PB, Pingree C, McMahon W, Wong DL, Cavalli-Sforza LL, Kraemer HC, Myers RM: A genomic screen of autism: evidence for a multilocus etiology. Am J Hum Genet 1999; 65: 493– 507Crossref, Google Scholar

20 Chez MG, Chang M, Krasne V, Coughlan C, Kominsky M, Schwartz A: Frequency of epileptiform EEG abnormalities in a sequential screening of autistic patients with no known clinical epilepsy from 1996 to 2005. Epilepsy Behav 2006; 8: 267– 271Crossref, Google Scholar

21 Minshew NJ: Brief report: brain mechanisms in autism: functional and structural abnormalities. J Autism Dev Disord 1996; 26: 205– 209Crossref, Google Scholar

22 Danielsson S, Gillberg IC, Billstedt E, Gillberg C, Olsson I: Epilepsy in young adults with autism: A prospective population-based follow-up study of 120 individuals diagnosed in childhood. Epilepsia 2005; 46: 918– 923Crossref, Google Scholar

23 Volkmar FR, Nelson DS: Seizure disorders in autism. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1990; 29: 127– 129Crossref, Google Scholar

24 Courchesne E, Carper R, Akshoomoff N: Evidence of brain overgrowth in the first year of life in autism. JAMA 2003; 290: 337– 344Crossref, Google Scholar

25 Hazlett HC, Poe M, Gerig G, Smith RG, Provenzale J, Ross A, Given J, Piven J: Magnetic resonance imaging and head circumference study of brain size in autism: birth through age 2 years. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2005; 62: 1366– 1376Crossref, Google Scholar

26 Schultz RT: Developmental deficits in social perception in autism: the role of the amygdala and fusiform face area. Int J Dev Neurosci 2005; 23: 125– 141Crossref, Google Scholar

27 Casanova MF, Buxhoeveden DP, Switala AE, Roy E: Minicolumnar pathology in autism. Neurology 2002; 58: 428– 432Crossref, Google Scholar

28 DiCicco-Bloom E, Lord C, Zwaigenbaum L, Courchesne E, Dager SR, Schmitz C, Schultz RT, Crawley J, Young LJ: The developmental neurobiology of autism spectrum disorder. J Neurosci 2006; 26: 6897– 6906Crossref, Google Scholar

29 Pardo CA, Eberhart CG: The neurobiology of autism. Brain Pathol 2007; 17: 434– 447Crossref, Google Scholar

30 Dawson G, Webb SJ, McPartland J: Understanding the nature of face processing impairment in autism: insights from behavioral and electrophysiological studies. Dev Neuropsychol 2005; 27: 403– 424Crossref, Google Scholar

31 Williams JHG, Whiten A, Suddendorf T, Perrett DI: Imitation, mirror neurons and autism. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2001; 25: 287– 295Crossref, Google Scholar

32 Baron-Cohen S: Mindblindness: An Essay on Autism and Theory of Mind. Cambridge, Mass, MIT Press, 1995Google Scholar

33 Frith U: Autism: Explaining the Enigma. Oxford, England: Blackwell Scientific, 1989Google Scholar

34 Ozonoff S: Executive functions in autism, in Learning and Cognition in Autism, 3rd ed. Edited by Schopler E, Mesibov GB. New York: Plenum Press, 1995, pp 199– 219Google Scholar

35 Klin A, Jones W, Schultz R, Volkmar F: The enactive mind, or from actions to cognition: lessons from autism. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 2003; 358: 345– 360Crossref, Google Scholar

36 Wakefield AJ, Murch SH, Anthony A, Linnell J, Casson DM, Malik M, Berelowitz M, Dhillon AP, Thomson MA, Harvey P, Valentine A, Davies SE, Walker-Smith JA: Ileal-lymphoid-nodular hyperplasia, non-specific colitis, and pervasive developmental disorder in children. Lancet 1998; 351: 637– 641Crossref, Google Scholar

37 Bernard S, Enayati A, Redwood L, Roger H, Binstock T: Autism: a novel form of mercury poisoning. Med Hypotheses 2001; 56: 462– 471Crossref, Google Scholar

38 Schechter R, Grether JK: Continuing increases in autism reported to California's developmental services system: mercury in retrograde. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2008; 65: 19– 24Crossref, Google Scholar

39 McEachin JJ, Smith T, Lovaas OI: Long-term outcome for children with autism who received early intensive behavioral treatment. Am J Ment Retard 1993; 97: 359– 372Google Scholar

40 Wong V: Study of the relationship between tuberous sclerosis complex and autistic disorder. J Child Neurol 2006; 21: 199– 204Google Scholar

41 Filipek PA: Medical aspects of autism, in Handbook of Autism and Pervasive Developmental Disorders, 3rd ed. Edited by Volkmar FR, Klin A, Marans W, Cohen DJ. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, pp 534– 578Google Scholar

42 Feinstein C, Singh S: Social phenotypes in neurogenetic syndromes. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin North Am 2007; 16: 631– 647Crossref, Google Scholar

43 Erickson CA, Stigler KA, Corkins MR, Posey DJ, Fitzgerald JF, McDougle CJ: Gastrointestinal factors in autistic disorder: a critical review. J Autism Dev Disord 2005; 35: 713– 727Crossref, Google Scholar

44 Cohen D, Pichard N, Tordjman S, Baumann C, Burglen L, Excoffier E, Lazar G, Mazet P, Pinquier C, Verloes A, Héron D: Specific genetic disorders and autism: clinical contribution towards their identification. J Autism Dev Disord 2005; 35: 103– 116Crossref, Google Scholar

45 Minshew NJ: What is currently known about the neurobiology of autism and if the valuable resource of family time should be invested in these studies. J Autism Dev Disord 2004; 34: 737– 738Crossref, Google Scholar

46 Anderson SR, Romanczyk RG: Early intervention for young children with autism: continuum-based behavioral models. Res Pract Persons Severe Disabil 1999; 24: 162– 173Crossref, Google Scholar

47 McCracken JT, McGough J, Shah B, Cronin P, Hong D, Aman MG, Arnold LE, Lindsay R, Nash P, Hollway J, McDougle CJ, Posey D, Swiezy N, Kohn A, Scahill L, Martin A, Koenig K, Volkmar F, Carroll D, Lancor A, Tierney E, Ghuman J, Gonzalez NM, Grados M, Vitiello B, Ritz L, Davies M, Robinson J, McMahon D; Research Units on Pediatric Psychopharmacology Autism Network: Risperidone in children with autism and serious behavioral problems. N Engl J Med 2002; 347: 314– 321Crossref, Google Scholar

48 Scahill L, Martin A: Psychopharmacology, in Handbook of Autism and Pervasive Developmental Disorders, 3rd ed. Edited by Volkmar FR, Klin A, Marans W, Cohen DJ. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, pp 1102– 1122Google Scholar

49 Research Units on Pediatric Psychopharmacology Autism Network: Randomized, controlled, crossover trial of methylphenidate in pervasive developmental disorders with hyperactivity. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2005; 62: 1266– 1274Crossref, Google Scholar

50 Jacobson JW, Foxx RM, Mulick JA: Controversial Therapies for Developmental Disabilities: Fad, Fashion and Science in Professional Practice. Mahwah, NJ, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 2005Google Scholar

51 Brown MJ, Willis T, Omalu B, Leiker R: Deaths resulting from hypocalcemia after administration of edetate disodium: 2003–2005. Pediatrics 2006; 118: e534– e536Crossref, Google Scholar

52 Unis AS, Munson JA, Rogers SJ, Goldson E, Osterling J, Gabriels R, Abbott RD, Dawson G: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of porcine versus synthetic secretin for reducing symptoms of autism. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2002; 41: 1315– 1321Crossref, Google Scholar

53 Howlin P: Outcomes in autism spectrum disorders, in Handbook of Autism and Pervasive Developmental Disorders, 3rd ed. Edited by Volkmer FR, Klin A, Marans W, Cohen DJ. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, pp 201– 222Google Scholar