Early-Onset Bipolar Disorder

Abstract

Despite dramatic increases in the rate at which bipolar disorder is being diagnosed in children and adolescents, there remain several outstanding questions regarding definitional issues, valid assessment procedures, effective treatment approaches, and the degree of continuity between early-onset bipolar disorder phenotypes and adult forms of the illness. In the present article, the authors provide a historical context for the current interest in early-onset bipolar spectrum conditions, followed by a discussion of phenomenology, definitional issues, prevalence rates, common comorbidities, differential diagnosis, course of illness, assessment, and treatment. The value of maintaining a multidisciplinary approach is emphasized, as well as the importance of going beyond standardized diagnostic criteria to understand the current and developmental contexts in which behaviors are being expressed.

Accompanying the striking increase in the frequency with which pediatric bipolar disorder is being diagnosed in the United States (1, 2), there has been significant controversy and confusion surrounding the definition, assessment, and treatment of this condition. A recent research forum on risk and protective factors in the development of pediatric bipolar disorder identified lack of consensus regarding definition and assessment practices as the primary barrier to progress in our understanding of etiological and maintenance factors in the development of pediatric bipolar spectrum conditions (3). Although there is general agreement that bipolar disorder can occur in children and adolescents, there remain several unanswered questions regarding the frequency with which it manifests, the best ways to measure and define it, and the degree of continuity between early-onset bipolar disorder phenotypes and adult forms of the illness (4).

HISTORY

Interest in identifying early-onset forms of manic depression can be traced back more than a century (see reference 5 for a review). Efforts increased following publication of Kraepelin's monograph on manic-depressive insanity (6), as child psychiatrists began to examine their patients, looking for similar presentations in youth. Subsequent case studies suggested that manic depression in children was rare and that when it did occur it was highly familial and most frequently was seen after onset of adolescence (5). At the same time, there was some suggestion that mania was being overlooked in younger children, because of its overlap with other childhood diagnoses and normative childhood behavior (7). Efforts to characterize early-onset mania were temporarily stalled in the 1960s after the publication of an influential article by Anthony and Scott (8), in which the authors reviewed the existing literature in this area and determined that the vast majority of published cases had been misdiagnosed.

Evidence of the efficacy of lithium for treating adults with manic depression led to interest in identifying lithium-responsive clinical profiles in children. Early studies suggested that lithium response was most promising in early-onset presentations resembling classic manic depression, whereas there was no support for use of lithium in treating children with broader behavioral dysregulation (9). At that time, there were several attempts to establish standard criteria for describing early-onset mania. Weinberg and Brumback (10) adapted the Feighner criteria for use with children, whereas Davis (11) introduced a broader definition, which he termed “manic-depressive variant syndrome of childhood.” The latter framework characterized children between 6 and 16 years old exhibiting heightened reactivity to seemingly minor events, hyperactivity, and disruptions in interpersonal relationships, frequently with a family history of manic depression.

By the 1980s, there was growing acceptance of the diagnosis of manic depression, or bipolar disorder as it was now called, in youth. Accompanying research efforts initially focused on describing the phenomenology of pediatric bipolar disorder and establishing standard assessment techniques. In more recent years, there has been a surge of genetic and high-risk studies, as well as investigations of neurobiological, behavioral, and physiological markers. However, there continues to be disagreement regarding the definition and application of specific criteria for bipolar disorder in children, thus significantly challenging these efforts.

DEFINITION

Although there is great diversity in the ways in which bipolar disorder manifests at any age, there are certain commonalities that have been identified in adult patients and operationalized within our current diagnostic system. It has long been recognized that adults with bipolar disorder exhibit an episodic pattern to their symptomatology. DSM-IV-TR defines a mood episode as a “distinct period” during which a person exhibits specific co-occurring symptoms. Mania is described as an “abnormally and persistently elevated, expansive, or irritable mood” that is accompanied by at least three additional symptoms (four if mood is irritable) including inflated self-esteem or grandiosity, decreased need for sleep, pressured speech, flight of ideas, distractibility, increased involvement in goal-directed activities or psychomotor agitation, and excessive involvement in pleasurable activities with a high potential for painful consequences. To meet the full criteria for mania, symptoms must last at least 1 week, or 4 days for hypomania. Episodes of depression last at least 2 weeks. Although functional impairment and subsyndromal mood symptoms may persist between episodes (12), episodes represent a clear departure from baseline functioning.

The DSM-IV-TR distinguishes among four bipolar phenotypes.

Bipolar I disorder is the most severe, requiring the presence of at least one manic or mixed episode. Depressive episodes are not required for a diagnosis of bipolar I disorder but are usually present.

Bipolar II disorder is defined by a history of one or more major depressive episodes and at least one hypomanic episode.

Cyclothymic disorder involves chronic and variable symptoms of hypomania and depression and is believed to represent a “temperamental predisposition” to more severe forms of bipolar disorder.

Bipolar disorder not otherwise specified is diagnosed when mood symptoms are insufficient in number and/or duration to meet full criteria. The DSM-IV-TR also provides a series of specifiers for making a diagnosis of bipolar disorder, which characterize the illness in terms of severity and chronicity, seasonal patterns, and rapid cycling.

Symptom patterns in youth with bipolar disorder often do not resemble the episodic nature of bipolar disorder in adults as it has been classically described (13). According to McClellan et al. (14), the most common presentation among youth with bipolar disorder in community settings is characterized by “outbursts of mood lability, irritability, reckless behavior, and aggression.” Shifts in mood state are short-lived (15), and irritability, rather than euphoria, tends to be the predominant and most impairing mood state (16).

Definitional Framework for Diagnosis in Children and Adolescents.

The definitional framework used to diagnose bipolar disorder in children and adolescents varies across research sites. Leibenluft et al. (17) distinguished between narrow phenotype bipolar disorder and a broad bipolar phenotype, which they termed severe mood dysregulation. The former calls for direct application of DSM-IV-TR criteria without modification, including the presence of clear manic/hypomanic episodes characterized by euphoric mood and/or grandiosity. Severe mood dysregulation describes children exhibiting chronic irritability with extreme reactivity to negative stimuli, and symptoms of hyperarousal (18). Geller et al. (19) have developed an alternative framework for describing children with bipolar disorder, which they term Prepubertal and Early Adolescent Onset Bipolar Disorder (PEA-BD). This definition requires that a child exhibit two of three cardinal symptoms of mania (euphoria, grandiosity, and/or irritability), but with reinterpretations of euphoria and grandiosity to take into account the ways in which developmental stage may affect symptom expression. A third early-onset bipolar phenotype, used by Biederman et al. (20), characterizes children who manifest severe, explosive irritability and other symptoms of mania, with or without accompanying grandiosity and euphoric mood.

Even where there is agreement regarding definitional parameters, there may be various ways in which the criteria are applied or interpreted. In a study comparing diagnostic practices regarding pediatric mania in the United Kingdom and the United States, Dubicka et al. (21) enlisted 73 psychiatrists from England and 85 psychiatrists in the United States to formulate provisional Axis I diagnoses in five case vignettes, each describing children with “possible bipolar disorder.” Only one case was considered to be a “classic” case of mania in an adolescent, whereas four were chosen to capture the complexities of diagnosing bipolar disorder in children. Findings showed that U.S. psychiatrists were significantly more likely to diagnose mania in children than were U.K. psychiatrists, whereas psychiatrists in the United Kingdom were more likely to see these children as suffering from pervasive developmental disorders and adjustment disorders. The authors concluded that “results illustrate the current confusion that exists surrounding the diagnosis of prepubertal mania, where similar symptoms may be interpreted to have different diagnostic meanings.”

Definition of an episode.

Perhaps the issue that has caused the most confusion is determining what constitutes an episode among youth with bipolar illness. Geller et al. (22) proposed a definitional framework that takes into account the chronic and rapidly shifting mood variability commonly seen in children with the diagnosis of bipolar disorder. These authors encouraged the use of the term “episode” to describe the length of time that an individual has met the criteria for mania/hypomania or depression and the term “cycle” to refer to shifts in mood that occur throughout the day for every day of the episode. Studies in which this framework has been used have shown that between 78 and 99% of children with bipolar disorder experience daily cycling (22), whereas mean episode duration ranged from 1 to 4 years.

Efforts have been made to adapt adult definitions of the cardinal symptoms of mania for children and adolescents, taking into account developmental differences (23). However, these modifications are difficult to interpret, given the lack of data regarding normative patterns of elated mood and inflated self-esteem in young people and developmental and contextual factors that may moderate the long-term significance of these characteristics. Moreover, it is not clear to what degree atypical levels of silliness and bravado may also be seen in children with other forms of psychopathology such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and pervasive developmental disorders (4). The current American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP) Practice Parameters encourage extreme caution in applying adult criteria for children of preschool age and younger, given that the validity of the diagnosis in such young children has not yet been established and there is an absence of “developmentally valid” assessment methods for evaluating manic symptoms in this age group (14).

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Prevalence rates of bipolar spectrum conditions vary, depending on stage of life and the definitions and methods used to make the diagnosis. Epidemiological samples of prepubertal mania have shown no cases of strictly defined bipolar I disorder (24), whereas rates of severe mood dysregulation are estimated to be 3.3% (25). Rates of bipolar I disorder increase in adolescence with estimates ranging from 0.06% (26) to 0.1% (27) and are closer to 1% in adult community samples (13, 28). Prevalence of bipolar II disorder and cyclothymia among adolescents is estimated to be 0.85% (27) and rates of bipolar II disorder are estimated to be 1.1% among adults (28). Subthreshold symptoms of bipolar disorder were endorsed by 5.7% of adolescents in the Oregon Depression Study (27) and between 2.4% and 6% in adult samples (28, 29). Notably, subthreshold symptoms do not appear to convert to full-blown mania when patients are followed longitudinally (30).

Over the past decade, there has been a significant increase in the diagnosis of pediatric bipolar disorder across inpatient and outpatient clinical settings. A recent study of outpatient physician visits in the United States found that cases of bipolar disorder in children and adolescents comprised 6.67% of outpatient mental health related visits in 2003, an increase from 0.42% of cases in the early 1990s (2). A second study using data from the National Hospital Discharge Survey found that the rate at which bipolar disorder was diagnosed among children hospitalized for mental illness increased from 10% in 1996 to 34.11% in 2004 and from 10.24% to 25.86% among hospitalized adolescents during that same period (1). Findings suggested that the increase in bipolar disorder reflected a shift in diagnostic practices such that children and adolescents with affective aggression who might previously have been conceptualized as having conduct problems or troubled parent-child relationships, are now, for a variety of reasons, being diagnosed as having bipolar disorder.

COMORBIDITIES

Children and adolescents meeting the criteria for bipolar disorder nearly always present with co-occurring conditions. There has been a great deal of debate as to whether common comorbidities in youth with bipolar disorder represent truly separate diagnoses or may be an artifact of overlapping symptoms (31, 32). Indeed, even with a good history, it can be challenging to distinguish between symptoms of mania and its most common comorbidities. ADHD is the most frequently diagnosed comorbidity among children with bipolar disorder, with published rates exceeding 90% among preadolescent youth and 50% among adolescents (33–35). Rates of conduct disorder and oppositional defiant disorder are reported to be as high as 79% (36). This combination of externalizing disorders and bipolar disorder appears to run in families and is associated with significant functional morbidity (37). Comorbid anxiety disorders have been reported in up to 77% of children with narrow phenotype bipolar disorder, with particularly high rates of generalized anxiety disorder, separation anxiety, and specific phobia (38). There is some evidence that, in a number of youth, anxiety symptoms may intensify during episodes of depression and mania and resolve when mood symptoms are effectively treated (35). Finally, features of pervasive developmental disorders appear to be quite common among youth diagnosed with bipolar spectrum conditions (39), with one study reporting that approximately 20% of their sample met full criteria for a comorbid autism spectrum condition (40).

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Distinguishing between mania and other conditions of childhood is complicated by overlapping symptoms and by the confounding influences of development itself. At the center of the debate regarding symptom overlap has been a focus on differentiating between symptoms of ADHD and mania (41, 42). At this point, several studies have shown that these two conditions are distinct and separable (32, 43). However, in practice, mental health professionals may continue to struggle with the question of how to categorize certain behaviors. Indeed, a detailed history and symptom ascertainment are often required to distinguish between the disinhibited silliness of a child with ADHD and the euphoric mood associated with mania. Similarly, impulsivity can closely resemble the pleasure-seeking behaviors of mania, and resistance to bedtime must be distinguished from decreased need for sleep (see reference 4 for a review). There is some question as to whether rage episodes may be diagnostic of bipolar disorder in youth (15). Although it is true that rages can occur in manic individuals of any age, as an isolated symptom explosive irritability (presumably the affect underlying rage episodes) is common in a variety of childhood conditions and thus has poor discriminatory power (32). Therefore, although parents often refer to rages as “mood swings,” these should not be interpreted as sufficient evidence of a manic episode. Indeed, Mick et al. (16) found that although extreme explosiveness or “super” angry/grouchy/cranky irritability was common among children with mania, the majority of youth exhibiting these behaviors did not meet the full diagnostic criteria for a bipolar spectrum condition. Similarly, G. A. Carlson et al. (unpublished 2008 data) conducted a pilot study of children referred specifically to “rule out bipolar disorder” (N=33) and found that those youth with the most severe rage episodes (N=8) were a diagnostically heterogeneous group, with 25% meeting the criteria for mania with comorbid ADHD, 25% meeting the criteria for major depressive disorder with comorbid ADHD, 25% with pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified and ADHD, and 25% with pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified and major depressive disorder.

The issue of differential diagnosis of pediatric bipolar disorder is further complicated by the fact that affective and behavioral symptoms may be exacerbated by the emergence of new developmental demands and changing circumstances. Indeed, children with attention or learning challenges may begin to look increasingly dysregulated with the heightened demands of late elementary or middle school. Similarly, irritability may intensify in conjunction with increasing environmental challenges, such as difficulties with family and peer relationships. Moreover, symptoms similar to pediatric mania have been found among maltreated children (reviewed in reference 4), and therefore clinicians may struggle to determine whether presenting behaviors are sequelae of the abuse, symptoms of an emerging bipolar disorder, or both. In adolescents with severe psychotic symptoms, schizophrenia and substance-induced psychosis must be considered. Detailed information regarding history and longitudinal course of symptoms is necessary to distinguish such behavioral changes from the onset of a true mood disorder. In many instances, diagnostic clarity may only come with extended longitudinal follow-up.

COURSE

Converging evidence from short-term clinical and community studies suggests that early-onset bipolar spectrum conditions are characterized by slow response to treatment, persistent mood fluctuations, high rates of recurrence, elevated risk for suicide attempts, and severe psychosocial impairment (19, 44–49). Rates of remission in early-onset samples range from 65% within an adolescent community sample at a 2-year follow-up to 100% among hospitalized adolescents after 5 years. Among those children and adolescents who achieve remission, rates of relapse range from 27% among community-based adolescents at a 2-year follow-up to 70% among child and adolescent outpatients at a 4-year follow-up. Psychosocial impairment is most profound among the youngest patients with the diagnosis of bipolar disorder, and response to treatment is less robust, with fewer than half of children sampled experiencing remission at a 6- and 12-month follow-up. Moreover, even when symptoms have been alleviated, subthreshold symptoms of mania and depression often persist between episodes, as do symptoms of comorbid conditions and are associated with significant functional impairment (44–47)

Several risk and protective factors have been identified that appear to affect the course of bipolar spectrum conditions in youth. In a study of adolescent inpatients admitted for a manic or mixed episode, nonadherence to pharmacological treatment significantly decreased the chances of recovery (48). Notably, there was a 65% noncompliance rate within this sample. Recovery rates were further decreased by the presence of low socioeconomic status, comorbid anxiety, ADHD, and/or disruptive behavior disorders. Although alcohol use disorders and exposure to antidepressants were associated with increased risk of recurrence, involvement in psychotherapy appeared to have a protective effect. Interestingly, male adolescents appeared to have a less severe course with greater chance of recovery from the initial episode compared with female adolescents. Rapid cycling has also been identified as a poor prognostic indicator among adolescents hospitalized for bipolar illness (46).

Additional risk factors have been identified in outpatient samples. Geller et al. (19) found that a low level of maternal warmth was the strongest predictor of relapse, whereas psychotic symptoms predicted a more chronic course. In the largest naturalistic follow-up study of bipolar youth, Birmaher et al. (45) identified several risk factors for poor outcome, including low socioeconomic statis, early age of onset, prepubertal status at time of onset, psychotic symptoms, and female gender. Compared with children with bipolar I or II disorder, those with bipolar disorder not otherwise specified were found to have a more chronic course of illness with persistent subthreshold symptoms, and slower response to acute treatment. Notably, one-quarter of individuals with the initial diagnosis of bipolar disorder not otherwise specified converted to bipolar I or II disorder by the conclusion of the 2-year follow-up period.

Long-term follow-up studies are needed to examine continuity between childhood and adult bipolar phenotypes. At this point, there have been no studies that have tracked the course of narrow phenotype bipolar disorder from childhood through adulthood. However, findings from one small-scale study that followed adolescents with bipolar spectrum conditions into young adulthood suggest that symptom profiles with closer resemblance to classic bipolar disorder have a greater degree of stability over time (30).

ASSESSMENT AND TREATMENT

Assessment

Making an accurate diagnosis of bipolar disorder in children requires systematic and thoughtful evaluation procedures that go well beyond the simple application of DSM-IV-TR criteria for mania and depression. As with any serious psychiatric disorder, a thorough evaluation of pediatric bipolar disorder includes the administration of screening measures, interviews with caregiver(s) and child, and review of other diagnostic information. Screening instruments should be completed by multiple informants across settings (14). Although parent report on screening instruments has been found to be a more powerful predictor of bipolar diagnosis than youth self-report or teacher report (50), a diagnosis of bipolar disorder is most likely when there is teacher and parent agreement regarding manic symptomatology (51). Screening instruments that specifically ask about symptoms of bipolar disorder are most effective in discriminating bipolar disorder from non-bipolar disorders. Those with the highest diagnostic efficiency (50) include the parent-report General Behavior Index (PGBI) (52) and the Parent-Report Mood Disorders Questionnaire (P-MDQ) (53). More general screening instruments, such as the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) (54) or the Child Symptom Inventory (CSI-4) (54) can be extremely useful in detecting threshold and subthreshold conditions that frequently co-occur, or are often confused with mania such as anxiety disorders, ADHD, oppositional defiant disorder, pervasive developmental disorders, and conduct problems (4).

Ideally, assessment of pediatric bipolar disorder should always include direct interviews with caregivers and child. It is most useful to interview caregivers first, as they are likely to provide the most reliable information, and this material can be presented during the child interview to address any discrepant responses. Caregiver interviews should include an overview of current symptoms, developmental history, and longitudinal course (4). It is imperative that the evaluator have a working knowledge of normative and atypical child development across domains of functioning to determine whether reported behaviors are within expected limits given the child's current stage of development. Structured and semistructured diagnostic interviews are used in research settings to elicit symptoms of bipolar disorder and other childhood conditions and may also be useful in clinical settings (14). The most commonly used interviews are the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children (K-SADS) (55) and the Washington University in St. Louis Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia (WASH-U-KADS) (56). According to the AACAP Practice Parameters, when making a diagnosis of bipolar I or II disorder in children and adolescents, one should adhere to the DSM-IV-TR criteria, including duration. Moreover, the presence of cardinal symptoms of euphoria, grandiosity, and irritability should clearly represent a change from baseline functioning, “rather than reactions to situations, temperamental traits, negotiation strategies, or anger outbursts” (14). Clinical judgment is an essential component in administering semistructured interviews and is often required to determine whether a respondent is under- or overreporting symptoms, making developmentally expected behaviors pathological, or misinterpreting questions about clinical behaviors (50). To this end, it is critical that clinicians probe beyond affirmative responses to elicit examples of specific behaviors, as well as the context in which behaviors are occurring.

Family history of mood disorder, bipolar and unipolar, and other psychiatric disorders (including common disorders of childhood such as oppositional defiant disorder, ADHD, learning disabilities, and pervasive developmental disorders) must be assessed as part of the parent interview. If there is a positive family history for bipolar disorder, it is important to probe for details regarding clinical presentation, comorbid conditions, and response to treatment.

Although the most pertinent information regarding symptoms of mania and depression may come from the parent interview, the child interview is critical for eliciting important information regarding environmental factors contributing to mood variability, as well as features of other conditions that may be confused, or co-occur, with mania, including pervasive developmental disorder, language, or thought disorder, psychosis, anxiety, suicidal behavior, physical/sexual abuse, and illicit substance use.

Finally, collecting information from collateral sources and reviewing previous evaluation reports is essential whenever one is assessing bipolar disorder in children. In particular, input from teachers is necessary to determine whether manic-like symptoms are occurring across settings. Where there are discrepancies between parent and teacher report, home and school observation can be useful. Outside assessment reports can also be extremely helpful in identifying developmental, cognitive, and medical factors that may be contributing to emotional dysregulation. These may include neuropsychological, occupational therapy, psychoeducational, speech and language assessments, and medical records. It may also be useful to obtain a sleep-deprived electroencephalogram, a sleep electroencephalogram for sleep apnea, a thorough neurological assessment, or laboratory tests. In some cases, such assessments may be readily available, whereas in others the interviewer may recommend additional testing to complete the diagnostic evaluation.

PHARMACOLOGICAL TREATMENTS

Until recently, treatment recommendations for bipolar disorder in youth were based on data from adults. Over the past several years, paralleling the increased interest in this disorder, considerably more information has been generated. In particular, several large-scale open trials, a few small controlled trials, and increasingly, large, multisite industry sponsored trials are becoming available. Because of their importance, in the following summary, we will report results from recent poster presentations assuming that peer reviewed publications will follow. Attempts to summarize emerging findings can be found in a recent consensus statement (57) and AACAP's updated Practice Parameters for treatment of bipolar disorder (14).

Treatment algorithms and evidence-base reviews require an understanding of the difference between bipolar disorder (which is a lifetime diagnosis) and acute mania, which has been the focus of medication trials in most (but not all) publications. It is critical that one read the Methods section of any publication to determine whether the study is treating an acute, hospitalized sample (as is often the case in adult trials), an outpatient sample (which characterizes many child and adolescent trials), severe mania, mania, and hypomania (which characterizes some trials), lifetime mania where the focus is on prevention of future episodes, or the depressed phase of bipolar disorder.

As of 2007, eight medications have Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval for the treatment of acute mania in adults, two have approval for bipolar depression, and two have approval for maintenance treatment. Until this year, only lithium had been approved for adolescent mania and that approval was obtained before data were required to establish efficacy and safety in the age group in question. Importantly, as part of the Best Pharmaceutical Act for Children, there are now requirements to test medications for safety and effectiveness in children and adolescents, if there is an expectation of medication use in that age group. A consensus meeting was convened in 2002 (58) to provide guidelines as to how such studies should be executed in children. These guidelines were ultimately adopted in large part by the FDA and became part of the written requests made to companies in which a drug had been approved for treatment of mania in adults. The labeling requirement was that the condition, in this case, mania, had to be the same condition that existed in adults and that, by and large, similar measures to test safety and efficacy would be valid in that age group. The recommendations outlined in the conference proceedings were as follows: “To assign priority to placebo-controlled studies of acute manic episodes in children and adolescents aged 10–17 years [the age group that most felt mania as it occurred in adults could be diagnosed], who may or may not be hospitalized [recognizing that inpatient treatment was often not available and would limit study participation], and who may or may not suffer from common comorbid psychiatric disorders [acknowledging the high rates of comorbidity]; to require that specialist diagnostic “gatekeepers” screen youths' eligibility to participate in trials; to monitor interviewer and rater competency over the course of the trial using agreed upon standards; and to develop new tools for assessment, including scales to measure aggression/rage and cognitive function, while using the best available instruments (e.g., Young Mania Rating Scale) in the interim” (p. 14).

Mania trials are usually short term (3–8 weeks) depending on the medication. Atypical antipsychotic drugs tend to have shorter trials, with lithium and anticonvulsants having longer trials. In both child and adult studies, efficacy has been measured in three ways: 1) change from baseline on the Young Mania Rating Scale (Y-MRS) (59), 2) “response,” which is a 50% reduction in Y-MRS entry scores (averaging about 30), and 3) “remission,” which is variously defined as a Y-MRS score <12, a Clinical Global Improvement score for manic symptoms rating the child as improved or very much improved, or both. Unlike adult trials, which are usually conducted with hospitalized patients, child and adolescent trials have focused on outpatient samples. Both parent and child serve as informants on outcome measures, and the highest score from either is counted. Completion rates of adult studies have been approximately 50% or less. Completion rates in child and teen studies are between 60% and 80%.

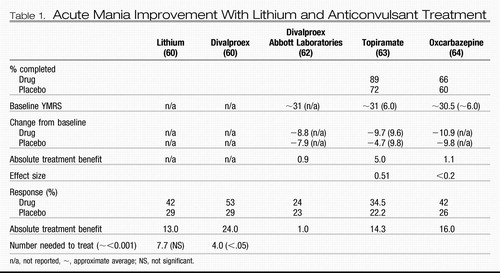

Currently, there have been no published placebo-controlled studies of lithium or divalproex in youth. Data have recently been presented at national meetings but have not yet been completely analyzed or peer reviewed. Nevertheless, lithium and divalproex have topped the list of treatments for children with bipolar disorder. The results from unpublished placebo-controlled (and one head-to-head) trials are summarized in Table 1. The study of lithium, divalproex, and placebo, recently completed by Kowatch et al. (60) mirrored a somewhat similar open trial done a number of years ago. In that 8-week open trial of 42 outpatient children and adolescents with mania and hypomania, which included carbamazepine rather than placebo, the response rate was 38% for lithium and carbamazepine and 53% for divalproex (61). The placebo-controlled trial (60), also 8 weeks, included more subjects (N=101) and reported a lithium response of 42%, a divalproex response of 53%, and a placebo response of 29%. Only the divalproex and placebo difference was significant (p<0.05). Interestingly, results of an industry-sponsored trial requested by the FDA, which was only 4 weeks, were negative (drug and placebo responses of 24% and 23%, respectively) (62). Published trials of two other anticonvulsants, topiramate and oxcarbazepine, reported that these medications were not significantly better than placebo (63, 64). The topiramate study, done only with adolescents who were included as part of a trial in adults, was considered underpowered (N=56). The oxcarbazepine study, although industry-sponsored, was not done in response to an FDA request. The sample included children down to age 7. The changes from baseline scores for drug and placebo on the Y-MRS were almost identical.

|

Table 1. Acute Mania Improvement With Lithium and Anticonvulsant Treatment

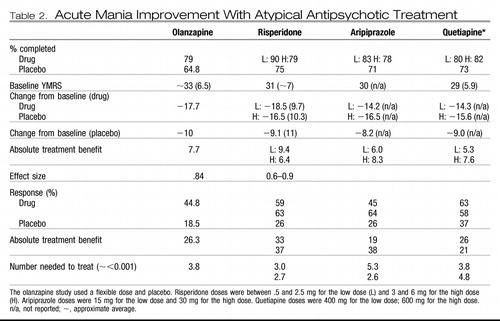

Four atypical antipsychotic medication trials have been completed for pediatric bipolar disorder (Table 2), all in response to an FDA written request (65–68). Olanzapine was tested in adolescents, as their written request had been issued before the FDA decision to include children down to age 10 (68). With doses ranging between 10 and 20 mg, 44.8% of youth receiving olanzapine showed at least a 50% reduction in symptoms compared to a placebo response rate of 18.5%. Other atypical antipsychotic trials were required to use low- and highdose alternatives. Results have been presented at national meetings but are as yet unpublished (65–67). Both high and low doses were effective as measured by a 50% reduction in Y-MRS entry scores. In general, 45%–64% of subjects improved when they received active medication versus 18.5%–37% of those receiving placebo. The absolute treatment benefit (percentage of drug responders minus placebo responders) averaged 19%–38%. Side effects were usually greater for the high-dose condition without a correspondingly higher improvement.

|

Table 2. Acute Mania Improvement With Atypical Antipsychotic Treatment

Open trials of lithium to treat mania in psychiatrically hospitalized youth have been examined. In a study of 100 hospitalized teens, 55% demonstrated a 50% reduction in the Y-MRS over 4 weeks (69). Once discharged and randomly assigned only to either placebo or lithium maintenance, however, both groups relapsed at the same rate (70). A separate, earlier study suggested that adjunctive antipsychotic treatment helped prevent relapse (71).

Divalproex has appeared to be effective in small, open trials, and in controlled trials but without a placebo arm (72, 73). A 6-month open trial demonstrated a response rate of 73% (74) and in an open discontinuation study, 61% of patients improved over the 8–10 weeks of the study (62).

Given that most children and teens with the diagnosis of bipolar disorder exhibit high levels of impairment, improvements in functioning, when they occur, are noteworthy, but are often insufficient. Increasingly, it has become acceptable to treat mania/bipolar disorder in both adults and young people using more than one medication. In youth, there are three types of studies used to examine the effectiveness of using multiple medications to treat early-onset bipolar illness: 1) comparing two medications to one (75); 2) adding one to another if the first drug does not work (76); and 3) starting two medications together and discontinuing one (77). In an example of the third type of study, lithium and divalproex were initiated together as part of a maintenance treatment study, and discontinuation of either drug appeared to result in relapse. Thus, findings suggest that the impact of this combination of medications is additive, both in effectiveness, but also in side effects.

Mania and/or ADHD.

When comorbidities are present, consensus documents (14, 57) recommend stabilizing the mood disorder symptoms and then treating the comorbid disorder. ADHD is the only condition that has been systematically studied in children with mania or bipolar disorder not otherwise specified. A recent meta-analysis (78) showed that comorbid ADHD lowered treatment responsiveness to the bipolar disorder intervention. This finding suggests that the ADHD needs to be addressed. Although there have been concerns about treating ADHD in children with definite or possible mania, an increasing number of studies are substantiating the utility of doing so either with or without prior mood stabilization (73, 79–82).

Bipolar depression.

Treatment of bipolar depression in young people has received little attention. In one open trial of lithium monotherapy for hospitalized adolescents with bipolar depression, there was a reduction in depressive symptoms, although most of this occurred during the first or second week of hospitalization (83). There is also a positive open trial using lamotrigine alone or with other medication in adolescents (84). There are no placebo-controlled studies, and a high placebo response was responsible for two trials of lamotrigine with negative results in adults with bipolar depression (reviewed in reference 85). Moreover, the adolescent participants were likely to be presenting with mixed episodes (Y-MRS scores were >12) in contrast with the adults whose Y-MRS scores were approximately 2. Thus, it is not possible to extrapolate intelligently from adult data.

Maintenance.

Young people with bipolar disorder have higher relapse rates and more episodes over the course of 1 year than adults (44). The only purely maintenance study done, comparing lithium and divalproex alone after a child's condition was stabilized on both medications, indicated poor maintenance of mood stability (86). The 6 -month components of industry-sponsored studies are being analyzed and are not yet available. The question of how best to maintain stability of mood after treatment response, then, is not clear other than to assume that whichever treatment stabilized the child's condition should be continued for as long as possible.

PSYCHOSOCIAL TREATMENT

The AACAP treatment guidelines emphasize the importance of incorporating psychosocial intervention strategies into any comprehensive treatment plan for pediatric bipolar spectrum conditions (14). To address impairments in academic and social functioning, developmental issues, and family dynamics and to increase compliance with medication treatment. There are four models of psychosocial treatment that have been studied in children and adolescents with pediatric bipolar disorder; these are multifamily psychoeducation groups (MFPG) and individual family psychoeducation (IFP) (87), family-focused therapy for adolescents (FFT-A) (88), child- and family-focused cognitive behavior therapy for younger children (CFF-CBT) (89, 90), and collaborative problem solving (CPS) (R. Greene, unpublished 2008 data). Although distinct in a number of ways, these interventions share common ingredients that reflect the needs of children with pediatric bipolar illness and their families. Each emphasizes the importance of psychoeducation, as well as a focus on destigmatization and decreasing the tendency to blame children and/or parents for causing the disorder (87). Other components include helping parents distinguish between normative developmental behavior and bipolar symptoms, taking proactive steps to decrease risk of relapse, developing tools for effectively managing emotional arousal, improving family communication skills, and teaching adaptive problem-solving strategies.

At this point, findings from randomized controlled and open trials suggest positive effects from acute psychosocial treatment, with sustained improvement over the course of maintenance sessions. A series of randomized controlled trials of MFPG and IFP showed that IFP resulted in decreased mood symptoms and improved family climate, whereas MFPG yielded improvements in family interaction and parents' ability to obtain appropriate services (87). Unpublished findings from a recent trial of collaborative problem solving indicate that children who received CPS only and CPS+medication exhibited posttreatment improvements in manic symptoms, oppositional behavior, and social and academic functioning. Children in the CPS-only group showed additional improvements in conduct problems, whereas parents in this group reported decreased stress and lower levels of expressed emotion. Decreases in manic and depressive symptoms were most significant among those who received both CPS and medication. A series of open trials of FFT-based therapies were also suggestive of positive effects. A 2-year follow-up study of adolescents who, in addition to medication management, received 9 months of active FFT-A, followed by 15 months of trimonthly booster sessions, revealed a significant and sustained decrease in symptoms of mania, depression, and parent-reported problem behaviors over the course of treatment. Notably, high levels of expressed emotion and interpersonal life stress were predictive of decreased treatment benefits (88, 91–93). Pavuluri et al. (90) conducted an open trial of the 12-week acute phase of CFF-CBT combined with pharmacological treatment and found that participants reported decreased symptoms of mania and depression, as well as improved social and academic functioning. A recent follow-up study of this same sample showed sustained positive treatment effects after a 3-year maintenance phase (89).

QUESTIONS AND CONTROVERSIES

The growing interest in early-onset bipolar disorder is important for a myriad of reasons. From a clinical standpoint, the group of children being labeled as having bipolar disorder have significantly impairing problems that need attention now. The appeal of calling those problems “bipolar” is that we, as clinicians, then have the impression that we know what is wrong with the children and we can adopt strategies that are helpful for adults and understand the long-term course of the condition. It is our view, however, that it is premature to draw such conclusions. Whereas it is not good to miss the diagnosis of bipolar disorder, it is equally egregious to miss something else or to treat someone for something they do not have. An alternative conceptualization is that what is being called bipolar disorder represents a developmental disorder of emotion regulation, which is less diagnostically specific but equally important to understand. Before we conclude that these conditions are the same, we need to know whether the childhood phenotype is continuous with classic adult bipolar disorder or complex, mixed, rapid cycling bipolar disorder. From our reading of the literature and experience with long-term follow up, there are no data to suggest the former, but the latter has not been ruled out.

Researchers have attempted to validate early-onset bipolar disorder by comparing it with other childhood conditions, most often ADHD, but sometimes anxiety or conduct disorder. However, until severity and comorbidity are controlled, it is impossible to know whether bipolar is just another word for the most severe and complex condition.

Finally, it is our contention that some of the controversy around defining bipolar disorder in youth has to do with assumptions about development and application of the adult criteria to children. Although attempts to describe the clinical presentation of cardinal symptoms in children have helped to increase reliability within research settings, further studies are required to determine the normative parameters of these behaviors at various developmental stages and to assess the frequency with which they may be present in other childhood-onset conditions. Moreover, additional research is needed to assess the degree to which developmental factors may affect children's abilities to comprehend and accurately describe such complex symptoms in the context of a semistructured interview.

RECOMMENDATIONS FROM THE AUTHORS

At the present historical juncture, there is growing acceptance of the existence of bipolar disorder in children and adolescents. However, from our understanding of the current literature and from evaluating many children referred with mood problems, it is clear that not everyone who appears to meet the criteria for childhood mania at first glance merits a diagnosis of bipolar disorder. There may be a variety of psychosocial, developmental, neurocognitive, psychiatric, biological, and/or historical factors contributing to a clinical presentation characterized by aggression, irritability, and emotional dysregulation. We encourage mental health professionals who are considering a diagnosis of early-onset bipolar spectrum disorder to go beyond standardized adult criteria to gain in-depth understanding of a child's developmental history and longitudinal course of symptoms and the current and historical contexts in which behaviors are being expressed. This can often be a challenging and time-consuming endeavor, and answers are rarely clear-cut. One can maximize the chances of successful clinical outcomes by utilizing empirically supported assessment tools, by employing sound clinical judgment, and by developing collaborative relationships with parents and children in attempting to understand the child's condition and to determine the most effective course of treatment. We also strongly encourage professionals treating early-onset bipolar spectrum conditions to always work within the context of a multidisciplinary treatment team, involving, among others, relevant school personnel, case managers, individual therapists, family therapists, neuropsychologists, occupational therapists, and speech and language specialists. In our experience, most juvenile-onset cases of bipolar disorder involve a complex interplay among transactional vulnerability factors that cannot be adequately managed with a single approach to assessment and treatment.

1 Blader J, Carlson GA: Increased rates of bipolar disorder diagnoses among U.S. child, adolescent, and adult inpatients, 1996–2004. Biol Psychiatry 2007; 62: 104– 106Crossref, Google Scholar

2 Moreno C, Laje G, Blanco C, Jiang H, Schmidt AB, Olfson M: National trends in the outpatient diagnosis and treatment of bipolar disorder in youth. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2007; 64: 1032– 1039Crossref, Google Scholar

3 Findling R, Post R, Carlson GA. Protective and risk factors in pediatric bipolar disorder: predicting outcomes, in Proceedings of the 53rd Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. Washington, DC, American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 2006Google Scholar

4 Carlson GA, Meyer SE: Diagnosis of bipolar disorder across the lifespan: complexities and developmental issues. Dev Psychopathol 2006; 18: 939– 969Crossref, Google Scholar

5 Glovinsky I: A brief history of childhood-onset bipolar disorder through 1980. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin North Am 2002; 11: 443– 460Crossref, Google Scholar

6 Kraepelin E. Manic-depressive insanity and paranoia. Edinburgh, Scotland, Livingstone, 1921Google Scholar

7 Kasanin J. The affective psychoses in children. Am J Psychiatry 1931; 87: 897– 926Crossref, Google Scholar

8 Anthony J, Scott P: Manic-depressive psychosis in childhood. Child Psychol Psychiatry 1960; 1: 53– 72Crossref, Google Scholar

9 Youngerman J, Canino IA: Lithium carbonate use in children and adolescents: a survey of the literature. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1978; 35: 216– 224Crossref, Google Scholar

10 Weinberg WA, Brumback RA: Mania in childhood. Am J Dis Child 1976; 130: 380– 385Crossref, Google Scholar

11 Davis RE: Manic-depressive variant syndrome of childhood: a preliminary report. Am J Psychiatry 1979; 136: 702– 706Crossref, Google Scholar

12 Judd LL, Akiskal HS, Schettler PJ, Endicott J, Maser J, Solomon DA, Leon AC, Rice JA, Keller MB. The long-term natural history of the weekly symptomatic status of bipolar I disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2002; 59: 530– 537Crossref, Google Scholar

13 Goodwin FK, Jamison KR. Manic-depressive illness. New York, Oxford University Press, 1990Google Scholar

14 McClellan J, Kowatch RA, Findling RL: Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with bipolar disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2007; 46: 107– 125Crossref, Google Scholar

15 Carlson GA: Who are the children with severe mood dysregulation, a.k.a. “rages”? Am J Psychiatry 2007; 164: 1140– 1142Crossref, Google Scholar

16 Mick E, Spencer T, Wozniak J, Biederman J: Heterogeneity of irritability in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder subjects with and without mood disorders. Biol Psychiatry 2005; 58: 576– 582Crossref, Google Scholar

17 Leibenluft E, Charney DS, Towbin KE, Bhangoo RK, Pine DS: Defining clinical phenotypes of juvenile mania. Am J Psychiatry 2003; 160: 430– 437Crossref, Google Scholar

18 Rich BA, Schmajuk M, Perez-Edgar KE, Fox NA, Pine DS, Leibenluft E: Different psychophysiological and behavioral responses elicited by frustration in pediatric bipolar disorder and severe mood dysregulation. Am J Psychiatry 2007; 164: 309– 317Crossref, Google Scholar

19 Geller B, Tillman R, Craney JL, Bolhofner K: Four-year prospective outcome and natural history of mania in children with a prepubertal and early adolescent bipolar disorder phenotype. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2004; 61: 459– 467Crossref, Google Scholar

20 Biederman J, Mick E, Faraone SV, Spencer T, Wilens TE, Wozniak J: Pediatric mania: a developmental subtype of bipolar disorder? Biol Psychiatry 2000; 48: 458– 466Crossref, Google Scholar

21 Dubicka B, Carlson G, Vail A, Harrington R. Prepubertal mania: diagnostic differences between US and UK clinicians. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry (in press)Google Scholar

22 Geller B, Tillman R, Bolhofner K: Proposed definitions of bipolar I disorder episodes and daily rapid cycling phenomena in preschoolers, school-aged children, adolescents, and adults. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 2007; 17: 217– 222Crossref, Google Scholar

23 Geller B, Zimerman B, Williams M, DelBello MP, Frazier J, Beringer L: Phenomenology of prepubertal and early adolescent bipolar disorder: examples of elated mood, grandiose behaviors, decreased need for sleep, racing thoughts, and hypersexuality. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 2002; 12: 3– 9Crossref, Google Scholar

24 Costello EJ, Angold A, Burns BJ, Stangl DK, Tweed DL, Erkanli A, Worthman CM. The Great Smoky Mountains Study of Youth: goals, design, methods, and the prevalence of DSM-III-R disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1996; 53: 1129– 1136Crossref, Google Scholar

25 Brotman MA, Schmajuk M, Rich BA, Dickstein DP, Guyer AE, Costello EJ, Egger HL, Angold A, Pine DS, Leibenluft E. Prevalence, clinical correlates, and longitudinal course of severe mood dysregulation in children. Biol Psychiatry 2006; 60: 991– 997Crossref, Google Scholar

26 Carlson GA, Kashani JH: Manic symptoms in a non-referred adolescent population. J Affect Disord 1988; 15: 219– 226Crossref, Google Scholar

27 Lewinsohn PM, Klein DN, Seeley JR: Bipolar disorders in a community sample of older adolescents: prevalence, phenomenology, comorbidity, and course. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1995; 34: 453– 463Google Scholar

28 Merikangas KR, Akiskal HS, Angst J, Greenberg PE, Hirschfeld RM, Petukhova M, Kessler RC. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of bipolar spectrum disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2007; 64: 543– 553Crossref, Google Scholar

29 Hirschfeld RM, Vornik LA. Recognition and diagnosis of bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2004; 65 ( suppl): 5– 9Google Scholar

30 Lewinsohn PM, Klein DN, Seeley JR: Bipolar disorder during adolescence and young adulthood in a community sample. Bipolar Disord 2000; 2: 281– 293Crossref, Google Scholar

31 Milberger S, Biederman J, Faraone SV, Murphy J, Tsuang MT: Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and comorbid disorders: issues of overlapping symptoms. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152: 1793– 1799Crossref, Google Scholar

32 Geller B, Zimerman B, Williams M, DelBello MP, Bolhofner K, Craney JL, Frazier J, Beringer L, Nickelsburg MJ. DSM-IV mania symptoms in a prepubertal and early adolescent bipolar disorder phenotype compared to attention-deficit hyperactive and normal controls. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 2002; 12: 11– 25Crossref, Google Scholar

33 Tillman R, Geller B, Bolhofner K, Craney JL, Williams M, Zimerman B: Ages of onset and rates of syndromal and subsyndromal comorbid DSM-IV diagnoses in a prepubertal and early adolescent bipolar disorder phenotype. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2003; 42: 1486– 1493Crossref, Google Scholar

34 Faraone SV, Biederman J, Wozniak J, Mundy E, Mennin D, O'Donnell D: Is comorbidity with ADHD a marker for juvenile-onset mania? J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1997; 36: 1046– 1055Crossref, Google Scholar

35 Findling RL, Gracious BL, McNamara NK, Youngstrom EA, Demeter CA, Branicky LA, Calabrese JR. Rapid, continuous cycling and psychiatric co-morbidity in pediatric bipolar I disorder. Bipolar Disord 2001; 3: 202– 210Crossref, Google Scholar

36 Wilens TE, Biederman J, Forkner P, Ditterline J, Morris M, Moore H, Moore H, Galdo M, Spencer TJ, Wozniak J. Patterns of comorbidity and dysfunction in clinically referred preschool and school-age children with bipolar disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 2003; 13: 495– 505Crossref, Google Scholar

37 Faraone SV, Biederman J, Mennin D, Russell R: Bipolar and antisocial disorders among relatives of ADHD children: parsing familial subtypes of illness. Am J Med Genet 1998; 81: 108– 116Crossref, Google Scholar

38 Dickstein DP, Rich BA, Binstock AB, Pradella AG, Towbin KE, Pine DS, Leibenluft C. Comorbid anxiety in phenotypes of pediatric bipolar disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 2005; 15: 534– 548Crossref, Google Scholar

39 Towbin KE, Pradella A, Gorrindo T, Pine DS, Leibenluft E: Autism spectrum traits in children with mood and anxiety disorders. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 2005; 15: 452– 464Crossref, Google Scholar

40 Wozniak J, Biederman J, Faraone SV, Frazier J, Kim J, Millstein R, Gershon J, Thornell A, Cha K, Snyder JB. Mania in children with pervasive developmental disorder revisited. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1997; 36: 1552– 1559Google Scholar

41 Carlson GA: Mania and ADHD: comorbidity or confusion. J Affect Disord 1998; 51: 177– 187Crossref, Google Scholar

42 Biederman J, Klein RG, Pine DS, Klein DF: Resolved: mania is mistaken for ADHD in prepubertal children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1998; 37: 1096– 1099Google Scholar

43 Spencer TJ, Biederman J, Wozniak J, Faraone SV, Wilens TE, Mick E: Parsing pediatric bipolar disorder from its associated comorbidity with the disruptive behavior disorders. Biol Psychiatry 2001; 49: 1062– 1070Crossref, Google Scholar

44 Birmaher B, Axelson D, Strober M, Gill MK, Valeri S, Chiappetta L, Ryan N, Leonard H, Hunt J, Iyengar S, Keller M. Clinical course of children and adolescents with bipolar spectrum disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2006; 63: 175– 183Crossref, Google Scholar

45 Birmaher B, Axelson D: Course and outcome of bipolar spectrum disorder in children and adolescents: a review of the existing literature. Dev Psychopathol 2006; 18: 1023– 1035Crossref, Google Scholar

46 Strober M, Schmidt-Lackner S, Freeman R, Bower S, Lampert C, DeAntonio M: Recovery and relapse in adolescents with bipolar affective illness: a five-year naturalistic, prospective follow-up. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1995; 34: 724– 731Crossref, Google Scholar

47 Biederman J, Mick E, Faraone SV, Van Patten S, Burback M, Wozniak J: A prospective follow-up study of pediatric bipolar disorder in boys with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Affect Disord 2004; 82S: S17– S23Crossref, Google Scholar

48 DelBello MP, Hanseman D, Adler CM, Fleck DE, Strakowski SM: Twelve-month outcome of adolescents with bipolar disorder following first hospitalization for a manic or mixed episode. Am J Psychiatry 2007; 164: 582– 590Crossref, Google Scholar

49 Lewinsohn PM, Seeley JR, Klein DN: Bipolar disorders during adolescence. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2003; 108 ( suppl 418): 47– 50Crossref, Google Scholar

50 Youngstrom E, Meyers O, Youngstrom JK, Calabrese JR, Findling RL: Diagnostic and measurement issues in the assessment of pediatric bipolar disorder: implications for understanding mood disorder across the life cycle. Dev Psychopathol 2006; 18: 989– 1021Crossref, Google Scholar

51 Carlson GA, Youngstrom EA: Clinical implications of pervasive manic symptoms in children. Biol Psychiatry 2003; 53: 1050– 1058Crossref, Google Scholar

52 Youngstrom EA, Findling RL, Danielson CK, Calabrese JR: Discriminative validity of parent report of hypomanic and depressive symptoms on the General Behavior Inventory. Psychol Assess 2001; 13: 267– 276Crossref, Google Scholar

53 Hirschfeld RM, Williams JB, Spitzer RL, Calabrese JR, Flynn L, Keck PE Jr, Lewis L, McElroy SL, Post RM, Rapport DJ, Russell JM, Sachs GS, Zajecka J. Development and validation of a screening instrument for bipolar spectrum disorder: the Mood Disorder Questionnaire. Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157: 1873– 1875Crossref, Google Scholar

54 Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA. Manual for the ASEBA School-Age Forms & Profiles. Burlington, University of Vermont, 2001Google Scholar

55 Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent D, Rao U, Flynn C, Moreci P, Williamson D, Ryan N. Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children-Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL): initial reliability and validity data. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1997; 36: 980– 988Crossref, Google Scholar

56 Geller B, Zimerman B, Williams M, Bolhofner K, Craney JL, DelBello MP, Soutello C. Reliability of the Washington University in St. Louis Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia (WASH-U-KSADS) mania and rapid cycling sections. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2001; 40: 450– 455Crossref, Google Scholar

57 Kowatch RA, Fristad M, Birmaher B, Wagner KD, Findling RL, Hellander M, Child Psychiatric Workgroup on Bipolar Disorders. Treatment guidelines for children and adolescents with bipolar disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2005; 44: 213– 235Crossref, Google Scholar

58 Carlson GA, Jensen PS, Findling RL, Meyer RE, Calabrese J, DelBello MP, Emslie G, Flynn L, Goodwin F, Hellander M, Kowatch R, Kusumakar V, Laughren T, Leibenluft E, McCracken J, Nottelmann E, Pine D, Sachs G, Shaffer D, Simar R, Strober M, Weller EB, Wozniak J, Youngstrom EA. Methodological issues and controversies in clinical trials with child and adolescent patients with bipolar disorder: report of a consensus conference. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 2003; 13: 13– 27Crossref, Google Scholar

59 Young RC, Biggs JT, Ziegler VE, Meyer DA: A rating scale for mania: reliability, validity and sensitivity. Br J Psychiatry 1978; 133: 429– 435Crossref, Google Scholar

60 Kowatch RA, Scheffer R, Findling RL. Placebo controlled trial of divalproex versus lithium for bipolar disorder, in 2007 Proceedings of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Annual Meeting. Washington, DC, American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 2007Google Scholar

61 Kowatch RA, Suppes T, Carmody TJ, Bucci JP, Hume JH, Kromelis M, Emslie GJ, Weinberg WA, Rush AJ. Effect size of lithium, divalproex sodium, and carbamazepine in children and adolescents with bipolar disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2000; 39: 713– 720Crossref, Google Scholar

62 Wagner KD, Redden L, Kowatch RA, Wilens TE, Segal S, Chang KD, Wozniak P, Vigna N, Schmitz PJ, Abi-Saab W, Saltorelli M. Safety and efficacy of divalproex ER in youth with mania, in 2007 Proceedings of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Annual Meeting. Washington, DC, American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 2007Google Scholar

63 Delbello MP, Findling RL, Kushner S, Wang D, Olson WH, Capece JA, Fazzio L, Rosenthal NR. A pilot controlled trial of topiramate for mania in children and adolescents with bipolar disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2005; 44: 539– 547Crossref, Google Scholar

64 Wagner KD, Kowatch RA, Emslie GJ, Findling RL, Wilens TE, McCague K, D'Souza J, Wamil A, Lehman RB, Berv D, Linden D. A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of oxcarbazepine in the treatment of bipolar disorder in children and adolescents. Am J Psychiatry 2006; 163: 1179– 1186Crossref, Google Scholar

65 DelBello FP, Findling RL, Earley WR, Acevedo LD, Stankowski J. Efficacy of quetiapine in children and adolescents with bipolar mania: a 3 week, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial, in 2007 Proceedings of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Annual Meeting. Washington, DC, American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 2007Google Scholar

66 Chang KD, Nyilas M, Aurang C, van Beck A, Jin N, Marcus R, Forbes RA, Carson WH, Kahn A, Findling RL. Efficacy of aripiprazole in children (10–17 years old) with mania, in Proceedings of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Annual Meeting. Washington, DC, American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 2007Google Scholar

67 Pandina GJ, DelBello MP, Kushner S, Van Hove I, Kusumakar V, Haas M, Augustyns I. Risperidone for the treatment of acute mania in bipolar youth, in Proceedings of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Annual Meeting. Washington, DC, American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 2007Google Scholar

68 Tohen M, Kryzhanovskaya L, Carlson G, Delbello M, Wozniak J, Kowatch R, Wagner K, Findling R, Lin d, Robertson-Plouch C, Xu W, Dittmann RW, Biederman J. Olanzapine versus placebo in the treatment of adolescents with bipolar mania. Am J Psychiatry 2007; 164: 1547– 1556Crossref, Google Scholar

69 Kafantaris V, Coletti DJ, Dicker R, Padula G, Kane JM: Lithium treatment of acute mania in adolescents: a large open trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2003; 42: 1038– 1045Crossref, Google Scholar

70 Kafantaris V, Coletti DJ, Dicker R, Padula G, Pleak RR, Alvir JM: Lithium treatment of acute mania in adolescents: a placebo-controlled discontinuation study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2004; 43: 984– 993Crossref, Google Scholar

71 Kafantaris V, Dicker R, Coletti DJ, Kane JM: Adjunctive antipsychotic treatment is necessary for adolescents with psychotic mania. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 2001; 11: 409– 413Crossref, Google Scholar

72 DelBello MP, Kowatch RA, Adler CM, Stanford KE, Welge JA, Barzman DH, et al. A double-blind randomized pilot study comparing quetiapine and divalproex for adolescent mania. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2006; 45: 305– 313Crossref, Google Scholar

73 Scheffer RE, Kowatch RA, Carmody T, Rush AJ: Randomized, placebo-controlled trial of mixed amphetamine salts for symptoms of comorbid ADHD in pediatric bipolar disorder after mood stabilization with divalproex sodium. Am J Psychiatry 2005; 162: 58– 64Crossref, Google Scholar

74 Pavuluri MN, Henry DB, Carbray JA, Naylor MW, Janicak PG: Divalproex sodium for pediatric mixed mania: a 6-month prospective trial. Bipolar Disord 2005; 7: 266– 273Crossref, Google Scholar

75 Delbello MP, Schwiers ML, Rosenberg HL, Strakowski SM: A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study of quetiapine as adjunctive treatment for adolescent mania. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2002; 41: 1216– 1223Crossref, Google Scholar

76 Pavuluri MN, Henry DB, Carbray JA, Sampson G, Naylor MW, Janicak PG. Open-label prospective trial of risperidone in combination with lithium or divalproex sodium in pediatric mania. J Affect Disord 2004; 82 ( suppl): S103– S111Crossref, Google Scholar

77 Findling RL, McNamara NK, Stansbrey R, Gracious BL, Whipkey RE, Demeter CA, Reed MD, Youngstrom EA, Calabrese JR. Combination lithium and divalproex sodium in pediatric bipolar symptom re-stabilization. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2006; 45: 142– 148Crossref, Google Scholar

78 Consoli A, Bouzamondo A, Guilé JM, Lechat P, Cohen D: Comorbidity with ADHD decreases response to pharmacotherapy in children and adolescents with acute mania: evidence from a meta-analysis. Can J Psychiatry 2007; 52: 323– 328Crossref, Google Scholar

79 Carlson GA, Rapport MD, Kelly KL, Pataki CS: The effects of methylphenidate and lithium on attention and activity level. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1992; 31: 262– 270Crossref, Google Scholar

80 Galanter CA, Pagar DL, Davies M, Li W, Carlson GA, Abikoff HB, Arnold LE, Bukstein OG, Pelham W, Elliott GR, Hinshaw S, Epstein JN, Wells K, Hechtman L, Newcorn JN, Greenhill L, Wigal T, Swanson JM, Jensen PS. ADHD and manic symptoms: diagnostic and treatment implications. Clin Neurosci Res 2005; 5: 283– 294Crossref, Google Scholar

81 Findling RL, Short EJ, McNamara NK, Demeter CA, Stansbrey RJ, Gracious BL, Gracious BL, Whipkey R, Manos MJ, Calabrese JR. Methylphenidate in the treatment of children and adolescents with bipolar disorder and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2007; 46: 1445– 1453Crossref, Google Scholar

82 Tillman R, Geller B: Controlled study of switching from attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder to a prepubertal and early adolescent bipolar I disorder phenotype during 6-year prospective follow-up: rate, risk, and predictors. Dev Psychopathol 2006; 18: 1037– 1053Crossref, Google Scholar

83 Patel NC, DelBello MP, Bryan HS, Adler CM, Kowatch RA, Stanford K, Strakowski SM. Open-label lithium for the treatment of adolescents with bipolar depression. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2006; 45: 289– 297Crossref, Google Scholar

84 Chang K, Saxena K, Howe M: An open-label study of lamotrigine adjunct or monotherapy for the treatment of adolescents with bipolar depression. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2006; 45: 298– 304Crossref, Google Scholar

85 Goodwin FK, Jamison KR. Manic-Depressive Illness Bipolar Disorders and Recurrent Depression. New York, Oxford University Press, 2007Google Scholar

86 Findling RL, McNamara NK, Youngstrom EA, Stansbrey R, Gracious BL, Reed MD, Calabrese JR. Double-blind 18-month trial of lithium versus divalproex maintenance treatment in pediatric bipolar disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2005; 44: 409– 417Crossref, Google Scholar

87 Fristad MA: Psychoeducational treatment for school-aged children with bipolar disorder. Dev Psychopathol 2006; 18: 1289– 306Crossref, Google Scholar

88 Miklowitz DJ, George EL, Axelson DA, Kim EY, Birmaher B, Schneck C, Beresford C, Craighead WE, Brent DA. Family-focused treatment for adolescents with bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord 2004; 82 ( suppl): S113– S128Crossref, Google Scholar

89 West AE, Henry DB, Pavuluri MN: Maintenance model of integrated psychosocial treatment in pediatric bipolar disorder: a pilot feasibility study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2007; 46: 205– 212Crossref, Google Scholar

90 Pavuluri MN, Graczyk PA, Henry DB, Carbray JA, Heidenreich J, Miklowitz DJ: Child- and family-focused cognitive-behavioral therapy for pediatric bipolar disorder: development and preliminary results. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2004; 43: 528– 537Crossref, Google Scholar

91 Kim EY, Miklowitz DJ: Expressed emotion as a predictor of outcome among bipolar patients undergoing family therapy. J Affect Disord 2004; 82: 343– 352Google Scholar

92 Kim EY, Miklowitz DJ, Biuckians A, Mullen K: Life stress and the course of early-onset bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord 2007; 99: 37– 44Crossref, Google Scholar

93 Miklowitz DJ, Biuckians A, Richards JA: Early-onset bipolar disorder: a family treatment perspective. Dev Psychopathol 2006; 18: 1247– 1265Google Scholar