Randomized Trial of Weekly, Twice-Monthly, and Monthly Interpersonal Psychotherapy as Maintenance Treatment for Women With Recurrent Depression

Abstract

Objectives:

The authors sought to determine whether a greater frequency of interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT) sessions during maintenance treatment has a greater prophylactic effect than a previously validated once-a-month treatment. Method: A total of 233 women 20–60 years of age with recurrent unipolar depression were treated in an outpatient research clinic. After participants had achieved remission with weekly IPT or, if required, with weekly IPT plus antidepressant pharmacotherapy, they were randomly assigned to weekly, twice-monthly, or monthly maintenance IPT monotherapy for 2 years or until a recurrence of their depression occurred. Results: Among participants who remitted with IPT alone and entered maintenance treatment (N = 99), 19 (26%) of the 74 who remained in the study throughout the 2-year maintenance phase experienced a recurrence of depression. Among participants who required the addition of a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor to achieve remission (N = 90), 32 (36%) sustained that remission through continuation treatment and drug discontinuation and began maintenance treatment; of these, 13 (50%) of the 26 who remained in the study throughout the maintenance phase experienced a recurrence. Survival analysis of time to recurrence by randomized treatment frequency showed no effect on recurrence-free survival in either treatment subgroup. Conclusions: These results suggest that maintenance IPT, even at a frequency of only one visit per month, is a good method of prophylaxis for women who can achieve remission with IPT alone. In contrast, among those who require the addition of pharmacotherapy, IPT monotherapy represents a significantly less efficacious approach to maintenance treatment.

(Reprinted with permission from the American Journal of Psychiatry 2007; 164:761–767)

The long-term treatment of recurrent depression has become an important focus of psychiatric research and practice. There is now substantial evidence that the most effective pharmacotherapeutic approach for prophylaxis is to maintain the full dose of the antidepressant with which remission was achieved (1–4). However, not all patients are willing or able to remain on maintenance pharmacotherapy indefinitely. Many women prefer treatment with psychotherapy (5, 6). Similarly, among patients with medical illnesses that require complex pharmacotherapy regimens, psychotherapy may be the preferred mode of treatment.

Jarrett et al. (7) and Hollon et al. (8) demonstrated the efficacy of continuation treatment “booster” sessions following acute treatment with cognitive therapy (9), and our own results (10) pointed to the possible utility of interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT) (11) as a long-term maintenance strategy. In our earlier study (12) examining the efficacy of maintenance IPT among patients randomly assigned to monthly sessions of maintenance IPT alone after acute treatment with IPT and imipramine, the median time to recurrence was 54 weeks in a 3-year maintenance phase. Among those whose treatment was characterized by ideal therapeutic conditions during sessions-that is, an intensive focus on interpersonal concerns-median survival time nearly doubled to 102 weeks. We observed similar benefits with maintenance IPT in a study of late-life patients (13).

Further development of nonpharmacologic preventive maintenance strategies is especially relevant for women, given the female-to-male prevalence ratio of approximately 2:1 for unipolar depression (14–16) and the preference of women for treatment with psychotherapy (5, 6), especially during the childbearing years, when concerns about teratogenesis or effects on the nursing infant may be prominent. The many psychosocial vulnerability factors for depressive relapse observed in women (17) make IPT an especially apt intervention for this population.

Previous studies of continuation or maintenance psychotherapy have not addressed the question of the appropriate frequency of sessions—or psychotherapy “dosage”—for prevention of relapse or recurrence. In our previous investigations (10, 13), we used once-a-month psychotherapy for maintenance treatment. It is yet to be determined whether maintenance psychotherapy is “dose dependent.” For individuals who achieve remission of their depressive episode with psychotherapy, is the ideal dose of maintenance psychotherapy weekly, twice monthly, or monthly? For individuals who receive a combination of pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy for acute treatment but wish to discontinue medication, what is the ideal maintenance dose of psychotherapy in the absence of maintenance pharmacotherapy? Given the cost and time involved in psychotherapy, on the one hand, and the psychological burden and impairment associated with a recurrence of depression, on the other, it is important to determine the lowest efficacious dose of maintenance psychotherapy for both these patient groups.

Our primary objective in this study was to determine the ideal frequency of maintenance interpersonal psychotherapy for women treated acutely with psychotherapy alone or, if necessary, with a combination of psychotherapy and medication. Maintenance IPT differs from acute IPT in the focus of sessions and, typically, in the frequency as well. In acute IPT, sessions focus on addressing one of four problem areas (grief, role transitions, role disputes, and interpersonal deficits), depending on the patient's presenting problem. In maintenance IPT, the focus is broader because the goal is prevention of recurrence and because therapy aims to augment the competencies and strengths achieved in acute IPT, helping the patient assume responsibility for the prevention of future episodes and reinforcing skills in coping with interpersonal life events while still focusing on the four traditional problem areas of IPT (11). In this study, we investigated the relative efficacy of three different “doses” of IPT for prophylaxis of new depressive episodes in women with histories of recurrent illness.

METHOD

PARTICIPANTS

A total of 233 women 20–60 years of age with recurrent depression who were seeking nonpharmacologic management of their recurrent illness were enrolled in the study between September 1992 and April 1999; we expected that approximately 100 participants would achieve a sustained remission with interpersonal psychotherapy alone in the acute treatment phase and continue on to the maintenance phase. Each participant received a complete description of the study and provided written informed consent in accordance with procedures approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Pittsburgh. In the study description, participants were advised that if IPT alone was not successful in bringing about a remission of their depression, they would be offered the option of having pharmacotherapy added to their acute treatment, and after 5 months of stable remission the pharmacotherapy would be withdrawn for the maintenance phase.

To be included in the study, patients had to be experiencing at least their second episode of unipolar depression according to Research Diagnostic Criteria (18) as extracted from either the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia (18) or the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (19), and the immediately preceding episode had to be 10–130 weeks before the onset of the index episode. Other inclusion criteria were age between 20 and 60 years; score ≥ 15 on the 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D) (20); and score ≥7 on the Raskin Severity of Depression Scale (21). Exclusion criteria were presence of comorbid axis I disorders (other than anxiety disorders, hypomania, adult-onset dysthymia, and eating disorder not otherwise specified), full-criteria antisocial or borderline personality disorder, history of substance abuse or dependence within the past 2 years, history of a manic episode, or any medical condition (excluding pregnancy) incompatible with the use of a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI).

STUDY DESIGN

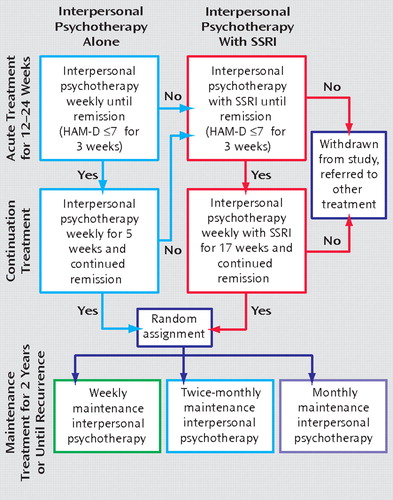

Figure 1 provides an outline of the study design. Participants entered a 12- to 24-weeks acute treatment phase in which they were treated with weekly IPT until remission, which was defined as 3 consecutive weeks with a HAM-D score ≤7. If, after the first 4 weeks and four IPT sessions, the HAM-D score was not reduced by at least 33%, the frequency of IPT sessions was increased to twice weekly for 4 weeks. After a minimum of 12 weeks in this acute phase, those who were able to sustain remission for 5 additional weeks were then randomly assigned to weekly, twice-monthly, or monthly maintenance IPT sessions for a period of 2 years.

Figure 1. Study Design for Randomized Trial of Weekly, Twice-Monthly, and Monthly Interpersonal Psychotherapy as Maintenance Treatment for Women With Recurrent Depressiona

a HAM-D = Hamilton Depression Rating Scale.

Participants who did not respond to weekly sessions of IPT alone during acute treatment were offered the option of having pharmacotherapy with an SSRI added to their treatment regimen. Nonresponse was defined as any one of the following: a reduction of <25% from baseline in the HAM-D score by week 6; a reduction of <50% after 4 weeks of weekly IPT followed by 4 weeks of twice-weekly IPT; a reduction of <50% by week 12; or absence of remission after 24 weeks of IPT alone. Those who agreed to the addition of pharmacotherapy were treated with an SSRI and ongoing weekly IPT. Pharmacotherapy typically began with 10–20 mg/day of fluoxetine.

After initial remission of symptoms (HAM-D score ≤7 for 3 weeks), participants who required the addition of medication then entered a continuation phase that lasted an additional 17 weeks. Because our goal was to study various “doses” of IPT alone as a maintenance treatment, and because our participants had entered the study with the hope of being treated and maintained recurrence-free without medication, we attempted discontinuation of the SSRI at the end of the continuation phase over a period of 1 to 4 weeks. The SSRI was discontinued only after a careful discussion of the potential risks of discontinuing medication and with careful monitoring of patients. These participants then continued to receive IPT alone for 4–6 weeks to ensure that their remission was stable before they entered the experimental maintenance phase.

At the end of the continuation phase, all participants were randomly assigned to weekly, twice-monthly, or monthly maintenance IPT sessions for a period of 2 years or until recurrence (see Figure 2).Recurrence was defined as a reemergence of symptoms meeting DSM-IV criteria for major depression, confirmed by a senior psychiatrist who was not part of the investigative team.

Figure 2. Flow of Patients in Randomized Trial of Weekly, Twice-Monthly, and Monthly Interpersonal Psychotherapy (IPT) as Maintenance Treatment for 233 Women With Recurrent Depression

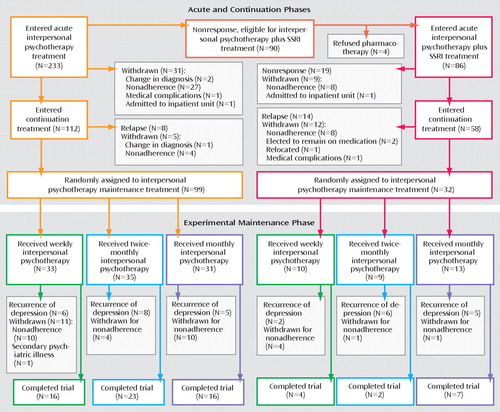

PARTICIPANTS WHO REMITTED WITH IPT ALONE

As shown in Figure 2, 31 of the initial 233 participants (13.3%) were withdrawn from treatment before the end of the acute phase, 90 (38.6%) did not respond sufficiently to IPT alone, and 112 (48%) participants who were treated with IPT alone met remission criteria and entered the continuation treatment phase, during which they continued to receive weekly IPT. If participants experienced a reemergence of their symptoms to the extent that they met criteria for major depression during the continuation phase, they were considered to have relapsed, were withdrawn from the study, and were offered appropriate alternative treatment. Eight (7%) patients experienced a relapse, five (4.5%) were withdrawn for other reasons, and the 99 (88%) who completed continuation treatment (42% of the initial sample) entered the experimental maintenance phase and were assigned to weekly (N = 33), twice-monthly (N = 35), or monthly (N = 31) maintenance IPT.

PARTICIPANTS WHO REQUIRED COMBINED ACUTE TREATMENT

Of the 90 patients who did not respond sufficiently to IPT alone, 86 consented to receive the combination of IPT and an antidepressant; of these, 58 (67.4%) remitted and entered continuation treatment, nine (10.5%) withdrew after medication was initiated, and 19 (22.0%) did not remit. Of those, who entered continuation treatment, 32 (55.2%) completed this phase and were able to discontinue medication and enter the maintenance phase without relapsing. These 32 participants (37.2% of the original sequentially treated sample of 86) were randomly assigned to weekly (N = 10), twice-monthly (N = 9), or monthly (N = 13) maintenance IPT.

DATA ANALYSIS

An intent-to-treat approach was used with all outcome measures. The attrition rate and the proportion of participants who completed the study without a recurrence were compared across the three maintenance treatment conditions using the chi-square test. Time to recurrence was estimated with Kaplan-Meier survival analysis, and the equality of the survival distribution for the three groups was tested using the log-rank test (22). Cox regression was used to analyze the association of age, number of episodes, and duration of index episode with time to recurrence.

RESULTS

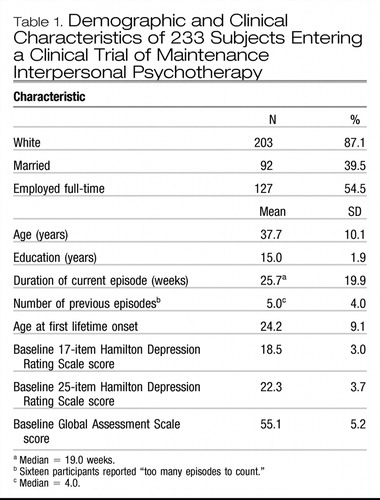

The participants' demographic and clinical characteristics are summarized in Table 1. On average, these women had recurrent unipolar depression of moderate severity, impaired overall functioning, and a relatively early illness onset.

|

Table 1. Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of 233 Subjects Entering a Clinical Trial of Maintenance Interpersonal Psychotherapy

PARTICIPANTS WHO REMITTED WITH IPT ALONE

Among the 99 participants who were treated acutely with IPT alone and reached the maintenance phase of the study, 25 were withdrawn from the study before the end of the maintenance phase, 19 experienced a recurrence, and 55 completed 2 years of maintenance treatment without a syndromal recurrence. Thus, 19 (26%) of the 74 who remained in the study had a recurrence of depression (95% confidence interval [CI] = 16–36). The mean length of study survival for participants whose depression recurred was 36 weeks after randomized assignment. The mean recurrence-free survival time for the entire sample was 84 weeks in this 104-week trial. Survival analysis of time to recurrence by treatment frequency showed no effect of treatment frequency on recurrence-free survival.

Attrition tended to be lower among participants assigned to the twice-monthly condition (weekly: 11 of 33 [33.3%; 95% CI = 17.2–49.4]; twice-monthly: 4 of 35 [11.4%; 95% CI = 0.9–21.9]; monthly: 10 of 31 [32.3%; 95% CI = 15.8–48.8]; χ2 = 5.49, df = 2, p = 0.06). The 25 participants who withdrew during the maintenance phase did so while in a state of remission. Among those who withdrew, the mean HAM-D score at the time of withdrawal was 2.6 (SD = 5.6) for those receiving weekly IPT, 4.0 (SD = 3.7) for those receiving twice-monthly IPT, and 2.5 (SD = 2.6) for those receiving monthly IPT.

When the recurrence rate was examined over time, we noted that the majority of recurrences (79%) were during the first year of maintenance treatment: seven were during the first 6 months, eight between 6 and 12 months, two between 12 and 18 months, and two between 18 and 24 months.

PARTICIPANTS WHO REQUIRED COMBINED ACUTE TREATMENT

Among participants who required pharmacological intervention in addition to IPT to achieve remission, 32 (37%) members of the initial eligible sample entered the maintenance phase. Of these, 13 (40.6%) completed the 2-year maintenance phase without a recurrence, six (18.7%) were withdrawn from the study, and 13 experienced a recurrence. Thus, the recurrence rate among those who completed the study was 50% (95% CI = 23.4–57.4). Survival analysis of time to recurrence across the three treatment frequency conditions again showed no significant differences among the conditions.

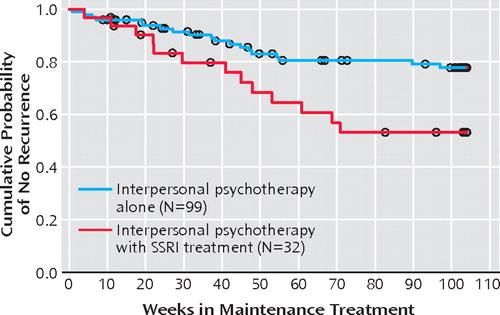

COMPARISON OF THE TWO SUBSAMPLES

When we compared the group that required only IPT to achieve remission (N = 99) and the group that required IPT plus an SSRI (N = 32) to achieve remission, we found no significant differences in baseline demographic or clinical features. A survival analysis was conducted on the combined sample, including the 99 monotherapy subjects and the 32 sequential treatment subjects (Figure 3).Kaplan-Meier estimates of time to recurrence were obtained for the two groups (IPT alone and IPT plus an SSRI), for the three frequencies of IPT sessions, and for the six groups (acute treatment requirement by maintenance treatment frequency). The comparison of the proportions surviving and survival time during maintenance treatment revealed more recurrences (χ2 = 6.02, df = 1, p < 0.02) and shorter time to recurrence (log-rank χ2 = 6.30, df = 1, p < 0.02) in the sequential treatment sample. The mean time to recurrence was 56.0 weeks (SE [estimate] = 4.1) for the sequential acute treatment group, in contrast to 84.0 weeks (SE [estimate] = 2.9) for the acute IPT monotherapy sample. The log-rank test for the frequency of IPT sessions was not significant. A Cox regression model showed that age, number of episodes, and duration of the index episode were not associated with time to recurrence. The dichotomous variable IPT alone versus IPT plus an SSRI maintained its significant effect, and the frequency of IPT sessions remained nonsignificant.

Figure 3. Survival Curves of Time to Recurrence During Maintenance Treatment With Interpersonal Psychotherapy, by Acute Treatment Modalitya

a Estimated with Kaplan-Meier survival analysis. For women who needed an SSRI in addition to interpersonal psychotherapy to achieve remission during the acute phase, time to recurrence was shorter than for those who remitted with interpersonal therapy alone (χ2 = 6.30, df = 1, p < 0.02). Censored observations are represented by open circles.

DISCUSSION

We studied IPT as an acute and a maintenance treatment for women with recurrent depression. Our results lead to three conclusions: 1) when IPT alone is effective in bringing about a remission of symptoms, it is also effective as a maintenance treatment; 2) in the maintenance phase, IPT delivered at weekly or twice-monthly intervals is no more effective in maintaining remission than IPT delivered on a monthly basis; and 3) when IPT alone is not effective in the acute treatment phase, it is generally not effective in maintaining remission. Thus, for women who require combined treatment to achieve remission, IPT alone cannot be recommended as a maintenance treatment.

Among participants who remitted with IPT alone during acute treatment and remained in the trial, we observed a recurrence rate of only 26% over a 24-month period of maintenance treatment with IPT alone. This rate is among the lowest observed to date in maintenance treatment studies involving patients with established histories of recurrence (4, 10, 13, 23, 24). Furthermore, those who remained in the trial for the full 2 years were generally in complete remission throughout that period (mean HAM-D score over 2 years = 3.05 [SD = 1.81]). In our previous maintenance study (10), in which patients were treated acutely with a combination of pharmacotherapy and IPT, only those who received an antidepressant in the maintenance phase approached this level of prophylaxis. However, in that trial, we noted that a subset of patients treated with maintenance IPT alone achieved a high level of protection. This subset was characterized by a course of maintenance IPT that was consistently focused on the interpersonal themes that are central to IPT (25). Among those who achieve remission with IPT alone, perhaps one characteristic of patient/therapist dyads is their ability (either inherent in the dyad or learned during acute treatment) to remain focused on interpersonal themes during the therapy sessions. This hypothesis is supported by analyses (26, 27) demonstrating that subjects who did not do well in the acute phase of this trial tended to have higher levels of somatic anxiety symptoms, somatic complaints, and preoccupation with somatic changes—features likely to have interfered with their ability to focus on interpersonal themes during their therapy sessions. Thus, the ability to achieve stable remission with IPT alone may have selected the subpopulation uniquely able to remain focused on interpersonal themes and benefit from this specific treatment.

To our surprise, we found no difference in prophylactic efficacy among the three frequencies of maintenance IPT we studied. We did, however, observe clear differences in the risk of recurrence in those participants who achieved remission with IPT alone as compared with those who required the addition of pharmacotherapy. Indeed, the subgroup that required the addition of an SSRI to achieve a sustained remission had a markedly different clinical course throughout the trial. Although the remission rate for the group that received psychotherapy plus an SSRI was reasonably good, the continuation treatment phase was not benign for these subjects; 29% experienced a relapse, including 15% who relapsed while receiving combined treatment. Four additional relapses occurred in the transition to maintenance treatment with IPT alone, either during the process of medication discontinuation or shortly thereafter. This points to the potential difficulty of discontinuing medication after successful resolution of acute symptoms in patients who require the addition of pharmacotherapy to ongoing psychotherapy. At the time the study was conducted, and considering the strong preference of many women in their childbearing years for nonpharmacologic treatment, the attempt to withdraw medication after 5 months of stable remission seemed reasonable; however, this report now adds to the accumulating data supporting the necessity of pharmacologic maintenance treatment in individuals who require pharmacotherapy to achieve remission. Given the small number of participants in this subgroup who were able to enter the maintenance phase and the low likelihood that many clinicians today would elect to provide nonpharmacologic maintenance treatment alone to women who needed combination treatment to achieve remission, generalization from this subsample about the value of various frequencies of IPT is probably not meaningful.

Although no statistically significant differences were found in baseline HAM-D scores or number of previous episodes, it seems likely that participants in the group needing sequential treatment had some biological difference from the other group that is not reflected in the measures we employed. As we reported earlier (26, 27), subjects whose depression was complicated by panic-like symptoms or a panic spectrum disorder had a more problematic acute treatment course; however, these features are not captured by total scores on traditional measures of depression severity.

A major limitation of the design of this study is that it did not include a no-treatment comparison condition in the maintenance phase. Having observed high rates of recurrence among subjects assigned to brief “medication clinic” visits with placebo in our original maintenance trials, we felt a no-treatment control condition would not be ethical in this study.

The literature on maintenance treatment increasingly indicates that if a patient gets well (not merely better, but well) on any given treatment, the prudent maintenance strategy is to continue that treatment. For medication, it seems that this needs to be done at the full dose that was used to achieve remission. For psychotherapy, in contrast, the continuation and maintenance studies completed to date suggest that relatively infrequent contact, in the form of either booster sessions or monthly treatment sessions, may be sufficient to protect the majority of individuals who are able to achieve remission with psychotherapy alone in the subsequent 1 to 2 years. Thus, session frequency may represent a limited analogy to the concept of medication dose. Other factors, such as fidelity to the therapeutic model and therapeutic intensity, which are not captured by visit frequency, may be more important for protection against recurrence.

While it is clear in retrospect that a subgroup of the women we studied was well served in both acute and maintenance treatment by a depression-specific psychotherapy, none of the traditional measures of severity or other parameters of illness distinguished that subgroup from those who required the combination therapy to achieve remission and, in many cases, to maintain that remission. The field clearly needs new ways of distinguishing the various phenotypes of unipolar disorder for which treatment requirements differ. This need is likely to be met only if we develop new and more subtle means of characterizing patients than our current measures of depression severity provide.

1 Koran LM, Gelenberg AJ, Kornstein SG, Howland RH, Friedman RA, DeBattista C, Klein D, Kocsis JH, Schatzberg AF, Thase ME, Rush AJ, Hirschfield RMA, LaVange LM, Keller MB: Sertraline versus imipramine to prevent relapse in chronic depression. J Affect Disord 2001; 65: 27– 36Crossref, Google Scholar

2 Bump GM, Mulsant BH, Pollock BG, Mazumdar S, Begley AE, Dew MA, Reynolds CF: Paroxetine versus nortriptyline in the continuation and maintenance treatment of depression in the elderly. Depress Anxiety 2001; 13: 38– 44Crossref, Google Scholar

3 Hochstrasser B, Isaksen PM, Koponen H, Lauritzen L, Mahnert FA, Rouillon F, Wade AG, Andersen M, Pedersen SF, De Swart JCG, Nil R: Prophylactic effect of citalopram in unipolar, recurrent depression: placebo-controlled study of maintenance therapy. Br J Psychiatry 2001; 178: 304– 310Crossref, Google Scholar

4 Prien RF, Kupfer DJ, Mansky PA, Small JG, Tuason VB, Voss CB, Johnson WE: Drug therapy in the prevention of recurrences in unipolar and bipolar affective disorders: report of the NIMH Collaborative Study Group comparing lithium carbonate, imipramine, and a lithium carbonate-imipramine combination. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1984; 41: 1096– 1104Crossref, Google Scholar

5 Garland A, Scott J: Cognitive therapy for depression in women. Psychiatr Ann 2002; 32: 465– 476Crossref, Google Scholar

6 Weissman MM: The paradox of psychotherapy, in Treatment of Depression: Bridging the 21st Century. Edited by Weissman MM. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 2001, pp 301– 329Google Scholar

7 Jarrett RB, Kraft D, Doyle J, Foster BM, Eaves GG, Silver PC: Preventing recurrent depression using cognitive therapy with and without a continuation phase: a randomized clinical trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2001; 58: 381– 388Crossref, Google Scholar

8 Hollon SD, Shelton RC, Salomon R, Lovett M: Prevention of Relapse. Abstract 85C in 2002 Annual Meeting Syllabus and Proceedings Summary. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 2002Google Scholar

9 Beck AT, Rush J, Shaw BF, Emery G: Cognitive Therapy of Depression: A Treatment Manual. New York, Guilford, 1979Google Scholar

10 Frank E, Kupfer DJ, Perel MJ, Cornes CL, Jarrett DB, Mallinger AG, Thase ME, McEachran AB, Grochocinski VJ: Three-year outcomes for maintenance therapies in recurrent depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1990; 47: 1093– 1099Crossref, Google Scholar

11 Klerman GL, Weissman MM, Rounsaville BJ, Chevron ES: Interpersonal Psychotherapy of Depression. New York, Basic Books, 1984Google Scholar

12 Frank E: Interpersonal psychotherapy as a maintenance treatment for patients with recurrent depression. Psychotherapy 1991; 28: 259– 266Crossref, Google Scholar

13 Reynolds CF, Frank E, Perel JM, Imber SD, Cornes C, Miller MD, Mazumdar S, Houck PR, Dew MA, Stack JA, Pollock BG, Kupfer DJ: Three-year outcomes of maintenance therapies for recurrent major depression in old age: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized trial of nortriptyline and interpersonal psychotherapy. JAMA 1999; 281: 39– 45Crossref, Google Scholar

14 Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Swartz M, Blazer DG, Nelson CB: Sex and depression in the National Comorbidity Survey, I: lifetime prevalence, chronicity, and recurrence. J Affect Disord 1993; 29: 85– 96Crossref, Google Scholar

15 Weissman MM, Leaf PJ, Holzer CE III, Myers JK, Tischler GL: The epidemiology of depression: an update of sex differences in rates. J Affect Disord 1984; 7: 179– 188Crossref, Google Scholar

16 Weissman MM, Klerman GL: Gender and depression. Trends Neurosci 1985; 8: 416– 420Crossref, Google Scholar

17 Brown GW: Life events, psychiatric disorder, and physical illness. J Psychosom Res 1981; 25: 461– 473Crossref, Google Scholar

18 Spitzer RL, Endicott J: Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia—Lifetime Version. New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research, 1978Google Scholar

19 First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders, Patient Edition (SCIDP), version 2. New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research, 1995Google Scholar

20 Hamilton M: A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1960; 23: 56– 62Crossref, Google Scholar

21 Raskin A: Three-area severity of depression scale, in Dictionary of Behavioral Assessment Techniques. Edited by Bellack AS, Herson M. New York, Pergamon, 1988Google Scholar

22 Kalbfleish JD, Prentice RL: The Statistical Analysis of Failure Time Data. New York, Wiley, 1980Google Scholar

23 Geddes J, Carney S, Davies C, Furukawa T, Kupfer D, Frank E, Goodwin G: Relapse prevention with antidepressant drug treatment in depressive disorders: a systematic review. Lancet 2003; 361: 653– 661Crossref, Google Scholar

24 McGrath PJ, Stewart JW, Quitkin FM, Chen Y, Alpert JE, Nierenberg AA, Fava M, Cheng J, Petkova E: Predictors of relapse in a prospective study of fluoxetine treatment of major depression. Am J Psychiatry 2006; 163: 1542– 1548Crossref, Google Scholar

25 Frank E, Kupfer DJ, Wagner EF, McEachran A, Cornes C: Efficacy of interpersonal psychotherapy as a maintenance treatment for recurrent depression: contributing factors. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1991; 48: 1053– 1059Crossref, Google Scholar

26 Feske U, Frank E, Kupfer DJ, Shear MK, Weaver E: Anxiety as a predictor of response to interpersonal psychotherapy for recurrent major depression: an exploratory investigation. Depress Anxiety 1998; 8: 135– 141Crossref, Google Scholar

27 Frank E, Shear MK, Rucci P, Cyranowski JM, Endicott J, Fagiolini A, Grochocinski VJ, Houck P, Kupfer DJ, Maser JD, Cassano GB: Influence of panic-agoraphobic spectrum symptoms on treatment response in patients with recurrent major depression. Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157: 1101– 1107Crossref, Google Scholar