A Review of Antipsychotics in the Treatment of Obsessive Compulsive Disorder

Abstract

(Reprinted with permission from the Journal of Psychopharmacology 2006; 20(1):97–103)

RATIONALE

Although many individuals with obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) show significant improvement after treatment with serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SRIs), the treatment effect is usually partial and residual symptoms remain in most cases despite continued treatment. The proportion of patients failing to achieve a satisfactory outcome is difficult to define, but may be estimated at approximately 40% of cases. Even after switching to a second SRI, approximately 30% of cases do not respond (March et al., 1997). While there is a wealth of empirical data supporting first-line treatment of OCD, the evidence-base for second-line treatments is slim. In this paper we review current evidence for co-administration of antipsychotics in SRI-resistant cases of OCD, based upon, wherever possible, randomized controlled trials (RCTs). Uncontrolled studies are cited where systematic data are lacking (so far there have been no meta-analyses of treatment studies for this subgroup). A systematic search of electronic databases (EMBase [1974-date], MEDLINE [1966-date], PsychInfo [1987-date]) was run using combinations of the terms obsessive compulsive and (randomized or control or clinical trial or placebo or blind) or (systematic or review or meta-analysis), as well as individual drug names. This was complemented by consulting with colleagues in the field and reviewing recent unpublished data presented at international, peer-reviewed symposia. Most published studies have investigated acute treatment of OCD, with a shortage of data relating to the treatment-resistant condition. Previous reviews of this area (e.g., Sareen et al., 2004) have been superceded by the publication of several new studies within the last 12 months.

PREDICTING TREATMENT-RESPONSE WITH SRIS

Previous studies of SRI response predictors are few in number and inconsistent in their findings. Mataix-Cols et al. (1999) suggest that adults with compulsive rituals, early-onset, longer illness duration, chronic course and presence of comorbid tics and personality disorders (specifically schizotypal) do not respond well. Further analyses of clomipramine and fluoxetine data suggest a more favourable response for patients who were previously SRI-naïve and a less favourable response for individuals with sub-clinical depressive symptoms. Early age of onset predicted a poor response to clomipramine, but not to fluoxetine (Ackerman and Greenland, 2002). More recently, analysis of a large citalopram database suggests that patients with long illness durations, previous SRI treatment and greater illness severity are more likely to be treatment resistant (Stein et al., 2001). Finally, one small study has identified a better response in females (Mundo et al., 1999) while Geller et al. (2003) showed that children with comorbid attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, tic disorder and oppositional defiant disorder did not respond well.

DEFINITIONS OF TREATMENT-RESPONSE AND TREATMENT-FAILURE

Research on treatment-resistant OCD is marred by a lack of standardized criteria for treatment-response and failure, making it difficult to draw general conclusions from previously published work. For example, some studies report on extreme refractory cases who had failed to respond to successive treatments with different SRIs, whereas others included partial responders to a single SRI. Criteria based on expert consensus of opinion have been proposed by Pallanti et al. (2002a) who suggest that ≥35% improvements in baseline Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS) total scores, or a classification of ‘much’ or ‘very much improved’ on the CGI-I, represent meaningful clinical responses, while ‘remission’ should require a total Y-BOCS score of under 16. A 25–35% improvement in Y-BOCS scores suggests partial response. Relapse was defined as a 25% worsening in Y-BOCS (or a CGI-I score of 6), after a period of remission, and the term ‘treatment-refractory’ was reserved for those who did not respond to ‘all available treatments’. Levels of non-response, according to the numbers of failed treatments, were also defined. It remains to be seen whether these criteria will be universally accepted by the scientific community.

FIRST-GENERATION ANTIPSYCHOTICS IN RESISTANT OCD

Early studies of antipsychotic monotherapy do not meet today's clinical trial standards and these agents are not recognized as treatments for OCD. One placebo-controlled trial of chlorpromazine in 75 ill-defined cases failed to show a specific effect on obsessive-compulsive symptoms (Trethowan and Scott, 1955). Several subsequent positive case reports showed antiobsessional effects of monotherapy with a variety of antipsychotics (Altschuler, 1962; Hussain and Ahad, 1970; O'Regan, 1970; Rivers-Bulkeley and Hollender, 1982) but these were mainly in schizophrenic patients.

In contrast, first generation antipsychotics showed promise as adjunctive treatments given with SRIs in resistant cases. McDougle et al. (1990) added open-label pimozide (6.5 mg) in 17 patients who had not responded to fluvoxamine and reported some benefit, especially for individuals with comorbid chronic tics or schizotypal disorder. A subsequent double-blind placebo-controlled study by the same authors showed significant Y-BOCS improvement for low-dose haloperidol (2 mg) added to fluvoxamine. Mean Y-BOCS reduction from baseline on haloperidol was 26%, and 11/17 (64%) patients receiving haloperidol achieved ‘responder’ status (35% improvement in baseline Y-BOCS to below 16; CGI-I score ≤2 and consensus improvement) by as early as 4 weeks, compared to none on placebo. Once more, a stronger response was observed in patients with comorbid tics (McDougle et al., 1994). Antipsychotics such as haloperidol and sulpiride are first-line treatments for Tourette Syndrome, so this finding supports a theoretical link between these disorders. The combination of first-generation antipsychotics and SRIs increases the side-effect burden, including extra-pyramidal effects. Treatment should therefore begin with very low doses, increased cautiously subject to tolerability (e.g., 0.25–0.5 mg haloperidol, titrated slowly to 2–4 mg: McDougle and Walsh, 2001).

SECOND GENERATION ANTIPSYCHOTICS IN OCD

Second generation antipsychotics which affect serotonin and dopamine neurotransmission offer promise as combination treatments with SRIs and have lesser side effect profiles.

RISPERIDONE

Reports of improvements in most cases treated with adjunctive risperidone in four open case studies (McDougle et al., 1995a; Saxena et al., 1996; Stein et al., 1997; Pfanner et al., 2000) were followed up by McDougle et al. (2000) who reported the first double-blind, placebo-controlled study of risperidone augmentation in 36 patients unresponsive to 12 weeks treatment on an SRI. In their completer analysis of 33 patients, risperidone (2.2 mg) was superior to placebo in reducing Y-BOCS scores (mean post-baseline improvement of 31.8%) as well as anxiety and depressive symptoms and was well-tolerated. Of the risperidone completers, 9/18 (50%) were considered ‘marked responders’ (using the same criteria as the haloperidol study) or ‘partial responders’ (2 out of the 3 marked responder criteria), compared to none treated with placebo. There was no difference between those with and without comorbid tics or schizotypy. However, those who had two or more SRIs were less likely to respond to risperidone addition than those who had failed to respond to only one. A smaller double-blind study by Hollander et al. (2003a) examined patients failing to respond to at least 2 trials of SRIs using an intent-to-treat analysis. Four of ten (40%) randomized to risperidone (0.5–3 mg) were responders (CGI-I ≤ 2 and baseline Y-BOCS decrease of ≥25%) at the 8-week end-point, compared with none of the six patients randomized to placebo. However, the mean reduction in baseline Y-BOCS scores was only 19% and the difference was not significant, possibly owing to a small sample size. Less impaired insight at entry predicted a better response with risperidone, perhaps reflecting less severe illness. A third trial (Erzegovesi et al., 2005) enrolled 45 drug-naïve subjects in a 12-week open label fluvoxamine phase, after which ten treatment-non responders (Y-BOCS reduction <35% and CGI-I > 2) were randomized to 6 weeks low dose (0.5 mg) risperidone and ten to placebo augmentation. The study did not report a between group analysis, but five risperidone-treated cases responded (≥35% YBOCS improvement) compared to two on placebo.

QUETIAPINE

Quetiapine, as an add-on to SRIs, has also been the subject of recent investigation. Contradictory results were obtained from open label studies, most of which showed benefits in up to 50% individuals treated (Denys et al., 2002; Sevincok and Topuz, 2003; Bogan et al., 2005) although another study showed little benefit (Mohr et al., 2002). The single-blind study by Atmaca et al. (2002) found a clinical response in 14/27 (64%) cases.

Three double-blind, placebo-controlled studies of quetiapine have been recently completed and these also show contradictory results. In the first (Fineberg et al., 2005) 21 patients with DSM-IV OCD without significant Axis I comorbidity, and who had failed to respond to at least 6 months SRI treatment, were treated for 16 weeks with SRI and quetiapine (≤400 mg) or SRI and placebo. Quetiapine was well tolerated with just one participant in each group dropping out. The quetiapine group's reduction in baseline Y-BOCS scores averaged 14% at week 16 compared to 6% under placebo. Considerable variation in treatment-response to quetiapine was seen, with most patients responding at the placebo-level. However 3/11 of the quetiapine group showed at least a partial treatment-response by Pallanti et al.'s (2002a) criteria, compared to just 1/10 under placebo. There was no relationship between treatment response and Yale Tic Severity Scale, Y-BOCS or MÅDRS scores, or previous length of illness or number/duration of failed treatments. Although the sample size was relatively small the study was powered at 90% to detect as significant a 4 point difference on the Y-BOCS.

In the study by Carey et al. (2005) 42 subjects who had responded inadequately (Y-BOCS reduction < 25% or CGI-I >2) to open-label treatment with an SRI for 12 weeks were randomized to either placebo or flexible doses of quetiapine for 6 weeks. It is noteworthy that cases received only 6 weeks treatment at maximum tolerated dose or manufacturers recommended maximum dose, which may have been too short to discriminate SRI resistance. Quetiapine was generally well tolerated and there was significant improvement from baseline to endpoint on the Y-BOCS in both the quetiapine and placebo groups (quetiapine, n = 20, p < 0.0001; placebo, n = 21, p = 0.001) with 40% (n = 8) of quetiapine and 47.6% (n = 10) of placebo treated individuals being classified as responders. Quetiapine did not demonstrate a significant benefit over placebo at the end of the 6-week treatment period. Similarly quetiapine failed to separate from placebo in the subgroup of subjects (n = 10) with co-morbid tics. The failure to demonstrate an advantage for the active drug has been attributed to the inclusion of cases of unstable OCD or partially SRI-resistant individuals who went on to respond further to extended treatment with the SRI.

By contrast, another double-blind, placebo-controlled study (Denys et al., 2004a) has shown significant efficacy for quetiapine (<300 mg) augmentation in a sample of 40 patients who had previously failed to respond to at least two SRIs. An intent-to-treat analysis for the 20 quetiapine-treated cases showed a significant advantage over placebo from 4 weeks on the Y-BOCS and a mean decrease of 31% on baseline Y-BOCS, compared to 6% in the placebo group at the 8-week endpoint. Decreases in Y-BOCS scores correlated positively with severity of obsessions at entry. Eight out of 20 (40%) quetiapine patients showed meaningful clinical responses by Pallanti et al.'s (2002a) criteria compared to just 2/20 (10%) under placebo.

OLANZAPINE

The potentially encouraging results of open-label olanzapine studies (Weiss et al., 1999; Bogetto et al., 2000; Koran et al., 2000; Francobandiera, 2001; Crocq et al., 2002; D'Amico et al., 2003) were not supported by a double-blind, placebo-controlled study run by Shapira et al. (2004). This study included 44 partial-or non-responders to 8 weeks open-label fluoxetine; both the fluoxetine plus olanzapine (5–10 mg), and fluoxetine plus placebo groups improved over a 6-week study period, and there was no additional advantage for olanzapine augmentation. Nine of 22 (41%) showed at least a 25% post-baseline reduction in Y-BOCS scores in both the olanzapine and placebo groups. Differences in entry criteria between this study, which included ‘partial responders’ and which used short (8-week) pre-trial SRI treatment, and other studies that included more stable, treatment-refractory cases, may partly explain the differences in the results.

By contrast, Bystritsky et al. (2004) recruited a more treatment-refractory group of 26 OCD patients who had been unresponsive to at least two 12-week trials of SRIs and one trial of behaviour therapy. Eleven of 13 olanzapine treated patients (mean dose 11.2 mg) and seven of 13 placebo treated patients completed the study. Olanzapine was well-tolerated and, by intent-to-treat analysis, was significantly superior to placebo at the 6-week endpoint. The mean reduction of baseline Y-BOCS scores was just 16% but the placebo-group showed no improvement at all with only seven completing the study. Six (46%) of the olanzapine group were responders (25% improvement on Y-BOCS). Because of the high placebo dropout rate, the authors also ran a completer analysis which failed to reach significance so a larger study was recommended. Given the inconsistency of the data collected so far, the efficacy of olanzapine for treatment resistant OCD remains equivocal.

OTHER ANTIPSYCHOTIC AGENTS

A single positive open-label study of the more selective dopamine antagonist amisulpride (200–600 mg) used as an adjunct to SRI in 20 cases of resistant OCD (Metin et al., 2003) merits replication under controlled conditions. However, the results for clozapine, given as a monotherapy to 12 adults with resistant OCD in an open-label design showed no effect (McDougle et al., 1995b). Aripiprazole (10–30 g) was also studied as a monotherapy using an open-label design in a mixture of drug-naive and resistant cases (Connor et al., 2005). Two out of seven cases withdrew because of side effects, and there was no significant change from baseline on Y-BOCS scores for the group, although two patients were judged to be responders.

Some authors have reported emergent obsessions during treatment of schizophrenia with atypical antipsychotics, which may be related to their mixed receptor antagonist properties (Sareen et al., 2004). Obsessive-compulsive symptoms have, however, long been recognized to be common among patients with schizophrenia (Poyurovsky and Koran, 2005) and may well be linked to the schizophrenic disorder as opposed to the antipsychotic treatment.

PREDICTORS OF RESPONSE TO ANTIPSYCHOTICS IN SRI-RESISTANT OCD

The small size of all studies to date limits the extent to which we can identify predictors of antipsychotic response, though presence of comorbid tics, insightfulness and true SRI-resistance may predict a better outcome. A FDG-PET study by Buchsbaum and colleagues (2002) has investigated SRI-responsive cases before and after risperidone and was reported to have found a superior response in cases with lower metabolic activity in the striatum. This echoes the PET finding by Saxena et al. (2003) who found that lower metabolic activity in the right caudate nucleus was associated with SRI-refractoriness in untreated OCD. It also hints at a radiological endophenotype representing SRI-resistant antipsychotic responsive OCD.

SIDE EFFECTS

In the treatment-resistant OCD population, the use of first generation antipsychotics produced dose-dependent extrapyramidal side effects (EPSEs) such as akathisia to the extent that in some of the studies (e.g., McDougle, 1990) up to half the patients experienced significant impairment requiring coadministration of beta blockers and/or anticholinergics. The second generation antipsychotics appear to offer an advantage in this respect and are generally well-tolerated in the context of short-term efficacy trials. EPSEs are very uncommon in all the trials so far and dropout rates from side effects have been low. Weight gain has been reported in short-term trials of olanzapine (Bystritsy et al., 2004; Shapira et al., 2004) and drowsiness in trials of olanzapine (Bystritsky et al., 2004) and quetiapine (Fineberg et al., 2005). Longer-term studies are needed to examine this area with more confidence.

MECHANISMS OF ACTION

The mechanism by which antipsychotics might enhance SRI-mediated antiobessional activity remains speculative, owing to their different receptor-blocking profiles. Moreover, the mechanism underpinning action of even SRIs in OCD still remains unclear. While it is assumed that increased serotonergic activation in relevant brain areas, such as prefrontal cortex, thalamus and striatum play a role, the failure of acute tryptophan depletion (Barr et al., 1994) to reverse the treatment effect casts some doubt on this hypothesis, although the patients may not have been tested under optimal conditions with a challenge or an exposure strategy.

All antipsychotics found to be effective in treating OCD so far share affinity at 5HT2A, D2 and alpha 1 or 2 receptors. Some authors have considered differential blockade and activation of 5-HT2A and non 5-HT2A receptors as important (Marek et al., 2003). Second generation antipsychotics such as risperidone, olanzapine and, possibly to a lesser extent quetiapine, are distinguished by their potent antagonism at 5HT2A sites. Support for this hypothesis comes from the findings of an uncontrolled study that mirtazapine, which also antagonizes, inter-alia, 5HT2A receptors, might enhance the anti-obsessional effect of SRIs in non-resistant cases (Pallanti et al., 2004). However, the robust efficacy seen in the studies of resistant OCD with haloperidol and pimozide, which are substantially more potent at blocking dopamine than serotonin receptors, suggest a dopaminergic contribution (Denys et al., 2004b), although it should be noted that these studies included a high proportion of cases with comorbid tic disorders, which themselves respond to antipsychotic drugs. It remains unclear as to how effective these drugs might be for OCD cases without comorbid tics. Positive results from open studies of amisulpride, if confirmed in RCTs, would support a dopamine hypothesis for SRI-resistant OCD. A recent microdialysis study in rats by Denys et al. (2004c) looking at extracellular monoamines demonstrated that whereas monotherapy with either fluvoxamine or quetiapine increased striatal and prefrontal serotonin levels, only a combination of the drugs resulted in a major increase in prefrontal levels of extracellular dopamine, which they hypothesized might be necessary as well as enhanced prefrontal serotonin for treatment augmentation. Pharmacological dissection in controlled studies using more selective antagonists, such as amisulpride will be valuable. Investigation of cognitive enhancing agents such as the norepinephrine transporter inhibitor atomoxetine, which has also been reported to raise dopamine levels in prefrontal cortex but not in dependence-promoting areas such as ventral tegmental area and nucleus accumbens (Bymaster et al., 2002), may have potential for this area.

OTHER STRATEGIES IN RESISTANT OCD

Evidence for alternatives to antipsychotics as add-on treatments in OCD is sparse. Some uncontrolled case studies suggest that increasing SRI doses above formulary limits can procure a better effect (Byerly et al., 1996; Bejerot and Bodland, 1998). Intravenous clomipramine has been shown to be more effective than placebo in a single double-blind study (Fallon et al., 1998) and a positive open study of intravenous citalopram has been reported (Pallanti et al., 2002b). However, no controlled studies of the co-administration of different SRIs have been published. Positive results have, nonetheless, been reported from small, uncontrolled case series combining clomipramine with an SRI (Szegedi et al., 1996; Pallanti et al., 1999) although this strategy should be approached with caution since the pharmacokinetic interactions of these drugs at hepatic cytochrome P450 systems could be hazardous. In this respect, citalopram is least likely to interact and may be the safest SRI to combine with clomipramine (Pallanti et al., 1999). Controlled studies have confirmed the lack of efficacy of lithium augmentation in OCD (McDougle et al., 1991; Pigott et al., 1991). Similarly, double-blind placebo controlled studies have demonstrated that combination of buspirone with an SRI is not helpful (Pigott et al., 1992a; Grady et al., 1993; McDougle et al., 1993). Clonazepam as a monotherapy fails to impact on the core symptoms of OCD (Hollander et al., 2003b) though it may help with associated anxiety. Pigott et al. (1992b) reported limited efficacy for clonazepam given together with an SRI in a double-blind placebo-controlled study. Dannon et al. (2000) demonstrated efficacy for pindolol when combined with paroxetine in a double-blind placebo-controlled study, but another study combining it with fluvoxamine did not (Mundo et al., 1998). Blier and Bergeron (1996) found a beneficial effect for pindolol only when 1-tryptophan was openly added to the combination. Barr et al. (1997) investigated the addition of desipramine to SRI in a double-blind placebo-controlled study, and found no added benefit.

CONCLUSIONS

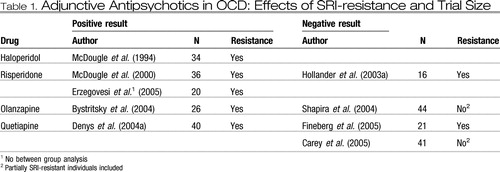

Published positive reports from placebo-controlled studies of SRI-augmentation with haloperidol, risperidone and olanzapine, and preliminary positive results on quetiapine argue persuasively for further exploration of the efficacy of this approach in resistant cases of OCD. To date, the studies have been small, and negative studies for each agent have also been reported, possibly reflecting type II error relating either to small sample sizes (Hollander et al., 2003a; Fineberg et al., 2005) or to unexpectedly high placebo response rates (Shapira et al., 2004; Carey et al., 2005) which are thought to relate to inclusion of some partially SRI-resistant cases in these two studies (Table 1). Atypical drugs appear to be better tolerated than haloperidol, but no head-to-head comparator data have yet emerged. Heterogeneity was observed within the actively treated groups, with a proportion of cases, ranging from 25–64% depending on the study, showing a clinical response to antipsychotics while others within the same treatment-group did not appear to benefit more from active drug than placebo. Identification of those likely to respond would be an extremely important development; so far, however, no consistent predictor of treatment-response has emerged. Larger collaborative studies, using of the order of 75 cases per group and including more than one active comparator, are required to refine our understanding of the role of antipsychotics in OCD-treatment.

|

Table 1. Adjunctive Antipsychotics in OCD: Effects of SRI-resistance and Trial Size

Altogether, these results favour the use of second generation antipsychotics such as risperidone and quetiapine as a first-line strategy for augmentation in resistant OCD. The results are not persuasive though for partial responders and it remains uncertain as to how long patients would need to remain on augmented treatment. A small retrospective study by Maina et al. (2003) showed that the vast majority of patients who had responded to the addition of an antipsychotic to their SRI, subsequently relapsed when the antipsychotic was withdrawn.

1 Ackerman D L, Greenland S (2002) Multivariate meta-analysis of controlled drug studies for obsessive compulsive disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol 22: 309– 317Crossref, Google Scholar

2 Altschuler M (1962) Massive doses of trifluoperazine in the treatment of compulsive rituals. Am J Psychiat 119: 367– 368Crossref, Google Scholar

3 Atmaca M, Kuloglu M, Tezcan E, Gecici O (2002) Quetiapine augmentation in patients with treatment-resistant obsessive compulsive disorder. A single blind, placebo-controlled study. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 17: 115– 119Crossref, Google Scholar

4 Barr L C, Goodman W K, Anand A, McDougle C J, Price L H (1997) Addition of desipramine to serotonin reuptake inhibitors in treatment-resistant obsessive-compulsive disorder. Am J Psychiat 154: 1293– 1295Crossref, Google Scholar

5 Barr L C, Goodman W K, McDougle C J, Delgado P L, Heninger G R, Charney D S, Price L H (1994) Tryptophan depletion in patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder who respond to serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Arch Gen Psychiat 51: 309– 317Crossref, Google Scholar

6 Bejerot S, Bodlund O (1998) Response to high doses of citalopram in treatment-resistant obsessive compulsive disorder. Acta Psychopharmacol Scandinavia 98: 423– 424Google Scholar

7 Blier P, Bergeron R (1996) Sequential administration of augmentation strategies in treatment resistant obsessive compulsive disorder: preliminary findings. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 11: 37– 44Crossref, Google Scholar

8 Bogan A M, Koran L M, Chuong H V, Vapnik T, Bystritsky A (2005) Quetiapine augmentation in obsessive compulsive disorder resistant to serotonin reuptake inhibitors: an open label study. J Clin Psychiat 66: 73– 79Crossref, Google Scholar

9 Bogetto F, Bellino S, Vaschetto P, Ziero S (2000) Olanzapine augmentation of fluvoxamine-refractory obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD): a twelve-week open trial. Psychiat Res 95: 91– 98Google Scholar

10 Buchsbaum M S, Hollander E, Pallanti S, Baldini-Rossi N, Platholi J, Bloom R, Sood E (2002) Risperidone in Refractory OCD: Positron Emission Tomography Imaging. 42nd NCDEU Meeting, Boca RatonGoogle Scholar

11 Bymaster F P, Katner J S, Nelson D L, Hemrick-Luecke S K, Threlkeld P G, Heilingstein J H, Morin S M, Gehlert D R, Perry K W (2002) Atomoxetine increases extracellular levels of norepinephrine and dopamine in prefrontal cortex of rat: a potential mechanism for efficacy in attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology 27 (5): 699– 711Google Scholar

12 Byerly M J, Goodman W K, Christenen R (1996) High doses of sertraline for treatment-resistant obsessive compulsive disorder. Am J Psychiat 153: 1232– 1233Google Scholar

13 Bystritsky A, Ackerman D L, Rosen R, Vapnik T, Gorbis E, Maidment K M, Saxena S (2004) Augmentation of SSRI response in refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder using adjunctive olanzapine: a placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Psychiat 65: 565– 568Crossref, Google Scholar

14 Carey P D, Vythilingum B, Seedat S, Muller J E, van Ameringen M, Stein D J (2005) Quetiapine augmentation of SRIs in treatment refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder: a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled study: BMC Psychiat 5 (1): 5Google Scholar

15 Connor K M, Payne V M, Gadde K M, Zhang W Davidson J R (2005) The use of aripiprazole in obsessive compulsive disorder: preliminary observations in 8 patients. J Clin Psychiat 66 (1): 49– 51Google Scholar

16 Crocq M A, Leclercq P, Guillon M S, Bailey P E (2002) Open-label olanzapine in obsessive compulsive disorder refractory to antidepressant treatment. Eur Psychiat 17: 296– 297Crossref, Google Scholar

17 D'Amico G, Cedro C, Muscatello M R, Pandolfo G, Di Rosa A E, Zoccali R, La Torre D, D'Amigo C, Spina E (2003) Olanzapine augmentation of paroxetine-refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder. Progress in Neuro-psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiat 27: 619– 623Crossref, Google Scholar

18 Dannon P N, Sasson Y, Hirschmann S, Iancu I, Grunhaus L J, Zohar J (2000) Pindolol augmentation in treatment-resistant obsessive compulsive disorder: a double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 10: 165– 169Google Scholar

19 Denys D, de Geus F, van Megen H J G M, Westenberg H G M (2004a) A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of quetiapine addition in patients with obsessive compulsive disorder refractory to serotonin reuptake inhibitors. J Clin Psych 65: 1040– 1048Google Scholar

20 Denys D, Klompmakers A A, Westenberg H G (2004c) Synergistic dopamine increase in the rat prefrontal cortex with the combination of quetiapine and fluvoxamine. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 176 (2): 195– 203Google Scholar

21 Denys D, van der Wee N, Janssen J, De Geus F, Westenberg H G (2004b) Low level of dopaminergic D2 receptor binding in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Biol Psychiat 55: 1041– 1045Crossref, Google Scholar

22 Denys D, van Megen H, Westenberg H (2002) Quetiapine addition to serotonin reuptake inhibitor treatment in patients with treatment refractory obsessive compulsive disorder: an open label study. J Clin Psychiat 63: 700– 703Crossref, Google Scholar

23 Erzegovesi S, Guglielmo E, Siliprandi F, Bellodi L (2005) Low-dose risperidone augmentation of fluvoxamine treatment for obsessive compulsive disorder: a double-blind placebo-controlled study. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 15 (1): 69– 74Google Scholar

24 Fallon B A, Liebowitz M R, Campeas R, Schneier F R, Marshall R, Davies S, Goetz D, Klein D F (1998) Intravenous clomipramine for obsessive-compulsive disorder refractory to oral clomipramine: a placebo-controlled study. Arch Gen Psychiat 55: 918– 924Crossref, Google Scholar

25 Fineberg N A, Sivakumaran T, Roberts A, Gale T (2005) Adding quetiapine to SRI in treatment-resistant obsessive compulsive disorder: a randomised controlled treatment study. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 20: 223– 226Crossref, Google Scholar

26 Francobandiera G (2001) Olanzapine augmentation of serotonin uptake inhibitors in obsessive compulsive disorder: an open study. Can J Psychiat 46: 356– 358Crossref, Google Scholar

27 Geller D A, Biederman J, Evelyn Stewart S, Mullin B, Martin A, Spencer T, Faraone S V (2003) Which SSRI? A meta-analysis of pharmacotherapy trials in paediatric obsessive compulsive disorder. Am J Psychiat 160: 1919– 1928Crossref, Google Scholar

28 Grady T A, Pigott T A, L'Heureux F, Hill J L, Berntein S E, Murphy D L (1993) Double-blind study of adjuvant buspirone for fluoxetine-treated patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Am J Psychiat 150: 819– 821Crossref, Google Scholar

29 Hollander E, Rossi N B, Sood E, Pallanti S (2003a) Risperidone augmentation in treatment-resistant obsessive compulsive disorder: a double-blind, placebo controlled study. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 6: 397– 401Crossref, Google Scholar

30 Hollander E, Kaplan A, Stahl S M (2003b) A double-blind placebo-controlled trial of clonazepam in obsessive-compulsive disorder. World J Biological Psychiat 4: 30– 34Crossref, Google Scholar

31 Hussain M Z, Ahad A (1970) Treatment of obsessive compulsive neurosis. Can Med Assoc J 103: 648Google Scholar

32 Koran L M, Ringold A L, Elliott M A (2000) Olanzapine augmentation for treatment-resistant obsessive compulsive disorder. J Clin Psychiat 61: 514– 517Crossref, Google Scholar

33 Maina G, Albert U, Ziero S, Bogetto F (2003) Antipsychotic augmentation for treatment-resistant obsessive compulsive disorder: What if antipsychotic is discontinued? Int Clin Psychopharmacol 18: 23– 28Google Scholar

34 March J S, Frances A, Kahn D A, Carpenter D (1997) The Expert Consensus Guideline Series: treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Clin Psychiat 58 (suppl.): 1– 72Google Scholar

35 Marek G J, Carpenter L L, McDougle C J, Price L H (2003) Synergistic action of 5-HT2A antagonists and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in neuropsychiatric disorders. Neuropsychopharmacol 28: 402– 412Crossref, Google Scholar

36 Mataix-Cols D, Rauch S, Manzo P A, Jenike M A, Baer L (1999) Use of factor-analysed symptom dimensions to predict outcome with serotonin reuptake inhibitors and placebo in the treatment of obsessive compulsive disorder. Am J Psychiat 156: 1409– 1416Google Scholar

37 McDougle C J, Barr L C, Goodman W K, Pelton G H, Aronson S C, Anand A, Price L H (1995b) Lack of efficacy of clozapine monotherapy in refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder. Am J Psychiat 152: 423– 429Google Scholar

38 McDougle C J, Epperson C N, Pelton G H, Wasylink S, Price L H (2000) A double-blind, placebo-controlled study of risperidone addition in serotonin reuptake inhibitor-refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder. Arch Gen Psychiat 57: 794– 801Crossref, Google Scholar

39 McDougle C J, Fleischmann R L, Epperson C N, Wayslink S, Leckmann J F, Price L H (1995a) Risperidone addition in fluvoxamine refractory obsessive compulsive disorder: three cases. J Clin Psychiat 56: 526– 528Google Scholar

40 McDougle C J, Goodman W K, Leckman J F, Holzer J C, Barr L C, McCance-Katz E (1993) Limited therapeutic effect of addition of buspirone in fluvoxamine-refractory obsessive compulsive disorder. Am J Psychiat 150: 647– 649Crossref, Google Scholar

41 McDougle C J, Goodman W K, Leckman J F, Lee N C, Heninger G R, Price L H (1994) Haloperidol addition in fluvoxamine-refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder: a double-blind placebo-controlled study in patients with and without tics. Arch Gen Psychiat 51: 302– 308Crossref, Google Scholar

42 McDougle C J, Goodman W K, Price L H, Delgado P L, Krystal J H, Charney D S, Heninger G R (1990) Neuroleptic addition in fluvoxamine-refractory obsessive compulsive disorder. Am J Psychiat 147: 652– 654Crossref, Google Scholar

43 McDougle C J, Price L H, Goodman W K, Charney D S, Heninger G R (1991) A controlled trial of lithium augmentation in fluvoxamine-refractory obsessive compulsive disorder: lack of efficacy. J Clin Psychopharmacol 11: 175– 184Google Scholar

44 McDougle C J, Walsh K H (2001) Treatment for refractory OCD. In: Fineberg N A, Marazitti D, Stein D (eds), Obsessive Compulsive Disorder; A Practical Guide. Martin Dunitz, LondonGoogle Scholar

45 Metin O, Yaziki K, Tot S, Yazici A E (2003) Amisulpride augmentation in treatment-resistant obsessive compulsive disorder: an open trial. Hum Psychopharmacol 18: 463– 467Crossref, Google Scholar

46 Mohr N, Vythilingum B, Emsley R A, Stein D J (2002) Quetiapine augmentation of serotonin reuptake inhibitors in obsessive compulsive disorder. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 17: 37– 40Crossref, Google Scholar

47 Mundo E, Bareggi S R, Pirola R, Bellodi L (1999) Effect of acute intravenous clomipramine and antiobsessional response to proserotonergic drugs: Is gender a predictive variable? Biol Psychiat 45: 290– 294Crossref, Google Scholar

48 Mundo E, Guglielmo E, Bellodi L (1998) Effect of adjuvant pindolol on the antiobsessional response to fluvoxamine; a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 13: 219– 224Crossref, Google Scholar

49 O'Regan J B (1970) Treatment of obsessive-compulsive neurosis. Can Med Assoc J 103: 650– 651Google Scholar

50 Pallanti S, Hollander E, Bienstock C, Koran L, Leckman J, Marazziti D, Pato M, Stein D, Zohar and the International Treatment-Refractory OCD Consortium (2002a) Treatment non-response in OCD: methodological issues and operational definitions. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 5: 181– 191Google Scholar

51 Pallanti S, Quercioli L, Bruscoli M (2004) Response acceleration with mirtazapine augmentation of citalopram in obsessive-compulsive disorder patients without comorbid depression: a pilot study. J Clin Psychiat 65 (10): 1394– 1399Google Scholar

52 Pallanti S, Quercioli L, Koran L M (2002b) Citalopram infusions in resistant obsessive compulsive disorder: an open trial. J Clin Psychiat 63: 796– 801Crossref, Google Scholar

53 Pallanti S, Quercioli L, Paiva R S, Koran L M (1999) Citalopram for treatment-resistant obsessive-compulsive disorder. Eur Psychiat 14: 101– 106Crossref, Google Scholar

54 Pfanner C, Marazziti D, Dell'Osso L, Presta S, Gemignani A, Milanfranchi A, Cassano G B (2000) Risperidone augmentation in refractory obsessive compulsive disorder: an open-label study. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 15: 297– 301Crossref, Google Scholar

55 Pigott T A, L'Heureux F, Hill J L, Bihari K, Bernstein S E, Murphy D L (1992a) A double-blind study of adjuvant buspirone hydrochloride in clomipramine-treated patients with obsessive compulsive disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol 12: 11– 18Google Scholar

56 Pigott T A, L'Heureux F, Rubinstein C F, Hill J L, Murphy D L (1992b) A controlled trial of clonazepam augmentation in OCD patients treated with clomipramine or fluoxetine. New Research Abstracts NR 144 presented at the 145th Annual Meeting of the American Psychiatric Association, Washington, DC, USAGoogle Scholar

57 Pigott T A, Pato M T, L'Heureux F, Hill J L, Grover G N, Bernstein S E, Murphy D L (1991) A controlled comparison of adjuvant lithium carbonate or thyroid hormone in clomipramine-treated patients with obsessive compulsive disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol 11: 242– 248Google Scholar

58 Poyurovsky M, Koran L (2005) Obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) with schizotypy vs. schizophrenia with OCD: diagnostic dilemmas and therapeutic implications. J Psychiatr Res 39 (4): 399– 408Google Scholar

59 Rivers-Bulkeley N, Hollender M H (1982) Successful treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder with loxapine. Am J Psychiat 139: 1345– 1346Crossref, Google Scholar

60 Sareen J, Kirshner A, Lander M, Kjeniested K D, Eleff M K, Reiss J P (2004) Do antipsychotics ameliorate or exacerbate obsessive compulsive disorder? A systematic review. J Affective Disorders 82: 167– 174Crossref, Google Scholar

61 Saxena S, Brody A L, Ho M L, Zohrabi N, Maidment K M, Baxter L (2003) Differential brain metabolic predictors of response to paroxetine in obsessive compulsive disorder versus major depression. Am J Psychiat 160: 522– 532Crossref, Google Scholar

62 Saxena S, Wang D, Bystritsky A, Baxter Jr L R (1996) Risperidone augmentation of SRI treatment for refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Clin Psychiat 57: 303– 306Google Scholar

63 Sevincok L, Topuz A (2003) Lack of efficacy of low dose quetiapine addition in refractory obsessive compulsive disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol 23: 448– 450Google Scholar

64 Shapira N A, Ward H E, Mandoki M, Murphy T K, Yang M C, Blier P, Goodman W K (2004) A double-blind placebo-controlled trial of olanzapine addition in fluoxetine-refractory obsessive compulsive disorder. Biol Psychiat 55: 553– 563Crossref, Google Scholar

65 Stein D J, Bouwer C, Hawkridge S, Emsley R A (1997) Risperidone augmentation of serotonin reuptake inhibitors in obsessive compulsive and related disorders. J Clin Psychiat 58: 119– 122Crossref, Google Scholar

66 Stein D, Montgomery S A, Kasper S, Tanghoj P (2001) Predictors of response to pharmacotherapy with citalopram in obsessive compulsive disorder. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 16: 357– 361Crossref, Google Scholar

67 Szegedi A, Wetzel H, Leal M, Hartter S, Hiemke C (1996) Combination treatment with clomipramine and fluvoxamine: drug monitoring, safety and tolerability data. J Clin Psychiat 57: 257– 264Google Scholar

68 Trethowan W H, Scott P A (1955) Chlorpromazine in obsessive-compulsive and allied disorders. Lancet 268: 781– 785Crossref, Google Scholar

69 Weiss E L, Potenza M N, McDougle C J, Epperson C N (1999) Olanzapine addition in obsessive compulsive disorder refractory to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors; an open-label case series. J Clin Psychiat 60: 524– 527Crossref, Google Scholar