Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder

Abstract

OCD, a surprisingly common disorder, is often hidden by patients who have insight into the inappropriateness of their obsessional concerns and the excessive rituals they feel compelled to perform to ward off exceedingly low risk danger or more vague feelings of discomfort. Onset in childhood is common and many suffer lifelong with a few becoming incapacitated by incessant demands of their disorder.

Diagnosis is straightforward once obsessions and rituals are admitted. Once recognized, treatment with cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) and potent serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SRIs) is often helpful, alone or in combination. For those with disorders unresponsive to these standard treatments, somatic treatment with multiple medications and rarely, deep brain stimulation or neurosurgical lesions may be helpful. The largest obstacle to effective treatment of OCD at present is the difficulty obtaining effective CBT which is twice as beneficial, on average, as SRIs.

History

Recognizable in centuries old writings, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) was often thought to be an affliction requiring religious intervention (1). Bishop John Moore certainly seems to have been describing obsessive-compulsive patients who

“… [Have] naughty, and sometimes Blasphemous Thoughts [which] start in their Minds, while they are exercised in the Worship of God [despite] all their endeavors to stifle and suppress them … the more they struggle with them, the more they encrease.” [Moore 1692/1982, quoted in Pitman (1, p. 4)]

Even earlier, Bishop Jeremy Taylor [1660/1982, quoted in Pitman (1, p. 4)] had referred to William of Oseny who

“read two or three books of Religion and devotion very often … [he] had read over those books 3 hours every day. In a short time he had read over the books three times more…. [He] began to think … that now he was to spend 6 hours every day in reading those books, because he had now read them over six times. He presently considered that … he must be tied to 12 hours every day.”

Later, OCD and attendant tics were viewed as manifestations of eccentricity. The renowned lexicographer Samuel Johnson (1709–1784) was described by a friend: “ … he whirled and twisted about to perform his gesticulations; and as soon as he had finish'd, he would give a sudden spring and make such an extensive stride over the thresholds, as if he were trying for a wager how far he could stride. …” (2). Esquirol (3) described a woman with “monomaniacal” obsessions and rituals. Westphal (4) gave a clear description of the syndrome. Janet (5) and Freud (6) also provided phenomenological descriptions of OCD, which still ring true today.

Etiology

Theories of etiology often imbue treatments with merit more apparent than real. Sir Clifford Allbutt's (7) observations about the etiology of atherosclerosis also apply to OCD:

It is when we come to study the causes of diseases that we are most disconcerted by the breadth and depth of our ignorance; it is here that our path is most cumbered with guesses, presumptions and conjectures, the untimely and sterile fruitage of minds which cannot bear to wait for the facts, and are ready to forget that the use of hypotheses lies not in the display of ingenuity but in the labor of verification.

Behaviorists emphasize anxiety acquisition through the pairing of a neutral event with an aversive experience that evokes anxiety or other discomfort. Behaviors (avoidance and observable or mental rituals) that decrease anxiety or other discomfort are repeated because of their beneficial effect but become problems in their own right as they prevent habituation and become excessive (8).

Abnormalities of serotonin neurotransmission are current popular explanations of OCD and are amenable to many biochemical research paradigms (9). Anatomic circuits and metabolic abnormalities have been hypothesized or demonstrated (10), and there is an active pursuit of many lines of research that contribute to an understanding of the abnormalities associated with OCD. It is tempting to speculate that, regardless of the anatomic, metabolic, and biochemical derangements of OCD, the problem may be one of severity and not of type. The main themes of obsessions lie on the dimension of danger, and patients feel compelled to perform rituals that lessen those anxieties, albeit incompletely. There is an obvious evolutionary advantage in being appropriately concerned about danger and in checking, cleaning, grooming, washing, counting, ordering, straightening, and storing enough but not too much (11, 12).

The undoubted mediation of OCD through gene expression begs the question, which genes? Although evidence is beginning to emerge that specific genes are involved in OCD, it is probable that different combinations of genes will be involved even in phenotypically similar OCD. For example, assessment of serotonin system candidate genes in 54 parent-child trios showed no evidence for association at any of the polymorphisms in any subjects, perhaps because of low power across individual association studies (13). Even more recently, glimmerings of genetic understanding have emerged: “Using compulsive hoarding as the phenotype, there was suggestive linkage to chromosome 14 at marker D14S588 (Kong and Cox logarithm of the odds ratio [LOD] [KACall=2.9]). In families with two or more hoarding relatives, there was significant linkage of OCD to chromosome 14 at marker C14S1937 (KACall=3.7), whereas in families with fewer than two hoarding relatives, there was suggestive linkage to chromosome 3 at marker D3S2398 (KACall=2.9)” (14). Notably, this article listed 22 authors from five universities, and there was an accompanying editorial to further describe the meanings, promise, and limitations of our present understanding. Still, the future timing of definitive elucidation of pathological gene patterns remains indeterminate, and the ability to manipulate gene function to therapeutic advantage is still further removed.

The complexity of genetic research is reflected in a “Perspective” in a recent issue of the New England Journal of Medicine: “For the clinician, the outcome of these (genome-wide association) studies will be similar to those of any new investigative technology. The first results will need to be verified in similar populations by independent groups. Then, the usefulness of the variants for clinical practice will depend on their improving diagnostic prediction or fostering changes in prevention or treatment strategies. There is a compelling need for more, and more efficient, epidemiological studies so that these new approaches can be exploited. To meet this need, scientists and clinicians must collect information, informed consent, and tissue samples in the expectation of future studies that will address as yet unformed questions” (15).

It is helpful for patients and clinicians to have a conceptual etiological model on which to hang their hats. Although oversimplified, concern for safety with avoidance of excessive harm, risk, and danger is probably normally distributed in the population. Under the broad part of a bell-shaped curve, this characteristic conveys a survival advantage for the individual and the genes he or she carries. At either tail of the curve, with excessive or negligible concern for safety, gene transmission is reduced. Those with OCD and excessive concern about safety (e.g., contamination obsessions about sex) are less likely to mate and reproduce, whereas those without fear may not live long enough to reproduce.

Phenomenology

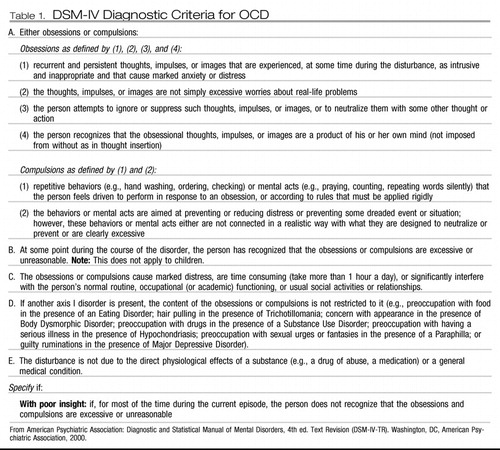

As its name implies, OCD is characterized by obsessions and compulsions. Obsessions are unwanted intrusive ideas, images, or impulses that patients often experience as senseless, thereby demonstrating that they have preservation of insight and are not delusional. Patients often feel besieged by their incessant obsessions, confirming the appropriateness of the derivation from the Latin obsidere, which means “to besiege.” The most common obsessions involve themes of harm, risk, or danger, which include contamination, doubt, aggressivity, disorder, and loss of things of importance. Compulsions are urges that patients experience to lessen their anxiety, discomfort, dysphoria, or feelings of disgust that usually emanate from obsessions. Compulsions typically lead to performance of repetitive, purposeful, intentional behaviors called rituals. Rituals help individuals achieve transient reduction in discomfort from obsessions, but at a cost of having to be done to excess. Washing and cleaning usually relieve concerns about contamination; checking reduces doubts; avoiding objects of aggression or the implements with which one might be aggressive allays anxiety about aggression; straightening and ordering decrease discomfort from disorder; and hoarding counteracts fears of losing things. Avoidance of situations that would evoke obsessions and consequent rituals and various forms of checking summarize many subtypes of obsessions and rituals and should be sought in the mental status examination as signals of OCD (16). The DSM-IV-TR (APA) diagnostic criteria for OCD are presented in Table 1.

|

Table 1. DSM-IV Diagnostic Criteria for OCD

Although ritualistic behaviors are often observable, they may take the form of mental behaviors. Thus, a parent obsessed with horrific images of slaughtering her family members may repeat, sotto voce, “God would never let me harm my family, God would never let me harm my family.” Rituals must be repeated because patients feel uncertain that they have done enough to prevent harm, risk, or danger. These major themes account for about 80% of obsessions and compulsions, but the protean nature of obsessions and the rituals that relieve them are legendary, and most patients have several obsessions and compulsions. Fewer than 5% of patients have only obsessions or compulsions, and these singular claims are suspect and often overlook mental rituals that are confused with obsessions because both occur as thoughts. The distinction is easily made: obsessions are thoughts that intrude and are anxiogenic; mental rituals are mental behaviors performed by the person and are anxiolytic.

Many disorders share phenomenological similarities with OCD. Patients with hypochondriasis are obsessed with the idea that they have a dread disease and compulsively seek repeated examinations from physicians to diagnose the malady. When the physician reassures them that there is no evidence of disease, they are relieved, but only briefly, because reassurance, as other rituals, provides no lasting benefit. Somatization disorder, body dysmorphic disorder, eating disorders, nail biting, and some impulse control disorders (e.g., trichotillomania, kleptomania, and pathological gambling) (17) are sometimes conceptualized as part of an obsessive-compulsive spectrum. Some spectrum patients respond to the same treatments effective in patients with OCD.

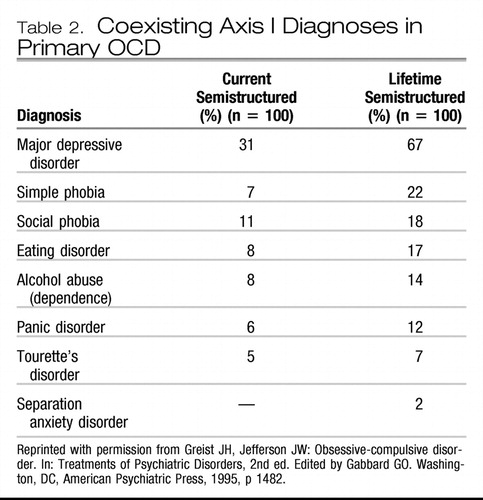

Most patients with OCD hide their obsessions and rituals because they fear stigmatization should they be discovered. Jenike (18) has called OCD a hidden epidemic. Few patients disclose obsessions and compulsions directly to physicians, but many complain about comorbid conditions (19). Two thirds of patients with OCD have a major depressive episode during their lifetimes. Other anxiety disorders and Gilles de la Tourette syndrome are much more common in patients with OCD than in the general population (Table 2) (20). Personality disorders, particularly cluster C (anxious-fearful) disorders, occur in about 60% of patients with OCD (21).

|

Table 2.

Epidemiology

OCD is quite common, with 1-month and lifetime prevalences of 1.3% and 2.5%, respectively (22, 23). Early onset is common, with mean ages in males and females of 18 and 21 years, respectively. Prepubertal onset is frequent, and some grade-school children are incapacitated to the point that they cannot attend school (11, 12). The most recent National Comorbidity Survey Replication (24) found a consonant 12-month prevalence of 1.0% with 51% of patients with “serious” severity defined primarily as 30 days or more out of their major role in the year.

After onset, OCD usually runs a chronic course of waxing and waning severity; few patients have spontaneous remissions, and about 10% experience a devastating downhill course until their lives become dominated by the disorder. On average, patients who seek treatment have waited a decade after symptoms emerged before doing so. OCD is a familial disorder; slightly more than 20% of an index patient's family members also have OCD, and others have stigmata of the disorder but do not meet full diagnostic criteria (19). OCD occurs in all cultures and races, although some cultures continue to believe that OCD is a religious affliction. Other cultures believe that individuals with OCD are merely willful, and still others view OCD as an illness or disorder.

Pathophysiology

Many biological aspects of the pathophysiology of OCD are being studied intensively. Different imaging techniques and biochemical assays and probes generally support the following findings:

| 1. | Orbitofrontal cortex, anterior cingulate cortex, and caudate nuclei of patients with OCD exhibit increased metabolism compared with control subjects (25, 26). | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2. | Effective short-term treatment with a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) [fluoxetine (Prozac)] or behavior therapy (exposure and response prevention) (10) reduces hypermetabolism in the right caudate nucleus, whereas effective long-term treatment with a potent serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SRI) [clomipramine (Anafranil)] reduces hypermetabolism in the orbitofrontal cortex (27). | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3. | Serotonin is significantly involved in OCD because

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4. | Potent noradrenergic reuptake inhibitors such as desipramine (Norpramin) are ineffective treatments for OCD. | ||||||||||||||||||||||

Knowledge is accumulating about the anatomy, metabolic abnormalities, and neurochemistry of OCD, but the pathophysiology of the disorder is not definitively understood (31).

Diagnosis

Accurate diagnosis guides and should precede treatment. Fortunately, when obsessions and rituals are disclosed, diagnosis is seldom difficult, with sophistication needed only to identify rare primary etiologies such as brain lesions or streptococcal infections that produce secondary obsessions and rituals. Unfortunately, because they recognize the excessiveness and inappropriateness of their symptoms, many patients hide manifestations of OCD, causing an average delay from symptom onset to diagnosis of 11 years (32). Stigmata such as chapped hands from washing and habitual appointment tardiness from time spent doing rituals easily prompt simple screening questions: Do you have repeated and annoying ideas, images, or impulses that seem silly, weird, or nasty? Are there things you feel compelled to do or thoughts you must think repeatedly and to excess? Do these thoughts and behaviors cause distress or interfere with your functioning? (See Table 1.)

Assessment

Several assessments of the nature and severity of OCD are available, although most practitioners have neither time, training, nor inclination to use them, trusting instead their more global impressions. The merit of measurement is real and can be realized by turning the task over to the patient who is the subject expert on symptomatology. Sharing this burden adds further value as patient and clinician have more consensus on status, and this factor has been shown to increase treatment efficacy (33).

The gold standard Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS) (see Appendix A) was used in all randomized controlled trials that led to Food and Drug Administration (FDA) medication approvals for OCD. There is also a children's version (CY-BOCS). Ten items, five for obsessions and five for compulsions/rituals can be scored by clinicians or equally well by almost all adult patients using either a paper and pencil or computer interview versions (34). Scores ≤10 indicate subclinical illness, 11–16 mild illness, 17–24 moderate illness, 25–32 marked illness, and 33–40 severe illness.

The Y-BOCS Symptom Checklist (see Appendix B) identifies more than 60 obsessions and rituals and is very helpful in defining the extent of past and present pathology. Asking patients to indicate severity for each present obsession and ritual on a 0 (none) to 10 (most severe imaginable) scale permits refined follow-up of change as treatment proceeds. These two self-report Y-BOCS assessments provide accurate information about the patient's OCD and effectiveness of treatment. Other assessments may be used but are not as widely recognized or understood, and we prefer the Y-BOCS.

Treatment

Until 1966, OCD was properly considered a refractory disorder for which only neurosurgery was inconsistently effective. “Despite Freud's acclaimed success in curing the ‘Rat Man' (6), analytic approaches have not been studied systematically or shown to be helpful, and the limitations of this approach are often acknowledged by analysts: ‘It is apparently true, for instance, that there is no known authenticated case of an obsessive handwasher being cured by psychoanalytic treatment'” (35, 36). Trials of a broad range of psychopharmacological agents were equally ineffective.

In 1966, clomipramine was released in Switzerland, and behavior therapy was tried in OCD. Both were dramatically beneficial against the backdrop of previous treatment failures (37, 38). As with many defining psychiatric therapies emerging in that era (e.g., chlorpromazine for schizophrenia and lithium for bipolar disorder), little, if any, greater efficacy has emerged since then beyond the marginal advantage of multiple medications with similar mechanisms but different structures, each helping fractionally more patients, and hard won nuanced knowledge about pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic effects of medication combinations. SSRIs do have a better side effect and safety profile than clomipramine and are preferred as first line drug treatment for that reason.

Behavior therapy

Following Meyer's lead, clinicians have conducted numerous randomized clinical trials that confirm the principal value of exposure and response (now called ritual) prevention as the behavioral treatment of choice for OCD. Greater short-term (39–42) and lasting benefits (43) of behavior therapy compared with benefits with medications is well documented. The value of this behavior therapy for children, adolescents, and adults is recognized in all treatment guidelines for OCD (44–49). Two landmark studies summarize what is known without oversimplifying complexity that requires individualization of treatments.

In adults, Foa et al. (50) compared clomipramine with behavior therapy, their combination, and pill placebo as 12-week treatments for OCD. A figure in their article [which is reprinted in this issue beginning on page Original article: 368] confirms the chronicity of OCD treated with placebo and shows that clomipramine was significantly more efficacious than placebo and that behavior therapy was significantly more efficacious than clomipramine, whereas the combination was not better than behavior therapy alone.

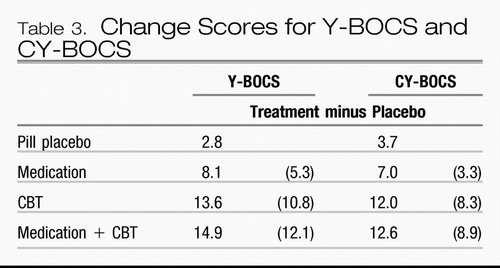

In children and adolescents, the Pediatric OCD Treatment Study (POTS) (51) compared sertraline with cognitive behavior therapy (CBT), their combination, and placebo pill, also for 12 weeks. Results were quite similar to those found in the Foa et al. (50) study in adults. Table 3 shows change scores for the Y-BOCS and its child version CY-BOCS.

|

Table 3.

Forty hours of face-to-face behavior therapy was used in the adult study and 14 hours in the child study. In both studies, treatment-placebo numeric improvement on the Y-BOCS was at least twice as large for CBT as for the FDA-approved SRI medication against which CBT was compared. Combined treatment was little better than CBT alone. The combination did result in lower medication doses in both studies (163 mg/day in combination with CBT versus 196 mg/day for clomipramine monotherapy in adults and 133 mg/day versus 170 mg/day for sertraline in children). The POTS study reminds us of Disraeli's dictum that “There are three kinds of lies: lies, damn lies, and statistics,” as statistical analysis showed the combination to be significantly better than CBT alone based on a numeric difference of 0.6 (out of more than 8 points on the Y-BOCS), whereas the larger numeric difference of 1.3 in the adult study did not! Site variability in results of CBT was significant in the POTS study. The CBT effect size at the Penn site (1.6) was more than three times larger than that at the Duke site (0.51), whereas medication differences were smaller (0.53 and 0.8, respectively). This suggests that therapy standardization is more difficult with CBT than with medication.

Despite the well-documented and marked advantage of CBT over medication for OCD, the likelihood of receiving CBT treatment ranged from only 5% (52) to 38% in the Brown (University) Longitudinal Obsessive Compulsive Study (53), although only 24% in the Brown study had at least 13 treatments within 1 year. Further, some patients have only relaxation, which is used as a placebo in randomized, controlled trials (RCTs) of other elements of CBT. The authors of the seminal adult and child studies shared similar laments:

“Expertise in exposure and ritual prevention is uncommon among clinicians in the community, perhaps because typical psychotherapists, even with cognitive behavior therapy training, do not treat sufficient numbers of OCD patients to acquire the experience necessary for effective intervention for patients with difficult-to-treat OCD. One solution is to develop regional specialty clinics similar to centers for heart disease and cancer (50).”

“Unfortunately, despite ready availability of the CBT protocol, only a small minority of children and adolescents with OCD receive state-of-the-art treatment(s) for reasons that may include features of the intervention itself as well as variables pertaining to the practitioner, client, model of service delivery, organization, and service system…. In this context, it is imperative that the focus of research turn to identifying and testing dissemination strategies for CBT as well as to procedures for managing partial response to medication monotherapy using CBT augmentation (51).”

One approach to making scarce CBT skills more widely available is therapy provided largely by telephone. After a single face-to-face assessment and introduction to CBT in trials in three different settings, weekly phone contacts over 8, 10, or 12 weeks lasted 15, 30, and 45 minutes, respectively, to design and encourage exposure and ritual prevention homework (54–56). Immediate posttreatment Y-BOCS reductions of 12.0, 9.2, and 10.9 were found, respectively, the last in a RCT comparing telephone and face-to-face CBT in which Y-BOCS score reduction was 10.3 when it was administered by the same therapists. Follow-ups of 1, 3, and 6 months, respectively, found maintenance of improvement. Satisfaction with telephone CBT was as high as with face-to-face CBT.

An alternate approach that provides effective behavior therapy without requiring clinicians to change how they practice is also possible. BT STEPS, a computer-assisted exposure and ritual prevention program teaches patients how to systematically self-manage their behavior therapy. In a RCT (57), 64% of patients did at least one exposure and ritual prevention homework session and decreased their Y-BOCS score by 7.8 points. Those randomly assigned to behavior therapists for 12 hours of face-to-face individual sessions decreased their Y-BOCS score by 8.1 points. There was a strong dose-response relationship with BT STEPS CBT. For those who did between 2 and 20 homework sessions the Y-BOCS score decreased 10.3 and with more than 20 sessions the score decreased 14.3 points. These improvements occurred without therapist coaching or support. Addition of these elements by scheduled telephone calls in another study increased the percentage of patients using BT STEPS, who did at least two exposure and ritual prevention sessions, from 57% to 95% and more than doubled Y-BOCS improvement (58). Therapist telephone calls averaged 13 minutes each, with a total mean time of 76 minutes per patient.

Although unstudied, the simplest approach to providing CBT where none is available is to give literate patients a self-help book to guide their efforts. A few determined patients have done well through this medium alone although a modicum of coaching and support from a clinician would probably speed and increase improvement. Clinicians also find these brief books useful sources of education (59–64).

Cognitive therapy

Cognitive therapists seek to change thoughts, feelings, and behaviors. They hypothesize that faulty cognitions permit and then maintain unpleasant affects and dysfunctional behaviors. Correcting faulty cognitions should lead to more agreeable affects and more functional behaviors. However, it is striking that in OCD, patients with insight have called their cognitions crazy thousands of times, family members have argued against their obsessional fears, and clinicians have agreed that their worries are unfounded, all without benefit.

Reviews (65, 66) have documented efficacy for cognitive procedures that address faulty risk assessment and exaggerated sense of responsibility. Whether cognitive therapy might achieve its benefits directly through cognitive means or, indirectly, by invoking exposure and ritual prevention is an important question (67).

Medications

“If many treatments are used for a disease, all are insufficient” as stated by Osler (68).

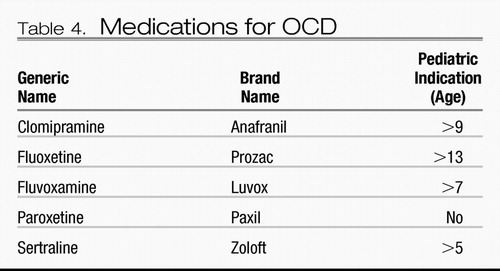

Several medications have received FDA indications for treatment of OCD in adult and pediatric populations (Table 4). Although other SSRIs and the serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor venlafaxine do not have FDA-approved indications for OCD, citalopram, escitalopram, and venlafaxine have demonstrated efficacy in RCTs and may reasonably be tried off-label after due consideration has been given to SRIs with FDA approvals. For example, escitalopram was as efficacious as paroxetine at 24 weeks in achieving ≥25% reductions in Y-BOCS scores (69), and both were more efficacious than placebo. In a 6-month, placebo-controlled relapse prevention study (70), relapse was 2.74 times greater with placebo than with escitalopram.

|

Table 4. Medications for OCD

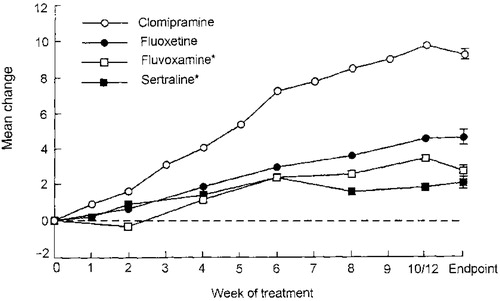

Clomipramine has demonstrated greater efficacy than SSRIs for adults in meta-analyses in which they have been compared (71–74) (Figure 1). Clomipramine also showed significantly greater efficacy than fluoxetine (p<0.03), fluvoxamine (p=0.001), paroxetine (p=0.003), and sertraline (p<0.001) in a meta-analysis of 1,044 children and adolescents with OCD (75). But as a tricyclic antidepressant, clomipramine also conveys a heavier side effect burden. Thus, SSRIs are the first-line medication treatment for OCD, with clomipramine usually being reserved for trials in patients who show insufficient improvement with a first or second SSRI. With SSRIs, it is impossible to predict responses, with the rare exception of identical twins, so any SSRI may be used first. We give consideration to patient preference, having provided information about likely limiting side effects including weight gain, discontinuation difficulty, and possible fetal risk during pregnancy and, importantly, cost. When SRIs are discontinued, rapid relapse is the rule rather than the exception (76, 77), an unfortunate occurrence in sharp contrast to CBT, for which gains to 6 years have been documented (43).

Figure 1. Mean Change in Y-BOCS Total Score. Intent-to-treat Analysis of Drug Minus Placebo. Pooled standard error of change score was used in error bars (available for endpoint only).

* Twelve weeks of treatment for fluvoxamine and sertraline.

Dosing

Many psychiatrists believe, with little supportive evidence, that OCD treatment requires large or even heroic dosing to achieve best results. This belief appears to arise from several sources and is understandable, well intentioned, and misguided. Before the availability of potent SRIs, there was no effective pharmacotherapy for OCD and that experience led some to the superficially logical but incorrect conclusion that whatever medication proved effective in OCD would need to be given in large doses. SSRIs have a large therapeutic index so high doses were more tolerable than with clomipramine for which the therapeutic index is narrow, limited both by typical tricyclic side effects and risk of seizure and cardiac arrhythmias. Despite the markedly better response to potent SRI antidepressants than the poor response to previously tried non-SRI monotherapies, remission virtually never occurred in adult patients, so the dose was increased in hopes of further benefit. Finally, with the higher doses a few patients did benefit, possibly because of particular pharmacokinetic or pharmacodynamic factors. These exceptions were thought to prove the rule that higher doses were better; but the rule they prove is that humans, in general, do a poor job of estimating complex risks, and human clinicians are no exception to this rule. Thus, there was no dose-response relationship in FDA OCD registration trials for fluoxetine or sertraline and no difference between 40 and 60 mg/day for paroxetine, with 40 mg/day being the lowest effective dose.

Although a significant dose-response relationship for efficacy does not exist with SRIs in OCD, the adverse effects dose-response relationship is clear. Children with OCD precipitated by pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococcus may be especially vulnerable to behavioral activation with high SRI doses (78).

A method that avoids the risk of excessive dosing while acknowledging the fact that a few individuals need larger doses than the norm is:

| •. | to begin with a small, but usually effective, dose (e.g., fluoxetine 20 mg/day), watch for a response and if the response occurs within 4 weeks, and | ||||

| •. | wait for the beneficial response to plateau, based on Y-BOCS scores, many weeks later. | ||||

| •. | At that point, dose should be increased (e.g., to fluoxetine 40 mg/day) to determine whether the patient benefits from a higher dose, again based on the Y-BOCS score. If further improvement results, the process is repeated until no further improvement is found or side effects limit any further dose increase. | ||||

| •. | If no improvement occurs with the dose increase, the dose is systematically reduced to the previous effective dose, thereby minimizing risk of side effects and cost. | ||||

| •. | This approach optimizes the dose, ensuring maximum improvement while minimizing side effects. Considering the chronicity of OCD, this deliberate approach to optimal dosing is appropriate. | ||||

Beyond basic psychopharmacology for OCD

Given the proven efficacy of SRIs in OCD, proserotonergic augmentation theories were logically advanced, and treatments derived from them were tested. Open trials suggested promise with the recommendation for placebo-controlled RCTs, which, unfortunately, showed no significant benefit from buspirone (79–81) or lithium (82, 83). Within the active treatment arms, some patients had some benefit so these augmentations may be worth trying in patients with partial, but insufficient, responses to SRIs alone.

Open-label combinations of clomipramine with fluvoxamine (84) and citalopram (85) produced greater improvement than monotherapies. Pharmacokinetic mechanisms were suggested to explain the fluvoxamine combination, and pharmacodynamic mechanisms were suggested for citalopram.

Best established are augmentations of SRIs with antipsychotics for treatment-resistant OCD. Following the placebo-controlled RCT with haloperidol augmentation of fluvoxamine of McDougle et al. (86), which showed clear benefits in patients with OCD and comorbid tics, other RCTs of antipsychotic augmentation have been conducted. By March 2006, 10 trials had been reported with haloperidol (N=1), olanzapine (N=2), risperidone (N=3), and quetiapine (N=4). These were subjected to a meta-analysis (87). The weighted combined response ratio with 157 patients receiving drug and 148 receiving placebo was 3.31 (95% confidence interval 1.40–7.84). Antipsychotic doses were modest and, within this low dose range, there may have been a dose-response relationship. In individuals with schizophrenia with and without comorbid OCD, atypical antipsychotic drugs have sometimes been associated with exacerbation or onset of OCD symptoms (88–92).

An open trial suggestion of benefit from SRI augmentation with oral morphine given weekly in treatment-resistant OCD (93) was confirmed in a placebo- and lorazepam-controlled RCT (94). The weekly administration interval suggested a mechanism different from that involved in pain relief.

Other somatic therapies

Electroconvulsive therapy was often tried in severe OCD before effective treatments became available, and sometimes since, and patients occasionally benefitted (95, 96). Responding patients probably had primary depression with secondary OCD symptoms, or they may have had exacerbation of primary OCD when a secondary depression, which occurs commonly, was superimposed. There is little indication and no convincing evidence that primary OCD responds to electroconvulsive therapy.

An open trial suggested that 20 minutes of right lateral prefrontal transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) at 80% of the motor threshold dose produced a reduction in obsessive-compulsive symptoms lasting 8 hours. Left lateral prefrontal TMS was ineffective and midoccipital stimulation increased obsessive-compulsive symptoms (97). Another open-label series also supported efficacy of TMS (98). However, three sham-controlled repetitive TMS studies (two right and one left prefrontal stimulation locations) found no difference between repetitive TMS and sham treatment arms (99–101). These results emphasize again the frequent difference between open and randomized, controlled trials of treatments and the high value for the profession and patients of publishing negative trial results.

An open trial of vagus nerve stimulation (102) in seven patients with treatment-resistant OCD was conducted. Acutely and at 6 months, three of seven patients (43%) had ≥25% reductions in Y-BOCS scores.

Neurosurgery, properly reserved for the most severe and incapacitating OCD, was sometimes beneficial before SRIs and CBT were available and has continued to prove helpful for a few patients when thorough trials of these favored treatments were truly ineffective (103). Anterior cingulotomy, subcaudate tractotomy, and their combination as limbic leucotomy as well as anterior capsulotomy were all used and created lesions in pathways between brain structures shown to be functioning abnormally in OCD. With modern neurosurgical techniques including stereotactic control, prospective studies have confirmed benefits (104, 105) and postoperative hemorrhage, infection, and seizures are uncommon, mortality is rare, and personality change, when it occurs, is usually favorable (106). Preoperative positron emission tomography scans of the right posterior cingulate cortex may identify patients more likely to have a good response to anterior cingulotomy (107).

Deep brain stimulation via removable electrical leads placed bilaterally in the anterior limb of the internal capsule (one site of effective ablative procedures) has proven helpful for a small but growing number of patients with carefully documented intractable OCD (108–110) The largest series, combined from three pilot studies in Antwerp/Leuven, Providence, RI/Cleveland, OH, and Gainesville, FL, has followed 26 patients (111). Overall the mean Y-BOCS score decreased >35% and more than 50% of patients achieved this excellent outcome as well as a substantial increase in Global Assessment of Functioning scores from a baseline of 25–41 to a score >50. Twelve patients have been followed for >3 years with lasting improvements unless stimulation was interrupted. Few adverse events, none serious, were reported across the full population. There were no group-level neuropsychological declines after a mean of 10 months of stimulation in the 10 Providence, RI/Cleveland, OH, patients. Surprisingly, visuospatial skill, visual learning, and story memory improved.

All of these other somatic therapies remain experimental and require subspecialty knowledge, skills, and specific written informed consent for their application.

Conclusions

We have emphasized results from RCTs, where available, to provide evidence-based guidance for treatment of OCD. These emphases are expressed mainly in mean scores or average results. But none of our patients is average—each is an individual, and these data on mean effects represent only a starting point from which to plan individual treatment.

Getting long in the tooth ourselves, we look back across decades of preoccupation with pathophysiology and continued fascination with mechanisms of action of medications at the expense of translating what is known empirically about treatment into helpful practice. We struggle to adhere to Carlyle's admonition: “Our main business is not to see what lies dimly at a distance, but to do what lies clearly at hand” (112). However, none of this criticism diminishes the importance of research that will ultimately improve our understanding of OCD and its treatments.

What are the best treatments we can offer patients with OCD based on what we know now? All are best served if we understand and accept proven knowledge, including physicians' inability to apply what we know is best treatment. Particularly annoying is our failure to accept, adopt, and apply CBT as the treatment of choice for OCD. Table 3 shows that treatment-minus-placebo Y-BOCS reductions with CBT are more than double those with clomipramine and sertraline in the definitive adult and pediatric OCD trials (10.8 versus 5.3 and 8.3 versus 3.3, respectively). In addition, relapse after medication discontinuation is the rule, but relapse after CBT is uncommon.

That our reach always exceeds our grasp is not unique to psychiatrists. In 1976, internal medicine residents complied with only 22% of 390 obvious and important practice protocols (113). Their compliance improved to 55% after introduction of an innovation, but returned to baseline when it was removed. Twenty-five years later in the same institution, influenza immunizations were provided to only 1% of inpatients aged 65 and older until the innovation was used and raised immunization rates to 55% (114). The innovation was computer reminders to the doctors regarding their own practice protocols. The amount they still fell short of their practice goals was attributed to “the nonperfectability of man.” We care about influenza immunizations because poor practice produces poor outcomes. Immunization of elderly individuals reduces hospitalizations for cardiac and cerebrovascular disease by 19%, for pneumonia or influenza by 30%, and for all causes deaths by 49% (115).

For those wanting to offer the best treatment to patients with OCD who want it, CBT with exposure and ritual prevention is the answer. The essence is exposure to triggers of anxiety followed by foregoing rituals that reduce anxiety—a treatment that must be self-administered so the clinician's role is to guide and coach the patient. Once established, CBT becomes a way of life, changing inappropriate risk aversion to therapeutic risk taking, where the risks are not really risky, and providing large and lasting improvements.

Successive trials of SRIs, dosed properly for sufficient duration and then continued indefinitely, is also effective treatment for OCD. The magnitude of SRI benefits (effect size) is about half that for CBT, and benefits usually disappear shortly after medication is discontinued. Augmentation with atypical antipsychotic drugs appears helpful, and other combinations with less evidence supporting their efficacy may also help some patients. The side effect burden of medications must be managed as well as ongoing cost.

Patients who have access to CBT and medication sometimes do better than either alone and with CBT, have the possibility of discontinuing medication without substantial worsening of OCD.

For patients with intractable and incapacitating OCD, neurosurgical lesions have sometimes been helpful. Deep brain stimulation in the same areas has demonstrated improvement to at least 3 years without irreversible lesions.

And finally, we advocate measuring treatment effects systematically and sharing assessment results with the patient. The patient is the subject expert on his or her symptoms and functioning, so repeated patient-completed Y-BOCS scores are ideal. This simple step yokes doctor and patient into a strong team to lessen the heavy burden of OCD.

Appendix A.

Reprinted with permission from Greist JH, Jefferson JW, Kobak KA, Katzelnick DJ, Serlin RC: Efficacy and tolerability of serotonin transport inhibitors in obsessive-compulsive disorder: a meta-analysis. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1995; 52:53–60. Copyright 1995, American Medical Association.

Appendix B.

1 Pitman RK: Obsessive compulsive disorder in Western history, in Current Insights in Obsessive Compulsive Disorder. Edited by Hollander E, Zohar J, Marazziti D, Oliver B. Chichester, NY: John Wiley & Sons; 1994, pp 3– 10Google Scholar

2 Rapoport JL: The Boy Who Couldn't Stop Washing: The Experience & Treatment of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. New York, Penguin Books; 1989, p 4Google Scholar

3 Esquirol JED: De la monomanie, in Des maladies mentales. vol 1. Brussels, Belgium, JB Baillirie, 1838Google Scholar

4 Westphal C: Dwangforstellungen. Arch Psychiatr Nervenkrank 1878; 8: 734– 750Google Scholar

5 Janet P: Les Obsessions et la Psychastenie. 2nd ed. Paris: Valilèrel, 1908Google Scholar

6 Freud S: Notes upon a case of obsessional neurosis (1909), in Collected Papers, vol. 3. Edited by Jones E. London, Hogarth Press, 1925, pp 293– 383Google Scholar

7 Allbutt C: Diseases of the arteries including angina pectoris, vol 1. London: Macmillan, 1915, p 154Google Scholar

8 Mowrer OH: Learning Theory and Behavior. New York, John Wiley & Sons, 1960Google Scholar

9 Jenike MA: Theories of etiology, in Obsessive Compulsive Disorders: Theory and Management, 2nd ed. Edited by Jenike MA, Baer L, Minichiello WE. Chicago, Year Book Medical, 1990, pp 99– 117Google Scholar

10 Baxter LR, Schwartz JM, Bergman KS, Szuba MP, Guze BH, Mazziotta JC, Alazraki A, Selin CE, Ferng HK, Munford P, Phelps ME: Caudate glucose metabolic rate changes with both drug and behavior therapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1992; 49: 681– 689Crossref, Google Scholar

11 Greist JH, Jefferson JW: Obsessive-compulsive disorder, in Treatments of Psychiatric Disorders, 2nd ed. Edited by Gabbard GO. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1995, pp 1477– 1498Google Scholar

12 Greist JH, Jefferson JW.: Obsessive-compulsive disorder, in Treatments of Psychiatric Disorders, 3rd ed. Edited by Gabbard GO. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 2001, 1515– 1537Google Scholar

13 Dickel DE, Veenstra-Vanderweele J, Bivens NC, Wu X, Fischer DJ, Van Etten-Lee M, Himle JA, Leventhal BL, Cook EH, Hanna GL: Association studies of serotonin system candidate genes in early-onset obsessive-compulsive disorder. Biol Psychiatry 2007; 61: 322– 329Crossref, Google Scholar

14 Samuels J, Shugart YY, Grados MA, Willour VL, Bienvenu OJ, Greenberg BD, Knowles JA, McCracken JT, Rauch SL, Murphy DL, Wang Y, Pinto A, Fyer AJ, Piacentini J, Pauls DL, Cullen B, Rasmussen SA, Hoehn-Saric R, Valle D, Liang KY, Riddle MA, Nestadt G: Significant linkage to compulsive hoarding on chromosome 14 in families with obsessive-compulsive disorder: results from the OCD Collaborative Genetics Study. Am J Psychiatry 2007; 164: 493– 499Crossref, Google Scholar

15 Christensen K, Murray JC: What genome-wide association studies can do for medicine. N Engl J Med 2007; 356: 1094– 1097Crossref, Google Scholar

16 Greist JH, Jefferson JW: Obsessive-compulsive disorder, in Treatments of Psychiatric Disorders, 2nd ed. Edited by Gabbard GO. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1995, p 1481Google Scholar

17 Hollander E (ed): Obsessive-Compulsive-Related Disorders. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1993Google Scholar

18 Jenike MA: Obsessive-compulsive and related disorders: a hidden epidemic. N Engl J Med 1989; 321: 539– 541Crossref, Google Scholar

19 Rasmussen SA, Eisen JL: Epidemiology, clinical features and genetics of obsessive-compulsive disorder. In: Understanding Obsessive-Compulsive Behavior. Edited by Jenike MA, Asberg M. New York, Hogrefe & Huber, 1991, pp 17– 23Google Scholar

20 Greist JH, Jefferson JW: Obsessive-compulsive disorder, in Treatments of Psychiatric Disorders, 2nd ed. Edited by Gabbard GO. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1995Google Scholar

21 Baer L, Jenike MA, Black DW, Treece C, Rosenfeld R, Greist J: Effect of axis II diagnoses on treatment outcome with clomipramine in 55 patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1992; 49: 862– 866Crossref, Google Scholar

22 Karno M, Golding JM, Sorenson SB, Burnam MA: The epidemiology of obsessive-compulsive disorder in five US communities. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1988; 45: 1094– 1099Crossref, Google Scholar

23 Regier DA, Boyd JH, Burke JD Jr, Rae DS, Myers JK, Kramer M, Robins LN, George LK, Karno M, Locke BZ: One-month prevalence of mental disorders in the United States: based on five Epidemiologic Catchment Area sites. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1988; 45: 977– 986Crossref, Google Scholar

24 Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, Walters EE: Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2005; 62: 617– 627Crossref, Google Scholar

25 Baxter LR JR, Phelps ME, Mazziotta JC, Guze BH, Schwartz JM, Selin CE: Local cerebral glucose metabolic rates in obsessive-compulsive disorder: a comparison with rates in unipolar depression and in normal controls (published erratum appears in Arch Gen Psychiatry 1987; 44:800). Arch Gen Psychiatry 1987; 44: 211– 218Crossref, Google Scholar

26 Swedo SE, Schapiro MB, Grady CL, Cheslow DL, Leonard HL, Kumar A, Friedland R, Rapoport SI, Rapoport JL: Cerebral glucose metabolism in childhood-onset obsessive-compulsive disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1989; 46: 518– 523Crossref, Google Scholar

27 Swedo SE, Pietrini P, Leonard HL, Schapiro MB, Rettew DC, Goldberger EL, Rapoport SI, Rapoport JL, Grady CL: Cerebral glucose metabolism in childhood-onset obsessive-compulsive disorder: revisualization during pharmacotherapy. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1992; 49: 690– 694Crossref, Google Scholar

28 Woods A, Smith C, Szewczak M, Dunn RW, Cornfeldt M, Corbett R: Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors decrease schedule-induced polydipsia in rats: a potential model for obsessive compulsive disorder. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1993; 112: 195– 198Crossref, Google Scholar

29 Deas-Nesmith D, Brewerton TD: A case of fluoxetine-responsive psychogenic polydipsia: a variant of obsessive-compulsive disorder? J Nerv Ment Dis 1992; 180: 338– 339Crossref, Google Scholar

30 Rapaport JL, Ryland DH, Kriete M: Drug treatment of canine acral lick: an animal model of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1992; 49: 517– 521Crossref, Google Scholar

31 Greist JH, Jefferson JW: Obsessive-compulsive disorder, in Treatments of Psychiatric Disorders, 2nd ed. Edited by Gabbard GO. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press 1995Google Scholar

32 Rasmussen SA, Eisen JL: Clinical features and phenomenology of obsessive compulsive disorders. Psychiatr Ann 1989; 19: 67– 73Crossref, Google Scholar

33 Lambert MJ, Harmon C, Slade K, Whipple JL, Hawkins EJ: Providing feedback to psychotherapists on their patients' progress: clinical results and practice suggestions. J Clin Psychol 2005; 61: 165– 174Crossref, Google Scholar

34 Rosenfeld R, Dar R, Anderson D, Kobak KA, Greist JH: A computer-administered version of the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale. Psychol Assess 1992; 4: 329– 332Crossref, Google Scholar

35 Malan D: Individual Psychotherapy and the Science of Psychodynamics. London, Butterworths, 1979, pp 218– 219Google Scholar

36 Greist JH, Jefferson JW: Obsessive-compulsive disorder, in Treatments of Psychiatric Disorders, 2nd ed. Edited by Gabbard GO. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 2001Google Scholar

37 van Renynghe de Voxvrie G: Use of Anafranil (G 34586) in obsessive neuroses. Acta Neurol Belg 1968; 68: 787– 792Google Scholar

38 Meyer V: Modification of expectations in cases with obsessional rituals. Behav Res Ther 1966; 4: 273– 280Crossref, Google Scholar

39 Foa EB, Franklin ME, Kozak MJ: Psychosocial treatments for obsessive compulsive disorder: literature review, in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: Theory, Research, and Treatment. Edited by Swinson RP, Antony MM, Rachman S, Richter MA. New York, Guilford, 1998, pp 258– 276Google Scholar

40 Marks IM, Hodgson R, Rachman S: Treatment of chronic obsessive compulsive neurosis with in vivo exposure: a 2-year follow-up and issues in treatment. Br J Psychiatry 1975; 127: 349– 364Crossref, Google Scholar

41 Rachman S, Marks IM, Hodgson R: The treatment of obsessive-compulsive neurotics by modeling and flooding in vivo. Behav Res Ther 1973; 11: 463– 471Crossref, Google Scholar

42 Steketee G, Foa EB, Grayson JB: Recent advances in the behavioral treatment of obsessive-compulsives. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1982; 39: 1365– 1371Crossref, Google Scholar

43 O'Sullivan G, Noshirvani H, Marks I, Monteiro W, Lelliott P: Six-year follow-up after exposure and clomipramine therapy for obsessive compulsive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 1991; 52: 150– 155Google Scholar

44 Clinical Practice Guidelines: Management of anxiety disorders—principles of diagnosis and management of anxiety disorders. Can J Psychiatry 2006; 51: (8 suppl 2) S9– S21Crossref, Google Scholar

45 Passmore MJ, Garnham J, Duffy A, MacDougall M, Munro A, Slaney C, Teehan A, Alda M: Phenotypic spectra of bipolar disorder in responders to lithium versus lamotrigine. Bipolar Disord 2003; 5: 110– 114Crossref, Google Scholar

46 Allen A, Hollander E: Diagnosis and treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Prim Psychiatry 2005; 12: 34– 44Google Scholar

47 Franklin ME, Rynn MA, Foa EB, March JS: Pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder, in Phobic and Anxiety Disorders in Children and Adolescents: A Clinician's Guide to Effective Psychosocial and Pharmacological Interventions. Edited by Ollendick TH. New York, Oxford University Press 2004, pp 381– 404Google Scholar

48 Jenike MA: Clinical practice: obsessive-compulsive disorder. N Engl J Med 2004; 350: 259– 265Crossref, Google Scholar

49 Greist JH, Bandelow B, Hollander E, Marazziti D, Montgomery SA, Nutt DJ, Okasha A, Swinson RP, Zohar J: WCA recommendations for the long-term treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder in adults. CNS Spect 2003; 8: (8 suppl 1) 7– 16Crossref, Google Scholar

50 Foa EB, Liebowitz MR, Kozak MJ, Davies S, Campeas R, Franklin ME, Huppert JD, Kjernisted K, Rowan V, Schmidt AB, Simpson HB, Tu X: Randomized, placebo-controlled trial of exposure and ritual prevention, clomipramine, and their combination in the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Am J Psychiatry 2005; 162: 151– 161Crossref, Google Scholar

51 Cognitive-behavior therapy, sertraline, and their combination for children and adolescents with obsessive-compulsive disorders: the Pediatric OCD Treatment Study (POTS) randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2004; 292: 1969– 1976Crossref, Google Scholar

52 Torres AR, Prince MJ, Pebbington PE, Bhugra DK, Bhugra TS, Farrell M, Jenkins R, Lewis G, Meltzer H, Singleton N: Treatment seeking by individuals with obsessive-compulsive disorder from the British psychiatric morbidity survey of 2000. Psychiatric Services 2007; 58: 977– 982Crossref, Google Scholar

53 Mancebo MC, Eisen JL, Pinto A, Greenberg BD, Dyck IR, Rasmussen SA: The Brown Longitudinal Obsessive Compulsive Study: treatments received and patient impressions of improvement. J Clin Psychiatry 2006; 67: 1713– 1720Crossref, Google Scholar

54 Lovell K: Fullalove L, Garvey R, Brooker C: Telephone treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Behav Cogn Psychotherapy 2000; 28: 87– 91Crossref, Google Scholar

55 Taylor S, Thordarson DS, Spring T, Yeh AH, Corcoran KM, Eugster K, Tisshaw C: Telephone-administered cognitive behavior therapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder. Cogn Behav Ther 2003; 32: 13– 25Crossref, Google Scholar

56 Lovell K, Cox D, Haddock G, Jones C, Raines D, Garvey R, Roberts C, Hadley S: Telephone administered cognitive behaviour therapy for treatment of obsessive compulsive disorder: randomised controlled non-inferiority trial. BMJ 2006; 333: 883Crossref, Google Scholar

57 Greist JH, Marks IM, Baer L, Kobak KA, Wenzel KW, Hirsch MJ, Mantle JM, Clary CM: Behavior therapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder guided by a computer or by a clinician compared with relaxation as a control. J Clin Psychiatry 2002; 63: 138– 145Crossref, Google Scholar

58 Kenwright M, Marks I, Graham C, Franses A, Mataix-Cols D: Brief scheduled phone support from a clinician to enhance computer-aided self-help for obsessive-compulsive disorder: randomized controlled trial. J Clin Psychol 2005; 61: 1499– 1508Crossref, Google Scholar

59 Hyman BM, Pedrick C: The OCD Workbook: Your Guide to Breaking Free From Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder, 2nd ed. Oakland, Calif, New Harbinger 2005, pp 1– 237Google Scholar

60 Neziroglu F, Bubrick J, Yaryura-Tobias JA: Overcoming Compulsive Hoarding: Why You Save & How You Can Stop It. Oakland, Calif, New Harbinger, 2004, pp 1– 146Google Scholar

61 Foa EB, Wilson R: Stop Obsessing!: How to Overcome Your Obsessions and Compulsions, revised ed. New York, Bantam Books, 2001, pp 1– 253Google Scholar

62 Baer L: Getting Control: Overcoming Your Obsessions and Compulsions, revised ed. New York, Penguin Books, 2000, pp 1– 258Google Scholar

63 Greist JH: Obsessive Compulsive Disorder: A Guide, 5th ed. Madison, Wis, Madison Institute of Medicine 2000, pp 1– 55Google Scholar

64 March JS, Benton CM: Talking back to OCD: The Program That Helps Kids and Teens Say “No Way” – and Parents Say “Way to Go.” New York, Guilford, 2007, pp 1– 277Google Scholar

65 Deacon BJ, Abramowitz JS: Cognitive and behavioral treatments for anxiety disorders: a review of meta-analytic findings. J Clin Psychol 2004; 60: 429– 441Crossref, Google Scholar

66 Van Balkom AJLM, De Haan E, Van Oppen P: Cognitive and behavioral therapies alone versus in combination with fluvoxamine in the treatment of obsessive compulsive disorder. J Nerv Ment Dis 1998; 186: 492– 499Crossref, Google Scholar

67 Greist JH, Jefferson JW: Obsessive-compulsive disorder, in Treatments of Psychiatric Disorders, 3rd ed. Edited by Gabbard GO. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 2001Google Scholar

68 Aphorism #211, in Osler Aphorisms. Edited by Bean WB. New York, Henry Schuman, 1950, p. 101Google Scholar

69 Stein DJ, Tonnoir B, Andersen EW, Fineberg N: Escitalolpram in the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 2006; 16: (suppl) S295Google Scholar

70 Fineberg N, Lemming O, Tonnoir B, Stein DJ: Escitalopram in relapse prevention in patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 2006; 16: (suppl) S292Google Scholar

71 Ackerman DL, Greenland S: Multivariate meta-analysis of controlled drug studies for obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2002; 22: 309– 317Crossref, Google Scholar

72 Kobak KA, Greist JH, Jefferson JW, Katzelnick DJ, Henk HJ: Behavioral versus pharmacological treatments of obsessive compulsive disorder: a meta-analysis. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1998; 136: 205– 216Crossref, Google Scholar

73 Greist JH, Jefferson JW, Kobak KA, Katzelnick DJ, Serlin RC: Efficacy and tolerability of serotonin transport inhibitors in obsessive-compulsive disorder: a meta-analysis. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1995; 52: 53– 60Crossref, Google Scholar

74 Greist JH, Jefferson JW: Obsessive-compulsive disorder, in Treatments of Psychiatric Disorders, 2nd ed. Edited by Gabbard GO. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1995Google Scholar

75 Geller DA, Biederman J, Stewart SE, Mullin B, Martin A, Spencer T, Faraone SV: Which SSRI? a meta-analysis of pharmacotherapy trials in pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder. Am J Psychiatry 2003; 160: 1919– 1928Crossref, Google Scholar

76 Pato M, Zohar-Kadouch R, Zohar J, Murphy DL: Return of symptoms after discontinuation of clomipramine in patients with obsessive compulsive disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1988; 145: 1521– 1525Crossref, Google Scholar

77 Ravizza L, Maina G, Alberg U, Bogetto F: Long term management of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 1999; 9: (suppl 5) S186– S198Google Scholar

78 Murphy TK, Storch EA, Strawser MS: SSRI-induced behavioral activation in the PANDAS subtype. Prim Psychiatry 2006; 13: 87– 89Google Scholar

79 Grady TA, Pigott TA, L'Heureux F, Hill JL, Bernstein SE, Murphy DL: Double-blind study of adjuvant buspirone for fluoxetine-treated patients with obsessive compulsive disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1993; 150: 819– 821Crossref, Google Scholar

80 McDougle CJ, Goodman WK, Leckman JF, Holzer JC, Barr LC, McCance-Katz E, Heninger GR, Price LH: Limited therapeutic effect of addition of buspirone in fluvoxamine-refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1993; 150: 647– 649Crossref, Google Scholar

81 Pigott TA, L'Heureux F, Hill JL, Bihari K, Bernstein SE, Murphy DL: A double-blind study of adjuvant buspirone hydrochloride in clomipramine-treated patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1992; 12: 11– 18Google Scholar

82 McDougle CJ, Price LH, Goodman WK, Charney DS, Heninger GR: A controlled trial of lithium augmentation in fluvoxamine refractory obsessive-compulsive disorders: lack of efficacy. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1991; 11: 175– 184Crossref, Google Scholar

83 Pigott TA, Pato MT, L'Heureux F, Hill JL, Grover GN, Bernstein SE, Murphy DL: A controlled comparison of adjuvant lithium carbonate or thyroid hormone in clomipramine-treated OCD patients. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1991; 11: 242– 248Crossref, Google Scholar

84 Szegedi A, Wetzel H, Leal M, Hartter S, Hiemke C: Combination treatment with clomipramine and fluvoxamine: drug monitoring, safety, and tolerability data. J Clin Psychiatry 1996; 57: 257– 264Google Scholar

85 Pallanti S, Quercioli L, Paiva RS, Koran LM: Citalopram for treatment-resistant obsessive-compulsive disorder. Eur Psychiatry 1999; 14: 101– 106Crossref, Google Scholar

86 McDougle CJ, Goodman WK, Leckman JF, Lee NC, Heninger GR, Price LH: Haloperidol addition in fluvoxamine-refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study in patients with and without tics. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1994; 51: 302– 308Crossref, Google Scholar

87 Skapinakis P, Papatheodorou T, Mavreas V: Antipsychotic augmentation of serotonergic antidepressants in treatment-resistant obsessive-compulsive disorder: a meta-analysis of the randomized controlled trials. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 2007; 17: 79– 93Crossref, Google Scholar

88 Stamouli S, Lykouras L: Quetiapine-induced obsessive-compulsive symptoms: a series of five cases. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2006; 26: 396– 400Crossref, Google Scholar

89 van Nimwegen L, De Haan L, Van Beveren N, Laan W, Van Den Brink W, Linszen D: Obsessive compulsive symptoms in a randomized double blind study with olanzapine or risperidone in young patients with recent onset schizophrenia or related disorders. Schizophr Res 2006; 81: (suppl) 99– 100Google Scholar

90 Linszen D: Obsessive compulsive symptoms in a randomized double blind study with olanzapine or risperidone in young patients with recent onset schizophrenia or related disorders. Schizophr Res 2006; 81: (suppl) 99– 100Google Scholar

91 Ertugrul A, Yagcioglu AEA, Eni N, Yazici KM: Obsessive-compulsive symptoms in clozapine-treated schizophrenia patients. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2005; 59: 219– 222Crossref, Google Scholar

92 Ongur D, Goff DC: Obsessive-compulsive symptoms in schizophrenia: associated clinical features, cognitive function and medication status. Schizophr Res 2005; 75: 349– 362Crossref, Google Scholar

93 Warneke L: A possible new treatment approach to obsessive-compulsive disorder. Can J Psychiatry 1997; 42: 667– 668Crossref, Google Scholar

94 Koran LM, Aboujaoude E, Bullock KD, Franz B, Gamel N, Elliott M: Double-blind treatment with oral morphine in treatment-resistant obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2005; 66: 353– 359Crossref, Google Scholar

95 Mellman LA, Gorman JM: Successful treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder with ECT. Am J Psychiatry 1984; 141: 596– 597Crossref, Google Scholar

96 Wohlfahrt A: [Successful ECT in obsessive-compulsive disorders: a case report.] Nervenarzt 1996; 67: 397– 399 (German, English abstract)Google Scholar

97 Greenberg BD, George MS, Martin JD: Effect of prefrontal repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in obsessive-compulsive disorder: a preliminary study. Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154: 867– 869Crossref, Google Scholar

98 Mantovani A, Fallon B, Simpson H, Rossi S, Pallanti S, Hollander E, Lisanby S: Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) in the treatment of resistant obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD): clinical outcomes and neurophysiological correlates. Neuropsychopharmacology 2004; 29: (suppl 1) S153Google Scholar

99 Alonso P, Pujol J, Cardoner N, Benlloch L, Deus J, Menchon JM, Capdevila A, Vallejo J: Right prefrontal repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in obsessive-compulsive disorder: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Am J Psychiatry 2001; 158: 1143– 1145Crossref, Google Scholar

100 Mansur C, Bernik M, Cabral S, Myczkowsky J, do Carmo Sartorelli M, Rumi D, Rosa M, Pridmore S, Rigonatti S, Marcolin MA: Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation as adjunctive treatment for resistant OCD: a randomized double blind placebo-controlled trial (preliminary data and interim analysis) [Abstract P02.116, CINP Congress 2006]. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2006; 9 (suppl 1): S195Google Scholar

101 Praško J, Penn.šková B, Záleský R, Novák T, Kopecek M, Bares M, Horácek J: The effect of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) on symptoms in obsessive compulsive disorder: A randomized, double blind, sham controlled study. Neuro Endocrinol Lett 2006; 27Google Scholar

102 George MS, Ward HE, Ninan PT, Pollack MH, Mahas Z, Goodman WK, Ballenger JC: Open trial of VNS in severe anxiety disorders, in 2003 Annual Meeting New Research Program and Abstracts. Arlington, Va, American Psychiatric Association, 2003, number 768Google Scholar

103 Greenberg BD, Price LH, Rauch SL, Friehs G, Noren G, Malone D, Carpenter LL, Rezai AR, Rasmussen SA: Neurosurgery for intractable obsessive-compulsive disorder and depression: critical issues. Neurosurg Clin North Am 2003; 14: 199– 212Crossref, Google Scholar

104 Baer L, Rauch SL, Ballantine HT Jr, Martuza R, Cosgrove R, Cassem E, Giriunas I, Manzo PA, Dimino C, Jenike MA: Cingulotomy for intractable obsessive-compulsive disorder: prospective long-term follow-up of 18 patients. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1995; 52: 384– 392Crossref, Google Scholar

105 Kim CH, Chang JW, Koo MS, Kim JW, Suh HS, Park IH, Lee HS: Anterior cingulotomy for refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2003; 107: 283– 290Crossref, Google Scholar

106 Mindus P, Jenike MA: Neurosurgical treatment of malignant obsessive compulsive disorder. Psychiatr Clin North Am 1992; 15: 921– 938Crossref, Google Scholar

107 Rauch SL, Dougherty DD, Eskandar E, Fischman AJ, Jameson M, Cosgrove GR: PET predictor of OCD response to anterior cingulotomy: replication of findings suggests potential clinical utility [ACNP Annual Meeting 2006 Abstracts]. Neuropsychopharmacology 2006; 31: (suppl 1) S217Google Scholar

108 Nuttin B, Cosyns P, Demeulemeester H, Gybels J, Meyerson B: Electrical stimulation in anterior limbs of internal capsules in patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Lancet 1999; 354: 1526Crossref, Google Scholar

109 Anderson D, Ahmed A: Treatment of patients with intractable obsessive-compulsive disorder with anterior capsular stimulation: case report. J Neurosurg 2003; 98: 1104– 1108Crossref, Google Scholar

110 Abelson JL, Curtis GC, Sagher O, Albucher RC, Harrigan M, Taylor SF, Martis B, Giordani B: Deep brain stimulation for refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder. Biol Psychiatry 2005; 57: 510– 516Crossref, Google Scholar

111 Greenberg BD, Gabriels L, Malone DA, Kubu CS, Malloy PF, Okun MS, Shapira NA, Friehs GM, Nuttin B, Rezai AR, Dougherty DD, Rauch SL, Goodman WK, Rasmussen SA: Deep brain stimulation (DBS) for OCD: effects in multiple domains. Biol Psychiatry 2006; 59: (8 suppl 1) 198SCrossref, Google Scholar

112 Carlyle T: Critical and Miscellaneous Essays: Collected and Republished, vol 1, New York, Hurd and Houghton, 1864, p 462Google Scholar

113 McDonald CJ: Protocol-based computer reminders, the quality of care and the non-perfectability of man. N Engl J Med 1976; 295: 1351– 1355Crossref, Google Scholar

114 Dexter PR, Perkins S, Overhage JM, Maharry K, Kohler RB, McDonald CJ: A computerized reminder system to increase the use of preventive care for hospitalized patients. N Engl J Med 2001; 345: 965– 970Crossref, Google Scholar

115 Nichol KL, Nordin J, Mullooly J, Lask R, Fillbrandt K, Iwane M: Influenza vaccination and reduction in hospitalizations for cardiac disease and stroke among the elderly. N Engl J Med 2003; 348: 1322– 1332Crossref, Google Scholar