The Role of Psychosocial Stress in the Onset and Progression of Bipolar Disorder and its Comorbidities: The Need for Earlier and Alternative Modes of Therapeutic Intervention

Abstract

Psychosocial stress plays an important role at multiple junctures in the onset and course of bipolar disorder. Childhood adversity may be a risk factor for vulnerability to early onset illness, and an array of stressors may be relevant not only to the onset, recurrence, and progression of affective episodes, but the highly prevalent substance abuse comorbidities as well. A substantial group of controlled studies indicate that various cognitive behavioral psychotherapies and psycho-educational approaches may yield better outcomes in bipolar disorder than treatment as usual. Yet these approaches do not appear to be frequently or systematically employed in clinical practice, and this may contribute to the considerable residual morbidity and mortality associated with conventional treatment. Possible practical approaches to reducing this deficit (in an illness that is already underdiagnosed and undertreated even with routine medications) are offered. Without the mobilization of new clinical and public health approaches to earlier and more effective treatment and supportive interventions, bipolar illness will continue to have grave implications for many patients’ long-term well being.

Gene and environment interactions are commonly assumed in the etiology and pathogenesis of recurrent unipolar depression (Caspi et al., 2003; Kendler, Thornton, & Gardner, 2000, 2001). Less well explored is the role of psychosocial stressors in the onset, development, and progression of bipolar disorder; however, considerable evidence exists that supports the view that in bipolar disorder there are a variety of critical junctures at which psychosocial stress may exert profound effects on the onset and course of illness.

Bipolar illness is considered one of the most genetically mediated disorders, yet the role of environment may be markedly underestimated. For example, although there are high concordance rates of bipolar disorder in identical twins, a number of studies suggest that this rate is only approximately 50 to 60%, leaving considerable room for other influences (Allen, 1976; Craddock & Jones, 1999; Kieseppa, Partonen, Haukka, Kaprio, & Lonnqvist, 2004). Similarly, although there is a high incidence rate of bipolar illness in families, about 50% of patients with bipolar illness do not have a positive family history of bipolar illness in first-degree relatives (Leverich, McElroy, et al., 2002; Suppes et al., 2001), again suggesting contributions from other influences. To the extent that bipolar illness emerges as a polygenic disorder (involving multiple gene vulnerabilities, each of small effect), it could be argued that genetic vulnerability also plays a role in those without a positive family history of bipolar illness, that is, individuals who do not have bipolar illness may pass on sufficient mixes of susceptibility genes such that the illness emerges in the next generation (Comings, 1995; Payne, Potash, & DePaulo, 2005).

Yet, the identical twin data noted indicate that this polygenic concept is not an adequate explanation, and it is likely that environmental influences are also very much involved. In this paper we review selected aspects of the literature and present new data from the framework that the quality, severity, repetition, and timing of psychosocial stressors may exert very different influences on the emergence versus progression of both affective episodes and the many comorbidities that are overrepresented in bipolar disorder.

We believe this developmental perspective is not only of theoretical and conceptual interest, but also of clinical therapeutic importance as well. Although there are currently no available therapeutic tools to alter one’s genetic vulnerability, there are multiple opportunities throughout one’s life (both before and after bipolar illness onset) at which important therapeutic maneuvers can be timed to and targeted at the effects of psychosocial stressors. Such interventions could involve not only more traditional secondary and tertiary prevention, that is, after syndrome or symptom onset, but also the possibility of primary preventive measures as well.

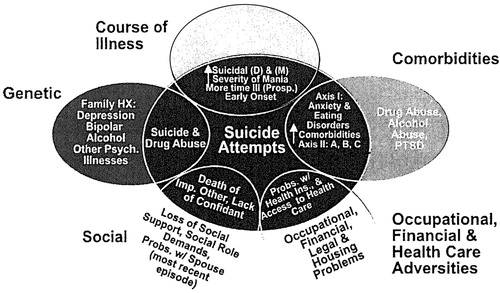

Stress can also play a role in the onset and maintenance of a variety of comorbidities to which bipolar patients are particularly vulnerable. There is, by definition, a fundamental involvement of environmental stressors in the etiology of comorbid posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), but also in the onset, maintenance, and relapse/recurrence of comorbid substance abuse disorders, such as alcohol and stimulant abuse.

Therefore, therapeutic attention directed toward the complex role of psychosocial stressors in the course of bipolar illness and its comorbidities could have a substantial public health impact, and potentially help prevent many of the grave consequences and disabilities associated with bipolar illness. Given the potential positive consequences of such effective intervention, we would hope that this and related papers in this issue help lead to more definitive consensus guidelines for the treatment of bipolar illness within the current health care systems in the United States and in other countries throughout the world. Currently, a positive, prospective, longitudinal, therapeutic approach to the wide array of psychosocial issues typically associated with bipolar illness is relatively underappreciated and underutilized.

Thus, this paper has two main components. The first component is clinical and preclinical data on the role of psychosocial stressors in behavioral neurobiology and the onset and course of bipolar illness. The second is an attempt to outline how to better apply the implications of these data for clinical therapeutics. A series of specific illustrations and suggestions are offered in the hope of more rapidly addressing this area of clinical and public health need in a practical fashion.

Animal models of affective illness and stressors

Preclinical studies in a number of animal species have documented that early life stressors can alter neurochemistry, endocrine responsivity, and behavior in a life-long fashion. The quality, severity, and timing of the environmental occurrences each appear to play a critical role in the eventual change in neurobiology and behavior of the animal (Post, Weiss, Pert, & Uhde, 1987). Single 24-hour periods of maternal deprivation (Levine, Huchton, Wiener, & Rosenfeld, 1991), or 10 days of once-daily maternal separation for 3 hr (but not 15 min), yields an animal with life-long high levels of the stress hormone corticosterone and high levels of anxious behaviors compared with littermate controls (Anisman, Zaharia, Meaney, & Merali, 1998; Francis, Caldji, Champagne, Plotsky, & Meaney, 1999; Meaney, Aitken, Van Berkel, Bhatnagar, & Sapolsky, 1988; Plotsky & Meaney, 1993; Plotsky et al., 2005). For these permanent changes in neuronal and behavioral reactivity to occur, the separation stressors must occur in the appropriate developmental window (or critical period). For example, if the maternal deprivation occurs after the first several weeks of life of the newborn rat pup, these same long-term changes do not occur.

Preliminary clinical data suggest similar contingencies are important in setting endocrine and behavioral reactivity in adult humans based on early life experience. What is not known is how the critical period windows, the quality and severity of stressors, and the role of modifying factors each influence the processes that may occur in the human. As such, one must be careful in extrapolating directly from the preclinical to the clinical condition, although the currently available clinical evidence suggests that there are many human parallels to the preclinical studies.

Early childhood adversity and the subsequent early onset of bipolar disorder

Studies of childhood physical and sexual abuse

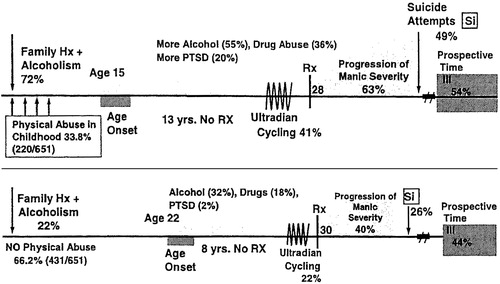

Our studies (Leverich, McElroy, et al., 2002; Leverich, Perez, Luckenbaugh, & Post, 2002; Leverich & Post, in press) and those of others (Brown, McBride, Bauer, & Williford, 2005; Garno, Goldberg, Ramirez, & Ritzler, 2005) have indicated that adults with bipolar illness who had experienced early severe environmental adversity, such as physical or sexual abuse as children, not only had an earlier age of onset of bipolar illness compared with those nonabused, but experienced an overall more serious, complicated, and treatment-resistant course once the illness became manifest.

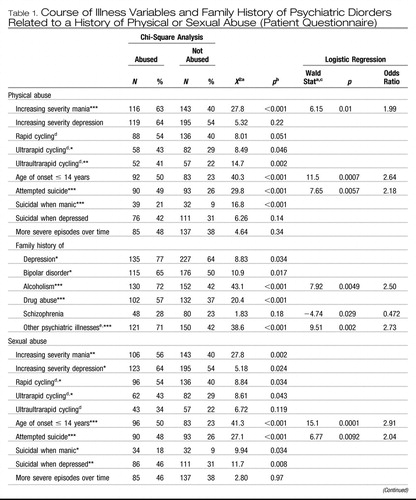

Leverich, McElroy, et al. (2002) investigated 631 outpatients with bipolar I or bipolar II disorder from the Stanley Foundation Bipolar Network (SFBN), focusing on general demographics, a history of physical or sexual abuse as a child or adolescent, course of illness variables, prior suicide attempts, and Axis I and Axis II comorbidities. Prospective ratings were performed on 373 patients who completed at least 1 year of follow-up.

In this study, 185 (49%) of 377 female patients reported experiencing early abuse in childhood or adolescence; 36% reported physical abuse, and 43% reported sexual abuse. Among 274 male patients, 99 (36%) reported being abused in childhood or adolescence; 31% reported physical abuse and 21% reported sexual abuse. The abused group (male and female) had a longer duration of illness at entry into the network, and a longer duration of time ill without treatment. Those patients who reported childhood or adolescent physical or sexual abuse had a higher lifetime prevalence of substance abuse, alcohol abuse, PTSD, and an increased mean number of lifetime Axis I disorders. More patients with a history of either type of abuse had an early age of illness onset (≤ 14 years by patient report) and faster cycling frequencies than patients without abuse. A history of either type of abuse was also associated with an increased incidence of suicide attempts.

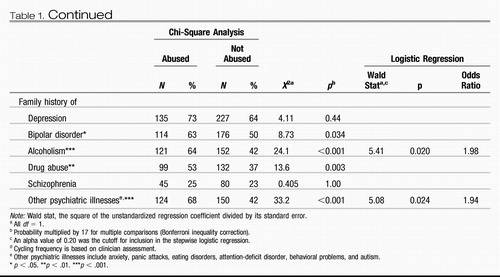

Both the physically and sexually abused groups noted a significantly higher incidence of negative psychosocial stressors before the onset of the first affective episode, as well as before the most recent affective episode. Also, a greater number of co-occurring medical conditions were reported in those who were abused versus those who were not. In the 373 prospectively followed patients, there was a greater severity of illness in the abused compared with the nonabused group as reflected in percentage of time ill during naturalistic treatment.

Two similar studies have been published since the study of Leverich, McElroy, et al. (2002), with many similar findings. Garno et al. (2005) consecutively evaluated 100 patients with bipolar I or II disorder to look for a history of childhood abuse. Almost half of the study group had experienced severe childhood abuse in at least one domain (24% physical abuse, 21% sexual abuse). They found that those patients with a history of severe abuse had a significantly younger age at illness onset, as well as a higher severity level of current manic symptoms, than those without such a history. Analyses indicated significant associations between multiple forms of childhood abuse and the presence of lifetime suicide attempts and a rapid cycling course (four or more episodes per year), and a marginally significant association with comorbid substance misuse or dependence.

Brown et al. (2005) utilized a predominantly male population of patients with bipolar I or II disorder from 11 different sites to study the impact of childhood physical abuse, sexual abuse, and combined abuse on the course of bipolar disorder. As in the other two studies, almost half of all patients reported experiencing some type of physical or sexual abuse. Similar to the results of Leverich, McElroy, et al. (2002), abused patients were more likely than nonabused patients to experience lifetime comorbidities such as PTSD, anxiety disorders, and substance abuse disorders. Brown et al. (2005) did not find an earlier age of onset in any subgroup except for men with combined abuse, and did not find an increase in the number of medical conditions. Rapid cycling was twice as likely in the physically abused group, however.

Variables related to early abuse and bipolar disorder

Age of onset.

Bipolar illness with early age of onset, by itself, appears to be an extremely robust risk factor for an overall adverse outcome (Birmaher et al., 2006; Carlson, Bromet, & Sievers, 2000; Cate Carter, Mundo, Parikh, & Kennedy, 2003; Engstrom, Brandstrom, Sigvardsson, Cloninger, & Nylander, 2003; Ernst & Goldberg, 2004; Othman, Bailly, Bouden, Rufo, & Halayem, 2005; Perlis et al., 2004; Strober et al., 1988; Suppes et al., 2001). This risk factor is readily understandable from a developmental perspective, because the early mood and behavioral dysfunction may interfere with essential aspects of one’s social, relational, and educational roles and opportunities. Tasks at the neural-developmental level, including emotion regulation and modulation and the ability to exert higher levels of cortical and cognitive control over activity in lower centers may be seriously impaired as well.

The observations of illness-related interference with normal development is particularly troubling from the perspective noted here that an early age of onset of bipolar illness is associated with a greater number of years’ delay until first treatment in both outpatient clinical (Leverich & Post, in press) and epidemiological population samples (Wang et al., 2005). Thus, earlier recognition, diagnosis, and treatment of early onset bipolar disorder may alter what otherwise carries a poor prognosis in adolescence and early and late adulthood.

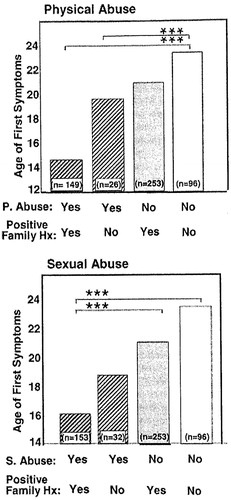

As illustrated in Figure 1, there appear to be potent gene-environment interactions between childhood stressors of physical abuse and sexual abuse and a positive family history of mood disorders (in first-degree relatives) on the age of onset of bipolar illness. Those who have both vulnerability factors have the earliest age of onset, compared with those who have either one or neither (Garno et al., 2005; Leverich, McElroy, et al., 2002). Obviously, in these types of studies, one cannot dissect the role of familial (nongenetic) factors from those relating to specific genetic ones, and here we only imply that the familial association may or may not have genetic determinants.

The important cross-fostering studies of Meaney and associates in rodents (Francis, Diorio, Liu, & Meaney, 1999), as well as the elegant studies of Insel et al. in several animal species (Francis, Szegda, Campbell, Martin, & Insel, 2003; Insel, 1997; Winslow, Noble, Lyons, Sterk, & Insel, 2003) should make one extremely cautious in ascribing what appear to be genetic predispositions to genes, as opposed to familial/environmental influences that can themselves determine lasting neurobiological and behavioral traits. The study of Francis and associates (Francis et al., 2003) indicates that both in utero environmental influences, as well as those in the neonatal environment, may each be important alone and in combination in helping to determine various behavioral and neurobiological characteristics. Traits modified by cross-fostering can be transmitted to the next generation via changes in DNA methylation (Meaney, personal communication, 2005). Tsankova et al. (2006) reported that chronic social defeat stress in mice and chronic treatment with antidepressants induced opposite effects on brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF). Defeat stress downregulated BDNF by repressive histone methylation, whereas chronic imipramine reversed this via increasing histone dicetylation. Thus, chromatin remodeling may provide a basis for lasting effects of stress and their reversal during antidepressant treatment.

As in the preclinical studies, the early occurrence of stressors in humans may in some instances have more profound effects than those occurring later in life. In our clinical sample (Leverich, McElroy, et al., 2002; Leverich & Post, in press), those with trauma in childhood had a more adverse course of illness than those who experienced these traumas only in adulthood.

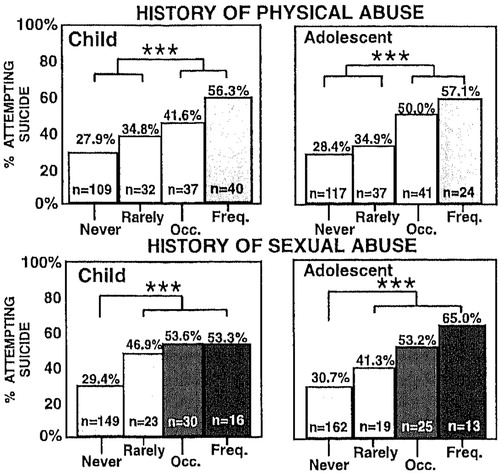

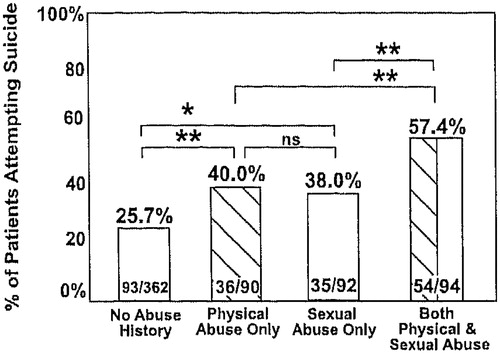

Obviously, the quality of the stressor as well as its frequency and severity may all cumulatively impact short-term and long-term behavioral and biochemical adaptations. There may also be special difficulties if the abuser is within one’s own family (Trickett, Reiffman, Horowitz, & Putnam, 1997), and the usual supportive role of this individual is transformed into one of fear and foreboding. Similarly, in the studies of Leverich et al. (2003; Leverich, Perez, et al., 2002), single or rare instances of physical abuse had a smaller impact on suicidality than individuals who reported experiencing these traumas more frequently (Figure 2, top panels). In contrast, it appears that even rare instances of childhood sexual abuse are associated with a highly significant increased incidence of subsequent medically serious suicide attempts and a “dose”-response relationship is less evident in this domain (Figure 2, bottom left) than in physical or sexual abuse later in life during adolescence (Figure 2, bottom right). Moreover, experiencing both types of childhood adversity increases the incidence of suicide attempts more than either stress alone (Figure 3).

Illness progression.

Those patients with a history of childhood physical or sexual trauma go on to have a more adverse course of bipolar illness compared with outpatients without such an early adverse history. In the studies of Leverich et al. (Leverich, McElroy, et al., 2002; Leverich & Post, in press), this more adverse course was manifest both by self-report retrospectively prior to SFBN entry at approximately average age 40, as well as after SFBN entry, as assessed prospectively. Retrospectively, there were more episodes and a greater degree of cycling in those with early abuse history (Table 1). Prospectively, there was an increased percent time ill in those with early abuse history compared with those without such early abuse histories (Table 2) as well as an increased incidence of medically severe suicide attempts.

Comorbidities.

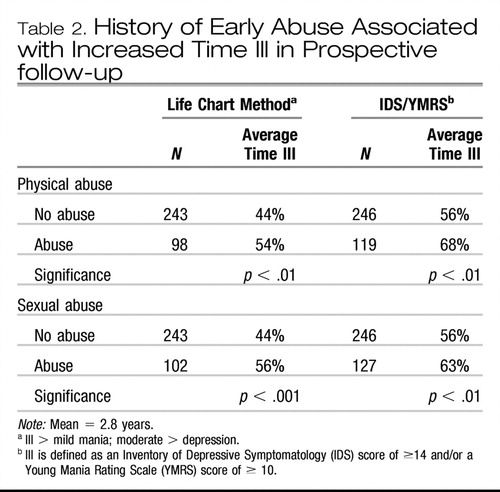

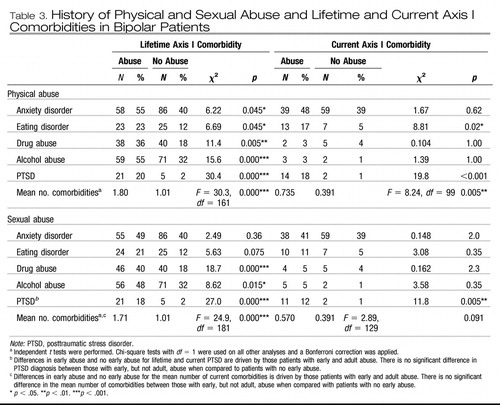

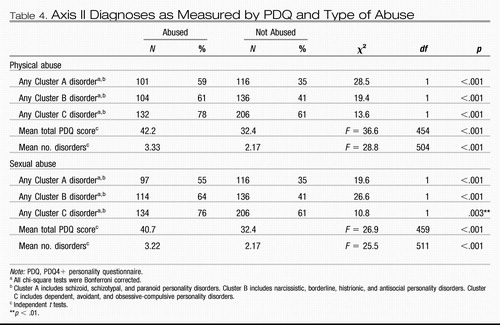

It is striking that those with early environmental adversity (childhood physical or sexual abuse) developed more Axis I, II, and III comorbidities than their comparison clinic members (Leverich, McElroy, et al., 2002; Leverich, Perez, et al., 2002; Tables 3 and 4). There was a higher incidence of anxiety and eating disorder comorbidities as well as substance abuse in those with early abuse. Each of these comorbidities is likely to be consequential in its own right; in several studies, anxiety comorbidity in the context of bipolar illness is in itself a poor prognosis factor (Boylan et al., 2004; McElroy et al., 2001; Simon et al., 2004).

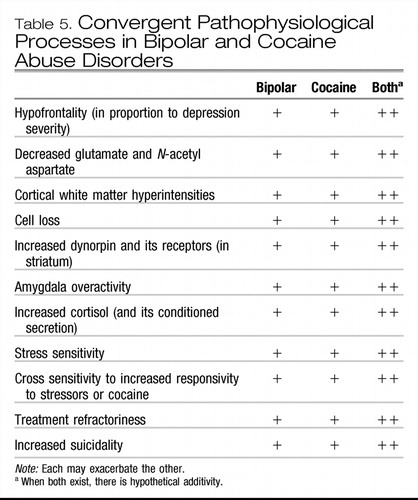

Similarly, comorbid alcoholism and other substance abuse carry a variety of serious risks, not only in the clinical domain, but also based on the fact that stimulant abuse, for example, engenders a variety of neurobiological effects at the level of alterations in gene expression (Post & Weiss, 1988) that appear to interact adversely and either be additive or potentiative with many of the same brain abnormalities associated with bipolar illness (Post, Speer, Hough, & Xing, 2003; Table 5). Thus, it appears that one is adding a new set of neurobiological alterations and vulnerabilities with such substance abuse. Individuals with primary substance abuse are already at a high risk for a generally poor outcome as well as higher degrees of noncompliance and increased risk of relapse. When these risks are combined with the difficulties inherent in bipolar illness treatment, the potential adverse interactions are extraordinary (Krishnan, 2005; Sonne, Brady, & Morton, 1994; Strakowski, DelBello, Fleck, & Arndt, 2000).

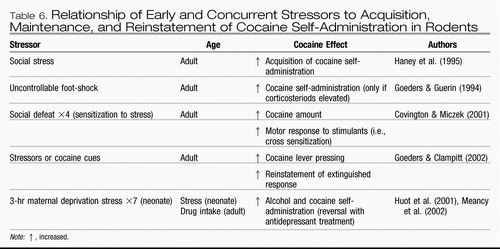

Severe stressors (such as those described here) may thus play a unique role in the vulnerability to the onset of bipolar illness itself and the onset of substance abuse comorbidity. In addition, it also appears likely that stressors in adulthood can influence either type of relapse, that is, into new affective episodes in those who are in relatively stable remission and into renewed substance abuse in those who have been abstinent. The preclinical data in animals strongly support the idea that early stressors may convey a life-long vulnerability to subsequent alcohol or other substance abuse compared with littermate control animals that do not experience these stressors (Huot, Thrivikraman, Meaney, & Plotsky, 2001; Meaney, Brake, & Gratton, 2002; Table 6). In some instances, the differential effect of stress as a function of degree of control over the stressor is also apparent in the subsequent adoption (or not) of substance self-administration as an adult.

Impact on future stressors.

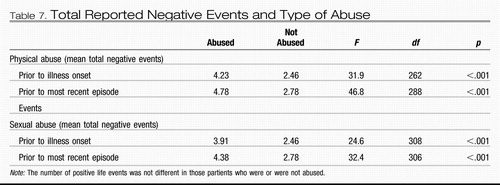

The occurrence of early childhood physical or sexual abuse also appears to be associated with an increased occurrence of negative (as opposed to positive) life events in adulthood (Leverich, McElroy, et al., 2002; Table 7). This increased incidence of stressors in those with the experience of early adversity is subject to a variety of interpretations.

One interpretation is that the early occurrence of adversity may put an individual at increased risk for exposure to negative situations and negative outcomes, that is, the accumulation of negative life events. This risk appears to be selective to the occurrence of later negative life events, as the number of later positive life events is equal in those with, versus without, early adversity (Leverich, McElroy, et al., 2002).

The increased number of adverse life events in adulthood reported by people who were abused early in life confounds the interpretation of whether there is stress sensitization or not, that is, increased reactivity to stressors later in life. Considerable evidence in unipolar depression supports stress sensitization, particularly over the first several episode occurrences (Kendler et al., 2000, 2001). It is postulated that following the occurrence of sufficient numbers of “triggered” affective episodes, lesser degrees of stress, the anticipation of stress, or even a lack of stress could still be associated with later episodes (Post, 1992). Thus, if stress sensitization were occurring in the context of an increasing number of negative life events, the individual might be at particularly increased risk of having a subsequent episode based both on the number of stressors and their increased likelihood of triggering an episode when they do occur, that is, the sensitization effect (Post, 2004c; Post, Ketter, Speer, Leverich, & Weiss, 2000). The occurrence of stressors in patients late in their course of episode recurrence cannot be used to refute the stress sensitization hypothesis; evidence against it would be derived from the observation that stressors did not increase the risk of subsequent episodes compared with periods of time without stressors.

Treatment resistance.

Not only is there an increased number of episodes and overall morbidity observed in the retrospective course of illness in those with early adversity compared with those without, but also this continues prospectively. When these patients were treated naturalistically by experts in the field, either with monotherapy or with a wide range of treatment modalities in complex combination (Kupka et al., 2005; Nolen et al., 2004; Post et al., 2003), they appeared to be less responsive to this prospective treatment, as rated by clinicians, compared with those without such adversity (Leverich, McElroy, et al., 2002). This is particularly important in the area of increased duration of time depressed compared with time euthymic.

It is also clear that there are multiple potential contributors and confounds to this less favorable outcome because those with early adversity have an earlier age of onset, more prior episodes, and more comorbidities, each of which themselves have been associated with a generally more adverse course of illness. Although it may be possible to statistically correct for these highly intercorrelated events and diverse impacts, it is equally possible that from a clinical perspective, it is the accumulation and interaction of these multiple adverse risk factors (including familial history, stressors, earlier onset, greater number and faster recurrence of episodes, and more anxiety and substance abuse comorbidity) that lead to increasing vulnerability to episode recurrence and general treatment resistance. It is likely from a clinical, if not statistical, perspective that attempting to prevent or reduce the impact of one or more of these factors (i.e., early adversity, more stressors, more episodes, or more comorbidities) may eventually be important in helping patients achieve better outcomes.

Stressors at the onset of illness and the progression of affective episodes

Suicide attempts

If one assumes that a history of having made a medically serious suicide attempt is a marker of not only a future risk of suicide, but also of (as we have found) a more serious course of affective illness (Leverich et al., 2003), then a wide range and variety of psychosocial stressors in adolescence and adulthood appear significantly associated with such an act and its associated outcome. Having made a medically serious suicide attempt prior to SFBN entry was a marker for a more adverse course of prospective illness as assessed by clinician ratings of increased duration of time ill and increased severity of depression. A suicide attempt prior to SFBN entry was associated with an array of factors such as loss of social support, and others that could put the patient at an increased risk of not having potentially stress-modifying support from others (Fig. 4).

For example, not having a close friend or confidante or being unmarried are risk factors for a serious suicide attempt, as are general and specific financial characteristics, including not only lower income but also a lack of adequate health insurance and health care access. These two factors are notable because those patients with serious suicide attempts have a greater need not only for psychiatric treatment but also for access to general medical care because they have more Axis III medical comorbidities. When this needed medical access is absent, it can be additionally demoralizing and perhaps contribute to one’s hopelessness and suicidality (Fig. 4).

These types of retrospective data associated with a lack of psychosocial support and increased suicidality parallel other markers of poor prospective outcome in children with bipolar illness treated naturalistically in the community (Geller et al., 2002; Geller, Tillman, Craney, & Bolhofner, 2004). In these patients, Geller et al. (2004) found that a lack of an intact family and a lack of maternal warmth were both associated with an increased risk for earlier relapse.

Similarly, the epidemiological data of Kessing, Agerbo, and Mortensen (2004) indicate that the loss of a family member by suicide is a stressor significantly associated with the onset of a first manic episode. In that study, the onset of a manic episode appeared to be specifically related to death by suicide and not by other medical causes, and the suicide of either a mother or sibling was a greater risk factor for a subsequent manic hospitalization than suicides by other relatives and family members. These data not only point to some specificity in psychosocial stressors precipitating manic episodes, but also the possibility for familial influences (both genetic vulnerability for bipolar illness and suicide and the added environmental vulnerability of having lived with this ill individual) interacting with the immediate environmental stressor (i.e., the death of a loved one and the subsequent funeral). Ambelas (1979) and others (Ranga, Krishnan, Swartz, Larson, & Santoliquido, 1984) have also found that attending a funeral could be a trigger for mania.

Gender differences in vulnerability to stressors

Unipolar depression.

Kendler and colleagues (Kendler, Myers, & Prescott, 2005; Kendler, Thornton, & Prescott, 2001) have described gender differences in the types of stressors that appear particularly pertinent in the occurrence of unipolar depressive episodes. These investigators found that losses in the area of a woman’s social network and support system were particularly pertinent to depression onsets. In contrast, job-related difficulties and divorce or separation appeared to be particularly pertinent for depression onset in men. Other factors for women included an increased incidence of housing problems, loss of a confidante, and illness in women in one’s social network. Men also had an increased incidence of job loss, legal problems, and robbery.

Bipolar disorder.

Based on patient questionnaire data (Leverich, Perez, et al., 2002), we had the opportunity to explore gender differences in psychosocial stressors. The stressors were rated at two different time points in the illness. The first time point, at illness onset, obviously involves a great deal of potential memory obfuscation based on the long duration of recall necessary for these adults who, at SFBN entry, were on average 40 years old with a duration of illness of about 20 years. However, at the second time point, stressors were rated in relationship to the onset of the most recent episode, which would involve much more immediate recall and therefore much less chance for inaccuracy.

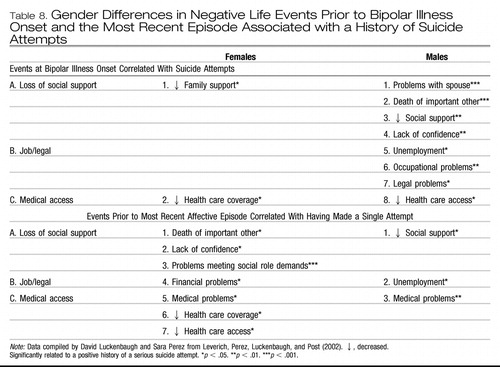

There were interesting gender differences at both illness onset and the most recent episode in the types of stressors that were significantly related to making a suicide attempt (Table 8). Men who made suicide attempts (compared with those who did not) experienced a wide variety of negative life events including four in the category of loss of social supports, three in the area of job and legal difficulties, and one in medical and health care access, particularly at the time of bipolar illness onset.

In contrast, in females who made a serious suicide attempt, there were fewer stressors at illness onset, but many more prior to the last affective episode before SFBN entry. This suggests the accumulation of many psychosocial stressors that were significantly related to making a serious suicide attempt and generally occurred after illness onset and became more problematic prior to the last affective episode. Of interest, the development of difficulties in the area of meeting mul social role demands (prior to the most recent episode) was highly significantly related to women (but not men) with bipolar illness having made a suicide attempt. Others in the areas of (a) loss of social supports; (b) financial problems; and (c) medical problems, health care coverage, and access were also (but less significantly) related to women having made a suicide attempt.

In contrast, in men, a host of negative environmental events were already involved, even at illness onset in those who would subsequently make a suicide attempt. Thus, the data in Table 8 suggest that the buildup of multiple stressors during the illness could relate to suicide attempts in women, while men who subsequently made suicide attempts had these stressors and negative life events even before the illness started.

Because no Bonferoni corrections were applied in this exploratory analysis, these data remain to be further replicated and confirmed in other studies. Nonetheless, they suggest the likely possibility that the impact of different kinds of psychosocial stressors associated with bipolar patients making a serious suicide attempt may be, in part, gender related, both at illness onset and in those preceding the most recent episode. As having made a serious suicide attempt is itself a marker of a more severe course of bipolar illness as noted above, many of these stressors could also reflect vulnerability to illness progression.

The data on the most recent episode are also of interest in relation to the general findings in the literature that episodes later in the illness are likely to be more spontaneous, whereas earlier episodes are likely to be triggered by psychosocial stressors. From the stress sensitization perspective (Post, 2004c; Post et al., 2000, 2003; Post, Leverich, Xing, & Weiss, 2001; Post, Weiss, Leverich, Smith, & Zhang, 2001), when stressors do occur in later episodes, there is increased vulnerability to stressors of small magnitude, or hypothetically, as suggested by Kraepelin (1921), even those that are just anticipated. In this regard, the findings may suggest the importance of building support networks for prevention of episode recurrence as well as suicide attempts in women, while in men, employment, legal, and medical adversities, in addition to loss of social supports, may be more important targets for therapeutic intervention, even from the first onset of illness. Many of these same factors may also have an impact on the occurrence of comorbidities. As outlined in Table 5, stressors can both predispose to the adoption of problematic substance abuse and also be involved in precipitating relapses in those who have abstained. It is noteworthy that women with bipolar illness are seven times more likely to suffer from alcohol abuse than women in the general population (Frye et al., 2003).

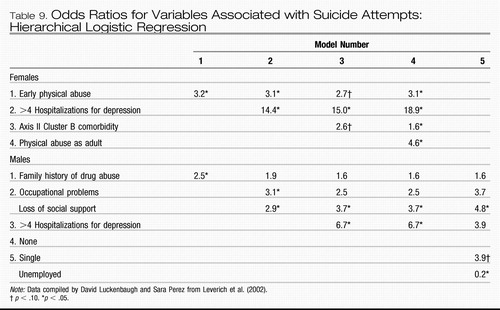

Hierarchical logistic regression, using all of the variables that were significantly related to suicide attempts in the univariate analysis in the entire patient group, also identified these different variables separately in women and in men that added a significant odds ratio for making a suicide attempt (Table 9). In women, a history of early abuse remained a significant risk factor initially after all of the other variables were entered in Models 2– 4. More than four hospitalizations for depression, Cluster B Axis II comorbidities, and physical abuse as an adult, as well as problems meeting multiple social role demands, were also risk factors for a suicide attempt.

Conversely, in males, a family history of drug abuse, occupational problems, and loss of social support showed significant odds ratios for the risk of a suicide attempt. Only having greater than four hospitalizations for depression was a common risk factor for suicide attempts in both men and women, but with a substantially higher odds ratio for women than for men.

Overcoming obstacles to achieve optimal illness intervention and prevention

General treatment obstacles

Given this background on the critical role of psychosocial stressors and their adequate management to the long-term course of bipolar illness, one can begin to envision more ideal approaches and strategies than those that are currently routinely practiced. Physicians and family members need to closely monitor those individuals at a high risk for affective disorders because of a positive family history, in much the same way that a very high risk for breast cancer, hypertension, and myocardial infarction (MI) is monitored. Families and physicians do not do as well in the domain of depression and bipolar illness as they often do for those other illnesses (Das et al., 2005; Hirschfeld, Cass, Holt, & Carlson, 2005).

Stigma continues to be a potent force in psychiatric illness and diagnosis, often yielding huge delays to treatment onset even in the face of quite severe symptomatology (Barney, Griffiths, Jorm, & Christiensen, 2005; Hinshaw & Cicchetti, 2000). This treatment gap could be remarkably shortened in those at high risk by an awareness of developmentally pertinent symptoms and appropriate evaluation and treatment where necessary. One should rationally assess the fears of stigmatizing an individual with a psychiatric diagnosis, which often contributes to the delays in evaluation and treatment. These fears should be balanced against the fact that early-onset bipolar illness itself carries a very high risk for a poor outcome (Birmaher et al., 2006; Geller et al., 2004; Leverich & Post, in press; Perlis et al., 2004). In those at a high risk by virtue of a positive family history or adverse childhood life events, the “reverse stigma” of not recognizing and treating affective episodes appropriately and promptly may have life-long and even life-threatening consequences.

It appears that clinical investigators sufficiently understand some of the pathophysiological and therapeutic aspects of unipolar and bipolar affective illness, so that maneuvers aimed at primary prevention in those at highest risk could be considered, similar to those used in other medical illnesses. For example, in presymptomatic individuals with a family history of very early onset breast cancer, not only does one monitor more closely, but also in some instances active presymptomatic treatment is instituted with tamoxifen or, in those at highest risk, even prophylactic bilateral mastectomies are considered. Preventive treatment is particularly evident when one addresses risk factors such as hypercholestremia, hypertriglyceridemia, obesity, hypertension, and platelet clotting in the hope of avoiding a first or recurrent MI. Parenthetically, depression is also a major risk factor both for having an MI and for dying from it; depression should be as aggressively treated as the other risk factors noted above (although it usually is not, and often depression is not even on the typical list of such risk factors, i.e., the American Heart Association).

Contrary to general opinion (and even assumptions among many practicing clinicians), one could now in a preliminary fashion roughly quantitate the degree of risk for psychiatric illness so that appropriate monitoring and intervention (like that described above for preventing an MI) can be employed in a more timely fashion. This can presently be done (as described below), even without the knowledge of a series of genetic risk factors that are (and will rapidly further be) emerging from a patient’s profile of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs; Cox, 2004). When SNP profiling becomes better able to characterize affective illness vulnerability and predict individual treatment response to specific pharmacological agents, it will even further enhance the risk-benefit assessment of early intervention and prevention strategies.

Known and partially quantitated risk factors for affective illness

Bilineal positive family history.

In the case of a bilineal (both parents) positive family history for affective illness (with at least one parent bipolar), that is, a high genetic and familial risk, there is an approximately 70% chance that the offspring of these parents will develop a unipolar or bipolar affective disorder over their lifetime (Gershon et al., 1982; Lapalme, Hodgins, & LaRoche, 1997). In the context of this extraordinarily high risk, it would appear warranted to begin to intervene at the first appearance of subthreshold symptoms even before the onset of a full diagnosis. Such early intervention would not be primary prevention, that is, presymptomatic, but such secondary prevention would be a more conservative threshold for considering treatment in those at highest risk because of a bilineal positive family history.

Without formal studies, clinicians and family members seeking such early interventions at the point of emerging symptoms not meeting full diagnostic thresholds would be doing so in the absence of good data in the hope that a proven agent for treatment of a full-blown episode would also be effective in the initial stages of illness development and prevention. This may or may not prove to be a valid assumption. For example, it had been assumed that the highly effective antiseizure drug phenytoin would prevent the development of seizures following neurosurgery or head trauma, yet repeated controlled studies have indicated that this is not the case, and other drugs needed to be explored for this purpose of primary prevention or antiepileptogenesis (Temkin, Jarell, & Anderson, 2001). In parallel in the laboratory, phenytoin, carbamazepine, and lamotrigine do not work for the early prevention of the development of full-blown amygdala-kindled seizures in animals, whereas valproate, diazepam, and levetiracetam are effective in both the early and the middle full-blown phases (Post, 2004a).

Such pharmacological dissociations are likely to occur in the realm of the early development (prevention) versus acute treatment of a full-blown affective episode as well, although one cannot assume that the therapeutic profile of a drug would carry over from kindled seizures to affective illness. Lithium, which is effective in full-blown affective episodes, lacks efficacy in any stage of amygdala-kindled seizure evolution. Ultimately, for the prevention of the development of full-blown affective episodes, only empirical data will suffice. Such data will not be available for many years because these types of studies in bipolar illness have not yet been initiated (as they have been already for many years in schizophrenia; Post & Kowatch, 2006).

Childhood adversity and a positive family history of affective disorder.

Childhood adversity (such as physical or sexual abuse) and a positive family history of affective disorder, either as sole risk factors or combined risk factors, yield a highly significant earlier onset of bipolar disorder (Figure 1) compared with those without these vulnerability factors (Garno et al., 2005; Leverich, McElroy, et al., 2002; Perlis et al., 2004). Given the strong inverse relationship between the age of illness onset and the time delay until first treatment (Leverich, McElroy, et al., 2002; Leverich & Post, in press; Wang et al., 2005), early evaluation of the troubled child with these dual risk factors would appear indicated.

Family history of suicide.

The genetics of suicide can run parallel to or separate from the genetics of primary affective illness. As such, a positive family history for suicide appears to be an independent risk factor. Recent study data indicate that the children of parents who have made a suicide attempt have a sixfold increased risk of making an attempt themselves (Brent et al., 2002). It is interesting that in that study familial transmission of suicide attempts was more likely if (a) the adult probands had a history of sexual abuse or (b) the offspring were female and had a mood disorder, substance abuse disorder, increased impulsive aggression, and a history of sexual abuse.

In a more recent study, of the probands with mood disorder who had attempted suicide 23.2% had a first-degree relative with a history of suicidal behavior compared with 13.2% in the families of nonsuicidal individuals. Rates of reported childhood abuse and severity of lifetime aggression were also higher in probands with a family history of suicidal behavior (Mann et al., 2005). Therefore, it would appear appropriate to give special attention to the affectively troubled individual with a positive family history of suicide or suicide attempts.

Current parental affective illness.

When a child’s parent has an affective illness, especially depression in the mother, depending on the age of the child and the associated psychological and social support from other individuals in the family, there may be a substantially elevated risk of affective illness and other psychiatric diagnoses of the children in the family (Klein, Lewinsohn, Rohde, Seeley, & Olino, 2005; Rohde, Lewinsohn, Klein, & Seeley, 2005). Similarly, the presence of postpartum depression or psychosis is a considerable risk factor for a difficult outcome not only in the current newborn, but potentially in the other children in the family as well (Bonari et al., 2004).

Active parental substance abuse and PTSD.

Drug or alcohol abuse in one of the parents also places the children at considerable increased risk both for affective disorders, as well as for a variety of externalizing behaviors. Particularly when parental substance abuse is combined with any of the risk factors noted above, there may be added risks for the child for affective and other disorders (Strakowski et al., 2000). A number of studies have also indicated that the parental presence of PTSD is associated with an increased risk of this disorder in the offspring (Davidson, Tupler, Wilson, & Connor, 1998; Yehuda, Halligan, & Bierer, 2001).

Other comorbid psychiatric diagnoses in children at risk.

Clearly, the occurrence of PTSD in a child should lead to early assessment and potential intervention. A variety of other anxiety disorders may be comorbid with or precursors to affective disorders, and when primary anxiety disorder diagnoses are present, the child deserves careful evaluation (Harpold et al., 2005). As noted previously, the comorbid presence of an anxiety disorder in an adult with bipolar illness places that individual at increased risk for a poor outcome compared with those without an anxiety disorder (Boylan et al., 2004; Henry et al., 2003; Simon et al., 2004).

Several other risk factors could be enumerated, but this brief list should be sufficient to indicate some of the already known risk factors and predictors of subsequent childhood and adult affective disorders. The high odds ratios for the development of affective illness and associated later difficulties suggest the clinical importance of considering early specific therapeutic and preventive measures in those at high risk.

Implications for therapeutics

The data reviewed here about the potential role of psychosocial stressors in the early onset and progression of both bipolar illness and its comorbidities (Figure 5) suggest a wealth of opportunities for therapeutic intervention at the level of both primary and secondary prevention. Considerable data support the use of a variety of psychotherapeutic and psychoeducational programs in not only changing attitudes about bipolar illness, but also in achieving overall better illness outcomes.

Psychosocial interventions

The efficacy of the many different types of psychosocial interventions for bipolar disorder compared with a variety of other circumstances (most typically, treatment as usual) in randomized, controlled clinical trials are reviewed in this volume and in detail by others (Colom & Lam, 2005; Miklowitz, George, Richards, Simoneau, & Suddath, 2003; Otto & Miklowitz, 2004; Otto, Reilly-Harrington, & Sachs, 2003; Scott, 2001). This literature suggests a potent role not only for individual cognitive and behavioral psychotherapeutic approaches to interpersonal conflict and stress management, but also a critical role for general illness and treatment education of both patients and family members (Miklowitz et al., 2003; Pavuluri et al., 2004).

Psychoeducation typically includes better illness awareness and, importantly, daily symptom monitoring (Leverich & Post, 1996, 1998; Miklowitz, 2002), particularly for the beginning of symptom breakthroughs that may herald the onset of a more severe episode. At the same time, approaches to management of the stressors that may be particularly pertinent to an individual’s vulnerable areas are also emphasized (Colom et al., 2003; Vieta & Colom, 2004).

Of interest, although the strength of this literature on controlled psychotherapeutic interventions often exceeds that of many experimental psychopharmacological manipulations that are widely used and justified on the basis of highly preliminary evidence, the data on psychotherapeutic and psychoeducational approaches appear to be less widely applied and accepted, and are even interpreted much more conservatively by the authors and proponents of these studies (Scott, 2001; Vieta & Colom, 2004; Vieta et al., 2005). Caveats about the preliminary nature of the conclusions and the need for further specification of the critical components of therapy mediating a positive outcome are noted, but should not be used to downplay the immediate need for more systematic clinical application of existing approaches. Although in need of extension and specification, the findings are already sufficiently robust to justify the recommendations that these modalities be used more consistently and be included in a more concerted fashion in treatment guidelines.

Psychoeducation.

Illness education and management have become an integral part of the therapeutics of managing child- and adolescent-onset diabetes, with the view that careful monitoring and patient participation are crucial to maintaining good control of glucose levels and subsequently having a beneficial effect on long-term prognosis (Weinzimer, Doyle, & Tamborlane. 2005). These educational and monitoring processes were widely utilized both before and after the recent definitive evidence that such tight regulation did lessen late-life sequellae such as MI. It would be almost inconceivable that a diabetes patient would receive medication and only a perfunctory set of instructions about injecting oneself with X, Y, or Z doses of insulin and coming back to see the physician in a few months. Yet, parallel limited illness education and instructions too often are given in the treatment of a first or later episode of bipolar illness. It is disappointing that, even after a more serious episode requiring hospitalization for mania or for depression because of suicidality, postdischarge follow-up instructions are often similarly lacking in substance, detail, reinforcement, and ongoing modification as new data on the degree and completeness of an individual’s clinical response become available.

Given the data on the role of psychosocial stressors in the precipitation and progression of both bipolar illness and its comorbidities and the data supporting the superiority of systematic psychotherapeutic and psychoeducational approaches compared with treatment as usual, a compelling argument at present can be made for enhanced therapeutic maneuvers specifically aimed at these variables (Scott & Colom, 2005).

Building a medical team and support network.

The task of building a medical team and support network has been expertly enumerated by Miklowitz (2002), and should become essential reading for every patient with bipolar disorder and his or her family members. Inherent in this process is the development of a careful longitudinal monitoring strategy, such that small symptom variations can directly feed back into therapeutic decisions, not only for modified psychopharmacological interventions, but also for additional psychotherapeutic ones as well. We have found that a global or cursory assessment of one’s mood status is not a sufficient means of monitoring the details of an individual’s course of illness that may fluctuate widely in a much higher percentage of patients with bipolar illness than had previously been surmised.

Daily charting of mood

Based on careful but widely spaced assessments, the extent of mood alterations that occur within a patient within weeks or within several days is usually underestimated (Kupka et al., 2005; Nolen et al., 2004; Post et al., 2003). Approximately 42% of carefully assessed bipolar outpatients in the SFBN reported a history of rapid cycling, and in the first year of prospective follow-up, 38% of patients had confirmation of at least four episodes per year despite intensive treatment. More remarkable was the report that 18% of patients had ultrarapid cycling, that is, four or more episodes within a month, and some 19% reported ultra-ultrarapid (or ultradian) cycling in which major mood fluctuations occurred one or more times within a 24-hr day (Kupka et al., 2005; Leverich et al., 2003). We cite these data as further evidence that this large group of patients require careful (preferably daily) prospective record keeping of their mood fluctuations.

For the young child, daily mood charting must of necessity be done by a parental or other caretaking figure, but most older individuals can readily manage daily self-ratings. We recommend the National Institute of Mental Health Life Chart Methodology (NIMH-LCM) as an easy to use format and one that has both a capacity for both self-rating, and rating by others or clinicians in parallel (Leverich & Post 1996, 1998). The NIMH-LCM also has a modified version for symptomatic description of excited activated behaviors versus inhibited and depressive ones in children, in whom accurate characterization of behavior may be crucial to both acute and long-term management. Particularly given the high incidence (Leverich et al., 2003; Leverich, McElroy, et al., 2002; Perlis et al., 2004) but considerable ongoing controversy about diagnostic thresholds (Post & Kowatch 2006), the kiddie LCM (K-LCM) rating of symptom severity based on its degree of associated dysfunction (without taking an arbitrary position on diagnostic category) may be especially important for precise longitudinal monitoring of affective and comorbid symptomatology and its response to treatment.

Development of early warning systems and intervention drills

Such an ongoing daily assessment by the patient or parent provides a tool for evaluating drug and psychotherapeutic interventions on a much more precise and targeted time frame. Such careful monitoring provides that basis for developing an early warning system (EWS) pertinent to each individual (Post & Altshuler, 2005; Post, Speer, & Leverich, 2006). In child or adult instances of symptom breakthrough, specific degrees of altered mood or sleep are specified in advance that will trigger actions ranging from dose modifications, calls to the physician or therapist, or related therapeutic maneuvers. Such monitoring and EWS approaches are routine in diabetes and blood pressure monitoring, for example.

These EWS efforts are like smoke alarms, directed at maintaining a remission and attempting to avoid more major manic or depressive episode occurrence in which immediate intervention is needed on an emergency basis. As part of a full-fledged fire drill for such an emergency, the patient and family members should know the typical characteristics of such an occurrence, whom they should contact, and where they can take the patient for immediate treatment.

Similarly, cognitive and behavioral approaches should be specifically targeted to issues of medication compliance (adherence). In most serious medical conditions, noncompliance is highly prevalent and markedly underestimated. We know this is also the case in bipolar illness in which both manic and depressive mood states themselves further increase the likelihood of not only missed doses, but ceasing taking medication altogether (Keck et al., 1996). Basco and Rush (1996) deal very effectively with many of these compliance issues.

Therapeutic approaches to reducing the impact and consequences of stressors

Coping strategies.

Equally important is an active approach to stress anticipation and management. We know from studies in animals that profound behavioral and neurochemical consequences greatly depend on the “psychological” constructs inherent in the experimental paradigm. That is, an animal given control over the ability to terminate a shock stress does not acquire the same helplessness syndrome or neurochemical abnormalities as its yoked control animal that receives precisely the same amount of physical stressor (Seligman & Beagley, 1975).

Cognitive and behavioral psychotherapy.

Cognitive and behavioral psychotherapy is well suited for helping patients achieve a greater degree of control and, in the process, learning a variety of long-term coping strategies. The data in both unipolar illness, as noted by Fava and colleagues (2004), and an emerging literature in bipolar illness (noted above), also strongly support the importance of such approaches for a variety of positive therapeutic endpoints, including better relapse prevention.

Interpersonal psychotherapy.

In a related fashion, interpersonal psychotherapy, although less systematically tested in bipolar compared with unipolar illness, has much face validity in dealing with issues of job stress and discord within one’s social network which (as seen above) are important precipitants of both initial affective episodes and their recurrences.

Type of education as a function of stage of illness.

We have discussed the possibility that one should specifically tune the nature of the psychotherapeutic and pharmacotherapeutic interventions to the stage of illness that one is attempting to alter. Ongoing psychoeducational efforts would appear to require modification as a function of stage of illness evolution, severity of symptomatology, and an individual’s basic knowledge or ignorance of the illness, its psychopharmacology, and stress management techniques.

Education about the acute management of a full-blown acute manic or depressive episode must necessarily differ from the educational efforts aimed at monitoring and maintaining a remission. The nuances of self-monitoring and the details of a variety of psychopharmacological approaches that may be required in the management of bipolar illness can be daunting, and would appear to require an ongoing and evolving psychoeducational effort (Post & Leverich, in press). For the vast majority of patients with bipolar illness, this cannot be accomplished in a 20-min medication management visit on a monthly or less frequent basis. More time needs to be allotted to the endeavor and, as needed, supported and enhanced by other clinical members of the treatment team.

Type of therapy as a function of course of illness: Representational versus habit memory.

More dynamic and interpersonal psychotherapeutic techniques may be pertinent to initial phases of illness when stressors are intrinsically involved, but in the patient who has developed episode automaticity, other approaches would appear indicated. This transition to more spontaneous episode occurrence might be somewhat similar to the transfer of learning and memory mechanisms from those that are associative or declarative and dependent on amygdala and hippocampal systems of the medial-temporal lobe (representational memory), to those involving repeated learning and training where the memory trace appears to reside in neostriatal and, potentially, cerebellar systems (putatively mediating habit memory; Mishkin & Appenzeller, 1987). When affective episodes begin to occur on a more automatic basis, there may be a similar transition in the neural structures mediating their occurrence in a fashion parallel to the transition from representational to habit memory mechanisms.

Such a transition appears to occur in the area of substance use and abuse as well. For example, in psychomotor stimulant administration, the amygdala is crucial for initial associative aspects of environmental context-dependent behavioral sensitization after one high dose of cocaine (Post et al., 1987), but after multiple high doses of cocaine, the amygdala is no longer required and the nucleus ↑ accumbens and other neural substrates appear to become more intimately involved in the behavioral sensitization process.

This type of transition in the processes and neural structures mediating behavioral sensitization perhaps parallels the clinical difficulties in deconditioning cues associated with relapse to active substance abuse. After a period of acute abstinence a patient may cognitively assume and feel that they are “immune” from associative cues triggering a craving for cocaine or other psychomotor stimulants, but in actuality, they continue to show autonomic and other unconscious reactions to presentations of drug-related cues and related stressors (Childress, McLellan, Ehrman, & O’Brien, 1988; O’Brien, Childress, McLellan, & Ehrman, 1992). Their relapse into active drug use in the face of minor cues or stressors may appear automatic and not even have an active cognitive component, catching them unaware as well.

In this situation of increased automaticity, it would also appear that different techniques, that is, ones that are systematically practiced and overpracticed, are required to further desensitize these now ingrained responses to drug-related cues. Knowing a specific and practical range of behaviors useful in overcoming such breakthrough cravings is of further aid in preventing relapse (Childress, McLellan, Ehrman, & O’Brien, 1987; O’Brien, Childress, McLellan, & Ehrman, 1993). We would submit that dynamic psychotherapies are not as appropriate for this late stage of cocaine relapse prevention as more systematic and practice-based techniques aimed at modifying the habit memory system, including those developed in 12-step programs or similarly constructed therapies. Also, psychotherapeutic work may need to proceed from mourning the loss of the “well self” at the onset of a first bipolar episode to a reevaluation and appropriate setting of short- and long-term goals in the mid phase of illness, to perhaps existential and related psychotherapeutic techniques for a late stage of illness wherein one has to adapt to certain residual problems and disabilities that may no longer be treatment responsive.

A special caveat is warranted in relation to this last point, however. We have repeatedly seen that patients who are apparently al a late and refractory stage of their illness can achieve surprising and often dramatic degrees of clinical improvement once the appropriate therapeutic regimen is instituted. This also appears to be true for patients who appear to have life-long problems with anxiety or PTSD comorbidities, apparent Axis II personality disorders, or associated “character” traits; these can at times almost “magically” disappear when mood and behavior are adequately stabilized with the appropriate psychopharmacological and therapeutic regimens. Thus, it benefits both patient and therapist to continue to assume that notable therapeutic progress is possible at virtually any stage of illness evolution or severity of manifestation.

Here, it is also important to reemphasize the point that the notions of kindling and sensitization that apply to the untreated or inadequately treated illness (Post, 1992, 2004c; Post et al., 2000) do not imply that cycle acceleration, automaticity, and treatment resistance are progressive or invariant outcomes as some have misinterpreted the theory and predictions of outcome. Specific types of treatment can almost always be applied to the manifest illness, although it may take increasingly complex and more heroic measures later than earlier in illness evolution (Frye et al., 2000).

Moreover, patients often come to a psychopharmacological consultation with the statement that they have tried all of the drug approaches to bipolar illness, when in reality they have had only preliminary and cursory exploration of the very wide range of agents now available. This increasingly wide range of therapeutic options for both the primary and comorbid conditions needs to be dealt with in the appropriate psychoeducational framework without overpromising immediate therapeutic benefit or ultimate symptom remission. For example, a drug such as topiramate, which is not effective in the treatment of acute mania in adults, may nonetheless be helpful in comorbid alcohol use, cocaine use, PTSD, eating disorders, and obesity, as reviewed elsewhere (Post, 2004a, 2004b, 2005). Thus, a considerable amount of polypharmacy and polypsychotherapy may be required to match the panoply of bipolar presentations and comorbidities.

In contrast, in a patient who is in the early stages of bipolar illness after only several episodes or is currently in a substantially improved state, we have found the utility of discriminating the notion of achieving “perfection” in the psychopharmacological as opposed to the psychotherapeutic realm. For many with unipolar and bipolar illness, the striving for psychological perfection is problematic and is a target for psychotherapeutic amelioration in the service of a more successful outcome. In contrast, emphasizing that the psychopharmacological goal is for “perfection” in terms of achieving and maintaining a full remission would appear to have some merit as it pertains to hopefulness, compliance, and the required monitoring intensity, such that minor symptoms can be dealt with before they become problematic. Stating that this type of perfection can be an agreed upon goal of long-term maintenance therapy often evokes a very favorable response on the patient’s part, because this has often been their secret goal all along, that is, achieving and maintaining an essential remission, and they are pleased that this is also supported by the treating clinician and physician.

Examples of practical adjunctive psychosocial interventions for those at high risk

When considering a shift in public health approaches to early intervention in children at high risk for an affective disorder, it would appear appropriate to start such a consideration with the areas that would likely have both the greatest impact and engender the least controversy.

Supports for those with postpartum depression

The postpartum period is a difficult time for almost any family, and if it is complicated by the presence of maternal depression, can be overwhelming. Thus, in obstetrics-gynecology practice, screening for depression both pre-and postpartum should be routine and no more overlooked than assessment of temperature, pulse, and blood pressure. Yet, it is rarely accomplished in a systematic fashion despite the common incidence of this condition, that is, almost 20% of all pregnancies (Gavin et al, 2005). Similarly, as the medical attention following the delivery is shifted from the mother to the intermediate and long-term care of the neonate, pediatricians should make the evaluation of maternal depression part of their routine child health care repertoire. Although these measures have often been suggested, a major gap remains in practice (Seehusen, Baldwin, Runkle, & Clark, 2005).

The importance of these screening measures needs to be taught as part of a routine practice in medical school, recommended in textbooks, and mandated as part of good practice by appropriate medical societies. Yet, each group is likely to say that such “extra” work and assessment is the purview of the other or another physician group, such as those involved in general care and family medicine, or specifically a psychiatrist. Left to this general sentiment, the needed changes are highly unlikely to occur until many years in the future. Another possible way to circumvent the inherent multiple public health, attitudinal, and systems difficulties, is to popularize the notion that pregnant individuals and newborns’ mothers should complete a readily available self-assessment scale and present the data to the appropriate specialist or generalist for subsequent evaluation and the appropriate action of treatment or referral if needed.

A number of recent studies have indicated that the notion of relative immunity from depression during pregnancy in someone with recurrent depression or bipolar disorder is, in fact, a myth (Cohen et al., 2004, 2006). Moreover, these individuals have a subsequently higher risk for a postpartum depression than the general population, and this needs to be considered as well.

Some practical suggestions for possible altered approaches to intervention and assistance once a diagnosis of postpartum depression has been reached are offered here in the spirit of starting a dialogue on what might be the most; appropriate interventions for individuals in other circumstances as well, and not with the idea that these are necessarily the best, most practical, or cost effective. The fact that they are often quite different from current practice and might engender considerable controversy would appear to help make the point that these and related measures for stress reduction and illness management deserve at least active discussion.

Because most US hospital stays for pregnancy and delivery have been drastically reduced from the previous routine of several days to the current 1 day or only overnight, it would appear reasonable that some of the loss of careful acute follow-up could be recouped by the provision on a regular basis of a home healthcare visit by a nurse practitioner on perhaps a once per week basis for the first month postpartum. This hypothetical individual’s agenda would be not only the assessment of vital signs and general maternal healthcare issues, but also a modicum of instruction about well baby care and facilitating the completion of observer and/or self-rated depression inventory for the new mother. For those found to have a postpartum depression, this individual could be recommended to continue weekly visits for the next several months. Moreover, this individual could assist in the referral and treatment acquisition process for more formal psychotherapeutic and psychopharmacological intervention as needed.

Conceptual approaches to building new support systems

Ideally, the depressed mother should also have someone available who could provide brief periods of child care assistance when she is overwhelmed and without other live-in resources. It would appear that the assignment of a person to provide the mother with a brief respite (i.e., a “time out” and a backup telephone number) would be a good starting place. If the baby is inconsolable and the mother exhausted, depressed, and demoralized, such a resource might be invaluable. This person could be conceptualized very much like the sponsors assigned in Alcoholics Anonymous who can be called if one is at high risk for ending their sobriety. This time-out individual would need to be viewed in a nonpejorative way as part of the routine treatment of postpartum depression and available to all mothers suffering from this potentially disabling disorder. As in Alcoholics Anonymous, the timeout person could be an unpaid volunteer, thus mitigating what would otherwise be an extraordinarily expensive medical supplement.

The older, multigenerational, extended-family structure used to provide such individuals on an almost round the clock basis in the person of a grandparent or other live-in family member. As the median number of adults per household in the United States is now two (and one is often away working) and there are very high numbers of single parent families, some modicum of this type of substitute grandparental or family relative support might need to come from the outside if it were to come at all.

Current mental health associations, advocacy groups, and foundations focused particularly on this issue of providing supplemental care for the mother with postpartum depression, and later, other aspects of bipolar illness itself, might be well suited to the task of developing such an endeavor. With the many millions and ever growing numbers of now well-bodied, highly experienced parents, grandparents, and great grandparents in retirement, such a group of older individuals could provide a very large pool for recruitment of volunteers. A several-tiered system might be necessary to respond to different levels of need. Some volunteers could staff telephones for advice, assistance, and support, while others with access to vehicles could be available for several hours for timeout duty at an individual patient’s residence when requested.

Need for immediate action

Critics would appropriately ask what evidence exists to support the effectiveness of such strategies as a visiting nurse and a time-out volunteer. A traditional way of proceeding is to gather preliminary and pilot study data first in order to justify such an effort. However, an alternative strategy may be more timely, efficient, and cost effective, that is, these and related types of programs that have both face validity and support from analogous efforts found effective in other areas of psychiatry and substance abuse prevention and intervention. Not only do Alcoholics Anonymous and related programs have proven positive track records, but they also often have controlled clinical trial data to document effectiveness. Moreover, a wealth of studies now document the short- and long-term efficacy of even minimalistic interventions, such as having a weekly visit by a nurse in homes with children at high risk (although not necessarily because of a mother’s postpartum depression). These studies show that these visits are associated with long-lasting positive effects that can be documented on measures such as increased high school graduation rates, and decreases in substance abuse and arrests compared with the control conditions (Eckenrode et al., 2001; Olds et al., 1999).

An important “negative” reason for not proceeding with the traditional mode of first demonstrating efficacy and then inaugurating these programs into more formal policies is the robust literature cited about the efficacy of psychotherapeutic and psychoeducational therapeutic modalities in bipolar illness compared with treatment as usual. Despite this small, but overwhelmingly positive literature, few of the studies definitively recommend that these measures now be incorporated into routine health care policy. Moreover, both supporters and critics of these studies point out that additional controlled studies are necessary to more adequately elucidate the nature of the “critical ingredients” mediating the success. Thus, the process of specification could prove relatively unending (perhaps requiring decades) before supporters and critics alike are satisfied with the fact that a given program has specified the precise mechanisms mediating efficacy.

Instead, it would appear vastly more efficient from both a time and cost perspective to inaugurate such face-valid programs from the outset and then perform appropriate efficacy and effectiveness studies during implementation. One could compare the relative effectiveness of two different interventions. This would not only allow study in situ, but revision of aspects of programs that appear most problematic and enhancement of others that appear particularly effective.

Training patients and advisory group members as educators

Although several novel public health measures in postpartum depression are discussed here in some detail, they are meant to be illustrative of similar policies, procedures, and studies directed al the many areas of vulnerability (discussed above) in those either at high risk or already with a diagnosis of bipolar illness. The development of programs in postpartum depression could also be used in applying similar types of strategies at each of the target points already shown to be associated with eventual prognosis in bipolar illness.

The former National Depressive and Manic Depressive Association (now the Depression and Bipolar Support Alliance) is proceeding with projects that involve formal training of patients to be peer supports and illness educators. The effectiveness of this type of paradigm has been demonstrated in Georgia and other states and venues. It could be immediately inaugurated, enhanced, and studied more widely, as sequenced in that order, respectively. Volunteer organizations can do what public health policy experts cannot readily do, that is, proceed immediately with much needed support services prior to the more academic, conventional, and ideal way of first demonstrating effectiveness and then changing procedures based on hard facts.

The imperatives for early action

In this paper we would redefine what are the critical facts that should be taken into consideration, however. The hard facts, documented above, are that bipolar illness in general is vastly underrecognized, underdiagnosed, and undertreated. Those with early-onset bipolar illness are at very high risk for a difficult, complicated, and partially treatment-resistant illness. First treatment can be delayed for decades and current treatment paradigms are poorly delineated. This ongoing inadequate approach to the illness has very grave and potentially life-long and life-threatening consequences for many individuals; it is a current and continuing disaster of huge personal, financial, and societal proportions (Post & Kowatch 2006). Waiting for other hard facts from the results of multiple controlled clinical trials would likely delay needed supplemental health care services to millions of individuals (in the United States alone) for many years if not decades.

Our current US health care system, which too often follows the principle of cutting immediate costs and services (many times at the expense of long-term savings and positive outcomes) in both the private and public arenas, is ill equipped, and one might say almost perfectly mismatched to the real needs of patients with bipolar illness. These individuals require intensive early support and careful, consistent, long-term monitoring, and multimodal pharmacological treatment and psychoeducational approaches. Even in countries where health care is covered by the government for all individuals, there is a shortfall in the delivery of these long-term approaches on a routine basis.

The stress of having a young child with bipolar illness (whether or not the parents are currently ill or depressed) can be enormous and often dismissed with the euphemistic term of “caregiver burden.” Providing a periodic in-home support and time-out individual to the euthymic, or especially depressed or manic, mother, or distraught father with a child who is irritable, labile, hyperactive, impulsive, explosive, aggressive, who does not sleep as much as usual, and switches rapidly from euphoria to profound depression (whether this is eventually classified as bipolar I, II, not otherwise specified, or merely bipolar-like), may have long-term, positive, illness-modifying effects for both the parents and the child.

Like the support programs suggested for postpartum depression, such an adjunctive support system could be routinely provided to a parent by volunteers in this potentially difficult if not desperate situation. This would not be intended as an alternative, but a supplement to the family and psychoeducational therapy provided by physicians and psychotherapy-oriented clinicians, be they PhDs, social workers, or nurses. The additional availability of such a time-out person could provide needed stress reduction to the parent and, as a side effect, potentially reduce instances of verbal or physical abuse elicited by and directed toward the “impossible child.”

Given the often great shortcomings in the treatment of bipolar illness in every age group and at every stage and transition point in its evolution, a new series of initiatives, a few of which are outlined here and many others, are needed to begin to help fill the gaps and supplement what is too often currently accepted as treatment as usual.