Gender Issues in the Treatment of Mental Illness

Schizophrenia in women

Epidemiology

Significant gender differences exist in the course and manifestation of schizophrenia. Although the incidence of schizophrenia has been widely reported to be approximately equal in men and women, a recent meta-analysis of the literature from the past two decades reported that the incidence risk ratio for men relative to women is between 1.31 and 1.42 (Aleman et al. 2003). The authors of this study suggested that these findings may reflect an increasing preponderance of schizophrenia in men in recent years. This increase may be related to the use of illicit drugs, which may precipitate the illness in genetically vulnerable men. Because oral contraceptives contain estrogen, which has dopamine-blocking effects in animal studies, the use of these agents may have had a protective effect in some women.

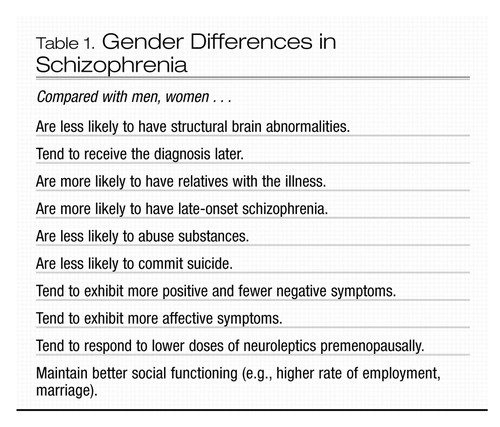

In men, rates of new-onset schizophrenia reach a peak between ages 15 and 24 years. For women, the peak occurs between ages 20 and 29 years. About 15% of women with schizophrenia do not develop the illness until their mid- or late 40s, possibly reflecting a response to the perimenopausal decline of estrogen (Aleman et al. 2003) (Table 1). For men, onset of the illness after age 40 years is rare. The diagnosis of schizophrenia is more likely to be delayed in women, in some cases possibly because of misdiagnosis of either major depression or bipolar disorder, as schizophrenia in women tends to be more affect-laden (Seeman 2004).

Other gender differences include a more favorable premorbid history in women and more favorable outcome, at least in the first 15 years after onset of the illness (Grigoriadis and Seeman 2002; Seeman 2004). Women with schizophrenia tend to experience more affective and positive symptoms and fewer negative symptoms (e.g., social withdrawal and lack of drive) than men. In addition, women who present initially with schizophrenia after age 45 years typically suffer fewer negative symptoms than either men of the same age with schizophrenia or age-matched women with early-onset schizophrenia (Lindamer et al. 1999). Structural brain abnormalities, such as increased ventricle size and decreased hippocampal volume, appear to be less common in women with schizophrenia than in men with the disorder (Cowell et al. 1996). Because relatives of women with schizophrenia are more likely to develop the illness, compared with relatives of men with schizophrenia, some researchers have suggested that schizophrenia is a more heritable illness in women and that environmental factors, such as birth complications, may be of more etiological significance in men (Castle and Murray 1991).

Special considerations in treatment

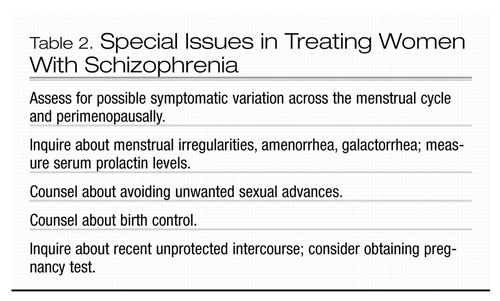

Issues in the treatment of women with schizophrenia are listed in Table 2. Some, but not all studies suggest that, compared with men, women respond better to treatment and may require lower doses of medication before menopause (Seeman 2004). Findings of a more favorable treatment response and course of illness in women have supported the speculation that estrogen may have a protective effect against schizophrenia (Szymanski et al. 1995). It is noteworthy that symptomatic exacerbation of schizophrenia and an increase in psychiatric hospital admission rates have been observed during the low-estrogen phases of the menstrual cycle (Bergemann et al. 2002; Choi et al. 2001; Seeman 1996; Szymanski et al. 1995) and in perimenopausal and postmenopausal years (Seeman 1986).

The menstrual patterns of women with schizophrenia should be monitored routinely. Careful clinical monitoring of symptoms in relation to the menstrual cycle, perhaps with the use of a diary, may be useful. If such monitoring indicates pre-menstrual worsening of symptoms, exacerbation of symptoms may be minimized by raising antipsychotic doses during the symptomatic pre-menstrual days. Women with schizophrenia should also be monitored carefully for worsening illness as they transition into menopause, as it may be necessary to increase antipsychotic doses at this time.

In a small double-blind, placebo-controlled study of acutely symptomatic premenopausal antipsychotic-treated women with schizophrenia, the use of transdermal estradiol as an adjunctive treatment resulted in significant improvement in psychotic symptoms (Kulkarni et al. 2001). Further studies are needed to determine whether estrogen may have a role as an adjunctive agent for the treatment of women with schizophrenia. Estrogen therapy in postmenopausal women has been associated with increased risks for cardiac events, pulmonary embolism, stroke, dementia, and breast cancer (Rossouw et al. 2002), and therefore estrogen therapy should not be used for the treatment of psychiatric symptoms unless its benefits clearly outweigh its risks.

Certain antipsychotic medications (e.g., risperidone, haloperidol, fluphenazine) can cause irregularities in the menstrual cycle by increasing levels of the pituitary hormone prolactin, which in turn inhibits release of follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) from the pituitary. As FSH is necessary for maturation of the ovarian follicles, a hyperprolactinemic state can prevent ovulation. Furthermore, hyperprolactinemia and the ensuing hypoestrogenemia can lead to a reduction in bone mineral density (Seeman 2004). Amenorrhea (i.e., absence of the menstrual cycle) is not unusual when prolactin levels exceed 60 ng/mL (normal prolactin levels are 5–25 ng/mL) (Seeman 1983). Galactorrhea, or nipple discharge, may also occur with elevated prolactin levels. If prolactin levels exceed 100 ng/mL, a brain-imaging study (preferably magnetic resonance imaging [MRI]), should be performed to rule out a prolactin-secreting pituitary tumor. Additional causes of elevated prolactin include pregnancy, nursing, stress, weight loss, opiate use, and use of oral contraceptives (Marken et al. 1992). For women of childbearing age with menstrual cycle disturbances, β-human chorionic gonadotropin (β-HCG) levels should be measured to test for pregnancy. Other relatively common causes of irregularities in the menstrual cycle include hypothyroidism and primary hyperprolactinemia. If hyperprolactinemia is determined to be secondary to the use of an antipsychotic agent, the dose should be reduced or the medication should be replaced with one of the newer antipsychotic agents, such as olanzapine, ziprasidone, aripiprazole, or quetiapine, which do not tend to raise prolactin levels. As an alternative, dopamine agonists such as bromocriptine (2.5–7.5 mg bid) or cabergoline (0.5 mg/week) can be used to reduce prolactin levels. At these low doses, bromocriptine does not appear to exacerbate psychosis. The effect of cabergoline on psychotic symptoms has not been evaluated. Cabergoline requires only once or twice weekly dosing and produces few side effects, whereas bromocriptine must be taken daily and can cause significant nausea. To minimize the nausea, bromocriptine should be taken with food. A third strategy is initiation of an oral contraceptive. This approach returns the patient to regular menstrual cycling and, by restoring estrogen, protects against the long-term adverse effects of a hypoestrogenic state, such as osteoporosis. In addition, this approach has the advantage of providing contraception. Prolactin levels, however, may rise with use of oral contraceptives and thus should be monitored closely. If prolactin levels rise or amenorrhea persists, the woman should be referred for a gynecological and endocrinological evaluation.

Women with schizophrenia are at particular risk for pregnancy resulting from ineffective use of birth control and high rates of sexual assault. Even women with antipsychotic-induced amenorrhea may occasionally ovulate and thus can become pregnant. Teaching women with schizophrenia about methods for birth control and strategies for avoiding unwanted sexual advances is an important aspect of treatment. Women with schizophrenia who become pregnant are at increased risk for stillbirth, preterm delivery, and low-birth-weight babies, and their newborns are at increased risk for sudden infant death syndrome (Bennedsen et al. 2001; Nilsson et al. 2002; Jablonsky et al. 2005). Women with schizophrenia are also at increased risk for giving birth to an infant with cardiovascular congenital anomalies (Jablonsky et al. 2005). Although the reasons for these findings are not clear, research in obstetric clinics has found that pregnant women with schizophrenia typically attend fewer than 50% of prenatal care appointments (Kelly et al. 1999), and inadequate prenatal care significantly increases the relative risk of preterm birth and postnatal death (Vintzileos et al. 2002a, 2002b). Clinicians working with pregnant schizophrenia patients should strongly encourage them to obtain regular prenatal care in an effort to improve their birth outcomes.

Mood disorders in women

Depression

Epidemiology

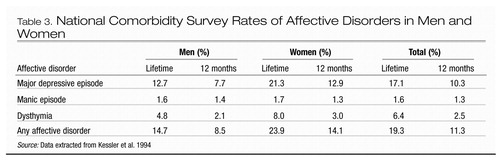

A number of large epidemiological studies have consistently found that women are more likely than men to experience depressive disorders (Choi et al. 2001; Weissman et al. 1984, 1991). The Epidemiologic Catchment Area study, the largest survey of psychiatric disorders in North America, reported a female-to-male ratio of 1.96:1 for major depression, with a lifetime prevalence of mood disorders of 10.2% in women and 5.2% in men (Weissman et al. 1991). Researchers in the National Comorbidity Survey used a structured psychiatric interview to evaluate a representative sample of the general population and reported higher rates of depression in both sexes (Table 3), with a lifetime rate of major depression of 21.3% in women and 12.7% in men, producing a female-to-male ratio of 1.68:1 (Kessler et al. 1993, 1994). The increased prevalence of depression in women begins in adolescence and is a cross-cultural phenomenon (Bland et al. 1988; Wells et al. 1989; Wittchen et al. 1992). Although most exogenous stressors influence the risk for depression similarly in both women and men, women appear to be more likely to become depressed in response to interpersonal difficulties within their close family networks, and men appear more likely to become depressed in response to occupational difficulties (job loss, work problems) (Kendler et al. 2001). Although the female preponderance for depression has been shown across countries (Wittchen et al. 1992), it does not necessarily occur in select populations within these countries. Thus, although Jewish individuals have higher rates of depression than do other population groups, the female-to-male ratio for depression is 1:1; the lack of gender difference may be due to the lower rate of alcoholism among Jewish men and the inverse relationship between alcoholism and major depression (Levav et al. 1997). However, for dysthymia, the prevalence is twice as high in women, with lifetime rates of 5.4% for women and 2.6% for men (Kessler et al. 1993). The preponderance of depression in women is even higher for atypical depression (i.e., depression characterized by mood reactivity and at least one of the following symptoms: hypersomnia, hyperphagia, leaden paralysis, rejection sensitivity) and for seasonal affective disorder (SAD) (Rosenthal et al. 1984). Although female gender increases the risk for major depression and dysthymia, data from the National Comorbidity Survey suggest that a prior history of an anxiety disorder increases the risk for these conditions still more (Parker and Hadzi-Pavlovic 2001) These findings suggest that the female preponderance for depression and dysthymia might be determined primarily by a gender difference in the prevalence of anxiety disorders (Parker and Hadzi-Pavlovic 2001).

Special considerations in treatment

Whether there are gender-based differences in response rates for different antidepressants is a subject of controversy. Thus, although some authors have suggested that, compared with men, women respond better to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors than to the tricyclic antidepressant imipramine (Kornstein et al. 2000), data from more than 1,700 depressed men and women indicate that for adult patients up to age 65 years, response rates are equivalent for both tricyclic antidepressants and fluoxetine (Quitkin et al. 2002). Women seemed to have a statistically superior response to monoamine oxidase inhibitor antidepressants, but that difference did not appear to be clinically significant (Quitkin et al. 2002). A recent study found that response to tricyclic antidepressants did not vary by gender (Wohlfarth et al. 2004).

In providing pharmacological treatment to women of reproductive age, it is important to keep in mind the possibility of pregnancy. Therefore, sexually active women should be advised to use an effective method of contraception. For women who are planning to conceive and who may require continued use of medication during pregnancy, choosing an antidepressant that appears safe during pregnancy may prevent the need to switch medications after conception. Some women with depression experience premenstrual exacerbation of their symptoms (Wohlfarth et al. 2004) and thus may experience a worsening of premenstrual symptoms despite successful treatment of depression at other times of the month (see Chapter 2, section titled “Evaluation”). For women who exhibit monthly exacerbation of a depression that is otherwise responsive to pharmacotherapy, it may be useful to chart the timing of the symptoms. If there appears to be a consistent premenstrual exacerbation of depression, an increase in antidepressant dose 7–10 days before the onset of menses may help maintain euthymia throughout the cycle (Jensvold et al. 1992; Yonkers 1997).

Certain antidepressants (including tricyclic anti-depressants and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors) may cause hyperprolactinemia as a result of their serotonergic activity (Marken et al. 1992). Although this effect is relatively rare, it is important to keep it in mind, particularly for patients taking antidepressants who complain of amenorrhea, galactorrhea (nipple discharge), or breast pain.

Women are far more likely than men to experience an eating disorder, and many women with eating disorders have comorbid depression. Because patients with anorexia or bulimia may have electrolyte imbalances that put them at particular risk for seizures, medications that reduce the seizure threshold (bupropion, clomipramine, maprotiline) should be avoided.

Women are at increased risk for depression during approximately the first 4–8 weeks after delivery (see Chapter 5, section titled “Postpartum Depression”), and this increase in risk is particularly true for women with a history of depression. For some women, prophylaxis with an antidepressant, begun 1–2 days after delivery, may decrease the likelihood of an episode of postpartum-onset major depression (Wisner and Wheeler 1994). Some data show that women with a history of depression related to the use of oral contraceptives or to the premenstruum or postpartum period are at risk of perimenopausal depression (Freeman et al. 2004; Stewart and Boydell 1993). Particularly in women with histories of depression, longitudinal monitoring for recurrence of depression at vulnerable points in the reproductive life cycle may allow for the rapid implementation of treatment and the prevention of a relapse.

Bipolar disorder

Epidemiology

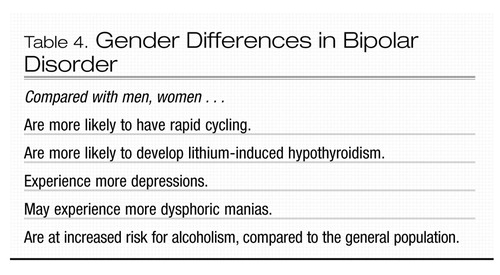

Although bipolar disorder occurs equally frequently in men and women, there are significant gender differences in its course and manifestation (Table 4). It has generally been accepted that women with the disorder appear to experience more depressive episodes than do men with the disorder, whereas men experience more manic episodes (Leibenluft 1996). However, two studies, one retrospective and one prospective, suggested that there may not be significant gender differences in the total number of depressive or manic episodes (Hendrick et al. 2000; Winokur et al. 1994). Dysphoric (mixed) mania may be more common in women (Leibenluft 1996). Women with bipolar disorder are approximately two times as likely as men with the disorder to experience rapid cycling, defined as four or more affective episodes per year (Tondo and Baldessarini 1998). The number of cycles occurring in men and women with rapid cycling does not appear to be significantly different, and both men and women appear to respond similarly to lithium treatment (Tondo and Baldessarini 1998). Why rapid-cycling bipolar disorder should occur more often in women is unclear. It may result from women’s greater likelihood of being treated with antidepressants, which may precipitate rapid cycling (Wehr and Goodwin 1979). In addition, thyroid dysfunction is more common in women, and hypothyroidism has been implicated in rapid cycling. The data on the relationship between thyroid function and rapid cycling are mixed, as are the data on the use of thyroid supplementation for treatment of rapid cycling. Although more men than women with bipolar disorder experience comorbid alcohol and substance use disorders, when women and men with bipolar disorder were compared to women and men in the general population, the relative risk of comorbid alcohol and substance use disorders was greater for women with bipolar disorder (Frye et al. 2003).

Women with bipolar disorder may experience premenstrual relapse or exacerbation of symptoms (Hendrick et al. 1996). Mood fluctuations in women with rapid-cycling bipolar disorder, however, do not appear to vary consistently with the menstrual cycle (Leibenluft 1996; Leibenluft et al. 1999). Daily charting of moods allows an assessment of the relationship between menstrual cycle phases and mood changes. For women whose mood consistently deteriorates premenstrually, it is helpful to measure blood levels of medication both pre-menstrually and in the week postmenses, as serum levels of mood stabilizers may fluctuate across the menstrual cycle (Tondo and Baldessarini 1998).

Special considerations in treatment

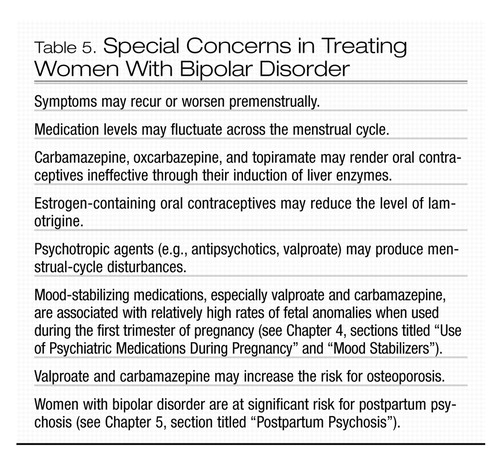

Gender-specific differences in presentation, clinical course, physiology, concomitant medications, and reproductive phase of life are all factors that should be considered when choosing among treatment options for bipolar disorder in women (Burt and Rasgon 2004). Special issues in the treatment of women with bipolar disorder are listed in Table 5. Because women who take lithium are at significant risk of developing lithium-induced hypothyroidism, thyroid function should be monitored at least every 6 months. Women older than age 40 years are particularly at risk for thyroid dysfunction, whether it is lithium-induced or results from another etiology.

By inducing hormone clearance and metabolism, carbamazepine, oxcarbazepine, and topiramate may reduce the efficacy of oral contraceptives. Women with bipolar disorder who are taking these antiepileptic drugs and oral contraceptives should therefore be advised to use a different or an additional form of contraception. Postmenopausal women taking carbamazepine, oxcarbazepine, or topiramate may find that they need higher doses of hormone replacement to reduce hypoestrogenemia-induced vasomotor symptoms (hot flashes, night sweats). Because oral contraceptives can reduce lamotrigine plasma levels by up to 60%, it is prudent for women who are taking both agents to have their lamotrigine doses monitored and adjusted as needed to maintain clinical efficacy (Sabers et al. 2001).

Several studies have examined whether the use of valproate puts women at an increased risk of developing polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), a heterogeneous condition characterized by irregular or absent menstrual cycles, hirsutism, and insulin resistance (Isojarvi et al. 1993; McIntyre et al. 2003; Rasgon 2004; Rasgon et al. 2000). Although the pathophysiology of PCOS is not well understood, hyperinsulinemia—a potential side effect of some medications, including valproate—is believed to play a role. The available information on the association between valproate and PCOS has been inconsistent, although some studies have identified high rates of menstrual disturbances among women with bipolar disorder, regardless of which medication they take (Isojarvi et al. 1993; Rasgon et al. 2000). Until more data are available, clinicians should be watchful for symptoms of menstrual irregularities and/or PCOS in patients with bipolar disorder, especially if they are taking valproate (Luef et al. 2002). Certain antipsychotic agents (e.g., risperidone, haloperidol) may also potentially cause amenorrhea or menstrual disturbances by elevating serum prolactin levels.

Obtaining a menstrual history is essential for assessing patterns of bipolar-disorder symptom exacerbation in relation to the menstrual cycle and for monitoring psychotropic-induced disturbances of the menstrual cycle pattern.

Some studies have reported an increased risk for osteoporosis among women taking carbamazepine or valproate (Pack and Morrell 2004). Several mechanisms have been suggested for this finding, including an increase in the metabolism of vitamin D, resistance to parathyroid hormone, and impaired calcium absorption. Although not all studies have observed this risk, it is probably wise to counsel women who take carbamazepine or valproate about good bone health practices, including adequate intake of calcium and vitamin D, regular weight-bearing exercise, adequate sunlight exposure, and avoidance of nicotine. Postmenopausal women who take carbamazepine or valproate should be encouraged to obtain a bone mineral density scan after 5 years of treatment.

Seasonal affective disorder

Epidemiology

Women are six times as likely as men to have seasonal affective disorder (SAD), a condition in which depressive episodes recur in a seasonal pattern. In “winter SAD,” symptoms of depression are limited to the fall and winter months; in “summer SAD,” depression occurs in the spring and summer. For perimenopausal women with SAD, symptoms typically occur in the fall and winter and include subjective dysphoria, hypersomnia, severe fatigue, increased appetite, and carbohydrate craving (Levitan et al. 1998). Winter SAD is more common in the Northern Hemisphere, whereas in the Southern Hemisphere there is a reversed seasonal variation. For patients with recurrent mood disorders (unipolar major depression, bipolar I disorder, or bipolar II disorder) who experience seasonal exacerbations of depression, the seasonal pattern specifier is added to their diagnosis. Although SAD may occur in children, the disorder tends to arise around puberty, worsen through adolescence, and become severe around the third decade of life. The changes in mood and behavior that characterize SAD (especially the winter type) run in families and appear to be largely due to a biological predisposition (Madden et al. 1996). Possible etiologies implicated in SAD are circadian rhythm changes, altered melatonin secretion, or serotonin dysfunction (Levitan et al. 1998).

Special considerations in treatment

Treatment of SAD includes the use of artificial light therapy (2,500 lux of light for 1–2 hours or 10,000 lux of light for 30 minutes generally administered in the morning). Although some patients respond to light administration only during the symptomatic months, maintenance light therapy may be required for patients with a more severe form of the illness. In some cases, adjunctive pharmacotherapy (generally year-round) is helpful to maintain remission from symptomatic season to season (Schwartz et al. 1996).

Anxiety disorders in women

Epidemiology

Anxiety disorders are the most prevalent psychiatric disorders, affecting one of every 10 people in the United States (Robins et al. 1984; Wells et al. 1989). As a class, anxiety disorders are more prevalent in women than in men, and women with anxiety disorders are more likely than men to experience comorbid depression (Pajer 1995; Pigott 2003). Panic with agoraphobia and generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) are two to three times more common in women than in men (Bourdon et al. 1988; Robins et al. 1984; Schneier et al. 1992), and social phobia is three to four times as common in women than in men (Schwartz et al. 1996). The rates of generalized anxiety disorder are stable in both women and men between the ages of 25 and 34 years but increase more in women older than 34 years than in age-matched men. Thus, the prevalence of GAD increases from about 1.5% in young men ages 15–24 years to 3.6% in men older than 45 years. However, in women the prevalence increases from 2.5% at age 15–24 years to 10.3% in women older than 45 years (Halbreich 2003). The rate decreases in aging men but further increases in women as they age (Robins et al. 1984). Women with panic disorder are just as likely as men to recover but are twice as likely to have a subsequent recurrence of symptoms (Yonkers et al. 1998).

Women with alcoholism are more likely to have panic disorder with agoraphobia than are men with alcoholism (Task Force on Panic Anxiety and Its Treatments 1993). Whether agoraphobia is a precipitant for alcoholism in women is unclear. Although the prevalence rates for obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) are approximately equal for men and women, women appear to have a somewhat later onset than do men (average age of 25 years in women versus 20 years in men) (Flament and Rapoport 1984). Whereas the overall lifetime prevalence of exposure to traumatic events does not vary by gender (Breslau et al. 1997), lifetime rates of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) are twice as high in women as in men (estimated at 10.4% for women and 5% for men) (Kessler et al. 1995). The reasons for the preponderance of anxiety disorders in women are not clear. Although genetic factors play a role in the transmission of anxiety disorders (Kendler et al. 1992, 1993), they have not been found to account for the gender differences in prevalence rates. Other possible causes for the preponderance of anxiety disorders in women include the increased prevalence rate of depression in women; the increased demands related to work and family that are currently placed on women; reproduction-related alterations in hormones; the relatively lower level of encouragement of self-sufficiency and self-confidence in girls, compared with boys; and histories of physical and sexual abuse (Pigott 2003; Zerbe 1995). With regard to PTSD, women may be culturally primed to experience traumatic events differently than men, rather than having an increased biological vulnerability. Thus, although women are more likely than men both to be molested and to subsequently develop PTSD, women are also more likely to develop PTSD after a physical assault despite the fact that men are much more likely to be victims of assault. However, although women are 10 times more likely than men to be raped, PTSD is more likely to result after this experience in men than in women (65% vs. 46%) (Yehuda 2002).

Special considerations in treatment

Evaluation for anxiety should first rule out medical conditions that present with anxious symptoms. In evaluating women patients for anxiety, the clinician should give particular attention to certain medical disorders. Although it appears that women with panic disorder are more likely to experience respiration-related difficulties than men with panic disorder (Sheikh et al. 2002), complaints of chest discomfort, diaphoresis, and tachycardia warrant a thorough diagnostic evaluation for heart disease. Women with these symptoms are more likely than men to be misdiagnosed as having an anxiety disorder and less likely than men to receive a cardiac assessment (Wenger et al. 1993). Mitral valve prolapse has been associated with panic disorder and is more prevalent in women (Yonkers and Gurguis 1995). The patient’s symptoms in relation to the menstrual cycle should also be evaluated, as women of reproductive age may experience premenstrual onset or worsening of anxiety. Patients with hypo- or hyperthyroidism may develop panic attacks with the onset of their thyroid condition. A thyroid panel should therefore be obtained in women reporting anxiety, tachycardia, diaphoresis, temperature intolerance, or tremor. Thyroid disease is more prevalent in women than in men, particularly in women older than age 40 years. Other medical illnesses that affect women more than men and that may present with symptoms of anxiety include systemic lupus erythematosus, iron deficiency anemia, and irritable bowel syndrome.

Nicotine and caffeine use should be assessed in women who report symptoms of anxiety and insomnia. Although in recent years the rate of cigarette smoking has declined in the general population, it has risen among teenage girls.

A full assessment of a patient’s medications should be part of the workup for an anxiety disorder. A number of medications may induce symptoms of anxiety, including decongestants, steroids, herbal supplements, and appetite suppressants.

The workup should also include an assessment of past and recent traumatic events. Women are more likely than men to experience rape and sexual assault, whereas men experience higher rates of nonsexual assault. Among women, rates of PTSD after sexual and nonsexual assault are estimated at 95% and 75%, respectively, within 2 weeks of the crime. Three months after the trauma, these rates diminish to approximately 50% for sexual assault and 25% for nonsexual assault. Female victims of sexual and nonsexual assault have been successfully treated with two forms of cognitive-behavioral treatment: prolonged exposure treatment and stress inoculation training (Foa 1997). Prolonged exposure treatment involves the patient’s repeated reliving of the trauma, combined with verbal recounting in therapeutic sessions, relaxation techniques, education about common reactions to trauma, and exposure to situations that remind the patient of the trauma. Stress inoculation training helps patients develop coping skills to deal with anxiety. These skills include muscle relaxation, breathing control, role-playing, thought-stopping, and self-dialogue.

Perimenopausal women may experience heat sensations, sweating, shortness of breath, and anxiety. For these women, vasomotor symptoms may be mistaken for panic or anxiety attacks (see Chapter 8, section titled “Physical changes”). A history of menstrual cycle alterations, measurement of the FSH level, and measurement of the estradiol level on day 2 or day 3 of the menstrual cycle (for women who are still cycling) can identify perimenopausal status. Hormone therapy rather than anxiolytic or antidepressant medication may suffice to resolve these symptoms if they are of vasomotor origin. Since estrogen and progestin therapy in post-menopausal women has been associated with increased risks for cardiac events, pulmonary embolism, stroke, dementia, and breast cancer, hormone therapy should be prescribed at the lowest effective dose for no more than 4–5 years (Rossouw et al. 2002).

Although women and men appear to have an equal prevalence of OCD, women seem to have more obsessions related to food and weight than do men, and women are also more likely to have comorbid anorexia (Kasvikis et al. 1986). It is therefore important to carefully evaluate all women with OCD for symptoms of restrictive-eating disorders.

Alcohol and substance abuse in women

Alcoholism

Epidemiology

Women are significantly less likely than men to have a drinking problem. The prevalence rate of alcoholism in men has been estimated at more than twice that in women (Walker et al. 2003). Nevertheless, alcoholism in adult women is not uncommon; its prevalence is estimated to be 6% and to be rising (Greenfield et al. 2003; Walker et al. 2003). Rates of alcoholism in young women, whose drinking patterns are approaching those of men, appear to be even higher (Walker et al. 2003).

Gender-specific physiological differences cause women to become more intoxicated than men when they drink an equal amount of alcohol per unit of body weight. Some reports suggest that alcohol dehydrogenase, the enzyme that degrades alcohol, is significantly less active in women (Blume 1994). In addition, as women have more body fat and less body water than do men, they reach higher blood alcohol levels because alcohol is diluted in total body water. Thus, although heavy drinking is considered to consist of more than four drinks a day in men, as little as one and one-half drinks a day may constitute heavy drinking for women (Cyr and Moulton 1990). Alcohol-related medical complications (e.g., peptic ulcer, liver disease, anemia, and cerebral atrophy) develop more quickly in women, and women have higher relative mortality rates from alcoholism than do men (Greenfield et al. 2003).

Risk factors for alcoholism

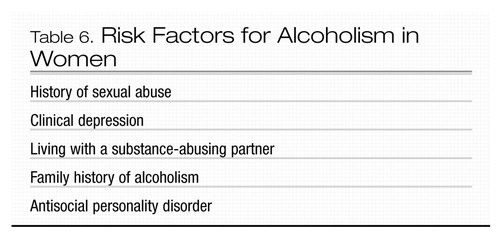

Risk factors in women include a personal history of sexual abuse, a family history of substance abuse, and adult antisocial personality disorder (Table 6). Depression is a much more significant risk factor for alcohol abuse in women than in men (Blume 1994). In fact, depression tends to precede alcoholism in women, whereas in men it tends to follow alcoholism (Blume 1994). Living with a substance-abusing partner is also a major risk factor for women and can reduce the likelihood that treatment will be successful.

Drug abuse

Epidemiology

As with alcohol abuse, the rates of abuse of hallucinogens and opiates are higher in men than in women. Cocaine and amphetamine abuse, however, are equally prevalent in men and women. Compared with men, women are less likely to inject cocaine and more likely to smoke and sniff cocaine (Gossop et al. 1994). Women may be motivated to use stimulants for weight control purposes. Rates of prescription drug abuse are higher in women, possibly because women go to doctors more often than do men. Also, women who abuse drugs or alcohol are more likely than men to have comorbid psychiatric diagnoses and thus to receive prescription medications (e.g., sedatives).

Risk factors for drug abuse

Risk factors for drug abuse include a family history of drug abuse, adult antisocial personality disorder, depression, and involvement with a drug-dependent partner (Griffin et al. 1989).

Screening and treatment

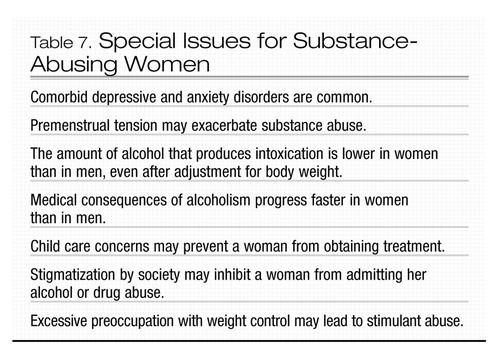

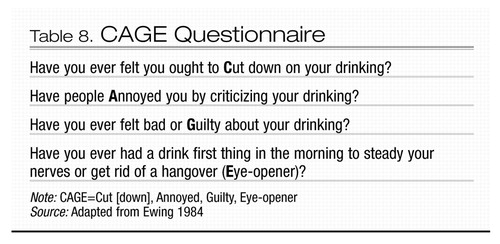

Special considerations in the screening and treatment of substance-abusing women are listed in Table 7. Any woman who presents with complaints of depression, anxiety, insomnia, sexual dysfunction, job problems, or family and marital conflicts should be assessed for substance abuse. Of particular concern is the direct request for specific prescription medications. Women who report great preoccupation with their weight should be assessed for the use of diet pills or stimulants. Although a careful history is the most important part of the evaluation, the CAGE questionnaire (Table 8) is a helpful screening instrument for alcoholism (Ewing 1984). Laboratory values are not reliably useful in screening for alcoholism, but they can help confirm the diagnosis. Elevated results on liver function tests, primarily the level of γ-glutamyltransferase (GGT), and a high mean corpuscular volume (MCV) suggest a history of extensive drinking. Medical problems such as peptic ulcer, hypertension, anemia, and liver disease result from heavy alcohol consumption and should prompt investigation into drinking patterns.

Noting the presence of alcohol- and drug-related legal and employment problems is helpful in making a diagnosis of substance abuse, although more so in men than in women. Women who abuse alcohol or drugs, on the other hand, are more likely to have family, interpersonal, and health problems (Cyr and Moulton 1993). Because depression frequently precedes or is comorbid with substance abuse in women, all women with alcoholism or drug dependence should be assessed for current and previous depressive episodes. If a woman has a history of depression preceding her substance dependence, she is at risk for a depressive relapse as she recovers (Blume 1994; Ewing 1984; Griffin et al. 1989). Treatment of depression may reduce the likelihood that the patient will return to substance abuse. For the same reason, comorbid anxiety disorders should be treated. Addictive prescription medications are best avoided, because women with alcoholism are at risk for prescription drug abuse. An assessment for premenstrual symptoms is important, because up to two-thirds of women with alcoholism may drink to self-medicate premenstrual tension (Hendrick et al. 1996). Treatment of the premenstrual symptoms may reduce the alcohol use.

For any treatment plan to be effective, it is essential that the substance-abusing woman accept that she has an illness and recognize the interpersonal, psychological, and medical consequences of her drug use. Referrals to self-help groups—including Alcoholics Anonymous, Cocaine Anonymous, and Women for Sobriety, an all-woman support group—are important aspects of treatment. The woman’s family should be involved; family support and concern may help motivate the patient to remain in recovery. Family members can benefit from referrals to Al-Anon. Because a woman’s drinking or drug use pattern is greatly influenced by that of her partner, her likelihood of reaching sobriety is enhanced if her partner is sober. Thus, an evaluation of the partner’s drinking or drug use patterns is important. If the partner also has a substance use problem, he or she should be encouraged to obtain treatment. Family and marital conflicts may contribute to a woman’s drinking or drug use and should be explored. Attention should be given to child care needs that may interfere with a woman’s ability to obtain treatment.

Societal stigmatization of women drinkers may cause women to hide drinking problems. Women may also fear losing custody of their children if they reveal their alcoholism. It is therefore essential that women with alcoholism be treated in a non-judgmental and supportive manner. Group and individual therapy are helpful, particularly in addressing issues of shame and low self-esteem and in promoting assertiveness.

Eating disorders in women

Epidemiology and phenomenology

The combined prevalence of anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa is approximately 4%, with more than 90% of cases occurring in women (Leach 1995). These illnesses typically develop in puberty and are more common in industrialized societies. Anorexia nervosa is characterized by a body weight of less than 85% of the expected weight for age and height, intense fear of gaining weight, distorted body image, and (in postmenarcheal females) amenorrhea. Anorexia nervosa is categorized as one of two types: restricting type or binge-eating/purging type. Approximately 50% of cases fall into each category (Mickley 2000). Patients with bulimia nervosa engage in episodes of binge-eating, in which they experience a sense of lack of control over eating and are excessively concerned about body image. They attempt to compensate for their food intake by self-induced vomiting; use of laxatives, diuretics, and enemas; excessive exercise; or fasting. The DSM-IV-TR diagnosis of bulimia nervosa requires that the binge-eating and compensatory behaviors occur at least twice a week for at least 3 months. The disorder is categorized as either purging type (i.e., involving the use of self-induced vomiting, laxatives, diuretics, or enemas) or nonpurging type. Patients with bulimia are usually normal in weight. Anorexia and bulimia nervosa are frequently accompanied by mood, anxiety, personality, and substance use disorders. A history of substance use disorders and a longer duration of symptoms predict worse treatment outcomes (Keel et al. 1999).

Screening and treatment

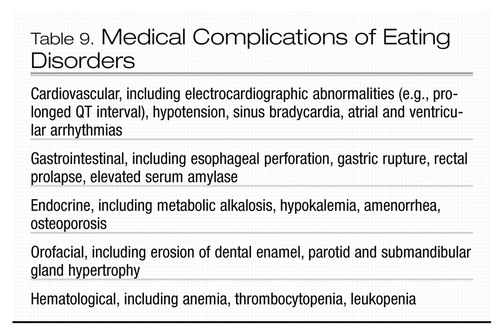

The evaluation of women with eating disorders should include assessments of body image; eating habits; actual and desired weight; menstrual patterns; exercise; self-induced vomiting; presence of other psychiatric disturbance; use of laxatives, diuretics, enemas, emetics, and diet pills; and abuse of alcohol and illicit substances. A number of medical complications may result from anorexia and bulimia nervosa (Table 9) (Becker et al. 1999). Therefore, the evaluation should include a physical and dental examination and laboratory tests for albumin, total protein, and glucose levels to help assess nutritional status. Measurement of amylase levels gives an indication of the extent of self-induced vomiting. Measurement of electrolytes, blood urea nitrogen, and creatinine levels are essential for assessing fluid and electrolyte abnormalities. A complete blood count can reveal anemia from nutritional deficiency and from internal bleeding—for example, from esophageal tears resulting from self-induced vomiting. An electrocardiogram should be obtained because cardiac conduction abnormalities may occur as a result of electrolyte imbalance, malnutrition, and ipecac-induced cardiomyopathy.

The treatment of eating disorders should involve a multidisciplinary team including mental health professionals and a primary care physician, nutritionist, and dentist. The first priority for treatment is medical stabilization to correct malnutrition, electrolyte imbalance, and other serious medical problems. In life-threatening conditions, nasogastric tube feeding may be necessary. After medical stabilization, the treatment involves the establishment of healthful eating patterns and attention to the psychosocial precipitants of the condition (Leach 1995). Psychosocial interventions include family counseling, individual/couples psychotherapy, education, and group support. Two forms of structured, time-limited therapy have been effective in the treatment of bulimia nervosa: cognitive-behavioral therapy, which focuses on the relationship between thoughts, feelings, and behavior; and interpersonal therapy, which addresses the interpersonal stressors that precipitate disordered eating (Becker et al. 1999). Certain antidepressant medications, including fluoxetine, have been helpful for bulimia nervosa (Leach 1995). High doses (e.g., 60 mg/day) have been more effective than lower doses. Monoamine oxidase inhibitors (e.g., phenelzine, isocarboxazid) have also been effective but should be used only for patients who are able to avoid tyramine-containing foods. Antidepressant medications have been of little help in treating the symptoms of anorexia nervosa, although they are clearly indicated for associated mood and anxiety disorders. Tricyclic antidepressants can be helpful in promoting weight gain. Topiramate has been reported to be useful in reducing both bingeing and purging (Hoopes et al. 2003).

Most patients with anorexia nervosa will require intensive treatment in an inpatient setting or day program, where they can be supported in eating and weight gain restoration. Patients should be hospitalized if their body weight is 25% below normal, if they experience medical complications, or if they are refusing food. Weight gain should proceed at 2–3 lbs/week for inpatients and 1–2 lbs/week for outpatients. Patients with bulimia nervosa can usually be managed in outpatient settings. For both disorders, long-term maintenance therapy is recommended.

Sleep disorders in women

In 1995, the prevalence rate of chronic insomnia was 12%, with women having a rate 1.3 times higher than that of men (Millman 1999). The risk for sleep-related difficulties rises during certain reproductive phases of women’s lives: premenstrual bloating and cramping frequently disrupt sleep, as does the discomfort women experience in the third trimester of pregnancy, and night sweats produce sleep impairment in approximately one-third of perimenopausal women (Walsleben 1999).

Other common causes of insomnia include depression and anxiety disorders, side effects of medications (e.g., bronchodilators, blood pressure medications, decongestants), and use of alcohol, caffeine, nicotine, and illicit drugs. A number of medical conditions (e.g., asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, sleep apnea) produce insomnia by causing shortness of breath at night. Disruptions in circadian rhythm commonly caused by jet lag or rotating work shifts can produce insomnia. A restless limb syndrome, characterized by discomfort in the legs and sometimes in the arms, can also disrupt sleep.

A detailed history should be obtained to determine the etiology of the insomnia. If the underlying cause is a psychiatric or medical problem, the problem should be treated. The elements of sleep hygiene should be reviewed, including reduction in use of caffeine, nicotine, and alcohol; avoidance of napping during the day; maintenance of regular exercise; avoidance of excessive fluids in the evening; and maintenance of regular times for sleeping and waking up (Millman 1999). If sleep problems are associated with premenstrual phases, low-dose oral contraceptives may help, and short-term hormone therapy at the lowest effective dose will reduce night sweats that disrupt sleep in middle-aged women (Polo-Kantola et al. 1999). When sleep-promoting modalities are ineffective, it may be appropriate to prescribe a hypnotic agent. Benzodiazepines are the most common class of medications for the treatment of insomnia. A meta-analysis of controlled studies of the use of benzodiazepines for the treatment of insomnia revealed that both benzodiazepines and the non-benzodiazepine hypnotic zolpidem produced improvement in patients with chronic insomnia (Nowell et al. 1997). However, hypnotics should be generally prescribed only for short-term use, because long-term use raises concerns of addiction and rebound insomnia after withdrawal of the medication. Sedating antidepressants (e.g., trazodone, doxepin) can be used in place of traditional agents such as benzodiazepines to treat insomnia. Few studies have evaluated the efficacy and safety of these agents to treat insomnia over the long term.

Women victims of violence

Sexual assault

Epidemiology

Sexual assault is defined as any form of nonconsenting sexual activity. Despite the fact that rape is a felony, most rapes are not reported (Petter and Whitehill 1998). It is estimated that only one of 10 victims of sexual assault seeks professional help (Beckman and Groetzinger 1990). Sexual assault affects women of all ages and all cultural, ethnic, and economic backgrounds. Approximately 20%–25% of all adult women, 15% of college women, and 12% of adolescent girls have experienced sexual abuse and/or assault during their lifetime, and rates are even higher for African American women (Council of Scientific Affairs, American Medical Association 1992; Silverman et al. 2001). Each year, more than 1.5 million women in the United States are physically and/or sexually abused by an intimate partner, and women are 10 times more likely than men to be killed by an intimate partner (Silverman et al. 2001). Although adolescents and young adult women are most at risk for sexual abuse by an acquaintance or someone unknown to them, older women are more likely to be sexually assaulted by marital or ex-marital partners (Council of Scientific Affairs, American Medical Association 1992).

Special considerations in treatment

Most emergency departments have established protocols for rape victims that involve extensive and detailed physical evaluation, laboratory tests, and collection of evidence for possible legal action. Although both recent and past assaults threaten the psychological and physical well-being of women, only a small minority of victims actually come forth to acknowledge the assault.

Initial reactions to sexual assault vary from woman to woman and include shock, numbness, withdrawal, and denial. Physical signs often include severe tremulousness and cold sweats. The victim of assault by a stranger is often fearful of further harm, whereas the victim of assault by an acquaintance or intimate tends to be dismayed that she has been assaulted by a trusted person. When a husband or live-in partner rapes a woman, the victim may initially be numb and accepting, although she ultimately may be driven by anger and fear to seek help. It is not unusual for women who have been sexually assaulted to experience stress reactions over a period of days to weeks, including intense startle reactions, disturbed sleep and appetite, fatigue, and headache.

Virtually no victim of sexual assault escapes some form of negative psychological sequela. Initial symptoms tend to dissipate over several weeks, but symptoms often return and intensify. Over the longer term, women who have been sexually assaulted feel out of control, ashamed, vulnerable, guilty, and depressed. They often experience sexual dysfunction and aversion and may have difficulty maintaining healthy interpersonal relationships (Stewart and Robinson 1995). Symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder are common and are particularly intense when there is a history of abuse (Stewart and Robinson 1995).

Ideally, the initial psychiatric interview should include an assessment of the patient’s current symptoms, her pre-assault level of functioning, the presence of supportive significant others, and the provision of crisis management if needed for short-term safety. In fact, because the patient who has been acutely sexually assaulted is often in shock, many of the components of the initial psychiatric evaluation may be deferred. Comorbid psychiatric illness should be treated in order to facilitate management of post-rape psychiatric difficulties. It is important to educate the patient and any significant others about what she is likely to experience over the ensuing weeks. Psychotherapy is useful for assisting rape victims as they deal with new and recurring symptoms. Even if treatment is declined, the rape victim should be given the option for therapy at a later time.

Psychotherapy may use cognitive-behavioral, supportive, or psychodynamic approaches or a mixture of psychotherapeutic modalities. Group therapy is also helpful in validating the patient’s experience in a safe setting where other victims can acknowledge common experiences and provide support and practical assistance. It is important for the therapist to empathically listen to the patient’s recounting of her experience as it relates to her altered sense of self and as it threatens her ability to function. The therapeutic setting should provide a temporary “holding environment” until the patient is able to resurrect her own sense of security and safety (Stewart and Robinson 1995). The patient should not be pressured into revealing any details with which she is uncomfortable. Medication may be helpful in treating depression, PTSD, or general symptoms of anxiety. Although patients should be reassured that over time their stress symptoms will dissipate, they should also be advised that should symptoms recur in response to other crises or important life events a brief return to psychotherapy may be helpful.

Domestic violence

Epidemiology

Women are more likely to be assaulted and injured by a current or former male partner than by all other assailants combined (Council of Scientific Affairs, American Medical Association 1992). According to a 1985 survey, physical violence aimed at a wife by her husband occurs in one of eight cohabiting couples (Council of Scientific Affairs, American Medical Association 1992). Because data on domestic violence do not fully represent the poor or the non-English-speaking population, the estimate of 2 million female victims of partner assault per year should probably be substantially increased by as much as a factor of two (Council of Scientific Affairs, American Medical Association 1992). It is noteworthy that women who have been assaulted in the past by a partner are at high risk for being assaulted again by the same partner. More than one-third of assaults involves acts of severe aggression, including choking, punching, kicking, beating, or using a weapon. Sexual assaults, psychological abuse, and threats also fall under the category of domestic violence. The rate of assaults to pregnant wives is estimated at 7% (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 1994), and pregnant women who are abused tend to be beaten on the abdomen, in contrast to nonpregnant women, who are usually struck in the face (Stewart and Robinson 1995). At the time of the assault, women often feel that their lives are in danger, and these fears may persist after the assault. Although women do assault male and female partners, the nature of injuries to victims of domestic violence tends to be much more serious when the perpetrator is a man.

Victims of domestic violence are at risk for serious physical injury and death. Additional sequelae of domestic violence include obstetric and perinatal complications, sexually transmitted diseases, gynecologic and medical problems, depression, anxiety, eating disorders, and alcoholism (Eisenstat and Bancroft 1999). Children of battered women may suffer injury themselves and are at risk for substance abuse, suicide, school problems, violent and aggressive behavior, sleep disorders, enuresis, and chronic somatic disorders (Eisenstat and Bancroft 1999).

Special considerations in treatment

Women are often reluctant to spontaneously disclose that they have been abused by their partners. Nevertheless, because of the high prevalence of domestic violence, women who present to the offices of physicians and other health professionals with ambiguous physical findings should be evaluated in private for physical abuse. Since battering often increases during pregnancy (Eisenstat and Bancroft 1999), screening should be routinely performed during obstetric visits. Two screening questions have been found to have a sensitivity of 71% and a specificity of almost 85% in detecting domestic violence: “Do you ever feel unsafe at home?” and “Has anyone at home hit you or tried to injure you in any way?” (Eisenstat and Bancroft 1999). It is important for every health care provider to become familiar with the legal reporting requirements for domestic violence. In some states, clinicians are required to report domestic violence to local authorities. Reporting is particularly challenging, given that victims often do not wish to bring attention to the abuse because they are afraid of reprisals. Perhaps the most important function of the health care provider is to inform the patient of viable options for getting help and removing herself from danger. A national phone number, 1-800-799-SAFE, can be called for information on hospital and local community resources. Every health care provider should have a list of local resources to provide directly to women who report being abused by their partners.

Women victims of domestic violence experience acute and chronic symptoms similar to those of rape victims. During the assault, there is fear for one’s life. After an assault, women tend to experience, shock, denial, isolation, confusion, psychological numbness, and fear. Over the long term, women victims of domestic violence experience sleep and appetite disturbance, startle reactions, physical complaints, fatigue, anxiety, and depression (Stewart and Robinson 1995). The fact that the abuse occurred in the context of a relationship with legal, financial, and (sometimes) shared parental relationships makes it very difficult for women to extricate themselves from the circle of abuse. Mental health clinicians should be supportive and empathic. Comorbid psychiatric conditions should be managed in order to facilitate appropriate care of the traumatic sequelae with which the patient presents. The initial therapeutic approach should be individual rather than conjoint or family, as couples’ therapy is likely to precipitate defensive behaviors. The perpetrator may, however, also be willing to obtain individual therapy. If the partners wish to continue their relationship, eventually conjoint therapy should be instituted. In some cases, the use of pharmacotherapy may be needed to facilitate treatment of depression or anxiety.

|

Table 1. Gender Differences in Schizophrenia

|

Table 2. Special Issues in Treating Women With Schizophrenia

|

Table 3. National Comorbidity Survey Rates of Affective Disorders in Men and Women

|

Table 4. Gender Differences in Bipolar Disorder

|

Table 5. Special Concerns in Treating Women With Bipolar Disorder

|

Table 6. Risk Factors for Alcoholism in Women

|

Table 7. Special Issues for Substance-Abusing Women

|

Table 8. CAGE Questionnaire

|

Table 9. Medical Complications of Eating Disorders

Aleman A, Kahn RS, Selten JP: Sex differences in the risk of schizophrenia: evidence from meta-analysis. Arch Gen Psychiatry 60:565–571, 2003Crossref, Google Scholar

Becker AE, Grinspoon SK, Klibanski A, et al: Eating disorders. N Engl J Med 340:1092–1098, 1999Crossref, Google Scholar

Beckman CR, Groetzinger LL: Treating sexual assault victims: a protocol for health professionals. Physician Assist 14:128–130, 1990Google Scholar

Bennedsen BE, Mortensen PB, Olesen A, et al: Congenital malformations, stillbirths, and infant deaths among children of women with schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 58:674–679, 2001Crossref, Google Scholar

Bergemann N, Parzer P, Nagl I, et al: Acute psychiatric admission and menstrual cycle phase in women with schizophrenia. Arch Womens Ment Health 5:119–126, 2002Crossref, Google Scholar

Bland RC, Orn H, Newman SC: Lifetime prevalence of psychiatric disorders in Edmonton. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl 338:24–32, 1988Crossref, Google Scholar

Blume SB: Gender differences in alcohol-related disorders. Harv Rev Psychiatry 2:7–14, 1994Crossref, Google Scholar

Bourdon KH, Boyd JH, Rae DS, et al: Gender differences in phobias: results of the ECA community survey. J Anxiety Disord 2:227–241, 1988Crossref, Google Scholar

Breslau N, Davis GC, Andreski P, et al: Sex differences in posttraumatic stress disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 54:1044–1048, 1997Crossref, Google Scholar

Burt VK, Rasgon N: Special considerations in treating bipolar disorder in women. Bipolar Disord 6:2–13, 2004Crossref, Google Scholar

Castle DJ, Murray RM: The neurodevelopmental basis of sex differences in schizophrenia. Psychol Med 21:565–575, 1991Crossref, Google Scholar

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Physical violence during the 12 months preceding childbirth—Alaska, Maine, Oklahoma, and West Virginia, 1990–1991. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 43:132–137, 1994Google Scholar

Choi SH, Kang SB, Joe SH: Changes in premenstrual symptoms in women with schizophrenia: a prospective study. Psychosom Med 6:822–829, 2001Crossref, Google Scholar

Council of Scientific Affairs, American Medical Association: Violence against women: relevance for medical practitioners. JAMA 267:3184–3189, 1992Crossref, Google Scholar

Cowell PE, Kostianovsky DJ, Gur RC, et al: Sex differences in neuroanatomical and clinical correlations in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 153:799–805, 1996Crossref, Google Scholar

Cyr MG, Moulton AW: Substance abuse in women. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am 17:905–925, 1990Google Scholar

Cyr MG, Moulton AW: The physician’s role in prevention, detection, and treatment of alcohol abuse in women. Psychiatr Ann 23:454–462, 1993Crossref, Google Scholar

Eisenstat SA, Bancroft L: Domestic violence. N Engl J Med 341:886–892, 1999Crossref, Google Scholar

Ewing JA: Detecting alcoholism: the CAGE questionnaire. JAMA 252:1905–1907, 1984Crossref, Google Scholar

Flament MF, Rapoport JL: Childhood obsessive-compulsive disorder, in New Findings in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. Edited by Insel TR. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1984, pp 23–43Google Scholar

Foa EB: Trauma and women: course, predictors, and treatment. J Clin Psychiatry 58(suppl 9):25–28, 1997Google Scholar

Freeman EW, Sammel MD, Liu L, et al: Hormones and menopausal status as predictors of depression in women in transition to menopause. Arch Gen Psychiatry 61:62–70, 2004Crossref, Google Scholar

Frye MA, Altshuler LL, McElroy SL, et al: Gender differences in prevalence, risk, and clinical correlates of alcoholism comorbidity in bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry 160:883–889, 2003Crossref, Google Scholar

Gossop M, Griffiths P, Powis B, et al: Cocaine: patterns of use, route of administration, and severity of dependence. Br J Psychiatry 164:660–664, 1994Crossref, Google Scholar

Greenfield SF, Manwani SG, Nargiso JE: Epidemiology of substance use disorders in women. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am 30:413–446, 2003Crossref, Google Scholar

Griffin ML, Weiss RD, Mirin SM, et al: A comparison of male and female cocaine abusers. Arch Gen Psychiatry 46:122–126, 1989Crossref, Google Scholar

Grigoriadis S, Seeman MV: The role of estrogen in schizophrenia: implications for schizophrenia practice guidelines for women. Can J Psychiatry 47:437–442, 2002Crossref, Google Scholar

Halbreich U: Anxiety disorders in women: a developmental and life-cycle perspective. Depress Anxiety 17:107–110, 2003Crossref, Google Scholar

Hendrick V, Altshuler LL, Burt VK: Course of psychiatric disorders across the menstrual cycle. Harv Rev Psychiatry 4:200–207, 1996Crossref, Google Scholar

Hendrick V, Altshuler LL, Gitlin MJ, et al: Gender and bipolar illness. J Clin Psychiatry 61:393–396, 2000Crossref, Google Scholar

Hoopes SP, Reimherr FW, Hedges DW, et al: Treatment of bulimia nervosa with topiramate in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, part 1: improvement in binge and purge measures. J Clin Psychiatry 64:1335–1341, 2003Crossref, Google Scholar

Isojarvi JI, Laatikainen TJ, Pakarinen AJ, et al: Polycystic ovaries and hyperandrogenism in women taking valproate for epilepsy. N Engl J Med 329:1383–1388, 1993Crossref, Google Scholar

Jablensky AV, Morgan V, Zubrick SR, et al: Pregnancy, delivery, and neonatal complications in a population cohort of women with schizophrenia and major affective disorders. Am J Psychiatry 162:79–91, 2005Crossref, Google Scholar

Jensvold MF, Reed K, Jarrett DB, et al: Menstrual cycle-related depressive symptoms treated with variable antidepressant dosage. J Womens Health 1:109–115, 1992Crossref, Google Scholar

Kasvikis JG, Tsakiris F, Marks IM: Past history of anorexia nervosa in women with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Int J Eat Disord 5:1069–1075, 1986Crossref, Google Scholar

Keel PK, Mitchell JE, Miller KB, et al: Long-term outcome of bulimia nervosa. Arch Gen Psychiatry 56:63–69, 1999Crossref, Google Scholar

Kelly RH, Danielsen BH, Golding JM, et al: Adequacy of prenatal care among women with psychiatric diagnoses giving birth in California in 1994 and 1995. Psychiatr Serv 50:1584–1590, 1999Crossref, Google Scholar

Kendler KS, Neale MC, Kessler RC, et al: Generalized anxiety disorder in women: a population-based twin study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 49:267–272, 1992Crossref, Google Scholar

Kendler KS, Neale MC, Kessler RC, et al: Panic disorder in women: a population-based twin study. Psychol Med 23:397–406, 1993Crossref, Google Scholar

Kendler KS, Thornton LM, Prescott CA: Gender differences in the rates of exposure to stressful life events and sensitivity to their depressogenic effects. Am J Psychiatry 158:587–593, 2001Crossref, Google Scholar

Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Swartz M, et al: Sex and depression in the National Comorbidity Survey. I: lifetime prevalence, chronicity and recurrence. J Affect Disord 29:85–96, 1993Crossref, Google Scholar

Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, et al: Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry 51:8–19, 1994Crossref, Google Scholar

Kessler RC, Sonnega A, Bromet E, et al: Posttraumatic stress disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry 52:1048–1060, 1995Crossref, Google Scholar

Kornstein SG, Schatzberg AF, Thase ME, et al: Gender differences in treatment response to sertraline versus imipramine in chronic depression. Am J Psychiatry 157:1445–1452, 2000Crossref, Google Scholar

Kulkarni J, Riedel A, de Castella AR, et al: Estrogen—a potential treatment for schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 48:137–144, 2001Crossref, Google Scholar

Leach AM: The psychopharmacotherapy of eating disorders. Psychiatr Ann 25:628–633, 1995Crossref, Google Scholar

Leibenluft E: Women with bipolar illness: clinical and research issues. Am J Psychiatry 153:163–173, 1996Crossref, Google Scholar

Leibenluft E, Ashman SB, Feldman-Naim S, et al: Lack of relationship between menstrual cycle phase and mood in a sample of women with rapid cycling bipolar disorder. Biol Psychiatry 15:577–580, 1999Crossref, Google Scholar

Levav I, Kohn R, Golding JM, et al: Vulnerability of Jews to affective disorders. Am J Psychiatry 154:941–947, 1997Crossref, Google Scholar

Levitan RD, Kaplan AS, Brown GM, et al: Hormonal and subjective responses to intravenous m-chlorophenylpiperazine in women with seasonal affective disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 55:244–249, 1998Crossref, Google Scholar

Lindamer LA, Lohr JB, Harris MJ, et al: Gender-related clinical differences in older patients with schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry 60:61–67, 1999Crossref, Google Scholar

Luef G, Abraham I, Haslinger M, et al: Polycystic ovaries, obesity and insulin resistance in women with epilepsy: a comparative study of carbamazepine and valproic acid in 105 women. J Neurol 249:835–841, 2002Crossref, Google Scholar

Madden PA, Heath AC, Rosenthal NE, et al: Seasonal changes in mood and behavior: the role of genetic factors. Arch Gen Psychiatry 53:47–55, 1996Crossref, Google Scholar

Marken PA, Haykal RF, Fisher JN: Management of psychotropic-induced hyper-prolactinemia. Clin Pharm 11:851–856, 1992Google Scholar

McIntyre RS, Mancini DA, McCann S, et al: Valproate, bipolar disorder and polycystic ovarian syndrome. Bipolar Disord 5:28–35, 2003Crossref, Google Scholar

Mickley D: Are you overlooking eating disorders among your patients? Women’s Health in Primary Care 3:40–52, 2000Google Scholar

Millman RP: Coping with insomnia: effective drug and non-drug therapies. Women’s Health in Primary Care 1:737–745, 1999Google Scholar

Nilsson E, Lichtenstein P, Cnattinguis S, et al: Women with schizophrenia: pregnancy outcome and infant death among their offspring. Schizophr Res 58:221–229, 2002Crossref, Google Scholar

Nowell PD, Mazumdar S, Buysse DJ, et al: Benzodiazepines and zolpidem for chronic insomnia: a meta-analysis of treatment efficacy. JAMA 278:2170–2177, 1997Crossref, Google Scholar

Pack AM, Morrell MJ: Epilepsy and bone health in adults. Epilepsy Behav 5 (suppl 2):S24–S29, 2004Crossref, Google Scholar

Pajer K: New strategies in the treatment of depression in women. J Clin Psychiatry 56 (suppl 2):30–37, 1995Google Scholar

Parker G, Hadzi-Pavlovic D: Is any female preponderance in depression secondary to a primary female preponderance in anxiety disorders? Acta Psychiatr Scand 103:252–256, 2001Crossref, Google Scholar

Petter LM, Whitehill DL: Management of female sexual assault. Am Fam Physician 58:920–926, 929–930, 1998Google Scholar

Pigott TA: Anxiety disorders in women. Psychiatr Clin North Am 26:621–672, vi–vii, 2003Google Scholar

Polo-Kantola P, Erkkola R, Irjala K, et al: Effect of short-term transdermal estrogen replacement therapy on sleep: a randomized, double-blind crossover trial in postmenopausal women. Fertil Steril 71:873–880, 1999Crossref, Google Scholar

Quitkin FM, Stewart JW, McGrath PJ, et al: Are there differences between women’s and men’s antidepressant responses? Am J Psychiatry 159:1848–1854, 2002Crossref, Google Scholar

Rasgon N: The relationship between polycystic ovary syndrome and antiepileptic drugs: a review of the evidence. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 24:322–334, 2004Crossref, Google Scholar

Rasgon NL, Altshuler LL, Gudeman D, et al: Medication status and polycystic ovary syndrome in women with bipolar disorder: a preliminary report. J Clin Psychiatry 61:173–178, 2000Crossref, Google Scholar

Robins LN, Helzer JE, Weissman MM, et al: Lifetime prevalence of specific disorders in three sites. Arch Gen Psychiatry 41:949–958, 1984Crossref, Google Scholar

Rosenthal NE, Sack DA, Gillin JC, et al: Seasonal affective disorder: a description of the syndrome and preliminary findings with light therapy. Arch Gen Psychiatry 41:72–80, 1984Crossref, Google Scholar

Rossouw JE, Anderson GL, Prentice RL, et al: Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women. JAMA 288:321–333, 2002Crossref, Google Scholar

Sabers A, Buchholt JM, Uldall P, et al: Lamotrigine plasma levels reduced by oral contraceptives. Epilepsy Res 47:151–154, 2001Crossref, Google Scholar

Schneier FR, Johnson J, Hornig CD, et al: Social phobia: comorbidity and morbidity in an epidemiologic sample. Arch Gen Psychiatry 49:282–288, 1992Crossref, Google Scholar

Schwartz PJ, Brown C, Wehr TA, et al: Winter seasonal affective disorder: a follow-up study of the first 59 patients of the National Institutes of Mental Health Seasonal Studies Program. Am J Psychiatry 153:1028–1036, 1996Crossref, Google Scholar

Seeman MV: Interaction of sex, age, and neuroleptic dose. Compr Psychiatry 24:125–128, 1983Crossref, Google Scholar

Seeman MV: Current outcome in schizophrenia: women vs men. Acta Psychiatr Scand 73:609–617, 1986Crossref, Google Scholar

Seeman MV: The role of estrogen in schizophrenia. J Psychiatry Neurosci 21:123–127, 1996Google Scholar

Seeman MV: Gender differences in the prescribing of antipsychotic drugs. Am J Psychiatry 161:1324–1333, 2004Crossref, Google Scholar

Sheikh JI, Leskin GA, Klein DF: Gender differences in panic disorder: findings from the National Comorbidity Survey. Am J Psychiatry 159:55–58, 2002Crossref, Google Scholar

Silverman JG, Raj A, Mucci LA, et al: Dating violence against adolescent girls and associated substance use, unhealthy weight control, sexual risk behavior, pregnancy, and suicidality. JAMA 286:572–579, 2001Crossref, Google Scholar

Stewart DE, Boydell KM: Psychological distress during menopause: association across the reproductive life cycle. Int J Psychiatry Med 23:157–162, 1993Crossref, Google Scholar

Stewart DE, Robinson GE: Violence against women, in American Psychiatric Press Review of Psychiatry, Vol. 14. Edited by Oldham JM, Riba ME. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1995, pp 261–285Google Scholar

Szymanski S, Lieberman JA, Alvir JM, et al: Gender differences in onset of illness, treatment response, course, and biologic indexes in first-episode schizophrenic patients. Am J Psychiatry 152:698–703, 1995Crossref, Google Scholar

Task Force on Panic Anxiety and Its Treatments: Panic anxiety and panic disorder, in Panic Anxiety and Its Treatments: Report of the World Psychiatric Association Presidential Educational Task Force. Edited by Klerman GL, Hirschfield RMA, Weissman MM, et al. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1993, pp 3–38Google Scholar

Tondo L, Baldessarini RJ: Rapid cycling in women and men with bipolar manic-depressive disorders. Am J Psychiatry 155:1434–1436, 1998Crossref, Google Scholar

Vintzileos AM, Ananth CV, Smulian JC, et al: The impact of prenatal care in the United States on preterm births in the presence and absence of antenatal high-risk conditions. Am J Obstet Gynecol 187:1254–1257, 2002.Crossref, Google Scholar

Vintzileos A, Ananth CV, Smulian JC, et al: The impact of prenatal care on post-neonatal deaths in the presence and absence of antenatal high-risk conditions. Am J Obstet Gynecol 187:1258–1262, 2002.Crossref, Google Scholar

Walsleben JA: Does being female affect one’s sleep? J Womens Health Gend Based Med 8:571–572, 1999Crossref, Google Scholar

Walter H, Gutierrez K, Ramskogler K, et al: Gender-specific differences in alcoholism: implications for treatment. Arch Women Ment Health 6:253–258, 2003Crossref, Google Scholar

Wehr TA, Goodwin FK: Rapid cycling in manic-depressives induced by tricyclic antidepressants. Arch Gen Psychiatry 36:555–559, 1979Crossref, Google Scholar

Weissman MM, Leaf PJ, Holzer CE 3rd, et al: The epidemiology of depression: an update on sex differences in rates. J Affect Disord 7:179–188, 1984Crossref, Google Scholar

Weissman MM, Livingston MB, Leaf PJ, et al: Affective disorders, in Psychiatric Disorders in America: The Epidemiologic Catchment Area Study. Edited by Robins LN, Regier DA. New York, Free Press, 1991, pp 53–80Google Scholar

Wells JE, Bushnell JA, Hornblow AR, et al: Christchurch Psychiatric Epidemiology Study, Part I: methodology and lifetime prevalence for specific psychiatric disorders. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 23:315–326, 1989Crossref, Google Scholar

Wenger NK, Speroff L, Packard B: Cardiovascular health and disease in women. N Engl J Med 329:247–256, 1993Crossref, Google Scholar

Winokur G, Coryell W, Akiskal HS, et al: Manic-depressive (bipolar) disorder: the course in light of a prospective ten-year follow-up of 131 patients. Acta Psychiatr Scand 89:102–110, 1994Crossref, Google Scholar

Wisner KL, Wheeler SB: Prevention of recurrent major postpartum major depression. Hosp Community Psychiatry 45:1191–1196, 1994Google Scholar

Wittchen HU, Essau CA, von Zerssen D, et al: Lifetime and six-month prevalence of mental disorders in the Munich Follow-up Study. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 241:247–258, 1992Crossref, Google Scholar

Wohlfarth T, Storosum JG, Elferink AJ, et al. Response to tricyclic antidepressants: independent of gender? Am J Psychiatry 161:370–372, 2004Crossref, Google Scholar

Yehuda R: Post-traumatic stress disorder. New Engl J Medicine. 346:108–114, 2002Crossref, Google Scholar

Yonkers KA: The association between premenstrual dysphoric disorder and other mood disorders. J Clin Psychiatr 58 (suppl 15):19–25, 1997Google Scholar

Yonkers KA, Gurguis G: Gender differences in the prevalence and expression of anxiety disorders, in Gender and Psychopathology. Edited by Seeman MV. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1995, pp 113–130Google Scholar

Yonkers KA, Zlotnick C, Allsworth J, et al: Is the course of panic disorder the same in women and men? Am J Psychiatry 155:596–602, 1998Crossref, Google Scholar

Zerbe KJ: Anxiety disorders in women. Bull Menninger Clin 59 (2 suppl A):A38–A52, 1995Google Scholar