Does Switching to a New Antipsychotic Improve Outcomes? Data from the CATIE Trial

Abstract

Purpose:

Previous analysis of data from CATIE showed that patients randomly assigned to switch to a new medication were more likely to discontinue study drug than those who stayed on the medication they had been taking prior to randomization. This study addresses additional outcomes measures evaluating symptoms, neurocognition, quality of life, neurological side effects, weight, and health costs. First, considering patients randomized to olanzapine or risperidone, outcomes among patients who had been on the drug to which they were randomized prior to CATIE (N = 129 “stayers”) were compared to outcomes of those who switched to either of these two drugs (N = 269 “switchers”). A second set of analyses considered patients on baseline monotherapy with olanzapine (N = 297); risperidone (N = 252) or quetiapine (n = 87) and compared those randomly assigned to stay on each of these medications with those assigned to switch to any of the other five phase 1 medications in CATIE. In mixed models of each outcome the independent variable of primary interest represented stay vs. switch, with multivariate adjustment for potential confounding factors.

Results:

With one exception, there were no significant differences between stayers and switchers on any outcome measure in either set of analyses. The exception was that, in the second set of analyses, patients who stayed on olanzapine showed greater weight gain than those who switched from olanzapine to other drugs.

Conclusion:

Switching to a new medication yielded no advantage over staying on the previous medication. Staying on olanzapine was associated with greater weight gain.

(Reprinted with permission from Schizophrenia Research 2009; 107:22–29)

It is widely believed that patients who do not respond to one member of a psychotropic drug class or who experience troublesome side effects may have a better response to another agent in the same or similar class (Simon et al., 2005; Simon, 2001; Huskamp, 2003; Thase et al., 1997; Nurnberg et al., 1999; Institute of Medicine, 2001). Because of presumed variability in individual responsiveness, this has been thought to be true, even when the new drug has not been found to be superior to the old drug with respect to that outcome or side effect in head-to-head comparisons (Simon, 2001; Thase et al., 1997; Nurnberg et al., 1999; Institute of Medicine, 2001). The most frequently cited evaluations of this hypothesis have been based on non-experimental, observational data from patients who switched antidepressants, often with out any control group (Thase et al., 1997; Zarate et al., 1996; Brown and Harrison, 1995).

Such evaluations are generally inconclusive because they do not allow comparison of post-switch outcomes with outcomes that would have been observed if the medication had not been changed. One large review of outcomes after a medication change concluded that the greater the number of previous antidepressant trials (and by implication, drug failures), the lower the likelihood of response to a new treatment (Ruhe et al., 2006), a finding similar to those recently reported from the STAR-D trial (Rush, 2007).

Recent research on drug switching with antipsychotics has largely involved uncontrolled studies of switching to long-acting injectable risperidone (Fleischhacker et al., 2003; Taylor et al., 2004; Lamo et al., 2005). While these studies, along with several studies of switching among oral medications (Lamo et al., 2005; Kane et al., 2007) have shown improvement after a switch, in the absence of control groups that did not experience a medication change, they, too, remain inconclusive. While several recent reviews have addressed strategies and reasons for changing antipsychotic medications (Weiden, 2006; Remington et al., 2005) there has been only one study of switching, to our knowledge, that included a randomly assigned control group that did not switch medications (Essock et al., 2006).

That study used data from the Clinical Antipsychotic Trial of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) Schizophrenia trial in which patients were randomly assigned to one of five drugs and in which the primary outcome was time to all-cause discontinuation (Lieberman et al., 2005). Since most patients were on antipsychotic medications prior to the CATIE randomization, and these drugs were documented at the baseline assessment, the secondary stay-switch analysis was able to compare patients who were randomly assigned to stay on their prior medication with those who were randomly assigned to switch medications, using two different approaches (Essock et al., 2006). The first was anchored in the randomly assigned drugs and included individuals who had been randomly assigned to take olanzapine or risperidone in CATIE phase 1. These analyses compared patients who were randomly assigned to olanzapine or risperidone and had been taking the same drug prior to entering CATIE (“stayers”, N=139), and patients who were randomly assigned to olanzapine or risperidone as a new medication (“switchers”, N=496). This analysis found that switchers discontinued study drug more rapidly than those who were randomly assigned to stay on the medication they had been taking previously. The authors also noted that there were no differences between stayers and switchers on the PANSS total score, but did not examine other outcome measures.

A second set of analyses was anchored in the drug patients were taking before entering CATIE and examined the impact of being randomly assigned to either stay on the baseline monotherapy or switch to something different. This set of analyses examined all-cause discontinuation separately for patients whose baseline monotherapy was olanzapine (N=319), risperidone (N=271), or quetiapine (N=94) and revealed that, for individuals taking olanzapine monotherapy at baseline, there was a significant advantage of staying on olanzapine relative to switching to one of the other four double-blind treatments. In contrast, there were no statistically significant differences between stayers and switchers among those who were on either risperidone or quetiapine monotherapy at baseline (Essock et al., 2006). These analyses thus suggested that, on average, there may be no benefit associated with switching antipsychotics, and that, given early treatment discontinuation among switchers, there may be risks inherent in the process of switching.

Additional outcome measures are available from CATIE that address clinical outcomes such as PANSS subscales, depressive symptoms, quality of life, extrapyramidal side effects weight and health care costs. In the earlier stay-switch analyses, described above, the “switch”group included both patients who changed from one medication to another (52%) and patients who had been off medication altogether and who were presumably restarted on antipsychotic drug therapy after a hiatus of at least 2 weeks (48%). In order to address the clinical question of stay-or-switch for individuals already taking an antipsychotic medication, we, first, extracted from the original stay-switch analysis sample the sub-set of patients who reported taking monotherapy antipsychotic medication at the time of study entry.

A second set of stay-switch analyses, considers patients on olanzapine, risperidone, or quetiapine monotherapy at baseline with at least one follow-up assessment and compares, within each of these groups, those who were randomly assigned to stay on these medications with those who switched to any of the other medications to which random assignment was allowed in CATIE.

Thus, while the first set of analyses used patients randomly assigned to olanzapine or risperidone to define the sample, and compared those who had stayed on their prior medication to those who had switched to another medication, the second set of analyses uses the baseline monotherapy group to define each sample, and compares those randomly assigned to stay or switch, within each of these three groups.

METHODS

Study design

The CATIE trial was designed to compare the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of currently available atypical and conventional antipsychotic medications through a randomized clinical trial involving a large sample of patients treated for schizophrenia at multiple sites, including both academic and more representative community providers. Participants gave written informed consent to participate in protocols approved by local Institutional Review Boards. Details of the study design and entry criteria have been presented elsewhere (Stroup et al., 2003; Lieberman et al., 2005). CATIE was conducted between January 2001 and December 2004 at 57 U.S. sites. The diagnosis of schizophrenia was confirmed by the SCID (First et al., 1996). Patients were initially assigned to olanzapine, perphenazine, quetiapine, risperidone, or ziprasidone under double-blind conditions and treated with 1–4 identical capsules. Data on dosing have been presented previously (Lieberman et al., 2005). Patients who discontinued their first treatment were invited to receive other second generation antipsychotics, but data from these further randomizations are not used in this study.

Measures

Symptoms of schizophrenia were assessed with the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) (Kay et al., 1987) which yields a total average symptom score, based on 30 items rated from 1 to 7 (with higher scores indicating more severe symptoms), as well as subscales reflecting positive symptoms, negative symptoms and symptoms of general psychiatric distress.

Neurocognitive function was assessed with a composite battery of tests that were highly correlated and combined by z-scores into a single measure (Keefe et al., 2007).

Depression was assessed with the Calgary Depression Scale (Addington et al., 1996), and alcohol and drug use by the self reported Alcohol Use and Drug Use Scales (possible range: 1 to 5) (Drake et al., 1990).

Quality of life was assessed with the Heinrichs-Carpenter Quality of Life Scale (QOLS)(Heinrichs et al., 1984), a rater-administered scale that assesses overall quality of life and functioning on 21 items rated from 0 to 6 (with higher scores reflecting better quality of life) and the global item from the Lehman Quality of Life Interview which assesses overall quality of life on a seven-point sale that ranges from 1 (terrible) to 7 (delighted) (Lehman, 1988). General health related functioning was assessed with the mental and physical component scales of the SF-12 (Salyers et al., 2000).

Neurologic side effects were measured using 6 items of the Simpson-Angus EPS Scale (each scored 0–4) (Simpson & Angus, 1970); 4 items of the Barnes Akathisia Scale (Barnes, 1989), and the first 7 items from the AIMS measure of TD (addressing movements of specific body regions) (Guy, 1976). Weight was evaluated at the same time as other assessments were conducted.

Total health care cost was assessed with logarithmic transformation of total health costs as estimated using monthly self report data on inpatient, outpatient and residential psychiatric and medical services, and published unit cost data. Cost estimates were based on methods described elsewhere (Rosenheck et al., 2006).

Analysis

The first set of analyses focus on patients who had reported receiving antipsychiotic monotherapy immediately prior to study entry and were randomly assigned to either olanzapine (N=73 stayers, 126 switchers) or risperidone (N=56 stayers, 143 switchers) and completed at least one follow-up assessment. Of those randomly assigned to olanzapine, 73 (37%) had been on olanzapine prior to randomization, 54 (27%) on risperidone, 23 (12%) on quetiapine, and 49 (25%) on other antipsychotics. Of those assigned to risperidone, 69 (34%) had been on olanzapine prior to randomization, 56 (28%) on risperidone, 18 (9%) on quetiapine, and 56 (28%) on other antipsychotics. All data are from Phase 1 of CATIE.

The second set of analyses focused on patients on olanzapine, risperidone, or quetiapine monotherapy at baseline with at least one follow-up assessment and compares, within each of these groups, those who were randomly assigned to stay on these medications (N=73, 56 and 16 respectively) with those who switched to any of the other medications to which random assignment was allowed in CATIE (Ns=224, 196 and 71, respectively).

Both sets of analyses used mixed models to estimate the effect of staying vs. switching on the average value of the follow-up measures at all post-baseline follow-up assessments, with adjustment for potential confounding factors. Stay vs. switch was represented by a dichotomous variable and least square (i.e. adjusted) means of each dependent variable were compared across the two values of this dichotomous independent variable. Only observations during phase 1 of CATIE were included, i.e. while patients received the initial randomized drug (Stroup et al., 2003).

Other independent variables in the first set of analyses (in addition to the stay vs. switch dichotomous variable) included randomized treatment assignment (e.g. olanzapine vs. risperidone); the interaction of these two main effects (stay-switch by treatment); the baseline value of the dependent variable; a class variable representing time; and an interaction term representing the interaction of the baseline value of the dependent variable and time. The last term was used to adjust for differences in baseline characteristics among patients who remained in the trial for different periods of time. All phase one data were included as separate observations. To adjust standard errors for the correlation of observations from the same individual, mixed models were used in which a random subject effect was modeled with a first-order autoregressive covariance structure. All outcome measures were analyzed in the same way.

A further set of analyses tested the interaction of the stay-switch variable and time to evaluate differences in rates of change between stayers and switchers.

The second set of analyses included three separate subsets of analyses that separately considered patients on olanzapine monotherapy (N=297); risperidone monotherapy (N=252) or quetiapine montherapy (n=87) at baseline. Within each of these strats a dichotomous variable representing stay vs. switch was, again, used to compare the least square means across all time points of those who stayed on these baseline medications (25%, 22% and 18%, respectively) and those who were randomly assigned to switch to another medication (75%, 78% and 82%) using mixed models like those described above. Stay-switch by time interactions were also tested for significance.

Finally we replicated the previously published set of survival analyses (Essock. et al., 2006) in which time to all-cause discontinuation was the dependent variable to replicate previous findings in the data set that excluded patients who were not on antipsychotic monotherapy prior to entering CATIE.

Because, in the original report from CATIE, patients with TD were excluded from the randomization that included perphenazine, and ziprasidone was approved only after 40% of the sample was recruited, the original analyses were conducted within 4 different randomization strata (Lieberman et al., 2005). Because the three drugs that are of central interest in this secondary analysis (olanzapine, risperidone and quetiapine) were all in the same stratum (the randomization that allowed TD patients and that was available throughout the trial), stratified analyses were not necessary.

RESULTS

Baseline characteristics

At baseline the sample was 40.5 years old (sd=11.5), 73% male, 64% white, 31% black, 5% other, and 13.3% were Hispanic. The mean baseline score on the PANSS was 75.4 (sd=17.3), on the Heinrichs Carpenter scale 2.7(sd=1.03), and on the Lehman Quality of Life scale 4.3 (sd=1.32). The average weight was 194.6 lb (sd=3.5).

Comparison of stayers and switchers

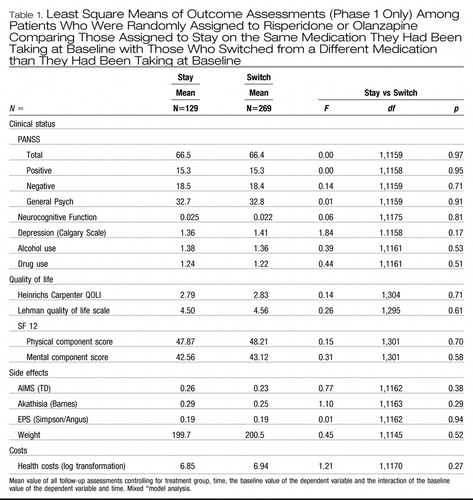

Comparisons of stayers and switchers among patients assigned to olanzapine or risperidone showed no significant differences on any outcome measure (Table 1). Differences between groups on PANSS total scores and on each subscale were less than 1% (Table 1). Comparison of interquartile ranges for adjusted PANSS outcomes (25%–75%) also showed minimal differences between groups (57.0–72.8 for stayers vs. 58.4–72.9) for switchers.

|

Table 1. Least Square Means of Outcome Assessments (Phase 1 Only) Among Patients Who Were Randomly Assigned to Risperidone or Olanzapine Comparing Those Assigned to Stay on the Same Medication They Had Been Taking at Baseline with Those Who Switched from a Different Medication than They Had Been Taking at Baseline

There were no significant interactions between treatment group assignment and stay-switch status for any outcome measures indicating that “staying” vs. “switching” similarly affected patients randomized to olanzapine and patients randomized to risperidone. No significant interactions were found between “stay-switch” group and time, indicating no difference in rates of improvement between these group.

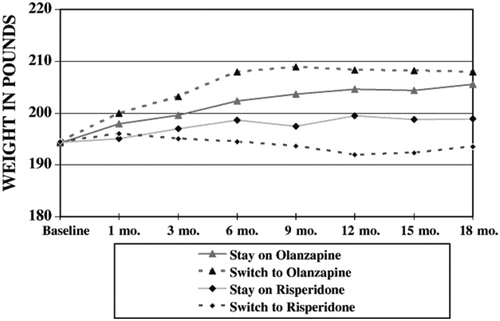

Further explorations of weight outcomes showed that although there was no overall differences between stayers and switchers on weight, consistent with previous findings (Lieberman et al., 2005), there was a highly significant difference between olanzapine and risperidone in average follow-up weight after controlling for baseline status (least square means across all outcome assessments = 203.4 lb on olanzapine vs. 196.7 lb on risperidone: F=29.6; df=1, 1145, p<.0001). However, the interaction of stay vs. switch and treatment on these two drugs reach did not reach statistical significance (F=2.17; df=1, 1145; p=0.14). To further examine these relationships we also evaluated a three-way interaction of stay vs. switch by treatment by time, which was also not significant, even at an more liberal alpha of p=.10 (F=1.45, df=12,1127; p=0.14). Graphic presentation these non-significant data show greater weight among both olanzapine groups than among either risperidone group (Fig. 1), and a trend towards a modest weight loss among patients who switched to risperidone. Thus while olanzapine lead to greater weight gain, there was no difference in weight gain whether one switched to olanzapine or stayed on olanzapine.

Figure 1. Weight by Stay-Switch Status and by Randomization to Risperidone or Olanzapine (least square means).

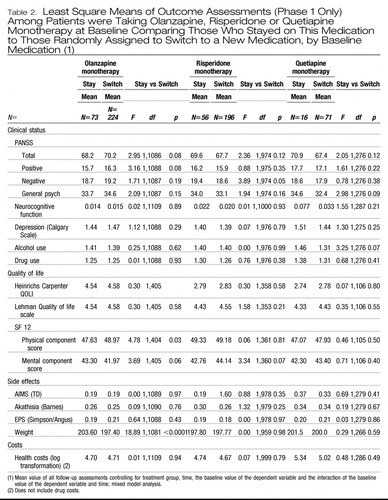

The second set of analyses, involving treatment groups defined by the monotherapy taken prior to study entry, also found no significant differences in the PANSS Total score with smaller than 5% differences between stayers and switchers within each monotherapy group or on most other outcomes (Table 2).

|

Table 2. Least Square Means of Outcome Assessments (Phase 1 Only) Among Patients were Taking Olanzapine, Risperidone or Quetiapine Monotherapy at Baseline Comparing Those Who Stayed on This Medication to Those Randomly Assigned to Switch to a New Medication, by Baseline Medication (1)

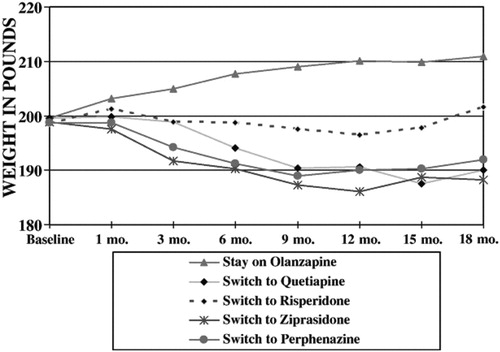

A highly significant difference in weight was found among patients previously treated with olanzapine such that those who switched to something else weighed significantly less than those who stayed on olanzapine. Further analysis of weight data showed a significant interaction between treatment assignment and time among patients treated with olanzapine prior to randomization (F=3.7;df=28,1041, p<.0001) with continuing weight gain among patients continued on olanzapine and weight loss within the other groups with the greatest weight loss among patients assigned to perphenazine and ziprasidone (Fig. 2). Again, this is not the result of staying on a drug vs. switching to another drug, but of a distinctive effect of olanzapine, such that being treated with this drug tends to increase weight, regard less of stay-switch status.

Figure 2. Weight by Stay-Switch Status only among patients treated with olanzapine prior to random assignment (least square means).

Two other statistically significant findings at p<.05 showed higher SF-12 physical component scores among patient who switched from olanzapine monotherapy (p=.03); and significantly lower PANSS negative scores among those who switched from risperidone monotherapy (p=0.049), but these findings are not clinically meaningful since they might be expected by chance in a table with a total of 51 comparisons.

Replication of proportional hazards analyses

As with the publication by Essock et al., (2006), proportional hazards models showed significantly lower likelihood of all cause discontinuation for patients who stayed on their previous medication (hazard ratio=0.60, p=.0006) and non-significantly greater likelihood for patients assigned to risperidone as compared to olanzapine (hazard ratio=1.24, p=.08). Duration of participation in phase 1 averaged 10.0 months: 11.9 months for stayers and 9.1 months for switchers. A model that only included patients assign to olanzapine showed significantly less risk of discontinuation for stayers (hazard ratio=0.53, p=.003); while a model including only patients assigned to risperidone showed a less robust hazard ratio that also favored stayers (hazard ratio=.69 p=0.07) but did not reach statistical significance. As in the original study interaction analysis of treatment group by switch status was not significant (p=35).

DISCUSSION

The analyses presented here extend those of a previous study of patients entering the CATIE trial that compared outcomes among those who stayed on their previous drug with those who switched to a different drug (Essock et al., 2006). We found no significant differences between stayers and switchers on measures of symptoms, neurocognition, depression, quality of life, neurological side effects or in costs in several sets of analyses, with the sole exception of weight gain. In the first set of analyses patients who were randomly assigned to olanzapine gained weight, regardless of whether they switched to olanzapine from another drug or stayed on it from before the CATIE randomization. A second set of analyses, limited to patients who were on olanzapine prior to randomization showed significantly greater weight gain on olanzapine among those who stayed on the drug as compared to those who switched to another drug, especially those who switched to ziprasidone, perphenazine or quetiapine who showed weight loss.

It is worth reiterating that the hypothesis we sought to evaluate was whether there are benefits from switching medications, even when there have been no differences between treatments in head-to-head trials. The pronounced weight gain with olanzapine was demonstrated in the original CATIE publication as in other studies, and confirmed here. CATIE data showing that switching off of olanzapine leads to substantial weight loss has not been previously presented.

Several strengths of the CATIE study are: a) treatment assignment was based on randomization; b) assessments were conducted under double blind conditions minimizing rater biases, c) the sample was relatively large, and d) extensive follow-up averaging over 9 months and including multiple post-baseline assessments make it unlikely that clinically meaningful differences between stayers and switchers would have remained undetected on the measures examined.

A potential limitation of the present analyses is that entry criteria for CATIE did not require that patients be unresponsive or refractory to their current medication, or even that they be in particular need of a medication change. If neither stayers nor switchers had any clinical need of a medication change, i.e. if they were optimally treated at baseline, one would not expect to see any difference in outcomes. However while this seems unlikely, since the mean baseline PANSS scores were similar to those of patients in other trials of antipsychotic medication in non-refractory samples, we do not have definitive data on the extent to which clinicians referred patients to CATIE who had responded well to their previous medication and thus has little further room for improvement during CATIE treatment.

A further limitation is that since information about the dose and duration of treatment with medications taken prior to randomization are not available we can not evaluate the adequacy of the trials with previous medications. In addition, we must note that these results only pertain to the treatments provided during the phase 1 randomization of CATIE and thus do not address the potential benefits of switching to clozapine which has been shown in other analyses, including one from CATIE (McEvoy et al., 2006) to offer specific effectiveness advantages in refractory schizophrenia.

The results of this study may seem counter-intuitive since one of the cardinal principals of clinical practice is that treatments should be tailored to the needs of each individual patient (Institute of Medicine, 2001) and that if one treatment is not effective, an alternative should be tried. If treatment responses are unique to each individual, they might not be demonstrable in any research study since the conclusions of empirical research are typically based on comparison of samples of individuals. It is notable that differences in the distribution of outcomes, as reflected by the inter-quartile ranges of the principal outcome measures, were as small as were differences in the least square means.

It is also possible, as suggested by this study, that switching medications does not yield consistently superior outcomes, but that clinical experience gives the somewhat misleading impression that drug switches have positive outcomes because real-world practice rarely, if ever, includes a comparable control group that does not switch medications. Although no differences between stayers and switchers were found here, significant improvement was observed over time on virtually all measures (Rosenheck et al., 2006). A clinician treating only switchers would have thus seen significant clinical improvement, as is typically reported in uncontrolled studies. However, the causal inference that the observed improvement was attributable to the change of medications would be unsupportable on the basis of such uncontrolled clinical experience. Observational studies, like those often cited as showing the benefits of medication changes, almost always show improvement with time. But since these studies lack comparable control groups their results most likely reflect, among other things, the non-specific effects of non-drug treatment and support; as well as regression to the mean. Patients who agree to participate in research studies are generally dissatisfied with their treatment and thus enter studies at times when they are doing poorly and thus may be especially likely to show improvement with the passage of time.

As suggested by the results of STAR*D, in which one-third of patients responded to the first treatment but only 10% responded to the fourth (Rush, 2007), patients who are unresponsive to one treatment may be more likely to be unresponsive to subsequent treatments, although some will show improvement. In the absence of random assignment to “stay” or “switch”, whether improvement with subsequent treatments represents a fresh treatment effect or simply the further passage of time and/or regression to the mean cannot be determined. The analysis presented here and the original study of which it is an extension are among the few to evaluate stay vs. switch interventions using data from an experimental double-blind design.

There are some circumstances in which a switch is clearly indicated, as when an unacceptable side effect emerges, such as weight gain, that is well-demonstrated to be associated with some treatments more than others (Newcomer, 2005). It would certainly be premature to discourage switching in general, although these results may argue for greater appreciation of “watchful waiting”as a clinical strategy. It is also possible that low medication adherence in real world practice masks important differences between drugs as well as the benefits of trying something new (Swartz et al., 2008).

This study extended the findings of a previous analysis of data from the CATIE trial, by Essock et al., to compare additional outcomes of patients who stayed on their prior medications and those who switched to a new medication. On measures of symptoms, side effects, quality of life and cost we found no significant benefit or risk for switching to a new medication in comparison to staying on the previous medication, with the sole exception that greater weight gain was observed among patients who stayed on olanzapine, reflecting well established pharmacology that distinguishes this drug from the others examined in this study.

Addington, D., Addington, J., Maticka-Tyndale, E., 1996. A depression rating scale for schizophrenics. Schizophrenia Research 3, 247–251.Crossref, Google Scholar

Barnes, T.R.E., 1989. A rating scale for drug induced akathisia. British journal of psychiatry 131, 222–223.Google Scholar

Brown, WA., Harrison, W., 1995. Are patients who are intolerant to one serotonin selective reuptake inhibitor intolerant to another. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 56(1), 30–34.Google Scholar

Drake, RE., Osher, F.C., Noordsy, D.L., Hurlburt, S.C., Teague, G.B., Beaudett, M.S., 1990. Diagnosis of alcohol use disorders in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 16(10), 57–67.Crossref, Google Scholar

Essock, S.M., Covell, N.H., Davis, S.M., Stroup, S.S., Rosenheck, R.A., Lieberman, J.A., 2006. Effectiveness of switching antipsychotic medications. American Journal of Psychiatry 163(12), 2090–2095.Crossref, Google Scholar

First, M.B., Spitzer, R.L., Gibbon, M.B., Williams, J.B., 1996. Structured Clinical Interview for Axes I and II DSM IV Disorders - Patient Edition (SCID-I/P). Biometrics Research Institute, New York State Psychiatric Institute, New York.Google Scholar

Fleischhacker, W.W., Eerdekens, M., Karcher, K., Remington, G., Llorca, P.M., Chrzanowski, W., Martin, S., Gefvert, O., 2003. Treatment of schizophrenia with long-acting injectable risperidone: a 12-month open-label trial of the first long-acting second-generation antipsychotic. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 64 (10), 1250–1257.Crossref, Google Scholar

Guy, W., 1976. Abnormal involuntary movements. In: Guy, W (Ed.), ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharamcology. National Institute of Mental Health, Rockville, MD (DHEW No. ADM 76–338).Google Scholar

Heinrichs, D.W., Hanlon, E.T., Carpenter, W.T., 1984. The quality of life scale: an instrument for rating the schizophrenic deficit syndrome. Schizophrenia Bulletin 10, 388–398.Crossref, Google Scholar

Huskamp, H.A., 2003. Managing psychotropic drug costs: will formularies work. Health Affairs 22 (5), 84–96.Crossref, Google Scholar

Institute of Medicine, Committee on Quality of Health Care in America, 2001. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. National Academy Press, Washington, D.C.Google Scholar

Kane,J.M., Meltzer, H.Y., Carson, W.H., McQuade, R.D., Marcus, R.N., Sanchez, R., for the Aripiprazole Study Group, 2007. Aripiprazole for treatment-resistant schizophrenia: results of a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, comparison study versus perphenazine. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 68 (2), 213–223.Crossref, Google Scholar

Kay, S.R., Fiszbein, A., Opler, L, 1987. The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 13, 261–276.Crossref, Google Scholar

Keefe, R.S.E., Bilder, R.M., Davis, S.M., Harvey, P.D., Palmer, B.W., Gold, J.M., Meltzer, H.Y., Green, M.F., Capuano, G., Stroup. T.S., McEvoy, J.P., Swartz, M.S., Rosenheck, R.A., Perkins, D.O., Davis, C.E., Hsiao, J.K., Lieberman, J.A., for the CATIE Investigators and the Neurocognitive Working Group, 2007. Archives of general psychiatry 64, 633–647.Crossref, Google Scholar

Lamo, I., de Naver, A., Windhager, E., Irmansyah, F., Lindenbauer, B., Rittmansberger, G., Platz, T., Jones, A.M., Altman, C., 2005. Efficacy and tolerability of quetiapine in patients with schizophrenia who switched from haloperidol, olanzapine or risperidone. Human Psychopharmacology: Clinical and Experimental 20 (8), 573–581.Crossref, Google Scholar

Lehman, A., 1988. A quality of life interview for the chronically mentally ill. Evaluation and Program Planning. 11, 51–62.Crossref, Google Scholar

Lieberman, J.A., Stroup, S., McEvoy, J., Swartz, M., Rosenheck, R., Perkins, D., Keefe, R.S.E., Davis, S., Davis, C.E., Hsiao, J., Severe, J., Lebowitz, B., 2005. for the CATIE investigators, 2005. Effectiveness of antipsychotic drugs in patients with chronic schizophrenia: primary efficacy and safety outcomes of the clinical antipsychotic trials of intervention effectiveness (CATIE) schizophrenia trial. New England Journal of Medicine 353 (12), 1209–1223.Crossref, Google Scholar

McEvoy,J.P., Lieberman, J.A., Stroup, T.S., Davis, S.M., Meltzer, H.Y., Rosenheck, R.A., Swartz, M.S., Perkins, D.O., Keefe, R.S.E., Davis, CE., Severe, J., Hsiao, J.K., for the CATIE Investigators, 2006. Effectiveness of clozapine versus olanzapine, quetiapine, and risperidone in patients with chronic schizophrenia who did not respond to prior atypical antipsychotic treatment. American Journal of Psychiatry 163, 600–610.Crossref, Google Scholar

Newcomer, J., 2005. Second-generation (atypical) antipsychotics and metabolic effects: a comprehensive literature review. CNS Drugs 19 (Suppl 1), 1–93.Crossref, Google Scholar

Nurnberg, H.G., Thompson, P.M., Hensley, P.L., 1999. Antidepressant medication change in clinical treatment setting: a comparison of the effectiveness of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 60 (9), 574–579.Crossref, Google Scholar

Remington, G., Chue, P., Stip, E., Kopala, L, Girard, T. and Christensen, B., 2005. The crossover approach to switching antipsychotics: what is the evidence. Schizophrenia Research 76(203) 267–272.Crossref, Google Scholar

Rosenheck, R.A., Leslie, D., Sindelar, J., Miller, E.A., Lin, H., Stroup, S., McEvoy, J., Davis, S., Keefe, R.S.E., Swartz, M., Perkins, D., Hsiao, J., Lieberman, J.A., 2006. Cost-effectiveness of second generation antipsychotics and perphenazine in a randomized trial of treatment for chronic schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry 163 (12), 2080–2089.Crossref, Google Scholar

Ruhe, H.G., Huyser, S., Swinkels, J.A.S., Schene, A.H., 2006. Switching antidepressants after a first selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor in Major depressive disorder: a systematic review. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 67 (12), 1836–1855.Crossref, Google Scholar

Rush, A.J., 2007. STAR*D What have we learned. American Journal of Psychiatry 164(2), 201–204.Google Scholar

Salyers, M.P., Bosworth, H.B., Swanson, J.W., Lamb-Pagone, J., Osher, F.C., 2000. Reliability and validity of the SF-12 health survey among people with severe mental illness. Medical Care 38 (11), 1141–1150.Crossref, Google Scholar

Simpson, G.M., Angus, J.W.S., 1970. A rating scale for extrapyramidal side effects. Acta Psychiat Scand (Suppl 212), 11–19.Google Scholar

Simon, G.E., 2001. Choosing a first-line antidepressant. Equal on average does not mean equal for everyone. JAMA 286(23), 3003–3004.Crossref, Google Scholar

Simon, G.E., Psaty, B.M., Hrachovec, J.B., 2005. Mora M. Principles for evidence-based drug formulary policy. Journal of General Internal Medicine 20(10), 964–968.Crossref, Google Scholar

Stroup, T.S., McEvoy, J.P., Swartz, M.S., Byerly, M.J., Glick, I.D., Canive, J.M., McGee, M.F., Simpson, G.M., Stevens, M.C., Lieberman, J.A., 2003. The National Institute of Mental Health Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) project: schizophrenia trial design and protocol development. Schizophrenia Bulletin 29(1), 15–31.Crossref, Google Scholar

Swartz, M.S., Wagner, H.R., Swanson, J.W., Stroup, T.S., McEvoy, J.P., Reimherr, F., Miller, D.D., McGee, M., Khan, A., Canive, J.M., Davis, S.M., Hsiao, J.K., Lieberman, J.A., 2008. The effectiveness of antipsychotic medications in patients who use or avoid illicit substances: results from the CATIE study. Schizophrenia Research 100(1–3), 39–52.Crossref, Google Scholar

Taylor, D.M., Young, C.L., Mace, S., Patel, M., 2004. Early clinical experience with risperidone long-acting injection: a prospective, 6-mnth follow-up of 100 patients. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 65 (8), 1076–1083.Crossref, Google Scholar

Thase, M.E., Blomgren, S.L., Birkett, M.A., Atewr, J.T., Tepner, R.G, 1997. Fluoxetine treatment of patients who failed initial treatment with sertraline. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 58 (1), 16–21.Crossref, Google Scholar

Weiden, P.J., 2006. Switching antipsychotics: an updated review with a focus on quetiapine. Journal of Psychopharmacology 20 (1), 104–108.Crossref, Google Scholar

Zarate, CA, Kando,J.C., Tohen, M., Weiss, M.K., Cole, J.O., 1996. Does intolerance or lack of response with fluoxetine predict the same will happen with sertraline. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 57 (2), 67–71.Google Scholar