The Temperament and Character Inventory in Addiction Treatment

Abstract

This article provides an

There is a growing trend to promote wellness within a context of an integrative mental health care paradigm and increasing evidence for the effectiveness of a broad array of alternative treatment modalities. These modalities include mind-body interventions such as meditation and spiritual counseling as well as an emphasis on exercise, diet, and life style changes. A body of research supports the efficacy of many of these approaches, especially in treating addictions. A voluminous review of the literature by Geppert, Bogenschutz, and Miller (1) demonstrated reduced substance use among those practicing meditation and the protective effects of 12-step group involvement during recovery. This integrative mental health paradigm does not diminish the importance of medications and traditional therapeutic approaches but rather can enhance and supplement them. Furthermore, a respect for the benefits and contributions of Alcoholics Anonymous and other 12-step groups needs to be acknowledged and their critical role in abstinence-based programs (often referred to as the “Minnesota model”) needs to be maintained while other evidence-based approaches to improve outcomes are being explored. There also needs to be a closer alliance with the Minnesota model programs and psychiatrists in the community who manage so many patients with comorbidity.

“Continued use of mood-altering addicting substances despite adverse consequences” is an accepted definition of addiction (2). More recently, certain behaviors such as compulsive gambling, some eating disorders, and compulsive sexual acting out have been seen as addictions having common pathways such as deficits in the dopamine- and endorphin-mediated reward pathway of the brain (3–5). These conditions can present with an intensified experience of the substance or behavior, along with deficits in motivation, learning, memory, and decision-making (6). Substance abuse and dependence constitute a major and growing health problem (7). It is estimated that 24 million people in the United States need treatment for an addiction, with only 2.5 million receiving it (8).

Despite this valuable understanding of the biological underpinnings of this disease and subsequent progress in medication strategies, psychosocial interventions are the mainstay of addiction treatment. There exists today an emphasis on addiction treatment to enhance psychosocial interventions with holistic and integrative approaches. This includes exploring personality styles and their role in guiding integrative treatment plans.

THE MINNESOTA MODEL

A prevalent addiction treatment approach and the one this program uses is often referred to as the Minnesota model. This model has a rich history of utilizing a holistic and integrative approach to alcoholism and other addictions. The Minnesota model has its origins in partnering with Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) in the early 1950s and included a psychobiological approach to addictions. This approach centered on a multidisciplinary team that included recovering alcoholics and an integration of the tenets of AA into the treatment process. Because the AA program has an emphasis on the spiritual aspects of recovery, AA has become an essential element of the treatment. The Minnesota model is descended from a legacy that began with the advent of 12-step recovery such as AA, which had its beginning in 1935. According to Damian McElrath, as described in the Journal of Psychoactive Drugs (9) the contribution of AA to the Minnesota model is the following: 1) the knowledge or belief that alcohol is a physical, mental, and spiritual illness; 2) the 12 steps that outline the problem, the solution, and the spiritual exercises needed to live in the solution; and 3) the fellowship or recovery that takes place with one alcoholic talking to another. He goes on to describe the essential elements included in the Minnesota model: recognizing the importance of 12-step recovery within an abstinence-based program, as well as a multidisciplinary treatment approach within a therapeutic community. Khantzian and Mack (10) reinforced the importance of the psychosocial support of a therapeutic community in the treatment of addictions. They state, “Alcohol and drug dependence are the result of complex interactions of biological, psychological, and cultural factors; yet, the most promising and successful interventions in these disorders are psychosocial in nature.” The essential elements of psychosocial support in a therapeutic community include the ability for support from other addicts and alcoholics within the framework of either a residential setting, day hospital setting, and even, although to a lesser degree, an intensive outpatient setting. This psychosocial support is not necessarily inconsistent with the growing awareness of the reward circuitry of the brain and its role in addiction.

Although AA and treatment separated rather early in the process, the connection between them remains vital for everyone who ascribes, in some form, to this model. Involvement in this model of treatment with aftercare and ongoing AA involvement has shown positive results (11). Most 12-step oriented treatment programs recognize the importance of identifying and treating both psychiatric issues in the addict and substantial psychiatric comorbidity. Despite these advances, there continues to be a need to integrate ways in which to better identify psychiatric issues in addicted patients and improve communication with treating psychiatrists in the community and treatment providers. This is particularly critical in the identification of personality dynamics in addicted patients. This article describes a collaboration that evolved from the utilization of a personality self-report [Temperament and Character Inventory-Revised (TCI-R)] in an addiction program for professionals and its positive impact on the patients and the clinicians. This emphasis on personality dynamics is integrated into an existing Minnesota model program including correlation with the steps of AA.

PERSONALITY AND ADDICTION

A study published in the American Journal of Psychiatry revealed that 60% of subjects with substance use disorders had personality disorders (12). Others observed that 78% of the patients interviewed had at least one personality disorder, and the average number of personality disorders was 1.8 per patient (13) and was even higher (91%) in the patients who met the criteria for one personality disorder in drug-dependent people; however, no single addictive personality emerged. This result was confirmed by any number of researchers. However, these high percentages illustrate that there is significant importance in recognizing personality dysfunctions and styles in treating addiction.

There are a number of different views regarding personality and addiction. A primary substance use disorder model postulates that substance abuse contributes to the development of personality pathology. Three mechanisms regarding personality and addiction are proposed. First, substance abuse often occurs within the context of a deviant peer group and antisocial behaviors might be shaped and reinforced by social norms (the social learning hypothesis). Second, some Cluster A traits (such as suspiciousness, magical thinking, and eccentric behaviors), Cluster B traits (such as exploitativeness, egocentrism, and manipulativeness), and Cluster C traits (such as passivity and social avoidance), may be shaped and maintained by reinforcing and conditioning properties of the substances (behaviorist learning hypothesis). Third, chronic substance abuse may alter personality through neuroadaptive changes (the neuropharmacological hypothesis). However, it is unclear to what extent these effects can override or interact with preexisting personality patterns to form new personality configurations (14).

A primary personality disorder model suggests that comorbid relationships with pathological personality traits contribute to the development of a substance abuse disorder. There is some evidence to support this model in specific instances, particularly in regard to antisocial personality disorder, as well as borderline personality disorder. Several studies suggest that individuals scoring high on traits such as antisociality and impulsivity and low on constraint or conscientiousness have lower thresholds for deviant behaviors, such as alcohol and drug abuse (14). This model suggests that there are three major types of pathways within the primary personality disorder model: the behavioral disinhibition pathway, the stress reduction pathway, and the reward sensitivity pathway. Individuals with personality disorders appear to have a higher lifetime prevalence of alcoholism and other addictions (15). Patients with two particular personality disorders, antisocial personality disorder and borderline personality disorder, have been suggested to have the highest prevalence of addiction (16): as high as 64% for borderline personality disorders and 54% for other personality disorders. Borderline personality disorders were significantly associated with current substance use disorders, excluding alcohol and cannabis, and with lifetime alcohol, stimulant, and other substance use disorders, excluding cannabis. Antisocial personality disorder was associated with lifetime substance use disorders other than alcohol, cannabis, and stimulants (17). Cloninger's type 1 and type 2 subtypes reflected late and early age of onset and related trait characteristics for each type, predominantly in male participants. Early-onset alcoholism (type 1) was defined as occurring at age <25 years and late-onset alcoholism (type 2) as occurring at age >25 years of age. High novelty seeking and low harm avoidance were predictive of early onset with progressive daily use pattern or type 2 alcoholism (18).

Finally, there is a common factor model which assumes that both personality pathology and substance abuse are linked to an independent third factor that contributes to the development of both disorders. This model is more likely for personality disorders that show relatively high joint comorbidity and occur with substance dependence.

Several studies demonstrated convincingly that personality pathology is associated with pre- and posttreatment problem severity but is not a robust predictor of the amount of improvement. Other studies suggested that chronicity and personality disorder rank as important characteristics associated with addiction severity (19). Use of a multifactorial approach to understanding the personality dynamics of persons with addictions mandates that caution be demonstrated in assessing patients for comorbid personality disorders. At least some of the patient's maladaptive behaviors may be the result of the ingestion of substances or withdrawal from substance use, which can complicate the assessment of comorbid axis I and axis II disorders.

THE ADDICTIVE PERSONALITY

There have been many discussions regarding addictive personality; however, research indicates that the personalities of alcoholics are heterogeneous. For example, Nathan (20) stated that the addictive personality consists of the behaviors of the addict, in other words axis II traits. However, according to Nathan and others, it is important to recognize that personality disorders commonly occur secondarily to substance use disorders and must be distinguished from a primary personality disorder.

Certain problems with impulsivity or overall poor coping skills within a personality structure can occur as a result of problems in early development. However, looking at personality and addiction can also be somewhat confusing because addiction can create deficits in personality; that is, addiction can interfere with the way people see themselves, cope with stress, and interact with other human beings. It becomes a chicken and egg problem that sometimes cannot be completely discerned until someone is sober for an extended period of time. Learning about the patient's personality structure, especially as influenced by addiction, is an important task for both patient and therapist.

An interesting area of study involves comparing the “parkinsonian personality” to those traits often associated with addiction, such as high novelty seeking and impulsivity. Dagher and Robbins (21) describe what happens to patients with Parkinson's disease when they abuse their medication. The parkinsonian personality has been characterized as rigid, introverted, and slow-tempered well before the onset of motor symptoms. Usually, a history of tobacco and alcohol abstinence is also noted, and generally there is a low incidence of drug addiction. Parkinson's disease is characterized by a deficiency in dopamine levels with treatment including dopaminergic medications. In rare instances, patients have side effects from high dopamine levels which have included compulsive behaviors such as compulsive gambling, hypersexuality, and even abuse of and addiction to their Parkinson's disease medications.

From a psychological perspective, Khantzian and Mack (10) have described “the heavy reliance on chemical substances to relieve pain, provide pleasure, regulate emotions and create personality cohesion.” They have described this process as “self-governance,” and although no specific “addictive personality” may be identifiable, the maladaptive personality functioning in addiction creates a need for a cohesive sense of self and strategies to enhance self-governance capabilities.

It would be unrealistic to think that deficits in the neurochemistry and reward circuitry in addiction, such as dopamine synthesis, would not influence personality functions in addicted patients. It has been speculated that these same circuits evolved in the brain for purposes of social attachment and are activated in addiction (22). It seems logical that the strong connection that can occur between sober addicts plays such a pivotal role in addiction recovery. Conversely, disorders that disrupt these attachment and affiliative systems, such as borderline personality disorder (23), can pose significant challenges in the treatment of those who have addiction complicated by these disorders. In all probability, there are adaptive styles that occur at different times in the addictive process. Before the addiction, a deficit in reward capacity could create a feeling of deprivation, leading to craving states and mood instability. This would certainly be the case in an exaggerated way during active addiction withdrawal and craving. During active substance use, exaggeration of previous temperament styles will certainly be present, and, as a result of the ongoing addiction, character development would be arrested.

Although there is no evidence for a single addictive personality, there are a multitude of ways personality functioning affects addiction and treatment outcomes. Despite the contradicting factors of personality and its effect on addiction and prognosis, it is critical to recognize the effects of personality on addiction when a treatment plan is developed. This article will provide an overview of how a program, primarily focused on addicted high-accountability professionals, uses various aspects of personality in an attempt to individualize treatment plans while continuing the traditions of an AA-oriented, abstinence-based, therapeutic community.

PERSONALITY ASSESSMENT IN ADDICTION TREATMENT

Individualized treatment plans are a crucial element in the provision of optimal care for patients. The Institute of Medicine released a report titled “Improving the Quality of Health Care for Mental and Substance-Use Conditions” that identified six aims of high-quality health care, stating that it should be safe, effective, patient-centered, timely, efficient, and equitable. One recommendation is that clinicians and organizations providing mental and substance use treatment should “increase their use of valid and reliable patient questionnaires or other patient-assessment instruments that are feasible for routine use to assess the progress and outcomes of treatment systematically and reliably (24). Gaining insights into personality variables of addicted patients with the use of the TCI-R has facilitated greater patient collaboration in the individualized treatment planning process and provides an opportunity for a more detailed assessment of patient programs and outcomes.

The TCI-R has four temperament and three character dimensions. The temperament dimensions are Novelty Seeking, Harm Avoidance, Reward Dependence, and Persistence. The character dimensions are Self-Directedness, Cooperativeness, and Self-Transcendence. Temperament tends to represent more automatic responses; character, in contrast, is learned. Each of these dimensions has several subscale measures that further describe each dimension. Cloninger (25) used a psychobiological model of personality in the construction of the TCI-R. He stated that the “temperament traits manifest early in life, and involve preconceptual biases in perceptual memory and habit formation, involving habits and skills that are elicited by simple stimuli perceived by the physical senses and changing little with increasing age, with psychotherapy, or with pharmacotherapy.”

Character is what one makes of himself or herself intentionally (26). Cloninger et al. (27) stated that character traits mature in adulthood and influence personal and social effectiveness by insight learning about self-concepts. Self-concepts vary according to the extent to which a person identifies the self as (1) an autonomous individual, (2) an integral part of humanity, and (3) an integral part of the universe as a whole (27). The TCI-R has been researched in terms of its utility in providing indicators of personality disorders and other psychological disorders. In these studies, low scores on the character dimensions of Self-Transcendence and Cooperativeness correlate with a high symptom count for personality disorders. Character traits are used to diagnose the presence and severity of a disorder, whereas temperament traits indicate differential personality diagnoses (28). For example, the combined temperament profile of a high score in Novelty Seeking and low scores on both Harm Avoidance and Reward Dependence suggest the potential for antisocial traits. The individual with this combination of scores would tend to be impulsive, engaging easily in unfamiliar situations and disengaging angrily when frustrated, carefree in attitude, and not motivated to establish or maintain warm human relationships. Temperament dimensions can be indicative of the cluster of personality disorder in that low scores on Reward Dependence suggest Cluster A (odd), high scores on Novelty Seeking suggest Cluster B (impulsive), and high scores on Harm Avoidance suggest Cluster C (anxious) personality disorders. According to Cloninger and colleagues (29), personality disorders are defined in terms of a “configural profile of genetically independent dimensions.”

The TCI-R has also been used in a number of studies for its predictive value in substance-dependent populations. For example, Arnau et al. (30) noted that patients who abandoned treatment had lower scores in Cooperativeness and that for those with higher scores in Self-Directedness and Cooperativeness, length of time until the abandonment of treatment was greater. Patients with scores higher than 50 on personality scales of Persistence, Self-Directedness, and Cooperativeness stayed in treatment longer and had better treatment outcome (30).

A computerized report for the TCI-R is available for patients and suggests several temperament and character types. For example, someone high in Novelty Seeking, low in Harm Avoidance and high in Reward Dependence can be described as passionate. If they are high in all three character dimensions, he or she is described as creative.

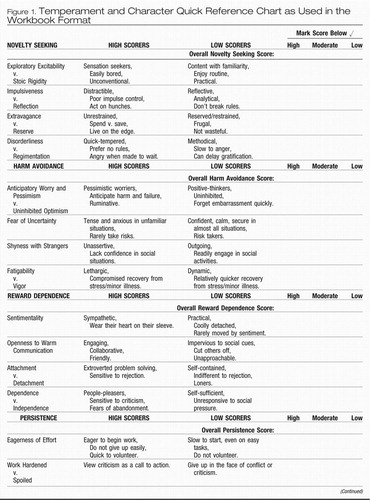

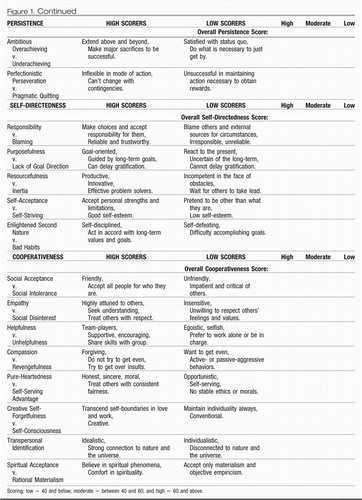

A manual that uses the subscales of the TCI-R has been developed for this program. This allows closer evaluation of specific temperament and character aspects of personality. For example, in regard to temperament, one individual may have an overall high score in Novelty Seeking, but the subscales suggest that he or she is highest in the impulsivity subscale of this dimension and relatively low in the exploratory subscale. In the Reward Dependence dimension, he may be high in the dependence subscale but low in attachment. The tension between these subscales can be a targeted area in treatment planning that may include vulnerabilities toward certain automatic responses that can potentially trigger relapse. In an example of character dimension subscale exploration, this same individual may have a high score in the Self-Directedness subscale of responsibility, suggesting an acceptance of his or her addiction and a low score in the subscale of resourcefulness, indicating a lack of confidence in having the ability to overcome it. The treatment team can work with these constellations in targeting multiple and often conflicting self-concepts as elucidated through the TCI-R in targeted ways that can facilitate the recovery process. A reproduction of a handout for patients being treated in this program which shows the TCI-R subscale checklist that is transferred by the patient from the computerized TCI-R report is shown in Figure 1.

Patients in this program who have taken the TCI-R are asked to choose which strengths and weaknesses they most agree with in the subscale dimensions and enter them into a flowchart diagram called a “collage.” The collage includes identification of what they are looking for in the addiction, what gives them satisfaction, and the various triggers and strategies that need attention for character growth and relapse prevention. Because patients have unique personality configurations and motives for use, this tool creates an opportunity for individualized treatment planning. The unique adaptive personality style of each patient is essential in the understanding of what drives their addiction and what will encourage their recovery. The TCI-R is repeated at the end of treatment to measure changes in these dimensions and subscales. A second set of collages are completed to examine how these changes impact their initial progress in recovery. This manual-driven approach allows for robust discussion in individual and group sessions, as well as within the therapeutic community.

Vignette

Ellen is a 36-year-old female divorced E.R. nurse admitted for hydrocodone dependence. She was discovered at work diverting patient medications for her own use. She had a history of physical abuse from an alcoholic father. This was her first treatment program for chemical dependence, but she had a long history of individual psychotherapy and two previous psychiatric admissions for suicide attempts, the last being 7 years before this admission. Her diagnosis on admission included dysthymic disorder and major depression, recurrent. She started her drug abuse 1 year before admission, so it was clear that her coexisting psychiatric conditions preceded her addiction. She had a substantial family history of alcohol and other substance abuse and dependence.

She was euthymic on admission, as her mood disorders were adequately treated on an outpatient basis before admission. She described a recent lower back injury that occurred on the job as precipitating her hydrocodone use. She was able to recognize that she continued to use the drug in increasingly higher amounts despite adverse consequences. She also recognized that she used hydrocodone for the euphoric effect and not pain relief as time went on. Her low back pain responded well to physical therapy and intermittent anti-inflammatory medications.

She struggled with making a connection with other patients in the therapeutic community. Her tendency was to be moody, quarrelsome, and envious. She frequently complained about her roommates, would become hostile toward them, and later expressed remorse. She initially exhibited these patterns at AA meetings as well. She consistently was late with her program assignments.

|

|

Her TCI-R scores indicated she was high on Novelty Seeking, Harm Avoidance, and Reward Dependence. This configuration suggested that she had an approach-avoidant manner of dealing with relationships. She scored in the average range on Self-Directedness and Self-Transcendence but very low on Cooperativeness, especially in the subscale of social acceptance. She had a high score in helpfulness, which was also consistent with her commitment to patient care as a nurse.

Her treatment plan emphasized improving her understanding of the conflicts she had in the therapeutic community. With the help of staff and other patients, Ellen was able to recognize how her pattern of social intolerance created tension in her life, including activation of her approach-avoidant temperament. This was also a trigger for substance use. Because of Ellen's capacity for helpfulness, she was able to develop strong friendships in the program. Ellen's repeat TCI-R at the end of treatment included a significant increase in her social acceptance score.

The above vignette is an example of how the TCI-R was able to inform a specific treatment plan and assist in targeting personality variables and how they played out in the therapeutic community. The patient, able to work with her own TCI-R, was able to feel part of the treatment planning process.

The ability to make improvement in one component of personality (like social intolerance for Ellen) can promote strength in other areas. This is what Cloninger (25) referred to as the coherence principle or interconnectedness of thought and personality. Cloninger also stated that character traits of Self-Directedness and Cooperativeness are positively correlated in a manner that the development of one facilitates the development of the other. He stated that the development of Self-Transcendence is associated with greater life satisfaction and positive emotions for all possible configurations of Self-Directedness and Cooperativeness. Hence, the development of all three character traits is important for healthy integration of personality and lasting satisfaction with life. According to Cloninger, the adaptive nature of personality suggests the presence of an optimization principle as personality develops and that the self-organization of personality requires the satisfaction of multiple and sometimes conflicting constraints that require a self-transcendent shift in perspective (25).

TCI-R AND 12-STEPS OF AA

The achievement and maintenance of sobriety is both the primary and continuing goal of each patient with an addictive disorder, and extensive research has shown that active participation in 12-step recovery programs is highly effective in the maintenance of sobriety (31). Initial philosophies of therapeutic interventions were that the addictive behaviors would cease as a function of psychological healing, typically of a psychodynamic nature. The second evolution of treatment for addictions involved the use of 12-step groups and the philosophies of a disease model of addictions and a focus on group therapy and therapeutic community interventions. The tenets of the program discussed in this article, as well as current movements in the field of addiction psychiatry and psychology, give credence to the success of combined continual participation in AA or other 12-step groups for all patients in recovery, coupled with participation in individual, group, or couples counseling.

AA recognized the importance of addressing personality issues. In the book Twelve Steps and Twelve Traditions (32), it is stated “we reluctantly come to grips with those serious character flaws that made problem drinkers of us in the first place, flaws which must be dealt with to prevent a retreat into alcoholism once again.”

AA or other 12-step groups provide an effective structure for the patient to approach recovery as well as collaborative connections with other individuals with an addictive disorder. Recovery groups are deemed most effective if some of the members have a long history of sobriety to provide leadership for other members. Newcomers and persons early in the recovery process can also provide fresh levels of insight as well. These individuals serve as a reminder of the ongoing struggle of managing addictive diseases to those with longer time in recovery. Patients in the program are encouraged to participate actively in AA or other 12-step meetings and to seek out a sponsor. There is also correlation with the steps of AA, which is seen as critical in encouraging the patient to understand the connections between the therapeutic work done in treatment and his or her ongoing 12-step work. However, the program is sensitive to the need of separation between 12-step programs and treatment facilities. It also recognizes the autonomous nature of the 12-step sponsor/recovering addict relationship, offering only suggestions of which steps to prioritize. Although there is a linear progression of the 12 steps, each patient in treatment may be at a different point in the evolution of his or her recovery and therefore needs to emphasize some steps over others. For example, this could apply to a chronically relapsing addict who understands fully that he or she is powerless (Step 1) but has excessive difficulty in dealing with resentments in the course of a 12-step recovery program (Steps 8 and 9) (33).

Cloninger (34) relates the 12 steps of AA to his 15-step psychobiological model of personality. Both of these provide a systemic basis for individual treatment planning and tailoring different treatment interventions based on the unique needs of each patient. Because the TCI-R dimensions correlate with the 12-steps of AA, it is easy to relate the TCI-R findings to the steps patients are doing in AA. For example, Step 1 in AA “We admitted we were powerless over alcohol alcohol—that our lives had become unmanageable” can correlate directly with the first subscale of Self-Directedness, that relates to taking responsibility and not blaming others.

Temperament and character also help to integrate the 12-step work on character development with the treatment of comorbid conditions with pharmacotherapy and other adjunctive therapies such as biofeedback. The physician and patient can work together in a healthy alliance to regulate and moderate extremes of temperament (anxiety proneness, anger or impulse proneness, and an excessive need for approval) in a variety of ways (i.e., medications, exercise, diet, recreational activities, and others). The tools provided through AA and the examination of personality via the TCI-R and collage promote the idea that it the patient is responsible for the choices he or she makes in life. The treating physician clarifies, encourages, and recommends a positive cycle of healing.

The TCI-R has an additional benefit of creating a common language for staff and patients. The subscales, such as “anticipatory worry” under the Temperament dimension of Harm Avoidance, can provide a means for patients to articulate this phenomenon, which allows them to gain understanding and insight from clinicians and peers. This common language phenomenon is already one of the assets of AA.

The TCI-R can assist in the patient's gaining an increased awareness of personality, and, in addition, repeating the TCI-R can inform the patient as to how his or her self-perceptions can change over time. With the handout shown in Appendix A, patients in the program are able to organize the information from their TCI-R results and integrate the findings in various ways in the treatment experience, including small group process and individual counseling.

USE OF MINDFULNESS AND MEDITATION

The TCI-R offers a profile of the spiritual dimension of a person through the Self-Transcendence character dimension. The measurement of spirituality as a function of personality is unique to this self-report and particularly relevant to addiction treatment in which spiritual growth is a goal in the patient's treatment. Self-Transcendence is a personality factor widely accepted as a paradigm for psychological growth, and, according to Cloninger (34), is developed in a more stepwise manner than the character dimensions of Self-Directedness and Cooperativeness. A number of studies have examined the role of spiritual growth in addiction recovery (35, 36). These studies have used various self-reports such as the Spiritual Well-Being Scale (37) and the Spirituality Self Rating Scale (36). The TCI-R includes personality variables, such as a measure of Self-Transcendence, which can facilitate or impede the recovery process. This measurement opens communication by the patient and the staff on the topic of spirituality.

Self-Transcendence in a more generalized framework refers to one's ability to have healed sufficiently from psychological distress to summon an aspect of conflict-free ego functioning that allows for factors such as creativity, wisdom, and spirituality. Cloninger, when referencing the Self-Transcendence scale of the TCI-R, advances a state of caution in evaluation of an individual's style of self-transcendence. While stating that self-transcendence involves a state of high evolution, Cloninger also cautions that high scores on the Self-Transcendence character scale of the TCI-R may indicate factors such as compromised interpersonal boundaries and inadequately formed self-structures. Most patients are encouraged to practice mindfulness and meditation, which can facilitate calming the mind and assist the patient in observing his or her thoughts, thereby enhancing the opportunity for subconscious thoughts to emerge. However, in those patients who score very high in Self-Transcendence, especially if they are low in Self-Directedness and Cooperativeness, meditation and mindfulness are initially deemphasized.

After the mind is steadied and the patient can confidently practice an observing-ego stance, he or she begins to see results in an increase in self-aware consciousness. The technique of contemplation involves a deeper level of self-aware consciousness and facilitates patient access to aspects of the unconscious mind. Simultaneous with this enhanced awareness, patients are instructed to experience a state of oneness with everything and to find some degree of refuge in this awareness. As patients practice these progressive techniques of calming the mind, enhancing self-aware consciousness, and practicing contemplation, the dynamic of self-transcendence can be built in a stepwise manner into their consciousness.

Learning how to be present in the moment can have significant benefit to addicts. This has been well demonstrated in a multitude of mental disorders including depression, anxiety, personality disorders, and addiction (38). Examining Self-Transcendence as a measurable personality variable (best represented by the self-forgetfulness subscale) has been helpful in guiding the treatment team to incorporate meditative practices in the treatment plans for patients enrolled in the professionals program.

The disease of addiction has a neurobiological and psychological underpinning that can be called “the addictive drive,” which is quiescent in recovery but remains dormant. That is why sober addicts are in “recovery” but never “recovered.” This addictive drive, however, can represent a unique opportunity. When this drive presents itself in recovery in its various forms, such as craving or feelings of deprivation, these symptoms of the disease can remind one of the need to continue and even intensify a meditative practice along with other recovery activities. Through sublimation, the addictive drive can be fuel for transcendence. The sober addict can achieve and maintain these higher states of consciousness and the improved relationships with self, others, and the higher power that emanates from them. Dr. Andrew Newberg determined that just 12 minutes of a focused meditation demonstrated positive changes in key areas of the brain, including the prefrontal cortex and anterior cingulate (39). These changes suggested improvements in memory, mood, and attention and a reduction in anxiety. In fact, imaging showed that these changes occurred over just an 8-week period. For the sober addict, this simple yet profound practice can reduce stress, reduce craving, improve mood, and even create a capacity for experiencing higher and ultimately profoundly rewarding states of consciousness. For the clinician, incorporating mindfulness in his or her practice can be highly beneficial for both therapist and patient.

OTHER TOOLS

Along with the use of the TCI-R, the treatment program provides the “Know Yourself” DVD series to patients as part of their education. This DVD series walks the patient through both a conceptual framework of what can bring satisfaction, as well as meditative experiences that reinforce these concepts (40). The series was developed using the essential content of the book by Cloninger, Feeling Good: The Science of Well Being (25). Concepts, summarized as Hope, Faith, and Love, are presented: Love is described as a sense of unity and connectedness with others, reinforced through working in the service of others and through acts of kindness. Hope recognizes the necessity of having a sense of meaning and purpose and having goals that one is willing to work hard to achieve. With Hope one is able to take responsibility and gain self-acceptance, thereby giving up the struggle with one's self and letting go with a degree of optimism. Faith “comes from listening to one's deepest intuitions about the fundamental nature of the world” (40). Patients watch the series weekly. Specific exercises are given to reinforce the concepts including how to self-observe and perform acts of kindness. There is a description of the TCI-R and how to access it, with a correlation between the three aspects described above and the three dimensions of character, Cooperativeness, Self-Directedness, and Self-Transcendence.

Other DVD's in the series examine the possible results of the TCI-R while exploring the levels of thought; initial perception, words and emotions, and actions and new emotions. It describes thought patterns that can lead to depression, anxiety and addiction. These levels of thought are correlated with the TCI-R Temperament configurations with examples on how this can shape initial perceptions. Three practices that bring well-being—working in the service of others, letting go, and growing in awareness—are discussed. In addition, meditative techniques to reduce anxiety, and alleviate loneliness and isolation are presented and a section on how to use one's intuition to gain a more defined outlook on life. This series along with an addiction-specific workbook approach to recovery constitutes a course on well-being within this treatment program that is completely compatible with the 12-step therapeutic community model described.

RESEARCH AND OUTCOMES

The treatment team at this program is now examining their patient population based on the test results of initial and repeated TCI-R to determine whether growth in character (as perceived by the patients through these self-reports) influences sobriety/abstinence and quality of life. A recent study of addicted women in a 4-week residential abstinence-based 12-step oriented treatment program demonstrated improvement in character dimension scores when the TCI-R was repeated after a 6-month interval (41). All three character dimensions increased for those women who completed treatment, especially Self-Directedness, for which low scores suggest personality disorders (28). This study suggests the potential for flexibility of personality disorders and adaptations in a substance-abusing population. The study also noted that higher Persistence and lower Novelty Seeking scores at baseline predicted higher completion rates. “Individuals who score high on Persistence tend to endorse being industrious and persevering” (42), which may contribute to improved abstinence and quality of life. The program is currently repeating administration of the TCI-R after the onset of treatment as follows: at end of treatment (average 8 weeks) and at 6 and 12 months. The goal is to determine the influence of temperament and character fluctuations on the abstinence rates and quality of life of the addicted professionals in the program.

WORKING WITH PSYCHIATRISTS

Incorporating the TCI-R and DVD series has allowed patients and staff to move beyond traditional modes of therapeutic constructs. Using the above concepts and the TCI-R as a common point of communication evolved into an expanded therapeutic experience for patient and therapist. Several consulting psychiatrists and clinicians who follow patients after discharge also have adopted this type of communication in which discussions go beyond simply focusing on specific psychopathology and medication management. Because some consulting psychiatrists are using the TCI-R and DVD series in their practice, there is enhanced continuity of care and a collaborative focus on well-being.

CONCLUSION

The TCI-R has expanded the realm of treatment approaches for patients treated in a program for addicted professionals. By focusing on personality and well-being, the program has been able to develop a more dynamic, person-centered approach to the addicted patient. The use of these elements has allowed the program to build on the existing strengths of the 12-step-oriented therapeutic community model in a way that enhances, not replaces, this successful model. This expansion has created a common language and emphasis that allows for outcome studies as well as enhanced communication between patients, staff, and consulting psychiatrists and clinicians. The expansion of the program's concept of addiction has reduced the stigma and recognized the complexity of disease processes, while facilitating a focus on understanding the emotional style and adaptive skills of the whole person. Last, it increases the engagement of patients in their treatment experience through their ability to visually and actively change personality traits that will enhance their recovery and feelings of satisfaction.

1 Geppert C, Bogenschutz MP, Miller WR: Development of a bibliography on religion, spirituality and addictions. Drug Alcohol Rev 2007; 26:389–395 Crossref, Google Scholar

2 Morse RM, Flavin DK: The definition of alcoholism. The Joint Committee of the National Council on Alcoholism and Drug Dependence and the American Society of Addiction Medicine to Study the Definition and Criteria for the Diagnosis of Alcoholism. JAMA 1992; 268:1012–1014 Crossref, Google Scholar

3 Carnes P: Addiction interaction disorder, in Handbook of Addictive Disorders: a Practical Guide to Diagnosis and Treatment. Edited by Coombs RH. Hoboken, NJ, John Wiley & Sons, 2004, pp xvi, 584 Google Scholar

4 Barry D, Clarke M, Petry NM: Obesity and its relationship to addictions: is overeating a form of addictive behavior? Am J Addict 2009; 18:439–451 Crossref, Google Scholar

5 Fladung AK, Gron G, Grammer K, Herrnberger B, Schilly E, Grasteit S, Wolf RC, Walter RC, von Wietersheim: A neural signature of anorexia nervosa in the ventral striatal reward system. Am J Psychiatry 2010; 167:206–212 Crossref, Google Scholar

6 Kalivas PW, Volkow ND: The neural basis of addiction: a pathology of motivation and choice. Am J Psychiatry 2005; 162:1403–1413 Crossref, Google Scholar

7 Hughes C: Substance Abuse and the Nation's Number One Health Problem. Princeton, NJ, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, 2001 Google Scholar

8 Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA): Most who need addiction treatment don't receive it. American Society of Medicine Newsletter.

9 McElrath D: The Minnesota model. J Psychoactive Drugs 1997; 29:141–144 Crossref, Google Scholar

10 Khantzian EJ, Mack JE: How AA works and why it's important for clinicians to understand. J Subst Abuse Treat 1994; 11:77–92 Crossref, Google Scholar

11 Project Match Research Group: Matching alcoholism treatments to client heterogeneity: Project Match posttreatment drinking outcomes. J Addict Studies Alcohol 1997; 58:7–29 Crossref, Google Scholar

12 Skodol AE, Oldham JM, Gallaher PE: Axis II comorbidity of substance use disorders among patients referred for treatment of personality disorders. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:733–738 Google Scholar

13 DeJong CA, van den Brink W, Harteveld FM, van der Wielen EG: Personality disorders in alcoholics and drug addicts. Compr Psychiatry 1993; 34:87–94 Crossref, Google Scholar

14 Verheul R, van den Bosch L, Ball S. Substance abuse, In Textbook of Personality Disorders. Edited by Oldham J, Skodol A, Bender D. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc., 2005, pp 463–475 Google Scholar

15 Zimmerman M, Coryell W: DSM-III personality disorder diagnoses in a nonpatient sample. Demographic correlates and comorbidity. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1989; 46:682–689 Crossref, Google Scholar

16 Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Dubo ED, Sickel AE, Trikha A, Levin A, Reynolds V: Axis I comorbidity of borderline personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:1733–1739 Crossref, Google Scholar

17 Heinz A, Siessmeier T, Wrase J, Buchholz HG, Grunder G, Kumakura Y, Cumming P, Schreckenberger M, Smolka MN, Rösch F, Mann K, Bartenstein P: Correlation of alcohol craving with striatal dopamine synthesis capacity and D2/3 receptor availability: a combined [18F]DOPA and [18F]DMFP PET study in detoxified alcoholic patients. Am J Psychiatry 2005; 162:1515–1520 Crossref, Google Scholar

18 Cloninger CR, Sigvardsson S, Bohman M: Childhood personality predicts alcohol abuse in young adults. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 1988; 12:494–505 Crossref, Google Scholar

19 Krampe H, Wagner T, Stawicki S, Bartels C, Aust C, Kroener-Herwig B, Kuefner H, Ehrenreich H: Personality disorder and chronicity of addiction as independent outcome predictors in alcoholism treatment. Psychiatr Serv 2006; 57:708–712 Crossref, Google Scholar

20 Nathan PE: The addictive personality is the behavior of the addict. J Consult Clin Psychol 1988; 56:183–188 Crossref, Google Scholar

21 Dagher A, Robbins TW: Personality, addiction, dopamine: insights from Parkinson's disease. Neuron 2009; 61:502–510 Crossref, Google Scholar

22 Insel TR: Is social attachment an addictive disorder? Physiol Behav 2003; 79:351–357 Crossref, Google Scholar

23 Stanley B, Siever LJ: The interpersonal dimension of borderline personality disorder: toward a neuropeptide model. Am J Psychiatry 2010; 167:24–39 Crossref, Google Scholar

24 Jones ER: Crossing the field's quality chasm. Behav Healthc 2006; 26:23–24 Google Scholar

25 Cloninger CR: Feeling Good: The Science of Well-Being. New York, Oxford University Press, 2004 Google Scholar

26 Cloninger CR, Svrakic DM: Integrative psychobiological approach to psychiatric assessment and treatment. Psychiatry 1997; 60:120–141 Crossref, Google Scholar

27 Cloninger CR, Svrakic DM, Przybeck TR: A psychobiological model of temperament and character. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1993; 50:975–990 Crossref, Google Scholar

28 Svrakic DM, Draganic S, Hill K, Bayon C, Przybeck TR, Cloninger CR: Temperament, character, and personality disorders: etiologic, diagnostic, treatment issues. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2002; 106:189–195 Crossref, Google Scholar

29 Mulder RT, Joyce PR, Sellman JD, Sullivan PF, Cloninger CR: Towards an understanding of defense style in terms of temperament and character. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1996; 93:99–104 Crossref, Google Scholar

30 Arnau MM, Mondon S, Santacreu JJ: Using the temperament and character inventory (TCI) to predict outcome after inpatient detoxification during 100 days of outpatient treatment. Alcohol Alcohol 2008; 43:583–588 Crossref, Google Scholar

31 Kaskutas LA, Subbaraman MS, Witbrodt J, Zemore SE: Effectiveness of making Alcoholics Anonymous easier: a group format 12-step facilitation approach. J Subst Abuse Treat 2009; 37:228–239 Crossref, Google Scholar

32 Alcoholics Anonymous: Twelve Steps and Twelve Traditions. New York, World Services, Inc., 1953, p 73 Google Scholar

33 Angres DH, Nielsen AK: The role of the TCI-R (Temperament Character Inventory) in individualized treatment planning in a population of addicted professionals. J Addict Dis. 2007; 26(suppl 1):51–64 Google Scholar

34 Cloninger C: A 15 step model of personality development: assessment and treatment implications for alcoholism, in The Long and the Short of Treatment for Alcohol and Drug Disorders. Edited by Sellman JD, Robinson GM, McCormick R, Dore GM. Christchurch, NZ, Department of Psychological Medicine, Christchurch School of Medicine, 1997, pp 45–76 Google Scholar

35 Galanter M: Spirituality and recovery in 12-step programs: an empirical model. J Subst Abuse Treat 2007; 33:265–272 Crossref, Google Scholar

36 Galanter M, Dermatis H, Bunt G, Williams C, Trujillo M, Steinke P: Assessment of spirituality and its relevance to addiction treatment. J Subst Abuse Treat 2007; 33:257–264 Crossref, Google Scholar

37 Piderman KM, Schneekloth TD, Pankratz VS, Maloney SD, Altchuler SI: Spirituality in alcoholics during treatment. Am J Addict 2007; 16:232–237 Crossref, Google Scholar

38 McGee M: Meditation and psychiatry. Psychiatry 2008; 5:28–41 Google Scholar

39 Newberg A, Waldman M: How God Changes Your Brain: Breakthrough Findings from a Leading Neuroscientist. New York, Ballantine Books, 2009 Google Scholar

40 Anthropedia Foundation: The Know Yourself DVD Series. http://www.anthropediafoundation.org/resources_knowyourself Google Scholar

41 Borman PD, Zilberman ML, Tavares H, Suris AM, el-Guebaly N, Foster B: Personality changes in women recovering from substance-related dependence. J Addict Dis. 2006; 25:59–66 Crossref, Google Scholar

42 Gusnard DA, Ollinger JM, Shulman GL, Cloninger CR, Price JL, Van Essen DC, Raichle RA. Persistence and brain circuitry. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2003; 100:3479–3484 Crossref, Google Scholar