Clinical Management Guidelines for Obstetrician-Gynecologists Use of Psychiatric Medications During Pregnancy and Lactation

Abstract

It is estimated that more than 500,000 pregnancies in the United States each year involve women who have psychiatric illnesses that either predate or emerge during pregnancy, and an estimated one third of all pregnant women are exposed to a psychotropic medication at some point during pregnancy (1). The use of psychotropic medications is a cause of concern for physicians and their patients because of the potential teratogenic risk, the risk of perinatal syndromes or neonatal toxicity, and the risk for abnormal postnatal behavioral development. With the limited information available on the risks of the psychotropic medications, clinical management must incorporate an appraisal of the clinical consequences of offspring exposure, the potential effect of untreated maternal psychiatric illness, and the available alternative therapies. The purpose of this document is to present current evidence on the risks and benefits of treatment for certain psychiatric illnesses during pregnancy.

(Reprinted with permission from Obstetrics & Gynecology 2008; 111:1001–1020)

BACKGROUND

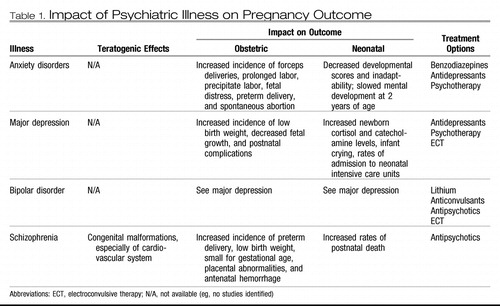

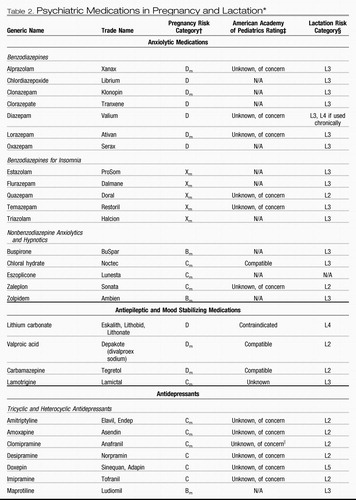

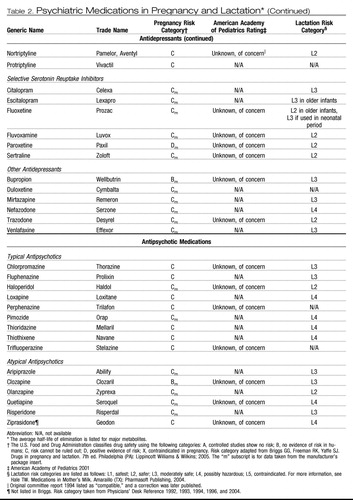

Advising a pregnant or breastfeeding woman to discontinue medication exchanges the fetal or neonatal risks of medication exposure for the risks of untreated maternal illness. Maternal psychiatric illness, if inadequately treated or untreated, may result in poor compliance with prenatal care, inadequate nutrition, exposure to additional medication or herbal remedies, increased alcohol and tobacco use, deficits in mother-infant bonding, and disruptions within the family environment (see Table 1). All psychotropic medications studied to date cross the placenta (1), are present in amniotic fluid (2), and can enter human breast milk (3). For known teratogens, knowledge of gestational age is helpful in the decision about drug therapy because the major risk of teratogenesis is during embryogenesis (ie, during the third through the eighth week of gestation). The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has provided a system for categorizing individual medications (see Table 2), although this system has considerable limitations. Categories of risk for neonates from drugs used while breastfeeding also are shown in Table 2. Electronic resources for information related to the fetal and neonatal effects of psychotropic drug therapy in pregnancy and with breastfeeding include Reprotox (www.reprotox.org) and TERIS (http://depts.washington.edu/terisweb). Providing women with patient resources for online information that are well referenced is a reasonable option.

|

Table 1. Impact of Psychiatric Illness on Pregnancy Outcome

|

|

Table 2. Psychiatric Medications in Pregnancy and Lactation*

GENERAL TREATMENT CONCEPTS

Optimally, shared decision making among obstetric and mental health clinicians and the patient should occur before pregnancy. Whenever possible, multidisciplinary management involving the obstetrician, mental health clinician, primary health care provider, and pediatrician is recommended to facilitate care.

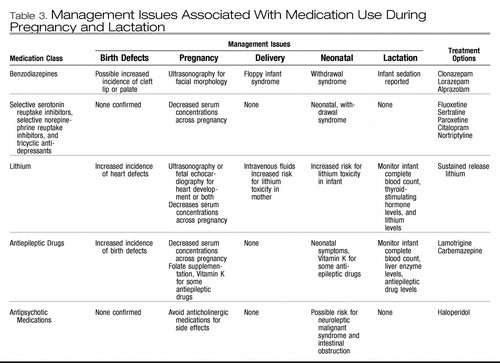

A single medication at a higher dose is favored over multiple medications for treatment of psychiatric illness during pregnancy. Changing medications increases the exposure to the offspring. The selection of medication to minimize the risk of illness should be based on history of efficacy, prior exposure during pregnancy, and available reproductive safety information (see Table 3). Medications with fewer metabolites, higher protein binding (decreases placental passage), and fewer interactions with other medications are preferred.

|

Table 3. Management Issues Associated With Medication Use During Pregnancy and Lactation

MAJOR DEPRESSION

Prevalence rates for depression are estimated at 17% for adults in the United States (4); women twice as often as men experience depression (5). The highest rates for depression occur in women between the ages of 25 years and 44 years (6). Symptoms include depressed or irritable mood, anhedonia, weight loss or gain, appetite and sleep changes, loss of energy, feelings of excessive guilt or worthlessness, psychomotor agitation or retardation and, in more severe cases, suicidal ideation (7). Approximately 10–16% of pregnant women fulfill diagnostic criteria for depression, and up to 70% of pregnant women report symptoms of depression (6, 8–10). Many symptoms of depression overlap with the symptoms of pregnancy and often are overlooked (6, 11). Of women taking antidepressants at conception, more than 60% experienced symptoms of depression during the pregnancy (12). In a study of pregnant women taking antidepressants before conception, a 68% relapse of depression was documented in those who discontinued medications during pregnancy (13) compared with only a 25% relapse in those who continued antidepressant medications.

Postpartum depression is classified as a major episode of depression that occurs within the first 4 weeks postpartum (7) or within the first 6 weeks postpartum (14). Many women in whom postpartum depression was diagnosed reported having symptoms of depression during pregnancy (9, 15–17). These symptoms may be difficult to differentiate from normal postpartum adaptation. Survey tools (eg, Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale, Beck Depression Inventory, and the Postpartum Depression Screening Scale), are widely used to identify depression during the perinatal period (18). The detection rate is in the range of 68–100% (better for severe depression) with specificities in the range of 78–96% (19).

Untreated maternal depression is associated with an increase in adverse pregnancy outcomes, including premature birth, low birthweight infants, fetal growth restriction, and postnatal complications. This association is stronger when depression occurs in the late second to early third trimester (20). Newborns of women with untreated depression during pregnancy cry more and are more difficult to console (20–22). Maternal depression also is associated with increased life stress, decreased social support, poor maternal weight gain, smoking, and alcohol and drug use (23), all of which can adversely affect infant outcome (24–26). Later in life, children of untreated depressed mothers are more prone to suicidal behavior, conduct problems, and emotional instability and more often require psychiatric care (27, 28).

BIPOLAR DISORDER

Bipolar disorder, historically called manic-depressive disorder, affects between 3.9% and 6.4% of Americans and affects men and women equally (4, 29–31). It commonly is characterized by distinct periods of abnormally and persistently elevated, expansive, or irritable mood and separate distinct periods of depressed mood or anhedonia (7). Women are more likely than men to experience depressive episodes of bipolar disorder (32), rapid cycling (33), and mixed episodes (34, 35). Typical onset of bipolar disorder for women is in the teens or early twenties.

Rates of postpartum relapse range from 32% (36) to 67% (37). In one study, it was reported that pregnancy had a protective effect for women with bipolar disorder (38), but the participants may have had milder illness. Perinatal episodes of bipolar disorder tend to be depressive (37, 39) and, when experienced with one pregnancy, are more likely to recur with subsequent pregnancies (37). There also is an increased risk of postpartum psychosis as high as 46% (40, 41).

ANXIETY DISORDERS

Anxiety disorders include panic disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), social anxiety disorder, and specific phobias. Collectively, anxiety disorders are the most commonly occurring psychiatric disorders, with a prevalence of 18.1% among adults 18 years and older in the United States (42). Panic disorder, GAD, PTSD, agoraphobia, and specific phobias are two times more likely to be diagnosed in women than men. Anxiety and stress during pregnancy are documented as factors associated with poor obstetric outcomes, including spontaneous abortions (43), preterm delivery (44, 45), and delivery complications (46), such as prolonged labor, precipitate labor, clinical fetal distress, and forceps deliveries (47). A direct causal relationship has not been established.

Panic disorder is characterized by recurrent panic attacks that arise spontaneously in situations that are not expected to cause anxiety. Most investigators agree that women are at greatest risk for exacerbation of panic disorder during the postpartum period (48, 49). In a recent study PTSD was reported to be the third most common psychiatric diagnosis among economically disadvantaged pregnant women, with a prevalence of 7.7% (50). Women with PTSD were significantly more likely to have a comorbid condition, principally major depression or GAD. Many reports have documented traumatic obstetric experiences (eg, emergency delivery, miscarriage, and fetal demise) as precipitants to PTSD-related symptomatology. The incidence of OCD during pregnancy is unknown. Despite limited formal investigation, most clinicians and researchers agree that pregnancy seems to be a potential trigger of OCD symptom onset, with 39% of the women in a specialized OCD clinic experiencing symptom onset during pregnancy (51). It generally is accepted that OCD worsens during the postpartum period.

SCHIZOPHRENIA-SPECTRUM DISORDERS

Schizophrenia is a severe and persistent mental illness characterized by psychotic symptoms, negative symptoms, such as flat affect and lack of volition, and significant occupational and social dysfunction (7). Schizophrenia occurs in approximately 1–2% of women, with the most common age of onset during the childbearing years (52).

A variety of adverse pregnancy outcomes in women with schizophrenia have been reported, including preterm delivery, low birth weight infants, small for gestational age fetuses (53, 54), placental abnormalities and antenatal hemorrhage, increased rates of congenital malformations, especially of the cardiovascular system (55), and a higher incidence of postnatal death (53). However, in one study it was found that schizophrenic women were not at higher risk for specific obstetric complications but were at greater risk of requiring interventions during delivery, including labor induction and assisted or cesarean delivery (56). If left untreated during pregnancy, schizophrenia-spectrum disorders can have devastating effects on both mother and child, with rare reports of maternal self-mutilation (57, 58), denial of pregnancy resulting in refusal of prenatal care (59), and infanticide (60, 61).

CLINICAL CONSIDERATIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

▶ What is the evidence regarding the safety and efficacy of treatment for depression during pregnancy?

Most data related to antidepressants in pregnancy are derived from the use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) (fluoxetine, sertraline, citalopram, and paroxetine). Overall, there is limited evidence of teratogenic effects from the use of antidepressants in pregnancy or adverse effects from exposure during breastfeeding (62–64). There are two reports from GlaxoSmithKline based on a Swedish national registry and a U.S. insurance claims database that have raised concerns about a 1.5–2-fold increased risk of congenital cardiac malformations (atrial and ventricular septal defects) associated with first-trimester paroxetine exposure (www.gskus.com/news/paroxetine/paxil_letter_e3.pdf). The manufacturer subsequently changed paroxetine's pregnancy FDA category from C to D (www.fda.gov/cder/drug/advisory/paroxetine200512.htm).

More recently, the teratogenic effect of SSRI use during the first trimester of pregnancy was examined in two large case-control studies from multisite surveillance programs (65, 66). In the National Birth Defects Prevention Study, no significant associations were found between SSRI use overall and congenital heart defects (66). However, an association was found between SSRI use (particularly paroxetine) during early pregnancy and anencephaly, craniosynostosis, and omphalocele. Importantly, these risks were found only after more than 40 statistical tests were performed. Even if findings were not the result of chance, the absolute risks associated with SSRI use identified in this study were small. For example, a twofold to threefold increase in birth defects would occur for omphalocele (1 in 5,000 births), craniosynostosis (1 in 1,800 births) and anencephaly (1 in 1,000 births). In contrast, in the Slone Epidemiology Center Birth Defects Study no increased risk of craniosynostosis, omphalocele, or heart defects associated with SSRI use overall during early pregnancy was found (65). An association was seen between paroxetine and right ventricular outflow defects. Additionally, sertraline use was associated with omphalocele and atrial and ventricular septum defects. A limitation of this study is that the authors conducted 42 comparisons in their analyses for their main hypotheses. Both of these case-control studies were limited by the small number of exposed infants for each individual malformation. The current data on SSRI exposure during early pregnancy provide conflicting data on the risk for both overall and specific malformations. Some investigators have found a small increased risk of cardiac defects, specifically with paroxetine exposure. The absolute risk is small and generally not greater than two per 1,000 births; hence, these agents are not considered major teratogens.

Exposure to SSRIs late in pregnancy has been associated with transient neonatal complications, including jitteriness, mild respiratory distress, transient tachypnea of the newborn, weak cry, poor tone, and neonatal intensive care unit admission (67–71). A more recent FDA public health advisory highlighted concerns about the risk of an unconfirmed association of newborn persistent pulmonary hypertension with SSRI use (72) (www.fda.gov/cder/drug/advisory/SSRI_PPHN200607.htm).

The potential risk of SSRI use in pregnancy must be considered in the context of the risk of relapse of depression if treatment is discontinued. Factors associated with relapse during pregnancy include a long history of depressive illness (more than 5 years) and a history of recurrent relapses (more than four episodes) (13). Therefore, treatment with all SSRIs or selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors or both during pregnancy should be individualized. At this time, paroxetine use in pregnant women and women planning pregnancy should be avoided, if possible. Fetal echocardiography should be considered for women exposed to paroxetine in early pregnancy. Because abrupt discontinuation of paroxetine has been associated with withdrawal symptoms, discontinuation of this agent should occur according to the product's prescribing information.

Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) have been available in the United States since 1963 and were widely used by women during pregnancy and lactation before the introduction of SSRIs. Results from initial studies, which suggested that TCA exposure might be associated with limb anomalies (73–75), have not been confirmed with subsequent studies (76, 77). Neonatal neurobehavioral effects from fetal exposure have not been reported (78).

Acute effects associated with TCA exposure include case reports of fetal tachycardia (79), neonatal symptoms such as tachypnea, tachycardia, cyanosis, irritability, hypertonia, clonus, and spasm (72–82), and transient withdrawal symptoms (83). In more recent studies, a significant link between prenatal exposure to TCAs and perinatal problems has not been documented (64, 84–86).

Atypical antidepressants are non-SSRI and non-TCA antidepressants that work by distinct pharmacodynamic mechanisms. The atypical antidepressants include bupropion, duloxetine, mirtazapine, nefazodone, and venlafaxine. The limited data of fetal exposure to these antidepressants (70, 85–89), do not suggest an increased risk of fetal anomalies or adverse pregnancy events. In the one published study of bupropion exposure in 136 patients, a significantly increased risk of spontaneous abortion, but not an increased risk of major malformations, was identified (90). In contrast, the bupropion registry maintained at GlaxoSmithKline has not identified any increased risk of spontaneous abortion, although these data have not undergone peer review.

Antidepressant medication is the mainstay of treatment for depression, although considerable data show that structured psychotherapy, such as interpersonal psychotherapy or cognitive behavioral therapy, are effective treatments for mild to moderate depression and are beneficial adjuncts to medication. In addition, electroconvulsive therapy is an effective treatment for major depression and is safe to use during pregnancy (91, 92).

▶ What is the evidence regarding the safety and efficacy of lithium for the treatment of bipolar disorders during pregnancy?

Use of lithium in pregnancy may be associated with a small increase in congenital cardiac malformations. The initial retrospective data suggested that fetal exposure to lithium was associated with a 400-fold increase in congenital heart disease, particularly Ebstein's anomaly (93, 94). A subsequent meta-analysis of the available data calculated the risk ratio for cardiac malformations to be 1.2–7.7 and the risk ratio for overall congenital malformations to be 1.5–3 (95). In more recent small studies, limited in their statistical power, the magnitude of early estimates of teratogenic potential of lithium could not be confirmed (96–98).

Fetal exposure to lithium later in gestation has been associated with fetal and neonatal cardiac arrhythmias (99), hypoglycemia, nephrogenic diabetes insipidus (100), polyhydramnios, reversible changes in thyroid function (101), premature delivery, and floppy infant syndrome similar to that seen with benzodiazepine exposure (102). Symptoms of neonatal lithium toxicity include flaccidity, lethargy, and poor suck reflexes, which may persist for more than 7 days (103). Neurobehavioral sequelae were not documented in a 5-year follow-up of 60 school-aged children exposed to lithium during gestation (104).

The physiologic alterations of pregnancy may affect the absorption, distribution, metabolism and elimination of lithium, and close monitoring of lithium levels during pregnancy and postpartum is recommended. The decision to discontinue lithium therapy in pregnancy because of fetal risks should be balanced against the maternal risks of exacerbation of illness. In a recent study, it was reported that abrupt discontinuation of lithium was associated with a high rate of bipolar relapse among pregnant women (39). The following treatment guidelines have been suggested for women with bipolar illness who are treated with lithium and plan to conceive: 1) in women who experience mild and infrequent episodes of illness, treatment with lithium should be gradually tapered before conception; 2) in women who have more severe episodes but are only at moderate risk for relapse in the short term, treatment with lithium should be tapered before conception but reinstituted after organogenesis; 3) in women who have especially severe and frequent episodes of illness, treatment with lithium should be continued throughout gestation and the patient counseled regarding reproductive risks (95). Fetal assessment with fetal echocardiography should be considered in pregnant women exposed to lithium in the first trimester. For women in whom an unplanned conception occurs while receiving lithium therapy, the decision to continue or discontinue the use of lithium should be in part based on disease severity, course of the patient's illness, and the point of gestation at the time of exposure.

▶ What is the evidence regarding the safety and efficacy of the antiepileptic drugs valproate and carbamazepine for the treatment of bipolar disorders during pregnancy?

Several anticonvulsants, including valproate, carbamazepine, and lamotrigine, currently are used in the treatment of bipolar disorder. Data regarding fetal effects of these drugs are derived primarily from studies of women with seizures. Whether the underlying pathology of epilepsy contributes to the teratogenic effect on the fetus is unclear. Epilepsy may not contribute to the teratogenic effects of antiepileptic drugs based on the results of a recent study that demonstrated similar rates of anomalies between infants of women without epilepsy and infants of women with epilepsy but who had not taken antiepileptic drugs during pregnancy (105).

Prenatal exposure to valproate is associated with a 1–3.8% risk of neural tube defects, with a corresponding dose-response relationship (106–113). Other congenital malformations associated with valproate use include craniofacial anomalies (114), limb abnormalities (115), and cardiovascular anomalies (116–118). A “fetal valproate syndrome” has been described with features of fetal growth restriction, facial dysmorphology, and limb and heart defects (119–121). Varying degrees of cognitive impairment, including mental development delay (122), autism (123–126), and Asperger's syndrome (124), have been reported with fetal valproate syndrome (124, 127, 128). Acute neonatal risks include hepatotoxicity (129), coagulopathies (130), neonatal hypoglycemia (131), and withdrawal symptoms (132).

Carbamazepine exposure in pregnancy is associated with a fetal carbamazepine syndrome manifest by facial dysmorphism and fingernail hypoplasia (124, 133–136). It is unclear whether carbamazepine use increases the risk of fetal neural tube defects or developmental delay (124, 127, 133–139). Fetal exposure to lamotrigine has not been documented to increase the risk of major fetal anomalies (140–145), although there may be an increased risk of midline facial clefts (0.89% of 564 exposures) as reported by one pregnancy registry (143), possibly related to higher daily maternal doses (greater than 200 mg/day) (145). The reproductive safety of lamotrigine appears to compare favorably with alternative treatments, but lacking are studies of the effectiveness of this antiepileptic drug as a mood stabilizer in pregnancy.

In managing bipolar disorders, the use of valproate and carbamazepine are superior to that of lithium for patients who experience mixed episodes or rapid cycling but exhibit limited efficacy in the treatment of bipolar depression. In contrast, lamotrigine is efficacious in the prevention of the depressed phase of illness (146, 147). Lamotrigine is a potential maintenance therapy option for pregnant women with bipolar disorder because of its protective effects against bipolar depression, general tolerability, and growing reproductive safety profile relative to alternative mood stabilizers. Because both valproate and carbamazepine are associated with adverse effects when used during pregnancy, their use, if possible should be avoided especially during the first trimester. The effectiveness of folate supplementation in the prevention of drug-associated neural tube defects has not been documented; however, folate supplementation of 4 mg/day should be offered preconceptionally and for the first trimester of pregnancy. Prenatal surveillance for congenital anomalies by maternal serum alpha-fetoprotein level testing, fetal echocardiography, or a detailed ultrasound examination of the fetal anatomy or a combination of these procedures should be considered. Whether the use of antiepileptic drugs such as carbamazepine increase the risk of neonatal hemorrhage and whether maternal vitamin K supplementation is effective remains unclear (148).

▶ What is the evidence regarding the safety and efficacy of treatment for anxiety disorders during pregnancy?

Use of benzodiazepines does not appear to carry a significant risk of somatic teratogenesis. In early studies of in utero exposure to diazepam, a benzodiazepine, an increased risk of oral clefts was reported (149–151). In a subsequent meta-analysis, it was demonstrated that prenatal benzodiazepine exposure increased the risk of oral cleft, although the absolute risk increased by 0.01%, from 6 in 10,000 to 7 in 10,000 (76). In a recent case-control study of 22,865 infants with congenital anomalies and 38,151 infants without congenital anomalies, an association of congenital anomalies, including oral clefts with exposure to five different benzodiazepines, was not found (152). Similar findings were documented in a case-control study of clonazepam (153). If discontinuation of benzodiazepine use is considered during pregnancy, benzodiazepines should not be abruptly withdrawn.

The data regarding neonatal toxicity and withdrawal syndromes are well documented, and neonates should be observed closely in the postpartum period. Floppy infant syndrome, characterized by hypothermia, lethargy, poor respiratory effort, and feeding difficulties, is associated with maternal use of benzodiazepines shortly before delivery (154–162). Neonatal withdrawal syndromes, characterized by restlessness, hypertonia, hyperreflexia, tremulousness, apnea, diarrhea, and vomiting, have been described in infants whose mothers were taking alprazolam (163), chlordiazepoxide (164–166), or diazepam (167, 168). These symptoms have been reported to persist for as long as 3 months postpartum (81).

The long-term neurobehavioral impact of prenatal benzodiazepine exposure is unclear. The existence of a “benzodiazepine-exposure syndrome,” including growth restriction, dysmorphism, and both mental and psychomotor retardation, in infants exposed prenatally to benzodiazepines is disputed (169–171). In one study, no differences in the incidence of behavioral abnormalities at age 8 months or IQ scores at age 4 years were found among children exposed to chlordiazepoxide during gestation (172).

▶ What is the evidence regarding the safety and efficacy of treatment for schizophrenia during pregnancy?

The atypical antipsychotics (eg, clozapine, olanzapine, quetiapine, risperidone, ziprasidone, and aripiprazole) have replaced the typical agents as first-line medications for psychotic disorders (Table 2). The atypical antipsychotics generally are better tolerated and possibly are more effective in managing the negative symptoms of schizophrenia. They also are used increasingly for bipolar disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and treatment-resistant depression. The reproductive safety data regarding the use of atypical antipsychotics remains extremely limited. In a prospective comparative study of pregnancy outcomes between groups exposed and unexposed to atypical antipsychotics, outcomes of 151 pregnancies with exposure to olanzapine, risperidone, quetiapine, and clozapine demonstrated a higher rate of low birth weight (10% in the exposed versus 2% in the nonexposed group) and therapeutic abortions (173).

The typical antipsychotic drugs have a larger reproductive safety profile and include haloperidol, thioridazine, fluphenazine, perphenazine, chlorpromazine, and trifluoperazine. No significant teratogenic effect has been documented with chlorpromazine, haloperidol, and perphenazine (174–176). In a study of 100 women treated with haloperidol (mean dose of 1.2 mg/day) for hyperemesis gravidarum, no differences in gestational duration, fetal viability, or birth weight were noted (177). In a large prospective study encompassing approximately 20,000 women treated primarily with phenothiazines for emesis (178), investigators found no significant association with neonatal survival rates or severe anomalies. Similar results have been obtained in several retrospective studies of women treated with trifluoperazine for repeated abortions and emesis (179, 180). In contrast, other investigators reported a significant association of major anomalies with prenatal exposure to phenothiazines with an aliphatic side chain but not with piperazine or piperidine class agents (181). Reanalysis of previously reported data obtained also identified a significant risk of malformations associated with phenothiazine exposure in weeks 4–10 of gestation (182). In clinical neurobehavioral outcome studies encompassing 203 children exposed to typical antipsychotics during gestation, no considerable differences have been detected in IQ scores at 4 years of age (183, 184), although relatively low antipsychotic doses were used by many women in these studies.

Fetal and neonatal toxicity reported with exposure to the typical antipsychotics includes neuroleptic malignant syndrome (185), dyskinesia (186), extrapyramidal side effects manifested by heightened muscle tone and increased rooting and tendon reflexes persisting for several months (187), neonatal jaundice (188), and postnatal intestinal obstruction (189).

Fetuses and infants also may be exposed to drugs used to manage the extrapyramidal side effects (eg, diphenhydramine, benztropine, and amantadine). In a case-control study, oral clefts were associated with a significantly higher rate of prenatal exposure to diphenhydramine than controls (149). In contrast, in several other studies diphenhydramine use has not been found to be a significant risk factor for fetal malformations (190, 191). Clinical studies of the teratogenic potential of benztropine and amantadine use are lacking.

In summary, typical antipsychotics have been widely used for more than 40 years, and the available data suggest the risks of use of these agents are minimal with respect to teratogenic or toxic effects on the fetus. In particular, use of piperazine phenothiazines (eg, trifluoperazine and perphenazine) may have especially limited teratogenic potential (181). Doses of typical antipsychotics during the peripartum should be kept to a minimum to limit the necessity of utilizing medications to manage extrapyramidal side effects. There is likewise little evidence to suggest that the currently available atypical antipsychotics are associated with elevated risks for neonatal toxicity or somatic teratogenesis. No long-term neurobehavioral studies of exposed children have yet been conducted. Therefore, the routine use of atypical antipsychotics during pregnancy and lactation cannot be recommended. In a woman who is taking an atypical antipsychotic and inadvertently conceives, a comprehensive risk-benefit assessment may indicate that continuing therapy with the atypical antipsychotic (to which the fetus has already been exposed) during gestation is preferable to switching to therapy with a typical antipsychotic (to which the fetus has not yet been exposed).

▶ What is the risk of using psychiatric drugs while breastfeeding?

Breastfeeding has clear benefits for both mother and infant and, in making the decision to recommend breast-feeding, these benefits should be weighed against the risks to the neonate of medication exposure while breast-feeding (Table 2). Most medications are transferred through breast milk, although most are found at very low levels and likely are not clinically relevant for the neonate. For women who breastfeed, measuring serum levels in the neonate is not recommended. Most clinical laboratory tests lack the sensitivity to detect and measure the low levels present. However, breastfeeding should be stopped immediately if a nursing infant develops abnormal symptoms most likely associated with exposure to the medication. Evaluation of the literature on drug levels in breast milk can facilitate the decision to breastfeed (192).

In the treatment of depression, published reports regarding SSRI use and lactation now consist of 173 mother-infant nursing pairs with exposure to sertraline, fluoxetine, paroxetine, fluvoxamine, and citalopram (193, 194–215). In results from studies, it has been shown that, quantitatively, medication exposure during lactation is considerably lower than transplacental exposure to these same SSRIs during gestation (193, 201, 208, 216). Generally, very low levels of SSRIs are detected in breast milk. Only a few isolated cases of adverse effects have been reported, although infant follow-up data are limited. The package insert for citalopram does report a case of an infant who experienced a transient apneic episode. Long-term neurobehavioral studies of infants exposed to SSRI antidepressants during lactation have not been conducted.

The TCAs also have been widely used during lactation. The only adverse event reported to date is respiratory depression in a nursing infant exposed to doxepin, which led to the conclusion that doxepin use should be avoided but that most TCAs are safe for use during breastfeeding (217). Data regarding the use of atypical antidepressants during lactation are limited to the use of venlafaxine (218) and bupropion (219, 220).

The existing data regarding lithium use and lactation encompass 10 mother-infant nursing dyads (103, 221–225). Adverse events, including lethargy, hypotonia, hypothermia, cyanosis, and electrocardiogram changes, were reported in two of the children in these studies (103, 223). The American Academy of Pediatrics consequently discourages the use of lithium during lactation (226). Because dehydration can increase the vulnerability to lithium toxicity, the hydration status of nursing infants of mothers taking lithium should be carefully monitored (102). There are no available reports regarding the long-term neurobehavioral sequelae of lithium exposure during lactation.

Only one adverse event, an infant with thrombocytopenia and anemia (227), has been reported in studies regarding valproate use and lactation, which includes 41 mother-infant nursing dyads (227–235). Studies of the neurobehavioral impact of valproate exposure during lactation have not been conducted. The American Academy of Pediatrics and the World Health Organization (WHO) Working Group on Drugs and Human Lactation have concluded that use of valproate is compatible with breast-feeding (226, 236). Reported adverse effects of carbamazepine in breast milk include transient cholestatic hepatitis (237, 238) and hyperbilirubinemia (239). The WHO Working Group on Drugs and Human Lactation has concluded that use of carbamazepine with breast-feeding is “probably safe” (236).

In the management of anxiety disorders, benzodiazepine use exhibits lower milk/plasma ratios than other classes of psychotropics (240, 241). Some investigators concluded that benzodiazepine use at relatively low doses does not present a contraindication to nursing (242). However, infants with an impaired capacity to metabolize benzodiazepines may exhibit sedation and poor feeding even with low maternal doses (243).

Of typical antipsychotic medications, chlorpromazine has been studied in seven breastfeeding infants, none of whom exhibited developmental deficits at 16-month and 5-year follow-up evaluations (244). However, three breastfeeding infants in another study, whose mothers were prescribed both chlorpromazine and haloperidol, exhibited evidence of developmental delay at 12–18 months of age (245).

RESOURCES

American Academy of Pediatrics

Web: www.aap.org

American Psychiatric Association

Web: www.psych.org

National Institutes of Health

Daily medication:

http://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/about.cfm

Lactation medication:

toxnet.nlm.nih.gov/cgi-bin/sis/htmlgen?LACT

SUMMARY OF RECOMMENDATIONS AND CONCLUSIONS

The following recommendations and conclusions are based on good and consistent scientific evidence (Level A):

▶ Lithium exposure in pregnancy may be associated with a small increase in congenital cardiac malformations, with a risk ratio of 1.2–7.7.

▶ Valproate exposure in pregnancy is associated with an increased risk of fetal anomalies, including neural tube defects, fetal valproate syndrome, and longterm adverse neurocognitive effects. It should be avoided in pregnancy, if possible, especially during the first trimester.

▶ Carbamazepine exposure in pregnancy is associated with fetal carbamazepine syndrome. It should be avoided in pregnancy, if possible, especially during the first trimester.

▶ Maternal benzodiazepine use shortly before delivery is associated with floppy infant syndrome.

The following recommendations and conclusions are based on limited or inconsistent scientific evidence (Level B):

▶ Paroxetine use in pregnant women and women planning pregnancy should be avoided, if possible. Fetal echocardiography should be considered for women who are exposed to paroxetine in early pregnancy.

▶ Prenatal benzodiazepine exposure increased the risk of oral cleft, although the absolute risk increased by 0.01%.

▶ Lamotrigine is a potential maintenance therapy option for pregnant women with bipolar disorder because of its protective effects against bipolar depression, general tolerability, and a growing reproductive safety profile relative to alternative mood stabilizers.

▶ Maternal psychiatric illness, if inadequately treated or untreated, may result in poor compliance with prenatal care, inadequate nutrition, exposure to additional medication or herbal remedies, increased alcohol and tobacco use, deficits in mother-infant bonding, and disruptions within the family environment.

The following recommendations and conclusions are based primarily on consensus and expert opinion (Level C):

▶ Whenever possible, multidisciplinary management involving the patient's obstetrician, mental health clinician, primary health care provider, and pediatrician is recommended to facilitate care.

▶ Use of a single medication at a higher dose is favored over the use of multiple medications for the treatment of psychiatric illness during pregnancy.

▶ The physiologic alterations of pregnancy may affect the absorption, distribution, metabolism, and elimination of lithium, and close monitoring of lithium levels during pregnancy and postpartum is recommended.

▶ For women who breastfeed, measuring serum levels in the neonate is not recommended.

▶ Treatment with all SSRIs or selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors or both during pregnancy should be individualized.

▶ Fetal assessment with fetal echocardiogram should be considered in pregnant women exposed to lithium in the first trimester.

The MEDLINE database, the Cochrane Library, and ACOG's own internal resources and documents were used to conduct a literature search to locate relevant articles published between January 1985 and June 2007. The search was restricted to articles published in the English language. Priority was given to articles reporting results of original research, although review articles and commentaries also were consulted. Abstracts of research presented at symposia and scientific conferences were not considered adequate for inclusion in this document. Guidelines published by organizations or institutions such as the National Institutes of Health and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists were reviewed, and additional studies were located by reviewing bibliographies of identified articles. When reliable research was not available, expert opinions from obstetrician-gynecologists were used.

Studies were reviewed and evaluated for quality according to the method outlined by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force:

I Evidence obtained from at least one properly designed randomized controlled trial.

II-1 Evidence obtained from well-designed controlled trials without randomization.

II-2 Evidence obtained from well-designed cohort or case-control analytic studies, preferably from more than one center or research group.

II-3 Evidence obtained from multiple time series with or without the intervention. Dramatic results in uncontrolled experiments also could be regarded as this type of evidence.

III Opinions of respected authorities, based on clinical experience, descriptive studies, or reports of expert committees.

Based on the highest level of evidence found in the data, recommendations are provided and graded according to the following categories:

Level A—Recommendations are based on good and consistent scientific evidence.

Level B—Recommendations are based on limited or inconsistent scientific evidence.

Level C—Recommendations are based primarily on consensus and expert opinion.

1 Doering PL, Stewart RB. The extent and character of drug consumption during pregnancy. JAMA 1978; 239: 843– 6. ( Level III)Crossref, Google Scholar

2 Hostetter A, Ritchie JC, Stowe ZN. Amniotic fluid and umbilical cord blood concentrations of antidepressants in three women. Biol Psychiatry 2000; 48( 10): 1032– 4. ( Level III)Crossref, Google Scholar

3 Newport DJ, Hostetter A, Arnold A, Stowe ZN. The treatment of postpartum depression: minimizing infant exposures. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002; 63 ( SuppI 7): 31– 44. ( Level III)Crossref, Google Scholar

4 Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, Nelson CB, Hughes M, Eshleman S, et al. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States. Results from the National Comorbidity Survey. A. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1994; 51: 8– 19. ( Level II-3)Crossref, Google Scholar

5 National Institute of Mental Health (US). The numbers count: mental disorders in America. NIH Publication No. 06-4584. Bethesda (MD): NIMH; 2006. Available at: http://www.nimh.nih.gov/publicat/numbers.cfm. Retrieved December 12, 2006. (Level II-3)Google Scholar

6 Weissman M, Olfson M. Depression in women: implications for health care research. Science 1995; 269: 799– 801. ( Level III)Crossref, Google Scholar

7 American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-IV-TR 4th ed. text version. Washington, DC: APA; 2000. ( Level III)Google Scholar

8 O'Hara MW, Neunaber DJ, Zekoski EM. Prospective study of postpartum depression: prevalence, course and predictive factors. J Abnorm Psychol 1984; 93: 158– 71. ( Level II-3)Crossref, Google Scholar

9 Gotlib IH, Whiffen VE, Mount JH, Milne K, Cordy NI. Prevalence rates and demographic characteristics associated with depression in pregnancy and the postpartum. J Consult Clin Psychol 1989; 57: 269– 74. ( Level III)Crossref, Google Scholar

10 Affonso DD, Lovett S, Paul SM, Sheptak S. A standardized interview that differentiates pregnancy and postpartum symptoms from perinatal clinical depression. Birth 1990; 17: 121– 30. ( Level II-3)Crossref, Google Scholar

11 Kumar R, Robson K. A prospective study of emotional disorders in childbearing women. Br J Psychiatry 1984; 144: 35– 47. ( Level II-3)Crossref, Google Scholar

12 Hostetter A, Stowe ZN, Strader JR Jr, McLaughlin E, Llewellyn A. Dose of selective serotonin uptake inhibitors across pregnancy: clinical implications. Depress Anxiety 2000; 11: 51– 7. ( Level III-3)Crossref, Google Scholar

13 Cohen LS, Altshuler LL, Harlow BL, Nonacs R, Newport DJ, Viguera AC, et al. Relapse of major depression during pregnancy in women who maintain or discontinue antidepressant treatment [published erratum appears in JAMA 2006;296:170]. J. JAMA 2006; 295: 499– 507. ( Level II-2)Crossref, Google Scholar

14 Cox J. Postnatal mental disorder: towards ICD-11. World Psychiatry 2004; 3: 96– 7. ( Level III)Google Scholar

15 Stowe ZN, Hostetter AL, Newport DJ. The onset of post-partum depression: implications for clinical screening in obstetrical and primary care. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2005; 192: 522– 6. ( Level II-3)Crossref, Google Scholar

16 Watson JP, Elliott SA, Rugg AJ, Brough DI. Psychiatric disorder in pregnancy and the first postnatal year. Br J Psychiatry 1984; 144: 453– 62. ( Level II-3)Crossref, Google Scholar

17 Evans J, Heron J, Francomb H, Oke S, Golding J. Cohort study of depressed mood during pregnancy and after childbirth. BMJ 2001; 323: 257– 60. ( Level II-2)Crossref, Google Scholar

18 Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R. Detection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Br J Psychiatry 1987; 150: 782– 6. ( Level III)Crossref, Google Scholar

19 Murray L, Carothers AD. The validation of the Edinburgh Post-natal Depression Scale on a community sample. Br J Psychiatry 1990; 157: 288– 90. ( Level III)Crossref, Google Scholar

20 Hoffman S, Hatch MC. Depressive symptomatology during pregnancy: evidence for an association with decreased fetal growth in pregnancies of lower social class women. H. Health Psychol 2000; 19: 535– 43. ( Level II-2)Crossref, Google Scholar

21 Field T, Diego MA, Dieter J, Hernandez-Reif M, Schanberg S, Kuhn C, et al. Depressed withdrawn and intrusive mothers' effects on their fetuses and neonates. Infant Behav Dev 2001; 24: 27– 39. ( Level II-2)Crossref, Google Scholar

22 Zuckerman B, Bauchner H, Parker S, Cabral H. Maternal depressive symptoms during pregnancy, and newborn irritability. J Dev Behav Pediatr 1990; 11: 190– 4. ( Level II-3)Crossref, Google Scholar

23 Zuckerman B, Amaro H, Bauchner H, Cabral H. Depressive symptoms during pregnancy: relationship to poor health behaviors. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1989; 160: 1107– 11. ( Level II-2)Crossref, Google Scholar

24 Zuckerman B, Frank DA, Hingson R, Amaro H, Levenson SM, Kayne H, et al. Effects of maternal marijuana and cocaine use on fetal growth. N Engl J Med 1989; 320: 762– 8. ( Level II-3)Crossref, Google Scholar

25 Rosett HL, Weiner L, Lee A, Zuckerman B, Dooling E, Oppenheimer E. Patterns of alcohol consumption and fetal development. Obstet Gynecol 1983; 61: 539– 46. ( Level II-2)Google Scholar

26 Sexton M, Hebel JR. A clinical trial of change in maternal smoking and its effect on birth weight. JAMA 1984; 251: 911– 5. ( Level I)Crossref, Google Scholar

27 Weissman MM, Prusoff BA, Gammon GD, Merikangas KR, Leckman JF, Kidd KK. Psychopathology in the children (ages 6–18) of depressed and normal parents. J Am Acad Child Psychiatry 1984; 23: 78– 84. ( Level II-2)Crossref, Google Scholar

28 Lyons-Ruth K, Wolfe R, Lyubchik A. Depression and the parenting of young children: making the case for early preventive mental health services. Harv Rev Psychiatry 2000; 8: 148– 53. ( Level III)Crossref, Google Scholar

29 Judd LL, Akiskal HS. The prevalence and disability of bipolar spectrum disorders in the US population: reanalysis of the ECA database taking into account sub-threshold cases. J. J Affect Disord 2003; 73: 123– 31. ( Level II-3)Crossref, Google Scholar

30 Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication [published erratum appears in Arch Gen Psychiatry 2005;62:709]. A. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2005; 62: 617– 627. ( Level II-3)Crossref, Google Scholar

31 Robins LN, Helzer JE, Weissman MM, Orvaschel H, Gruenberg E, Burke JD Jr, et al. Lifetime prevalence of specific psychiatric disorders in three sites. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1984; 41: 949– 58. ( Level II-3)Crossref, Google Scholar

32 Angst J. The course of affective disorders. II. Typology of bipolar manic-depressive illness. Arch Psychiatr Nervenkr 1978; 226: 65– 73. ( Level III)Crossref, Google Scholar

33 Yildiz A, Sachs GS. Characteristics of rapid cycling bipolar-I patients in a bipolar specialty clinic. J Affect Disord 2004; 79: 247– 51. ( Level II-3)Crossref, Google Scholar

34 McElroy SL, Keck PE Jr, Pope HG Jr, Hudson JI, Faedda GL, Swan AC. Clinical and research implications of the diagnosis of dysphoric or mixed mania or hypomania. Am J Psychiatry 1992; 149: 1633– 44. ( Level III)Crossref, Google Scholar

35 Arnold LM, McElroy SL, Keck PE Jr. The role of gender in mixed mania. Compr Psychiatry 2000; 41: 83– 7. ( Level III)Crossref, Google Scholar

36 Akdeniz F, Vahip S, Pirildar S, Vahip I, Doganer I, Bulut I. Risk factors associated with childbearing-related episodes in women with bipolar disorder. Psychopathology 2003; 36: 234– 8. ( Level II-3)Crossref, Google Scholar

37 Freeman MP, Smith KW, Freeman SA, McElroy SL, Kmetz GE, Wright R, et al. The impact of reproductive events on the course of bipolar disorder in women. J Clin Psychiatry 2002; 63: 284– 7. ( Level III)Crossref, Google Scholar

38 Grof P, Robbins W, Alda M, Berghoefer A, Vojtechovsky M, Nilsson A, et al. Protective effect of pregnancy in women with lithium-responsive bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord 2000; 61: 31– 9. ( Level III)Crossref, Google Scholar

39 Viguera AC, Nonacs R, Cohen LS, Tondo L, Murray A, Baldessarini RJ. Risk of recurrence of bipolar disorder in pregnant and nonpregnant women after discontinuing lithium maintenance. Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157: 179– 84. ( Level II-2)Crossref, Google Scholar

40 Kendall RE, Chalmers JC, Platz C. Epidemiology of puerperal psychosis [published erratum appears in Br J Psychiatry 1987;151:135]. Br J Psychiatry 1987; 150: 662– 673. ( Level II-2)Crossref, Google Scholar

41 Marks MN, Wieck A, Checkley SA, Kumar R. Contribution of psychological and social factors to psychotic and non-psychotic relapse after childbirth in women with previous histories of affective disorder. J. J Affect Disord 1992; 24: 253– 63. ( Level II-2)Crossref, Google Scholar

42 Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication [published erratum appears in Arch Gen Psychiatry 2005;62:768]. A. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2005; 62: 593– 602. ( Level II-3)Crossref, Google Scholar

43 Boyles SH, Ness RB, Grisso JA, Markovic N, Bromberger J, CiFelli D. Life event stress and the association with spontaneous abortion in gravid women at an urban emergency department. Health Psychol 2000; 19: 510– 4. ( Level II-2)Crossref, Google Scholar

44 Berkowitz GS, Kasl SV. The role of psychosocial factors in spontaneous preterm delivery. J Psychosom Res 1983; 27: 283– 90. ( Level II-2)Crossref, Google Scholar

45 Perkin MR, Bland JM, Peacock JL, Anderson HR. The effect of anxiety and depression during pregnancy on obstetric complications. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1993; 100: 629– 34. ( Level II-2)Crossref, Google Scholar

46 Pagel MD, Smilkstein G, Regen H, Montano D. Psychosocial influences on new born outcomes: a controlled prospective study. Soc Sci Med 1990; 30: 597– 604. ( Level II-2)Crossref, Google Scholar

47 Taylor A, Fisk NM, Glover V. Mode of delivery and subsequent stress response. Lancet 2000; 355: 120. ( Level II-2)Crossref, Google Scholar

48 Northcott CJ, Stein MB. Panic disorder in pregnancy. J Clin Psychiatry 1994; 55: 539– 42. ( Level III)Google Scholar

49 Cohen LS, Sichel DA, Dimmock JA, Rosenbaum JF. Postpartum course in women with preexisting panic disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 1994; 55: 289– 92. ( Level III)Google Scholar

50 Loveland Cook CA, Flick LH, Homan SM, Campbell C, McSweeney M, Gallagher ME. Posttraumatic stress disorder during pregnancy: prevalence, risk factors, and treatment. Obstet Gynecol 2004; 103: 710– 7. ( Level II-3)Crossref, Google Scholar

51 Neziroglu F, Anemone R, Yaryura-Tobias JA. Onset of obsessive-compulsive disorder in pregnancy. Am J Psychiatry 1992; 149: 947– 50. ( Level III)Crossref, Google Scholar

52 Goldstein DJ, Corbin LA, Fung MC. Olanzapine-exposed pregnancies and lactation: early experience. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2000; 20: 399– 403. ( Level III)Crossref, Google Scholar

53 Bennedsen BE, Mortensen PB, Olesen AV, Henriksen TB. Preterm birth and intra-uterine growth retardation among children of women with schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry 1999; 175: 239– 45. ( Level II-2)Crossref, Google Scholar

54 Nilsson E, Lichtenstein P, Cnattingius S, Murray RM, Hultman CM. Women with schizophrenia: pregnancy outcome and infant death among their offspring. Schizophr Res 2002; 58: 221– 9. ( Level II-2)Crossref, Google Scholar

55 Jablensky AV, Morgan V, Zubrick SR, Bower C, Yellachich LA. Pregnancy, delivery, and neonatal complications in a population cohort of women with schizophrenia and major affective disorders. Am J Psychiatry 2005; 162( 1): 79– 91. ( Level II-2)Crossref, Google Scholar

56 Bennedsen BE, Mortensen PB, Olesen AV, Henriksen TB, Frydenberg M. Obstetric complications in women with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 2001; 47: 167– 75. ( Level II-2)Crossref, Google Scholar

57 Coons PM, Ascher-Svanum H, Bellis K. Self-amputation of the female breast. Psychosomatics 1986; 27: 667– 8. ( Level III)Crossref, Google Scholar

58 Yoldas Z, Iscan A, Yoldas T, Ermete L, Akyurek C. A woman who did her own caesarean section. Lancet 1996; 348: 135. ( Level III)Crossref, Google Scholar

59 Slayton RI, Soloff PH. Psychotic denial of third-trimester pregnancy. J Clin Psychiatry 1981; 42: 471– 3. ( Level III)Google Scholar

60 Bucove AD. A case of prepartum psychosis and infanticide. Psychiatr Q 1968; 42: 263– 70. ( Level III)Crossref, Google Scholar

61 Mendlowicz MV, da Silva Filho JF, Gekker M, de Moraes TM, Rapaport MH, Jean-Louis F. Mothers murdering their newborns in the hospital. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2000; 22: 53– 5. ( Level III)Crossref, Google Scholar

62 Wen SW, Yang Q, Garner P, Fraser W, Olatunbosun O, Nimrod C, et al. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and adverse pregnancy outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2006; 194: 961– 6. ( Level II-2)Crossref, Google Scholar

63 Malm H, Klaukka T, Neuvonen PJ. Risks associated with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 2005; 106: 1289– 96. ( Level II-2)Crossref, Google Scholar

64 Einarson TR, Einarson A. Newer antidepressants in pregnancy and rates of major malformations: a meta-analysis of prospective comparative studies. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2005; 14: 823– 7. ( Meta-analysis)Crossref, Google Scholar

65 Louik C, Lin AE, Werler MM, Hernandez-Diaz S, Mitchell AA. First-trimester use of selective serotoninreuptake inhibitors and the risk of birth defects. NEJM 2007; 356: 2675– 83. ( Level II-2)Crossref, Google Scholar

66 Alwan S, Reefhuis J, Rasmussen SA, Olney RS, Friedman JM. Use of selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors in pregnancy and the risk of birth defects. National Birth Defects Prevention Study. N. NEJM 2007; 356: 2684– 92. ( Level II-2)Crossref, Google Scholar

67 Moses-Kolko EL, Bogen D, Perel J, Bregar A, Uhl K, Levin B, et al. Neonatal signs after late in utero exposure to serotonin reuptake inhibitors: literature review and implications for clinical applications. J. JAMA 2005; 293: 2372– 83. ( Level III)Crossref, Google Scholar

68 Chambers CD, Johnson KA, Dick LM, Felix RJ, Jones KL. Birth outcomes in pregnant women taking fluoxetine. N Engl J Med 1996; 335: 1010– 15. ( Level II-2)Crossref, Google Scholar

69 Costei AM, Kozer E, Ho T, Ito S, Koren G. Perinatal outcome following third trimester exposure to paroxetine. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2002; 156: 1129– 32. ( Level II-2)Crossref, Google Scholar

70 Kallen B. Neonate characteristics after maternal use of antidepressants in late pregnancy. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2004; 158: 312– 316. ( Level II-2)Crossref, Google Scholar

71 Zeskind PS, Stephens LE. Maternal selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor use during pregnancy and newborn neurobehavior. Pediatrics 2004; 113: 368– 75. ( Level II-2)Crossref, Google Scholar

72 Chambers CD, Hernandez-Diaz S, Van Marter LJ, Werler MM, Louik C, Jones KL, et al. Selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors and risk of persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn. N Engl J Med 2006; 354: 579– 87. ( Level II-2)Crossref, Google Scholar

73 Barson AJ. Malformed infant. Br Med J 1972; 2: 45. ( Level III)Crossref, Google Scholar

74 Elia J, Katz IR, Simpson GM. Teratogenicity of psycho-therapeutic medications. Psychopharmacol Bull 1987; 23: 531– 86. ( Level III)Google Scholar

75 McBride WG. Limb deformities associated with iminodibenzyl hydrochloride. Med J Austr 1972; 1: 492. ( Level III)Google Scholar

76 Altshuler LL, Cohen L, Szuba MP, Burt VK, Gitlin M, Mintz J. Pharmacologic management of psychiatric illness during pregnancy: dilemmas and guidelines. Am J Psychiatry 1996; 153: 592– 606. ( Level III)Crossref, Google Scholar

77 McElhatton PR, Garbis HM, Elefant E, Vial T, Bellemin B, Mastroiacovo P, et al. The outcome of pregnancy in 689 women exposed to therapeutic doses of antidepressants. A collaborative study of the European Network of Teratology Information Services (ENTIS). R. Reprod Toxicol 1996; 10: 285– 94. ( Level III)Crossref, Google Scholar

78 Nulman I, Rovet J, Stewart DE, Wolpin J, Gardner HA, Theis JA et al. Neurodevelopment of children exposed in utero to antidepressant drugs. N Engl J Med 1997; 336: 258– 62. ( Level II-2)Crossref, Google Scholar

79 Prentice A, Brown R. Fetal tachyarrhythmia and maternal antidepressant treatment. BMJ 1989; 298: 190. ( Level III)Crossref, Google Scholar

80 Eggermont E. Withdrawal symptoms in neonates associated with maternal imipramine therapy. Lancet 1973; 2: 680. ( Level III)Crossref, Google Scholar

81 Miller LJ. Clinical strategies for the use of psychotropic drugs during pregnancy. Psychiatr Med 1991; 9: 275– 98. ( Level III)Google Scholar

82 Webster PA. Withdrawal symptoms in neonates associated with maternal antidepressant therapy. Lancet 1973; 2: 318– 9. ( Level III)Crossref, Google Scholar

83 Misri S, Sivertz K. Tricyclic drugs in pregnancy and lactation: a preliminary report. Int J Psychiatry Med 1991; 21: 157– 71. ( Level II-3)Crossref, Google Scholar

84 Simon GE, Cunningham ML, Davis RL. Outcomes of prenatal antidepressant exposure. Am J Psychiatry 2002; 159: 2055– 61. ( Level II-2)Crossref, Google Scholar

85 Yaris F, Kadioglu M, Kesim M, Ulku C, Yaris E, Kalyoncu NI, et al. Newer antidepressants in pregnancy: prospective outcome of a case series. Reprod Toxicol 2004; 19: 235– 8. ( Level II-3)Crossref, Google Scholar

86 Yaris F, Ulku C, Kesim M, Kadioglu M, Unsal M, Dikici MF, et al. Psychotropic drugs in pregnancy: a case-control study. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 2005; 29: 333– 8. ( Level II-2)Crossref, Google Scholar

87 Kesim M, Yaris F, Kadioglu M, Yaris E, Kalyoncu NI, Ulku C. Mirtazapine use in two pregnant women: is it safe? Teratology 2002; 66: 204. ( Level III)Google Scholar

88 Rohde A, Dembinski J, Dom C. Mirtazapine (Remergil) for treatment resistant hyperemesis gravidarum: rescue of a twin pregnancy. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2003; 268: 219– 21. ( Level III)Crossref, Google Scholar

89 Einarson A, Bonari L, Voyer-Lavigne S, Addis A, Matsui D, Johnson Y, et al. A multicentre prospective controlled study to determine the safety of trazodone and nefazodone use during pregnancy. Can J Psychiatry 2003; 48: 106– 10. ( Level II-2)Crossref, Google Scholar

90 Chun-Fai-Chan B, Koren G, Fayez I, Kalra S, Voyer-Lavigne S, Boshier A, et al. Pregnancy outcome of women exposed to bupropion during pregnancy: a prospective comparative study. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2005; 192: 932– 6. ( Level II-2)Crossref, Google Scholar

91 Miller LJ. Use of electroconvulsive therapy during pregnancy. Hosp Community Psychiatry 1994; 45: 444– 50. ( Level III)Google Scholar

92 Rabheru K. The use of electroconvulsive therapy in special patient populations. Can J Psychiatry 2001; 46: 710– 9. ( Level III)Crossref, Google Scholar

93 Nora JJ, Nora AH, Toews WH. Lithium, Ebstein's anomaly, and other congenital heart defects [letter]. Lancet 1974; 2: 594– 5. ( Level III)Crossref, Google Scholar

94 Weinstein MR, Goldfield M. Cardiovascular malformations with lithium use during pregnancy. Am J Psychiatry 1975; 132: 529– 31. ( Level III)Crossref, Google Scholar

95 Cohen LS, Friedman JM, Jefferson JW, Johnson EM, Weiner ML. A reevaluation of risk of in utero exposure to lithium [published erratum appears in JAMA 1994;271: [485]. JAMA 1994; 271: 146– 50. ( Level III)Crossref, Google Scholar

96 Kallen B, Tandberg A. Lithium and pregnancy. A cohort of manic-depressive women. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1983; 68: 134– 9. ( Level II-2)Crossref, Google Scholar

97 Jacobson SJ, Jones K, Johnson K, Ceolin L, Kaur P, Sahn D, et al. Prospective multicentre study of pregnancy outcome after lithium exposure during first trimester. Lancet 1992; 339: 530– 3. ( Level II-2)Crossref, Google Scholar

98 Friedman JM, Polifka JE. Teratogenic effects of drugs: a resource for clinicians (TERIS). 2nd ed. Baltimore (MD): Johns Hopkins University Press; 2000. ( Level III)Google Scholar

99 Wilson N, Forfar JC, Godman MJ. Atrial flutter in the newborn resulting from maternal lithium ingestion. Arch Dis Child 1983; 58: 538– 9. ( Level III)Crossref, Google Scholar

100 Mizrahi EM, Hobbs JF, Goldsmith DI. Nephrogenic diabetes insipidus in transplacental lithium intoxication. J Pediatr 1979; 94: 493– 5. ( Level III)Crossref, Google Scholar

101 Karlsson K, Lindstedt G, Lundberg PA, Selstam U. Transplacental lithium poisoning: reversible inhibition of fetal thyroid [letter]. Lancet 1975; 1: 1295. ( Level III)Crossref, Google Scholar

102 Llewellyn A, Stowe ZN, Strader JR Jr. The use of lithium and management of women with bipolar disorder during pregnancy and lactation. J Clin Psychiatry 1998; 59( suppl 6): 57– 64; discussion 65. (Level III)Google Scholar

103 Woody JN, London WL, Wilbanks GD Jr. Lithium toxicity in a newborn. Pediatrics 1971; 47: 94– 6. ( Level III)Google Scholar

104 Schou M. What happened later to the lithium babies? A follow-up study of children born without malformations. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1976; 54: 193– 7. ( Level II-2)Crossref, Google Scholar

105 Holmes LB, Harvey EA, Coull BA, Huntington KB, Khoshbin S, Hayes AM. The teratogenicity of anticonvulsant drugs. N Engl J Med 2001; 344: 1132– 8. ( Level II-2)Crossref, Google Scholar

106 Jager-Roman E, Deichl A, Jakob S, Hartmann AM, Koch S, Rating D, et al. Fetal growth, major malformations, and minor anomalies in infants born to women receiving valproic acid. J Pediatr 1986; 108: 997– 1004. ( Level II-2)Crossref, Google Scholar

107 Lindhout D, Schmidt D. In-utero exposure to valproate and neural tube defects. Lancet 1986; 1: 1392– 3. ( Level III-3)Crossref, Google Scholar

108 Spina bifida incidence at birth-United States, 1983-1990. Centers for Disease Control (CDC). MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 1992; 41: 497– 500. ( Level II-3)Google Scholar

109 Samren E, van Duijn CM, Koch S, Hiilesmaa VK, Klepel H, Bardy AH, et al. Maternal use of antiepileptic drugs and the risk of major congenital malformations: a joint European prospective study of human teratogenesis associated with maternal epilepsy. E. Epilepsia 1997; 38: 981– 90. ( Level II-2)Crossref, Google Scholar

110 Omtzigt JG, Los FJ, Meiger JW, Lindhout D. The 10, 11-epoxide-10, 11-diol pathway of carbamazepine in early pregnancy in maternal serum, urine, and amniotic fluid: effect of dose, comedication, and relation to outcome of pregnancy. T. Ther Drug Monit 1993; 15: 1– 10. ( Level II-3)Crossref, Google Scholar

111 Samren E, van Duijn CM, Christiaens GC, Hofman A, Lindhout D. Antiepileptic drug regimens and major congenital abnormalities in the offspring. Ann Neurol 1999; 46: 739– 46. ( Level II-2)Crossref, Google Scholar

112 Canger R, Battino D, Canevini MP, Fumarola C, Guidolin L, Vignoli A, et al. Malformations in offspring of women with epilepsy: a prospective study. Epilepsia 1999; 40: 1231– 6. ( Level II-2)Crossref, Google Scholar

113 Kaneko S, Battino D, Andermann E, Wada K, Kan R, Takeda A, et al. Congenital malformations due to antiepileptic drugs. Epilepsy Res 1999; 33: 145– 58. ( Level II-2)Crossref, Google Scholar

114 Paulson GW, Paulson RB. Teratogenic effects of anticonvulsants. Arch Neurol 1981; 38: 140– 3. ( Level III)Crossref, Google Scholar

115 Rodriguez-Pinilla E, Arroyo I, Fondevilla J, Garcia MJ, Martinez-Frias ML. Prenatal exposure to valproic acid during pregnancy and limb deficiencies: a case-control study. Am J Med Genet 2000; 90: 376– 81. ( Level II-2)Crossref, Google Scholar

116 Dalens B, Raynaud EJ, Gaulme J. Teratogenicity of valproic acid. J Pediatr 1980: 97: 332– 3. ( Level III)Crossref, Google Scholar

117 Koch S, Jager-Roman E, Rating D, Helge H. Possible teratogenic effect of valproate during pregnancy. J Pediatr 1983; 103: 1007– 8. ( Level III)Crossref, Google Scholar

118 Sodhi P, Poddar B, Parmar V. Fatal cardiac malformation in fetal valproate syndrome. Indian J Pediatr 2001; 68: 989– 90. ( Level III)Crossref, Google Scholar

119 Winter RM, Donnai D, Burn J, Tucker SM. Fetal valproate syndrome: is there a recognisable phenotype? J Med Genet 1987; 24: 692– 5. ( Level III)Google Scholar

120 Ardinger HH, Atkin JF, Blackston RD, Elsas LJ, Clarren SK, Livingstone S, et al. Verification of the fetal valproate syndrome phenotype. Am J Med Genet 1988; 29: 171– 85. ( Level III)Crossref, Google Scholar

121 Martinez-Frias ML. Clinical manifestation of prenatal exposure to valproic acid using case reports and epidemiologic information. Am J Med Genet 1990; 37: 277– 82. ( Level III)Crossref, Google Scholar

122 Kozma C. Valproic acid embryopathy: report of two siblings with further expansion of the phenotypic abnormalities and a review of the literature. A. Am J Med Genet 2001; 98: 168– 75. ( Level III)Crossref, Google Scholar

123 Williams PG, Hersh JH. A male with fetal valproate syndrome and autism. Dev Med Child Neurol 1997; 39: 632– 4. ( Level III)Crossref, Google Scholar

124 Moore SJ, Turnpenny P, Quinn A, Glover S, Lloyd DJ, Montgomery T, et al. A clinical study of 57 children with fetal anticonvulsant syndromes. J Med Genet 2000; 37: 489– 97. ( Level III)Crossref, Google Scholar

125 Bescoby-Chambers N, Forster P, Bates G. Foetal valproate syndrome and autism: additional evidence of an association [letter]. Dev Med Child Neurol 2001; 43: 847. ( Level III)Crossref, Google Scholar

126 Williams G, King J, Cunningham M, Stephan M, Kerr B, Hersh JH. Fetal valproate syndrome and autism: additional evidence of an association. Dev Med Child Neurol 2001; 43: 202– 6. ( Level III)Crossref, Google Scholar

127 Gaily E, Kantola-Sorsa E, Granstrom ML. Specific cognitive dysfunction in children with epileptic mothers. Dev Med Child Neurol 1990; 32: 403– 14. ( Level II-2)Crossref, Google Scholar

128 Adab N, Jacoby A, Smith D, Chadwick D. Additional educational needs in children born to mothers with epilepsy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2001; 70: 15– 21. ( Level II-2)Crossref, Google Scholar

129 Kennedy D, Koren G. Valproic acid use in psychiatry: issues in treating women of reproductive age. J Psychiatry Neurosci 1998; 23: 223– 8. ( Level III)Google Scholar

130 Mountain KR, Hirsch J, Gallus AS. Neonatal coagulation defect due to anticonvulsant drug treatment in pregnancy. Lancet 1970; 1: 265– 8. ( Level II-3)Crossref, Google Scholar

131 Thisted E, Ebbesen F. Malformations, withdrawal manifestations, and hypoglycaemia after exposure to valproate in utero. Arch Dis Child 1993; 69: 288– 91. ( Level III)Crossref, Google Scholar

132 Ebbesen F, Joergensen A, Hoseth E, Kaad PH, Moeller M, Holsteen V, et al. Neonatal hypoglycaemia and withdrawal symptoms after exposure in utero to valproate. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2000; 83: F124– 9. ( Level II-2)Crossref, Google Scholar

133 Jones KL, Lacro RV, Johnson KA, Adams J. Pattern of malformations in the children of women treated with carbamazepine during pregnancy. N Engl J Med 1989; 320: 1661– 6. ( Level II-3)Crossref, Google Scholar

134 Scolnik D, Nulman I, Rovet J, Gladstone D, Czuchta D, Gardner HA, et al. Neurodevelopment of children exposed in utero to phenytoin and carbamazepine monotherapy [published erratum appears in JAMA 1994; 271:1745]. J. JAMA 1994; 271: 767– 70. ( Level II-2)Crossref, Google Scholar

135 Wide K, Winbladh B, Tomson T, Sars-Zimmer K, Berggren E. Psychomotor development and minor anomalies in children exposed to antiepileptic drugs in utero: a prospective population-based study [published erratum appears in Dev Med Child Neurol 2000;42:356]. D. Dev Med Child Neurol 2000; 42: 87– 92. ( Level II-2)Crossref, Google Scholar

136 Ornoy A, Cohen E. Outcome of children born to epileptic mothers treated with carbamazepine during pregnancy. Arch Dis Child 1996; 75: 517– 20. ( Level II-2)Crossref, Google Scholar

137 Gaily E, Granstrom ML, Liukkonen E. Oxcarbazepine in the treatment of epilepsy in children and adolescents with intellectual disability. J Intellect Disabil Res. 1998; 42 ( suppl 1): 41– 5. ( Level III)Google Scholar

138 Van der Pol MC, Hadders-Algra M, Huisjes MJ, Touwen BC. Antiepileptic medication in pregnancy: late effects on the children's central nervous system development. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1991; 164: 121– 8. ( Level II-2)Crossref, Google Scholar

139 Matalon S, Schechtman S, Goldzweig G, Ornoy A. The teratogenic effect of carbamazepine: a meta-analysis of 1255 exposures. Reprod Toxicol 2002; 16: 9– 17. ( Meta-analysis)Crossref, Google Scholar

140 Vajda FJ, O'Brien TJ, Hitchcock A, Graham J, Lander C. The Australian registry of anti-epileptic drugs in pregnancy: experience after 30 months. J Clin Neurosci 2003; 10: 543– 9. ( Level II-2)Crossref, Google Scholar

141 Sabers A, Dam M, A-Rogvi-Hansen B, Boas J, Sidenius P, Laue Friis M, et al. Epilepsy and pregnancy: lamotrigine as main drug used. Acta Neurol Scand 2004; 109: 9– 13. ( Level III)Crossref, Google Scholar

142 Cunnington M, Tennis P. Lamotrigine and the risk of malformations in pregnancy. International Lamotrigine Pregnancy Registry Scientific Advisory Committee. N. Neurology 2005; 64: 955– 60. ( Level III)Crossref, Google Scholar

143 Holmes LB, Wyszynski DF. North American antiepileptic drug pregnancy registry. Epilepsia 2004; 45: 1465. ( Level III)Crossref, Google Scholar

144 Meador KJ, Baker GA, Finnell RH, Kalayjian LA, Liporace JD, Loring DW, et al. In utero antiepileptic drug exposure: fetal death and malformations. NEAD Study Group. Neurology 2006; 67: 407– 12. ( Level II-2)Crossref, Google Scholar

145 Morrow J, Russell A, Guthrie E, Parsons L, Robertson I, Waddell R, et al. Malformation risks of antiepileptic drugs in pregnancy: a prospective study from the UK Epilepsy and Pregnancy Register. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2006; 77: 193– 8. ( Level II-2)Crossref, Google Scholar

146 Baldessarini RJ, Faedda GL, Hennen J. Risk of mania with antidepressants. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2005; 159: 298. ( Level III)Google Scholar

147 Newport DJ, Viguera AC, Beach AJ, Ritchie JC, Cohen LS, Stowe ZN. Lithium placental passage and obstetrical outcome: implications for clinical management during late pregnancy. Am J Psychiatry 2005; 162: 2162– 70. ( Level III)Crossref, Google Scholar

148 Choulika S, Grabowski E, Holmes LB. Is antenatal vitamin K prophylaxis needed for pregnant women taking anticonvulsants? Am J Obstet Gynecol 2004; 190: 882– 3. ( Level II-2)Google Scholar

149 Saxen I. Cleft palate and maternal diphenhydramine intake [letter]. Lancet 1974; 1: 407– 8. ( Level III)Crossref, Google Scholar

150 Aarkog D. Association between maternal intake of diazepam and oral clefts [letter]. The Lancet 1975; 2: 921. ( Level II-2)Crossref, Google Scholar

151 Saxen I. Associations between oral clefts and drugs taken during pregnancy. Int J Epidemiol 1975; 4: 37– 44. ( Level II-2)Crossref, Google Scholar

152 Eros E, Czeizel AE, Rockenbauer M, Sorensen HT, Olsen J. A population-based case-control teratologic study of nitrazepam, medazepam, tofisopam, alprazolum and clonazepam treatment during pregnancy. E. Euro J Obstet, Gynecol Reprod Biol 2002; 101: 147– 54. ( Level II-2)Crossref, Google Scholar

153 Lin AE, Peller AJ, Westgate MN, Houde K, Franz A, Holmes LB. Clonazepam use in pregnancy and the risk of malformations. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol 2004; 70: 534– 6. ( Level III-3)Crossref, Google Scholar

154 Haram K. ‘Floppy infant syndrome’ and maternal diazepam. Lancet 1977; 2: 612– 3. ( Level III)Crossref, Google Scholar

155 Speight AN. Floppy-infant syndrome and maternal diazepam and/or nitrazepam. Lancet 1977; 2: 878. ( Level III)Crossref, Google Scholar

156 Woods DL, Malan AF. Side-effects of maternal diazepam on the newborn infant. S Afr Med J 1978; 54: 636. ( Level III)Google Scholar

157 Kriel RL, Cloyd J. Clonazepam and pregnancy. Ann Neurol 1982; 11: 544. ( Level III)Crossref, Google Scholar

158 McAuley DM, O'Neill MP, Moore J, Dundee JW. Lorazepam premedication for labour. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1982; 89: 149– 54. ( Level I)Crossref, Google Scholar

159 Erkkola R, Kero P, Kanto J, Aaltonen L. Severe abuse of psychotropic drugs during pregnancy with good perinatal outcome. Ann Clin Res 1983; 15: 88– 91. ( Level III)Google Scholar

160 Fisher JB, Edgren BE, Mammel MC, Coleman JM. Neonatal apnea associated with maternal clonazepam therapy: a case report. Obstet Gynecol. 1985; 66( suppl): 34s– 35s. ( Level III)Google Scholar

161 Sanchis A, Rosique D, Catala J. Adverse effects of maternal lorazepam on neonates. DICP 1991; 25: 1137– 8. ( Level III)Google Scholar

162 Whitelaw AG, Cummings AJ, McFadyen IR. Effect of maternal lorazepam on the neonate. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1981; 282: 1106– 8. ( Level II-2)Crossref, Google Scholar

163 Barry WS, St Clair S. Exposure to benzodiazepines in utero. Lancet 1987; 1: 1436– 7. ( Level III)Crossref, Google Scholar

164 Bitnun S. Possible effect of chlordiazepoxide on the fetus. Can Med Assoc J 1969; 100: 351. ( Level III)Google Scholar

165 Stirrat GM, Edington PT, Berry DJ. Transplacental passage of chlordiazepoxide [letter]. Br Med J 1974; 2: 729. ( Level III)Crossref, Google Scholar

166 Athinarayanan P, Pierog SH, Nigam SK, Glass L. Chloriazepoxide withdrawal in the neonate. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1976; 124: 212– 3. ( Level III)Crossref, Google Scholar

167 Mazzi E. Possible neonatal diazepam withdrawal: a case report. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1977; 129: 586– 7. ( Level III)Crossref, Google Scholar

168 Backes CR, Cordero L. Withdrawal symptoms in the neonate from presumptive intrauterine exposure to diazepam: report of case. J Am Osteopath Assoc 1980; 79: 584– 5. ( Level III)Google Scholar

169 Laegreid L, Olegard R, Wahlstrom J, Conradi N. Abnormalities in children exposed to benzodiazepines in utero. Lancet 1987; 1: 108– 109. ( Level III)Crossref, Google Scholar

170 Gerhardsson M, Alfredsson L. In utero exposure to benzodiazepines [letter]. Lancet 1987: 628. ( Level III)Google Scholar

171 Winter RM. In-utero exposure to benzodiazepines [letter]. Lancet 1987; 1: 627. ( Level III)Crossref, Google Scholar

172 Hartz SC, Heinonen OP, Shapiro S, Siskind V, Slone D. Antenatal exposure to meprobamate and chlordiazepoxide in relation to malformations, mental development, and childhood mortality. N Engl J Med 1975; 292: 726– 8. ( Level II-2)Crossref, Google Scholar

173 McKenna K, Koren G, Tetelbaum M, Wilton L, Shakir S, Diav-Citrin O, et al. Pregnancy outcome of women using atypical antipsychotic drugs: a prospective comparative study. J Clin Psychiatry 2005; 66: 444– 9; quiz 546. (Level III-3)Crossref, Google Scholar

174 Goldberg HL, DiMascio A. Psychotropic drugs in pregnancy. In: Lipton MA, DiMascio A, Killam KF, editors. Psychopharmacology: a generation of progress. New York (NY): Raven Press; 1978. p. 1047– 55. ( Level III)Google Scholar

175 Hill RM, Stern L. Drugs in pregnancy: effects on the fetus and newborn. Drugs 1979; 17: 182– 97. ( Level III)Crossref, Google Scholar

176 Numberg HG, Prudic J. Guidelines for treatment of psychosis during pregnancy. Hosp Community Psychiatry 1984; 35: 67– 71. ( Level III)Google Scholar

177 Van Waes A, Van de Velde E. Safety evaluation of haloperidol in the treatment of hyperemesis gravidarum. J Clin Pharmacol 1969; 9: 224– 7. ( Level II-2)Google Scholar

178 Miklovich L, van den Berg BJ. An evaluation of the teratogenicity of certain antinauseant drugs. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1976; 125: 244– 8. ( Level II-2)Crossref, Google Scholar

179 Moriarty AJ, Nance NR. Trifluoperazine and pregnancy [letter]. Can Med Assoc J 1963; 88: 375– 6. ( Level III)Google Scholar

180 Rawlings WJ. Use of medroxyprogesterone in the treatment of recurrent abortion. Med J Aust 1963; 50: 183– 4. ( Level III)Google Scholar

181 Rumeau-Rouquette C, Goujard J, Huel G. Possible teratogenic effect of phenothiazines in human beings. Teratology 1977; 15: 57– 64. ( Level II-2)Crossref, Google Scholar

182 Edlund MJ, Craig TJ. Antipsychotic drug use and birth defects: an epidemiologic reassessment. Compr Psychiatry 1984; 25: 32– 7. ( Level II-2)Crossref, Google Scholar

183 Kris EB. Children of mothers maintained on pharmacotherapy during pregnancy and postpartum. Curr Ther Res Clin Exp 1965; 7: 785– 9. ( Level III)Google Scholar

184 Slone D, Siskind V, Heinonen OP, Monson RR, Kaufman DW, Shapiro S. Antenatal exposure to the phenothiazines in relation to congenital malformations, perinatal mortality rate, birth weight, and intelligence quotient score. A. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1977; 128: 486– 8. ( Level II-2)Crossref, Google Scholar

185 James ME. Neuroleptic malignant syndrome in pregnancy. Psychosomatics 1988; 29: 119– 22. ( Level III)Crossref, Google Scholar

186 Collins KO, Comer JB. Maternal haloperidol therapy associated with dyskinesia in a newborn. Am J Health Syst Pharm 2003; 60: 2253– 5. ( Level III)Crossref, Google Scholar

187 Hill RM, Desmond MM, Kay JL. Extrapyramidal dysfunction in an infant of a schizophrenic mother. J Pediatr 1966; 69: 589– 95. ( Level III)Crossref, Google Scholar

188 Scokel PW 3rd, Jones WN. Infant jaundice after phenothiazine drugs for labor: an enigma. Obstet Gynecol 1962; 20: 124– 7. ( Level II-2)Crossref, Google Scholar

189 Falterman CG, Richardson CJ. Small left colon syndrome associated with maternal ingestion of psychotropic drugs. J Pediatr 1980; 97: 308– 10. ( Level III)Crossref, Google Scholar

190 Heinonen OP, Shapiro S, Slone D. Birth defects and drugs in pregnancy. Littleton (MA): Publishing Sciences Group; 1977. ( Level III)Google Scholar

191 Nelson MM, Forfar JO. Associations between drugs administered during pregnancy and congenital abnormalitics of the fetus. Br Med J 1971; 1: 523– 7. ( Level III)Crossref, Google Scholar

192 Hale TW. Medications in Mother's Milk. Amaraillo (TX): Pharmasoft Publishing, 2004. ( Level III)Google Scholar

193 Stowe ZN, Owens MJ, Landry JC, Kilts CD, Ely T, Llewellyn A, et al. Sertraline and desmethylsertraline in human breast milk and nursing infants. Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154: 1255– 60. ( Level II-3)Crossref, Google Scholar

194 Altshuler LL, Burt VK, McMullen M, Hendrick V. Breastfeeding and sertraline: a 24-hour analysis. J Clin Psychiatry 1995; 56: 243– 5. ( Level III)Google Scholar