Practice Parameter for the Assessment and Treatment of Children and Adolescents With Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder

Abstract

This practice parameter describes the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) based on the current scientific evidence and clinical consensus of experts in the field. This parameter discusses the clinical evaluation for ADHD, comorbid conditions associated with ADHD, research on the etiology of the disorder, and psychopharmacological and psychosocial interventions for ADHD.

(Reprinted with permission from the Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 2007; 46(7):894–921)

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD; American Psychiatric Association, 2000) is one of the most common childhood psychiatric conditions. It has been the focus of a great deal of scientific and clinical study during the past century. Upon reviewing the voluminous literature on ADHD, the American Medical Association's Council on Scientific Affairs (Goldman et al., 1998) commented, “Overall, ADHD is one of the best-researched disorders in medicine, and the overall data on its validity are far more compelling than for many medical conditions.” Although scientists and clinicians debate the best way to diagnose and treat ADHD, there is no debate among competent and well-informed health care professionals that ADHD is a valid neurobiological condition that causes significant impairment in those whom it afflicts. These guidelines seek to lay out evidence-based guidelines for the effective diagnosis and treatment of ADHD.

In this parameter, the term preschoolers refers to children ages 3 through 5 years, the term children refers to children ages 6 through 12 years, and the term adolescents refers to minors ages 13 through 17 years. Parent refers to parent or legal guardian. Patient refers to any minor with ADHD. The terminology in this practice parameter is consistent with that of DSM-IV-TR (American Psychiatric Association, 2000).

METHODOLOGY

The list of references for this parameter was developed by searching PsycINFO, Medline, and Psychological Abstracts; by reviewing the bibliographies of book chapters and review articles; by asking colleagues for suggested source materials; and from the previous version of this parameter. The searches were conducted from September 2004 through April 2006 for articles in English using the key word “attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.” The search covered the period 1996 to 2006 and yielded approximately 5,000 references. Recent authoritative reviews of literature, as well as recent treatment studies that were in press or presented at scientific meetings in the past 2 to 3 years, were given priority for inclusion. The titles and abstracts of the remaining references were reviewed for particular relevance and selected for inclusion when the reference appeared to inform the field on the diagnosis and/or treatment of ADHD.

EPIDEMIOLOGY AND CLINICAL COURSE

Recently, epidemiological studies have more precisely defined the prevalence of ADHD and the extent of its treatment with medication. Rowland et al. (2002) surveyed more than 6,000 parents of elementary school children in a North Carolina county. Ten percent of the children had been given a diagnosis of ADHD and 7% were taking medication for ADHD. Parents of 2,800 third through fifth graders were surveyed in Rhode Island; 12% of parents reported that their child had been referred for evaluation and 6% were receiving medication (Harel and Brown, 2003). An epidemiological study of nearly 6,000 children in Rochester, MN, found a cumulative incidence of ADHD in the elementary and secondary school population of 7.5% (95% confidence interval 6.5–8.4; Barbaresi et al., 2002), which was similar to a 6.7% prevalence of ADHD found by the U.S. National Health Interview Survey for the period 1997-2000 (Woodruff et al., 2004). The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2005) conducted the National Survey of Children's Health during January 2003–2004, asking parents of more than 100,000 children ages 4 to 17 years whether their child had ever been diagnosed with ADHD or received medication treatment (as opposed to currently being treated). The rate of lifetime childhood diagnosis of ADHD was 7.8%, whereas 4.3% (or only 55% of those with ADHD) had ever been treated with medication for the disorder.

Follow-up studies have begun to delineate the life course of ADHD. A majority (60%–85%) of children with ADHD will continue to meet criteria for the disorder during their teenage years (Barkley et al., 1990; Biederman et al., 1996; Claude and Firestone, 1995), clearly establishing that ADHD does not remit with the onset of puberty alone. Defining the number of children with ADHD who continue to have problems as adults is more difficult because of methodological issues reviewed by Barkley (2002). These include changes in informant (parent versus child), use of different instruments to diagnose ADHD in adults, comorbidity of the other psychiatric disorders in the childhood sample (less comorbid samples have better outcome), and issues with the DSM-IV diagnostic criteria themselves. The criteria are designed for school-age children with regard to the number of symptoms required to meet the diagnostic threshold (i.e., six of the nine symptoms for inattention and/or hyperactivity/impulsivity), which may be developmentally inappropriate for adults. That is, an adult may suffer significant impairment even though he or she suffers from fewer than six of nine symptoms in these areas. The persistence of the full syndrome of ADHD in young adulthood has been found to range from 2% to 8% when self-report is used (Barkley et al., 2002; Mannuzza et al., 1993). In contrast, when parent report is used, the prevalence increases to 46% and when a developmental definition of disorder is used (98th percentile), it increases further to 67% (Barkley et al., 2002). Biederman et al. (2000) found that the rates of ADHD in adults varied according to number of symptoms and level of impairment required for the diagnostic threshold. Although only 40% of 18- to 20-year-old “grown up” ADHD patients met the full criteria for ADHD, 90% had at least five symptoms of ADHD and a Global Assessment of Functioning score below 60. Faraone and Biederman (2005) performed telephone interviews with 966 adults and the prevalence of ADHD using narrow criteria (those who met full criteria and had childhood onset) was 2.9%, but 16.4% had subthreshold symptoms. Furthermore, adults with a childhood history of ADHD have higher than expected rates of antisocial and criminal behavior (Barkley et al., 2004), injuries and accidents (Barkley, 2004), employment and marital difficulties, and health problems and are more likely to have teen pregnancies (Barkley et al., 2006) and children out of wedlock (Johnston, 2002). Recently, the National Comorbidity Survey Replication screened a probability sample of 3,199 individuals ages 19 to 44 years and estimated the prevalence of adult ADHD to be 4.4% (Kessler et al., 2005). Although this practice parameter concerns the assessment and treatment of the preschooler, child, or adolescent with ADHD, it is critical to note that many children with ADHD will continue to have impairment into adulthood that will require treatment.

COMORBIDITIES

It is well established that ADHD frequently is comorbid with other psychiatric disorders (Pliszka et al., 1999). Studies have shown that 54%–84% of children and adolescents with ADHD may meet criteria for oppositional defiant disorder (ODD); a significant portion of these patients will develop conduct disorder (CD; Barkley, 2005; Faraone et al., 1997). Fifteen percent to 19% of patients with ADHD will start to smoke (Milberger et al., 1997) or develop other substance abuse disorders (Biederman et al., 1997). Depending on the precise psychometric definition, 25%–35% of patients with ADHD will have a coexisting learning or language problem (Pliszka et al., 1999), and anxiety disorders occur in up to one third of patients with ADHD (Biederman et al., 1991; MTA Cooperative Group, 1999b; Pliszka et al., 1999; Tannock, 2000). The prevalence of mood disorder in patients with ADHD is more controversial, with studies showing 0% to 33% of patients with ADHD meeting criteria for a depressive disorder (Pliszka et al., 1999). The prevalence of mania among patients with ADHD remains a contentious issue (Biederman, 1998; Klein et al., 1998). The National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Multimodal Treatment of ADHD (MTA) study (Jensen et al., 2001a) did not find it necessary to exclude any child with ADHD because of a diagnosis of bipolar disorder, but Biederman et al. (1992) found that 16% of a sample of ADHD patients met criteria for mania, although a chronic, irritable mania predominated. Comorbidity in adult ADHD patients is similar to that of children, except that antisocial personality replaces ODD or CD as the main behavioral psychopathology and mood disorders increase in prevalence (Biederman, 2004). Clinicians should be prepared to encounter a wide range of psychiatric symptoms in the course of managing patients with ADHD.

ETIOLOGY

Neuropsychological studies have shown that patients with ADHD have deficits in executive functions that are “neurocognitive processes that maintain an appropriate problem solving set to attain a future goal” (Willcutt et al., 2005). Specifically, a meta-analysis of 83 studies with more than 6,000 subjects showed that patients with ADHD have impairments in the executive functioning domains of response inhibition, vigilance, working memory, and some measures of planning (Willcutt et al., 2005). Nonetheless, not all patients with ADHD show executive function deficits, suggesting that although these deficits are a major factor in the disorder, other neuropsychological problems must be present as well. There is growing evidence that the principal cause of ADHD is genetic (Faraone et al., 2005b). Faraone et al. (2005b) reviewed 20 independent twin studies that estimated the heritability (the amount of phenotypic variance of symptoms attributed to genetic factors) to be 76%. Recent genome scan studies suggest ADHD is complex; ADHD has been associated with markers at chromosomes 4, 5, 6, 8, 11, 16, and 17 (Muenke, 2004; Smalley et al., 2004). Faraone et al. (2005b) identified eight genes in which the same variant was studied in three or more studies; seven of which showed statistically significant evidence of association with ADHD (the dopamine 4 and 5 receptors, the dopamine transporter, the enzyme dopamine β-hydroxylase, the serotonin transporter gene, the serotonin 1B receptor, and the synaptosomal-associated protein 25 gene). Nongenetic causes of ADHD are also neurobiological in nature (Nigg, 2006), consisting of such factors as perinatal stress and low birth weight (Mick et al., 2002b), traumatic brain injury (Max et al., 1998), maternal smoking during pregnancy (Mick et al., 2002a), and severe early deprivation (Kreppner et al., 2001). In the latter case, the deprivation must be extreme, as often occurs in institutional rearing or child maltreatment; there is no evidence that ordinary variations in child-rearing practices contribute to the etiology of ADHD.

Neuroimaging is a valuable research tool in the study of ADHD, but it is not useful for making a diagnosis of ADHD in clinical practice or in predicting treatment response (Zametkin et al., 2005). Children with ADHD have reduced cortical white and gray matter volume relative to controls, although there is much overlap between the groups. Furthermore, such volume deficits are more pronounced in treatment-naïve children with ADHD than in those who have received long-term medication treatment (Castellanos et al., 2002). Sowell et al. (2003) also found decreased frontal and temporal lobe volume in children with ADHD relative to controls; gray matter deficits have also been found in the unaffected siblings of children with ADHD (Durston et al., 2004). Although the functional imaging of ADHD is in a preliminary stage, it has been shown that when patients with ADHD perform tasks requiring inhibitory control, differences in brain activation relative to controls have been found in the caudate, frontal lobes, and anterior cingulate (Bush et al., 2005).

RECENT ADVANCES IN TREATMENT

At the time of publication of the first AACAP practice parameter for ADHD in 1997 (American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 1997), the literature devoted to the treatment of ADHD was already voluminous. Stimulant treatment of ADHD was also the subject of an AACAP practice parameter (American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 2002). Most of that literature focused on the short-term treatment of ADHD, either with medication or psychosocial interventions. At the time of the first parameter, the intensive study of the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of stimulant medications was undertaken, pioneered by the group at the University of California at Irvine. Analog classroom settings were used to examine the hour-by-hour effects of stimulant medications on behavior and cognition and its relationship to serum stimulant medications (Swanson et al., 1998b, 2002b). Such studies lead to the development of Concerta (Swanson et al., 1999a, 1998b, 2000, 2002a, 2003), Adderall XR (Greenhill et al., 2003; McCracken et al., 2003), Metadate CD (Swanson et al., 2004; Wigal et al., 2003), and Focalin (Quinn et al., 2004).

Subsequently, numerous large-scale clinical trials prove the efficacy of these new agents (Biederman et al., 2002; Greenhill et al., 2002, 2005; McCracken et al., 2003; Pelham et al., 1999; Wigal et al., 2005; Wolraich, 2000; Wolraich et al., 2001) and atomoxetine (Michelson et al., 2001, 2003). A methylphenidate transdermal patch (Findling and Lopez, 2005; Pelham et al., 2005) has been recently approved for use. With these newer agents, efficacy has been established by rigorous, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter trials. Longer term, open-label studies of these agents, often lasting up to 2 years, have also been performed, giving the field more data about efficacy and safety after prolonged use.

The role of psychosocial interventions in the treatment of ADHD has also been much studied. The NIMH MTA study (MTA Cooperative Group, 1999a, 2004a) and the Multimodal Psychosocial Treatment study (M+MPT, also known as the New York/Montreal study; Klein et al., 2004) have examined the unitary and combined effects of pharmacological and behavioral treatments on ADHD symptoms and its associated impairments in social and academic functioning. The MTA study has completed naturalistic follow-ups of their patients up to 22 months after ending the active study treatment phase (Jensen, 2005; Swanson, 2005). These large-scale, long-term, randomized clinical trials have greatly informed the field as to the efficacy of long-term medication treatment and the role of psychosocial interventions in ADHD. In particular, answers to the question of when ADHD should be treated with pharmacological or behavioral therapy (or a combination of the two) can be based on empirical evidence.

EVIDENCE BASE FOR PRACTICE PARAMETERS

The AACAP develops both patient-oriented and clinician-oriented practice parameters. Patient-oriented parameters provide recommendations to guide clinicians toward the best treatment practices. Treatment recommendations are based both on empirical evidence and clinical consensus, and are graded according to the strength of the empirical and clinical support. Clinician-oriented parameters provide clinicians with the information (stated as principles) needed to develop practice-based skills. Although empirical evidence may be available to support certain principles, principles are primarily based on expert opinion and clinical experience.

In this parameter, recommendations for best treatment practices are stated in accordance with the strength of the underlying empirical and/or clinical support, as follows:

| •. | [MS] Minimal Standard is applied to recommendations that are based on rigorous empirical evidence (e.g., randomized, controlled trials) and/or overwhelming clinical consensus. Minimal standards apply more than 95% of the time (i.e., in almost all cases). | ||||

| •. | [CG] Clinical Guideline is applied to recommendations that are based on strong empirical evidence (e.g., nonrandomized, controlled trials) and/or strong clinical consensus. Clinical guidelines apply approximately 75% of the time (i.e., in most cases). | ||||

| •. | [OP] Option is applied to recommendations that are acceptable based on emerging empirical evidence (e.g., uncontrolled trials or case series/reports) or clinical opinion, but lack strong empirical evidence and/or strong clinical consensus. | ||||

| •. | [NE] Not Endorsed is applied to practices that are known to be ineffective or contraindicated. | ||||

The strength of the empirical evidence is rated in descending order as follows:

| •. | [rct] Randomized, controlled trial is applied to studies in which subjects are randomly assigned to two or more treatment conditions. | ||||

| •. | [ct] Controlled trial is applied to studies in which subjects are nonrandomly assigned to two or more treatment conditions. | ||||

| •. | [ut] Uncontrolled trial is applied to studies in which subjects are assigned to one treatment condition. | ||||

| •. | [cs] Case series/report is applied to a case series or a case report. | ||||

SCREENING

Recommendation 1. Screening for ADHD should be part of every patient's mental health assessment [MS].

In any mental health assessment, the clinician should screen for ADHD by specifically asking questions regarding the major symptom domains of ADHD (inattention, impulsivity, and hyperactivity) and asking whether such symptoms cause impairment. These screening questions should be asked regardless of the nature of the chief complaint. Rating scales or specific questionnaires containing the DSM symptoms of ADHD can also be included in clinic/office registration materials to be completed by parents before visits or in the waiting room before the evaluation. If a parent reports that the patient suffers from any symptoms of ADHD that induce impairment or if the patient scores in the clinical range for ADHD symptoms on a rating scale, then a full evaluation for ADHD as set out in the next recommendation is indicated.

EVALUATION

Recommendation 2. Evaluation of the preschooler, child, or adolescent for ADHD should consist of clinical interviews with the parent and patient, obtaining information about the patient's school or day care functioning, evaluation for comorbid psychiatric disorders, and review of the patient's medical, social, and family histories [MS].

The clinician should perform a detailed interview with the parent about each of the 18 ADHD symptoms listed in DSM-IV. For each symptom, the clinician should determine whether it is present as well as its duration, severity, and frequency. Age at onset of the symptoms should be assessed. The patient must have the required number of symptoms (at least six of nine of the inattention cluster and/or at least six of nine of the hyperactive/impulsive criteria, each occurring more days than not), a chronic course (symptoms do not remit for weeks or months at a time), and onset of symptoms during childhood. After all of the symptoms are assessed, the clinician should determine in which settings impairment occurs. Because most patients with ADHD have academic impairment, it is important to ask specific questions about this area. This is also an opportunity for the clinician to review the patient's academic/intellectual progress and look for symptoms of learning disorders (see Recommendation 4). Presence of impairment should be distinguished from presence of symptoms. For instance, a patient's ADHD symptoms may be observable only at school but not at home. Nonetheless, if the patient must spend an inordinate amount of time completing schoolwork in the evening that was not done in class, then impairment is present in two settings. DSM-IV requires impairment in at least two settings (home, school, or job) to meet criteria for the disorder, but clinical consensus agrees that severe impairment in one setting warrants treatment.

After reviewing the ADHD symptoms, the clinician should interview the parent regarding other common psychiatric disorders of childhood. In general, it is most logical to next gather data from the parent regarding ODD and CD. Then, the clinician should explore whether the patient has symptoms of depression (and associated neurovegetative signs), mania, anxiety disorders, tic disorders, substance abuse, and psychosis, or evidence of a learning disability. Other practice parameters of the AACAP contain specific recommendations on eliciting symptoms of these disorders in children and adolescents (see also Recommendation 5).

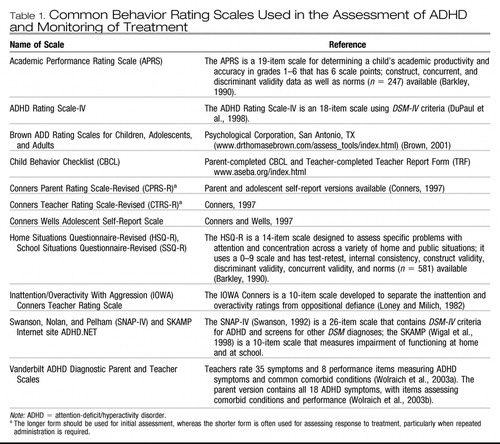

The parent should complete one of the many standardized behavior rating scales that have well-established normative values for children of a wide range of ages and genders. Scales in common use are listed in Table 1. These scales not only yield a measure of ADHD behaviors but also tap into other psychiatric symptoms that could be comorbid with ADHD or may suggest an alternative psychiatric diagnosis. It is advisable for the clinician to request a release of information from the parent to obtain a similar rating scale from the patient's teacher(s). It is important to note that such rating scales do not by themselves diagnose ADHD, although parent or teacher ratings of inattention or hyperactivity/impulsivity that fall in the upper fifth percentile for the patient's age and gender are reason for serious concern. If the teacher cannot provide such a rating scale or the parent declines permission to contact the school, then materials from school, such as work samples or report cards, should be reviewed or inquired about.

|

Table 1. Common Behavior Rating Scales Used in the Assessment of ADHD and Monitoring of Treatment

Family history and family functioning should be assessed. Because ADHD is highly heritable, a high prevalence of ADHD is likely to be found among the patient's parents and siblings. Family history of other significant mental disorders (affective, anxiety, tic, or CD) is helpful in determining the nature of any comorbid disorders, although a comorbid disorder should not be diagnosed solely on the basis of a family history of that comorbid disorder. Social history of the family should be examined. Because patients with ADHD perform better in structured settings, any factors in the family that create an inconsistent, disorganized environment may further impair the patient's functioning. Information regarding any physical or psychological trauma the patient may have experienced (including multiple visits to the emergency room) should be gathered as well as any current psychosocial stressors.

The clinician should obtain information about the patient's perinatal history, developmental milestones, medical history, and mental health history (especially any previous psychiatric treatment). Delays in reaching developmental milestones or in social/language development suggest language disorders, mental retardation, or pervasive developmental disorders. Assessment of developmental milestones is particularly important in the evaluation of the preschooler because many developmental disorders are associated with attention problems and hyperactivity.

The clinician should next interview the child or adolescent. For the preschool or young school-age child (5–8 years old), this interview may be done concurrently with the parent interview. Older children and adolescents should be interviewed separately from parents, as older children and teenagers may not reveal significant symptoms (depression, suicide, or drug or alcohol abuse) in the presence of a parent. Clinicians should be prepared to conduct a separate interview even with a younger child in many clinical situations, such as if the patient appears at risk of abuse or there is evidence of significant family dysfunction. The primary purpose of the interview with the child or adolescent is not to confirm or refute the diagnosis of ADHD. Young children are often unaware of their symptoms of ADHD, and older children and adolescents may be aware of symptoms but will minimize their significance. The interview with the child or adolescent allows the clinician to identify signs or symptoms inconsistent with ADHD or suggestive of other serious comorbid disorders. The clinician should perform a mental status examination, assessing appearance, sensorium, mood, affect, and thought processes. Through the interview process, the clinician develops a sense of whether the patient's vocabulary, thought processes, and content of thought are age-appropriate. Marked disturbances in mood, affect, sensorium, or thought process suggest the presence of psychiatric disorders other than or in addition to ADHD.

Recommendation 3. If the patient's medical history is unremarkable, laboratory or neurological testing is not indicated [NE].

There are few medical conditions that “masquerade” as ADHD, and the vast majority of patients with ADHD will have an unremarkable medical history. Children suffering a severe head injury may develop symptoms of ADHD, usually of the inattentive subtype. Encephalopathies generally produce other neurological symptoms (language or motor impairment) in addition to inattention. Hyperthyroidism, which can be associated with hyperactivity and agitation, rarely presents with ADHD symptoms alone but with other signs and symptoms of excessive thyroid hormone levels. The measurement of thyroid levels and thyroid-stimulating hormone should be considered only if symptoms of hyperthyroidism other than increased activity level are present. Exposure to lead, either prenatally or during development, is associated with a number of neurocognitive impairments, including ADHD (Lidsky and Schneider, 2003). If a patient has been raised in an older, innercity environment where exposure to lead paint or plumbing is probable, then serum lead levels should be considered. Serum lead level should not be part of routine screening. Children with fetal alcohol syndrome or children exposed in utero to other toxic agents have a higher incidence of ADHD than the general population (O'Malley and Nanson, 2002).

Unless there is strong evidence of such factors in the medical history, neurological studies (electroencephalography [EEG], magnetic resonance imaging, singlephoton emission computed tomography [SPECT], or positron emission tomography [PET]) are not indicated for the evaluation of ADHD. Specifically, the Council on Children, Adolescents, and Their Families of the American Psychiatric Association has warned against the exposure of children to intravenous radioactive nucleotides as part of the diagnosis or treatment of childhood psychiatric disorders, citing both a lack of evidence of validity and safety issues (http://www.psych.org/psych_pract/clin_issues/populations/children/SPECT.pdf).

Recommendation 4. Psychological and neuropsychological tests are not mandatory for the diagnosis for ADHD, but should be performed if the patient's history suggests low general cognitive ability or low achievement in language or mathematics relative to the patient's intellectual ability [OP].

Low scores on standardized testing of academic achievement frequently characterize ADHD patients (Tannock, 2002). The clinician must determine whether the academic impairment is secondary to the ADHD, if the patient has ADHD and a learning disorder, or if the patient has only a learning disorder and the patient's inattentiveness is secondary to the learning disorder. Academic impairment is commonly due to the ADHD itself. Many months or years of not listening in class, not mastering material in an organized fashion, and not practicing academic skills (not doing homework, etc.) leads to a decline in achievement relative to the patient's intellectual ability. If the parent and teacher report that the patient performs at (or even above) grade level on subjects when given one-to-one supervision (a patient can do all of the problems on a test when held in from recess), then a formal learning disorder is less likely. In some cases, the patient may engage in leisure activities that require the skill (e.g., reading science fiction novels) but avoid reading a history book in preparation for an exam. In such cases, it is more appropriate to treat the ADHD and then determine whether the academic problems begin to resolve as the patient is more attentive in learning situations. However, if there is no clear evidence of an improvement in academic performance in 1 to 2 months despite improvement of the ADHD, then psychological testing for learning disorders is indicated.

In other cases, symptoms of learning/language disorders are present that cannot be accounted for by ADHD. These include deficits in expressive and receptive language, poor phonological processing, poor motor coordination, or difficulty grasping fundamental mathematical concepts. In such cases, psychological testing will be needed to identify whether these deficits are related to a specific learning disorder. In the vast majority of cases, these learning disorders will be comorbid with the ADHD, and it is recommended strongly that the patient's ADHD be optimally treated before such testing. It could then be firmly concluded that any deficits identified are clearly the result of a learning disorder and not due to inattention to the test materials.

Purely learning-disordered patients are often inattentive when struggling with material in the area of their disability (a reading-disordered patient is inattentive when he or she must read) but do not have problems outside such a restricted academic setting. Patients with learning disorders alone do not show symptoms of impulsivity or hyperactivity. Children and adolescents with learning disorders may be oppositional with regard to schoolwork, and the clinician is consulted as to whether ADHD is the cause of the oppositional behavior. If a careful interview shows the absence of full criteria for ADHD and if the emergence of the oppositional behavior is clearly correlated with academic demands, then a primary learning disorder is more likely.

Psychological testing of the ADHD patient usually consists of a standardized assessment of intellectual ability (IQ) to determine any contribution of low general cognitive ability to the academic impairment, and academic achievement. Neuropsychological testing, speech-language assessments, and computerized testing of attention or inhibitory control are not required as part of a routine assessment for ADHD, but may be indicated by the findings of the standard psychological assessment.

Recommendation 5. The clinician must evaluate the patient with ADHD for the presence of comorbid psychiatric disorders [MS].

The clinician must integrate the data obtained with regard to comorbid symptoms to determine whether the patient meets criteria for a separate comorbid disorder in addition to ADHD, the comorbid disorder is the primary disorder and the patient's inattention or hyperactivity/impulsivity is directly caused by it, or the comorbid symptoms do not meet criteria for a separate disorder but represent secondary symptoms stemming from the ADHD.

When patients with ADHD meet full DSM-IV criteria for a second disorder, the clinician should generally assume the patient has two or more disorders and develop a treatment plan to address each comorbid disorder in addition to the ADHD. Children with ADHD commonly meet criteria for ODD or CD. In young children these disorders are nearly always present concurrently. Similarly, if a patient meets full DSM-IV criteria for major depressive disorder or a specific anxiety disorder, the clinician is most likely dealing with a comorbid disorder. Most often, the onset of the depressive disorder occurs several years after the onset of ADHD (Spencer et al., 1999), whereas anxiety disorders have an earlier onset concurrent with the ADHD (Kovacs and Devlin, 1998). A comorbid diagnosis of mania should be considered in ADHD patients who exhibit severe mood lability/elation/irritability, thought disturbances (grandiosity, flight of ideas), severe aggressive outbursts (“affective storms”), and decreased need for sleep or age-inappropriate levels of sexual interest. Mania should not be diagnosed solely on the basis of the severity of the ADHD symptoms or aggressive behavior in the absence of the manic symptoms listed above. Acutely manic ADHD patients generally require mood stabilization before treatment of the ADHD. The choice of a treatment regimen, particularly pharmacological intervention, is often influenced by the nature of the patient's comorbid disorder and which disorder is currently the most impairing of major life activities. Older adolescents with ADHD should be screened for substance abuse disorders, as they are at greater risk than teenagers without ADHD for smoking and alcohol and other illegal substance abuse disorders (Biederman et al., 1997; Wilens et al., 1997).

In other cases, another primary psychiatric disorder produces impairment of attention or impulse control. Impaired attention is caused by primary depressive/anxiety disorders, and those with primary mania have impaired impulse control and judgment. If a patient has no history of ADHD symptoms during childhood but develops inattentiveness and poor concentration only after the onset of depression or mania, then the affective disorder is most likely primary. Patients with adolescent-onset ODD or CD are often described as impulsive or inattentive, but often do not meet full criteria for ADHD or had few ADHD symptoms in early childhood.

Finally, some associated problems may stem from the ADHD itself and not be a separate disorder. Patients with ADHD may develop associated symptoms of dysphoria or low self-esteem secondary to the frustrations of living with ADHD. In such cases, the dysphoria is related specifically to the ADHD symptoms and there is an absence of pervasive depression, neurovegetative signs, or suicidal ideation. If such dysphoria is a result of the ADHD, then it should respond to successful treatment of the ADHD. The distractibility or impulsivity of ADHD patients may often be interpreted as oppositional behavior by caretakers or children. Mild mood lability (shouting out, crying easily, quick temper) is also common in ADHD. It is important to note that such associated symptoms do not reach the level of a separate DSM disorder; are temporally related to the onset of the ADHD; are often consistent with, although somewhat excessive, for the social context; and dissipate once the ADHD is successfully treated.

TREATMENT

Recommendation 6. A well-thought-out and comprehensive treatment plan should be developed for the patient with ADHD [MS].

The patient's treatment plan should take account of ADHD as a chronic disorder and may consist of psychopharmacological and/or behavior therapy. This plan should take into account the most recent evidence concerning effective therapies as well as family preferences and concerns. This plan should include parental and child psychoeducation about ADHD and its various treatment options (medication and behavior therapy), linkage with community supports, and additional school resources as appropriate. Psychoeducation is distinguished from psychosocial interventions such as behavior therapy. Psychoeducation is generally performed by the physician in the context of medication management and involves educating the parent and child about ADHD, helping parents anticipate developmental challenges that are difficult for ADHD children, and providing general advice to the parent and child to help improve the child's academic and behavioral functioning. The treatment plan should be reviewed regularly and modified if the patient's symptoms do not respond. Trade books, videos, and some noncommercial Web sites on ADHD may be useful adjunctive material to facilitate this step of treatment.

The short-term efficacy of psychopharmacological intervention for ADHD was well established at the time of the first AACAP practice parameter for ADHD (American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 1997). It is also clear that behavior therapy alone can produce improvement in ADHD symptoms relative to baseline symptoms or to wait-list controls (Pelham et al., 1998). Since then, a substantial focus has been on the relative efficacy of pharmacological therapy versus psychosocial intervention. Jadad et al. (1999) reviewed 78 studies of the treatment of ADHD; six of these studies compared pharmacological and nonpharmacological interventions. The reviewers reported that studies consistently supported the superiority of stimulant over the nondrug treatment. Twenty studies compared combination therapy with a stimulant or with psychosocial intervention, but no evidence of an additive benefit of combination therapy was found. Most of these studies involved short-term behavioral treatment; a major hypothesis in the early 1990s was that behavior therapy had to be administered for an extended time for patients with ADHD to realize its full benefit (Richters et al., 1995). Thus, the MTA study was designed to look at comprehensive treatments provided over an entire year.

In the MTA study, children with ADHD were randomized to four groups: algorithmic medication treatment alone, psychosocial treatment alone, a combination of algorithmic medication management and psychosocial treatment, and community treatment. Algorithmic medication treatment consisted of monthly appointments in which the dose of medication was carefully titrated according to parent and teacher rating scales. Children in all four treatment groups showed reduced symptoms of ADHD at 14 months relative to baseline. The two groups that received algorithmic medication management showed a superior outcome with regard to ADHD symptoms compared with those that received intensive behavioral treatment alone or community treatment (MTA Cooperative Group, 1999a [rct]). Those who received behavioral treatment alone were not significantly more improved than the group of community controls who received community treatment (two thirds of the subjects in this group received stimulant treatment). The community treatment group had more limited physician follow-up and was treated with lower daily doses of stimulant compared with the algorithmic medication management group. Nearly one fourth of the subjects randomized to receive behavioral treatment alone required treatment with medication during the trial because of a lack of effectiveness of the behavioral treatment. It seems established that a pharmacological intervention for ADHD is more effective than a behavioral treatment alone.

This does not mean, however, that behavior therapy alone cannot be pursued for the treatment of ADHD in certain clinical situations. Behavior therapy may be recommended as an initial treatment if the patient's ADHD symptoms are mild with minimal impairment, the diagnosis of ADHD is uncertain, parents reject medication treatment, or there is marked disagreement about the diagnosis between parents or between parents and teachers. Preference of the family should also be taken into account. A number of behavioral programs for the treatment of ADHD have been developed. Since the review by Pelham et al. (1998), a number of other controlled studies have shown short-term effectiveness of behavioral parent training (Chronis et al., 2004; Sonuga-Barke et al., 2001 [rct], 2002 [rct]). Several manual-based treatments for applying behavioral parent training to ADHD and ODD children are available (Barkley, 1997; Cunningham et al., 1997). Smith et al. (2006) provided an overview of the principles behind such programs. In general, parents are involved in 10 to 20 sessions of 1 to 2 hours in which they (1) are given information about the nature of ADHD, (2) learn to attend more carefully to their child's misbehavior and to when their child complies, (3) establish a home token economy, (4) use time out effectively, (5) manage noncompliant behaviors in public settings, (6) use a daily school report card, and (7) anticipate future misconduct. Occasional booster sessions are often recommended. Parental ADHD may interfere with the success of such programs (Sonuga-Barke et al., 2002), suggesting that treatment of an affected parent maybe an important part of the child's treatment. Generalized family dysfunction (parental depression, substance abuse, marital problems) may also need to be addressed so that psychosocial or medication treatment is fully effective for the child with ADHD (Chronis et al., 2004).

The 1997 practice parameter (American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 1997) extensively reviewed a variety of nonpharmacological interventions for ADHD other than behavior therapy, including cognitive-behavioral therapy and dietary modification. No evidence was found at that time to support these interventions in patients with ADHD, and no studies have appeared since then that would justify their use. Although there has been aggressive marketing of its use, the efficacy of EEG feedback, either as a primary treatment for ADHD or as an adjunct to medication treatment, has not been established (Loo, 2003). Formal social skills training for children with ADHD has not been shown to be effective (Antshel and Remer, 2003).

Recommendation 7. The initial psychopharmacological treatment of ADHD should be a trial with an agent approved by the food and drug administration for the treatment of ADHD [MS].

The following medications are approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of ADHD: dextroamphetamine (DEX), d- and d,l-methylphenidate (MPH), mixed salts amphetamine, and atomoxetine.

STIMULANTS

Many randomized clinical trials of stimulant medications have been performed in patients with ADHD during the past 3 decades. Stimulants are highly efficacious in the treatment of ADHD. In double-blind, placebo-controlled trials in both children and adults, 65% to 75% of subjects with ADHD have been determined to be clinical responders to stimulants compared with 4% to 30% of subjects treated with placebo, depending on the response criteria used (Greenhill, 2002). When clinical response is assessed quantitatively via rating scales, the effect size of stimulant treatment relative to placebo is rather large, averaging about 1.0, one of the largest effects for any psychotropic medication. In the MTA study, subjects who responded to short-term placebo treatment did not maintain such gains and 90% of these subjects were subsequently treated with stimulants in the 14-month time frame of the study (Vitiello et al., 2001).

The physician is free to choose any of the two stimulant types (MPH or amphetamine) because evidence suggests the two are equally efficacious in the treatment of ADHD. Immediate-release stimulant medications have the disadvantage that they must be taken two to three times per day to control ADHD symptoms throughout the day. In the past 5 years, extensive trials have been carried out with long-acting forms of MPH (Concerta, Daytrana, Focalin-XR, Metadate, Ritalin LA), mixed salts amphetamine (Adderall XR), and an amphetamine prodrug lisdex-amfetamine (Vyvanse; Biederman et al., 2002, 2006; Findling and Lopez, 2005; Greenhill et al., 2002, 2006b; McGough et al., 2006b; Wolraich et al., 2001). These long-acting formulations are equally efficacious as the immediate-release forms and have been shown to be efficacious in adolescents as well as children (Spencer et al., 2006; Wilens et al., 2006). They offer greater convenience for the patient and family and enhance confidentiality because the school-age patient need not report to the school nurse for medication administration. Single daily dosing is associated with greater compliance for all types of medication, and long-acting MPH may improve driving performance in adolescents relative to short-acting MPH (Cox et al., 2004 [rct]). Physicians may use long-acting forms as initial treatment; there is no need to titrate to the appropriate dose on short-acting forms and then “transfer” children to a long-acting form. Short-acting stimulants are often used as initial treatment in small children (<16 kg in weight), for whom there are no long-acting forms in a sufficiently low dose.

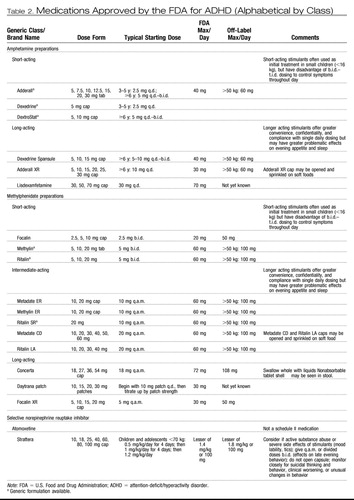

Typical dosing of the stimulant medications is shown in Table 2. The AACAP has also issued specific parameters for the use of stimulant medications (American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 2002). These doses represent guidelines; with careful clinical monitoring, these doses may be exceeded in individual cases. Studies of the treatment of adult ADHD shed light on the doses necessary to optimally treat adult-sized adolescents. Spencer et al. (2005 [rct]) conducted a 6-week double-blind, parallel-group study of MPH in 146 adults with ADHD. MPH was highly efficacious (76% response rate on MPH versus 19% on placebo) at a mean oral dose of 1.1 mg/kg/day (mean daily dose 88 ± 22 mg). This would suggest that adult-sized adolescents may need doses of MPH in this range (or the equivalent dose in amphetamine or Concerta) to achieve an adequate response, but careful monitoring for side effects should be undertaken at such doses. There have not been any studies examining the effects of doses of MPH or amphetamine in adolescents of more than 60 mg/day or 72 mg of Concerta. Doses in this range should be used only with caution, with frequent monitoring of side effects. On average, there is a linear relationship between dose and clinical response: that is, in any group of ADHD subjects, more subjects will be classified as responders and there is a greater reduction in symptoms at the higher doses of stimulant. There is no evidence of a global “therapeutic” window in ADHD patients. Each patient, however, has a unique dose-response curve. If a full range of MPH doses are used, then roughly a third of school-age patients will have an initial optimal response on a low (<15 mg/day), a medium (16–34 mg/day), or a high (>34 mg/day) daily dose (Vitiello et al., 2001 [rct]). Most, however, will require dose adjustment upward as treatment progresses.

|

Table 2. Medications Approved by the FDA for ADHD (Alphabetical by Class)

After selecting the starting dose, the physician may titrate upward every 1 to 3 weeks until the maximum dose for the stimulant is reached, symptoms of ADHD remit, or side effects prevent further titration, whichever occurs first. Contact with physician or trained office staff during titrations is recommended. It is helpful to obtain teacher and parent rating scales after the patient has been observed by the adult on a selected dose for at least 1 week. The parent and the patient should be queried about side effects. An office visit should then be scheduled after the first month of treatment to review overall progress and determine whether the stimulant trial was a success and long-term maintenance on the particular stimulant should commence.

Arnold (2000) reviewed studies in which subjects underwent a trial of both amphetamine and MPH. This review suggested that approximately 41% of subjects with ADHD responded equally to both MPH and amphetamine, whereas 44% responded preferentially to one of the classes of stimulants. This suggests the initial response rate to stimulants may be as high as 85% if both stimulants are tried (in contrast to the finding of 65%–75% response when only one stimulant is tried). There is at present, however, no method to predict which stimulant will produce the best response in a given patient. The titration schedule for DEX or mixed salts amphetamine follows a similar practice as for MPH. Patients with ADHD and comorbid anxiety or disruptive behavior disorders have as robust a response of their ADHD symptoms to stimulants as do patients who do not have these comorbid conditions (MTA Cooperative Group, 1999b [rct]).

TREATMENT OF PRESCHOOLERS WITH STIMULANTS

Stimulants have been widely prescribed by clinicians for this age group, although the number of published controlled trials is limited. Connor (2002) reviewed nine small studies of MPH in children younger than 6 years old, all of which used some type of blind as well as a crossover or parallel-group design. These studies involved 206 subjects and used doses of MPH that ranged from 2.5 to 30 mg/day or 0.15 to 1.0 mg/kg/day. Eight of the nine studies supported the efficacy of MPH in the treatment of preschoolers with ADHD at milligram-per-kilogram doses that were comparable with those used in school-age children. Studies of preschoolers with significant developmental delays suggested this subgroup was prone to higher rates of side effects including social withdrawal, irritability, and crying (Handen et al., 1999 [rct]). Thus, a cautious titration is recommended in this subgroup. In the NIMH-funded Preschool ADHD Treatment Study (PATS), 183 children ages 3 to 5 years underwent an open-label trial of MPH; subsequently, 165 of these subjects were randomized into a double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover trial of MPH lasting 6 weeks (Kollins et al., 2006). The 140 subjects who completed this second phase went on to enter a long-term maintenance study of MPH. Parents of subjects in this study were required to complete a 10-week course of parent training before their child was treated with medication. Of note, only 37 of 279 enrolled parents thought that the behavior training resulted in significant or satisfactory improvement (Greenhill et al., 2006a).

Results from the short-term, open-label, run-in and double-blind, crossover studies do show that MPH is effective in preschoolers with ADHD (Greenhill et al., 2006a). The mean optimal dose of MPH was found to be 0.7 ± 0.4 mg/kg/day, which is lower than the mean of 1.0 mg/kg/day found to be optimal in the MTA study with school-age children. Eleven percent of subjects discontinued MPH because of adverse events (Wigal et al., 2006). Also relative to the MTA study, the preschool group showed a higher rate of emotional adverse events, including crabbiness, irritability, and proneness to crying. The conclusion was that the dose of MPH (or any stimulant) should be titrated more conservatively in preschoolers than in school-age patients, and lower mean doses may be effective. A pharmacokinetic study done as part of the PATS protocol showed that preschoolers metabolized MPH more slowly than did school-age children, perhaps explaining these results (McGough et al., 2006a).

ATOMOXETINE

Atomoxetine is a noradrenergic reuptake inhibitor that is superior to placebo in the treatment of ADHD in children, adolescents, and adults (Michelson et al., 2001 [rct], 2002 [rct], 2003 [rct]; Swensen et al., 2001 [rct]). Its effect size was calculated to be 0.7 in one study (Michelson et al., 2002). Atomoxetine can be given once or twice daily, with the second dose given in the evening; atomoxetine may have less pronounced effects on appetite and sleep than stimulants, although they may produce relatively more nausea or sedation. Dosing of atomoxetine is shown in Table 2.

Michelson et al. (2002) showed that although atomoxetine was superior to placebo at week 1 of the trial, the greatest effects were observed at week 6, suggesting the patient should be maintained at the full therapeutic dose for at least several weeks to obtain the drug's full effect. Atomoxetine has been studied in the treatment of patients with ADHD and comorbid anxiety (Sumner et al., 2005 [rct]). Patients with ADHD or an anxiety disorder (generalized anxiety, separation anxiety, or social phobia) were randomized to either atomoxetine (n = 87) or placebo (n = 89) in a double-blind, placebo-controlled manner for 12 weeks of treatment. At the end of the treatment period, atomoxetine led to a significant reduction in ratings of symptoms of both ADHD and anxiety relative to placebo, showing the drug to be efficacious in the treatment of both conditions. This study is of interest because treatment algorithms for ADHD with comorbid anxiety have recommended treatment of ADHD first with stimulants, then addition of a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) for treatment of the anxiety (Pliszka et al., 2000). Recently, however, the SSRI fluvoxamine was shown not to be superior to placebo for the treatment of anxiety when added to a stimulant in a small sample (n = 25) of children with ADHD and comorbid anxiety (Abikoff et al., 2005 [rct]). This small study does not invalidate this practice, but the above results of Sumner et al. (2005) suggest that using atomoxetine for the treatment of ADHD with comorbid anxiety is a viable alternative approach. No evidence exists that atomoxetine is effective for the treatment of major depressive disorder, however.

SELECTION OF AGENT

The clinician and family face the choice of which agent to use for the initial treatment of the patient with ADHD. The American Academy of Pediatrics (2001), an international consensus statement (Kutcher et al., 2004), and the Texas Children's Medication Project (Pliszka et al., 2006a) have recommended stimulants as the first line of treatment for ADHD, particularly when no comorbidity is present. Direct comparisons of the efficacy of atomoxetine with that of MPH (Michelson, 2004) and amphetamine (Wigal et al., 2004) have shown a greater treatment effect of the stimulants, and in a meta-analysis of atomoxetine and stimulant studies, the effect size for atomoxetine was 0.62 compared with 0.91 and 0.95 for immediate-release and long-acting stimulants, respectively (Faraone et al., 2003). However, atomoxetine may be considered as the first medication for ADHD in individuals with an active substance abuse problem, comorbid anxiety, or tics. Atomoxetine is preferred if the patient experiences severe side effects to stimulants such as mood lability or tics (Biederman et al., 2004). When dosed twice daily, effects on late evening behavior may be seen.

It is the sole choice of the family and the clinician as to which agent should be used for the patient's treatment, and each patient's treatment must be individualized. Nothing in these guidelines should be construed by third-party payers as justification for requiring a patient to be a treatment failure (or experience side effects) to one agent before allowing the trial of another.

Recommendation 8. If none of the above agents result in satisfactory treatment of the patient with ADHD, the clinician should undertake a careful review of the diagnosis and then consider behavior therapy and/or the use of medications not approved by the FDA for the treatment of ADHD [CG].

The vast majority of patients with ADHD who do not have significant comorbidity respond satisfactorily to the agents listed in Recommendation 7. If a patient fails to respond to trials of all of these agents after an adequate length of time at appropriate doses for the agent as noted in Table 2, then the clinician should undertake a review of the patient's diagnosis of ADHD. This does not require the patient to be completely reevaluated, but the clinician should be certain of the accuracy of the history that led to the diagnosis of ADHD and examine whether any undetected comorbid conditions are present, such as affective disorders, anxiety disorders, or subtle developmental disorders. The clinician should ascertain that these factors are not the primary problems impairing the patient's attention and impulse control. Primary care physicians should consider referral to a child and adolescent psychiatrist at this point.

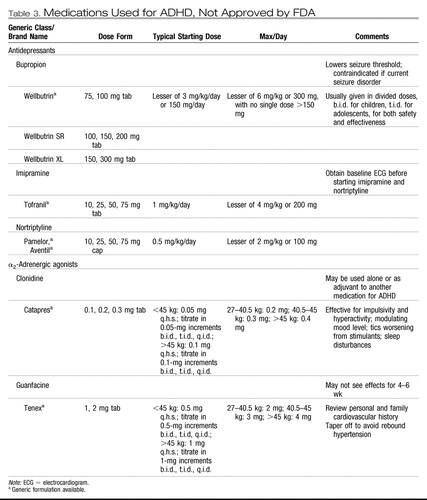

Bupropion, tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), and α-agonists are often used in the treatment of ADHD even though they are not approved by the FDA for this purpose. Although there is at least one double-blind, randomized, controlled trial for bupropion, TCAs, and clonidine, the evidence base for these medications is far weaker than for the FDA-approved agents (Pliszka, 2003). Their doses for clinical use are shown in Table 3. These agents may have effect sizes considerably less than those of the approved agents and comparable with the effectiveness of behavior therapy (Pelham et al., 1998). Thus, it may be prudent for the clinician to recommend a trial of behavior therapy at this point, before moving to these second-line agents. In other cases, the patient may have had a partial response to one of the FDA-approved agents, wherein there is definite improvement over baseline symptoms but impairment at home or school still is present. As noted in Recommendation 12, addition of behavior therapy along with treatment with the FDA-approved agent may provide added benefit in such cases.

|

Table 3. Medications Used for ADHD, Not Approved by FDA

Bupropion, TCAs, and α-agonists, although not as extensively studied as the previously discussed medications, have shown effectiveness in small controlled trials or open trials. The common doses of these agents used in children and adolescents are shown in Table 3. Bupropion is a noradrenergic antidepressant that showed modest efficacy in the treatment of ADHD in one double-blind, placebo-controlled trial (Conners et al., 1996 [rct]). It is contraindicated in patients with a current seizure disorder. It can be given in either immediate-release or long-acting form, but may not come in pill sizes small enough for children who weigh <25 kg.

TCA medications are the most studied of the non-FDA-approved medications for the treatment of ADHD (Daly and Wilens, 1998 [rct]). Imipramine and nortriptyline have been most commonly used in recent years by clinicians. Among the TCAs, desipramine should be used with extreme caution in children and adolescents because there have been reports of sudden death (Biederman et al., 1995; Riddle et al., 1993). Desipramine should be used only if other TCAs have not proven effective or have caused the patient to suffer excessive side effects. For TCAs electrocardiography must be performed at baseline and after each dose increase. Once the patient is on a stable dose of the TCA, a plasma level should be obtained to ensure the level is not in the toxic range. However, if the level is subtherapeutic in terms of the range for the treatment of depression, there is no need to further increase the dose if the symptoms of ADHD are adequately controlled.

α-Agonists (clonidine and guanfacine) have been widely prescribed for patients with ADHD, for the disorder itself, for comorbid aggression, or to combat side effects of tics or insomnia. Extensive controlled trials of these agents are lacking. Connor et al. (1999) performed a meta-analysis of 11 studies of clonidine in the treatment of ADHD. The studies were highly variable in both method and outcome, and open-label studies showed a larger effect than controlled studies. Nevertheless, the review suggested a small to moderate effect size for clonidine in the treatment of ADHD. One small double-blind trial showed the superiority of guanfacine over placebo in the treatment of children with ADHD and comorbid tics (Scahill et al., 2001 [rct]). A gradual titration is required and clinical consensus suggests the α-agonists are more successful in treating hyperactive/impulsive symptoms than inattention symptoms, although this remains to be proven by clinical trials. In recent years clinical consensus has led to the use of clonidine as adjunctive therapy to treat tics or stimulant-induced insomnia rather than as a primary treatment for ADHD. If the α-agonist is deemed ineffective after an adequate trial, the medication should be tapered gradually over 1 to 2 weeks to avoid a sudden increase in blood pressure.

Recommendation 9. During a psychopharmacological intervention for ADHD, the patient should be monitored for treatment-emergent side effects [MS].

For stimulant medications, the most common side effects are appetite decrease, weight loss, insomnia, or headache. Less common side effects of stimulants include tics and emotional lability/irritability. Treating physicians should be familiar with the precautions and reported adverse events contained in product labeling. Strategies for dealing with side effects include monitoring, dose adjustment of the stimulant, switching to another stimulant, and adjunctive pharmacotherapy to treat the side effects. If one of these side effects emerges, then the physician should first assess the severity of the symptom and the burden it imposes on the patient. It is prudent to monitor side effects that do not compromise the patient's health or cause discomfort that interferes with functioning because many side effects of stimulants are transient in nature and may resolve without treatment. This approach is particularly valuable if the patient has had a robust behavioral response to the particular stimulant medication. If the side effect persists, then reduction of dose should be considered, although the physician may find that the dose that does not produce the side effect is not effective in the treatment of the ADHD. In this case the physician should initiate a trial of a different stimulant or a nonstimulant medication.

After such trials, the physician, family, and patient may find that the one particular stimulant that is most efficacious in the treatment of that patient's ADHD also produces a troublesome side effect. In this case adjunctive pharmacotherapy may be considered. Low doses of clonidine, trazodone, or an antihistamine are often helpful for stimulant-induced insomnia. Clinicians must be aware of the risk of priapism in males treated with trazodone (James and Mendelson, 2004). Some patients become paradoxically excited when treated with antihistamines; anticholinergic effects of some antihistamine agents can be detrimental. Melatonin in doses of 3 mg has recently been shown to be helpful in improving sleep in children with ADHD treated with stimulants (Tjon Pian Gi et al., 2003 [ut]). A chart review suggested cyproheptadine can attenuate stimulant-induced anorexia (Daviss and Scott, 2004 [cs]).

How often stimulants induce tics in patients with ADHD is less clear. Recent double-blind clinical trials of both immediate-release and long-acting stimulants have not found that stimulants increase the rate of tics relative to placebo (Biederman et al., 2002 [rct]; Wolraich et al., 2001 [rct]). Children with comorbid ADHD and tic disorders, on average, show a decline in tics when treated with a stimulant. This remains true even after more than 1 year of treatment (Gadow et al., 1999 [ut]; Gadow and Sverd, 1990). If a patient has treatment-emergent tics during a trial of a given stimulant, then an alternative stimulant or a nonstimulant should be tried. If the patient's ADHD symptoms respond adequately only to a stimulant medication that induces tics, then combined pharmacotherapy of the stimulant and an α-agonist (clonidine or guanfacine) is recommended (Tourette's Syndrome Study Group, 2002 [rct]).

Side effects of atomoxetine that occurred more often than those with placebo include gastrointestinal distress, sedation, and decreased appetite. These can generally be managed by dose adjustment, and although some attenuate with time, others such as headaches may persist (Greenhill et al., 2007). If discomfort persists, then the atomoxetine should be tapered off, and a trial of a different medication initiated. On December 17, 2004, the FDA required a warning be added to atomoxetine because of reports that two patients (an adult and child) developed severe liver disease (both patients recovered). In the clinical trials of 6,000 patients, no evidence of hepatotoxicity was found. Patients who develop jaundice, dark urine, or other symptoms of hepatic disease should discontinue atomoxetine. Routine monitoring of hepatic function is not required during atomoxetine treatment.

AGGRESSION, MOOD LABILITY, AND SUICIDAL IDEATION

Controlled trials of stimulants do not support the widespread belief that stimulant medications induce aggression. Indeed, overall aggressive acts and antisocial behavior decline when ADHD patients are treated with stimulants (Connor et al., 2002 [rct]). A rate of emotional lability of 8.6% was reported in patients taking Adderall XR compared with a rate of 1.9% in the placebo group (Biederman et al., 2002). It should be noted, however, that this 4-week trial used an aggressive titration schedule, and children were randomized to dose condition regardless of weight. The physician must distinguish between aggression/emotional lability that is present when the stimulant is active (i.e., during the day) and increased hyperactivity/impulsivity in the evening when the stimulant is no longer effective. The latter phenomenon (commonly referred to as “rebound”) is more prevalent than the former, and it has been shown in laboratory classroom settings that even on placebo, the behavior of children with ADHD is worse in the late afternoon and evening than in the morning (Swanson et al., 1998a [rct]). Thus, the “worsening” behavior observed by the caretaker in the evening was probably present before treatment, but is more noticeable compared with the now improved behavior during the day. The physician may deal with this situation by administering a dose of immediate-release stimulant in the late afternoon. Such a dose is usually smaller than one of the morning doses.

The FDA and its Pediatric Advisory Committee have reviewed data regarding psychiatric adverse events to medications for the treatment of ADHD (U.S. Food and Drug Administration, 2006). Data from both controlled trials and postmarketing safety data from sponsors and the FDA Adverse Events Reporting System, also referred to as MedWatch, was reviewed. For most of the agents, these events were slightly more common in the active drug group relative to placebo in the controlled trials, but with the exception of suicidal thinking with atomoxetine (see below) and modafinil, these differences did not reach statistical significance (Mosholder, 2006). Postmarketing safety data were also reviewed for reports of mania/psychotic symptoms, aggression, and suicidality (Gelperin, 2006). Such reports have many limitations because information about dose, comorbid diagnoses, and concomitant medications is often not available. Nonetheless, for each agent examined (all stimulants, atomoxetine, and modafinil), there were reports of rare events of toxic psychotic symptoms, specifically involving visual and tactile hallucinations of insects. Symptoms of aggression and suicidality (but no completed suicides) were also reported. At the time, the Pediatric Advisory Committee did not recommend a boxed warning regarding psychiatric adverse events, but did suggest clarifying labeling regarding these phenomena. No changes to the stimulant medication labeling were suggested regarding suicide or suicidal ideation.

In September 2005 the FDA also issued an alert regarding suicidal thinking with atomoxetine in children and adolescents (U.S. Food and Drug Administration, 2005). In 12 controlled trials involving 1,357 patients taking atomoxetine and 851 taking placebo, the average risk of suicidal thinking was 4/1,000 in the atomoxetine-treated group versus none in those taking placebo. There was one suicide attempt in the atomoxetine group but no completed suicides. A boxed warning was added to the atomoxetine labeling. This risk is small, but it should be discussed with patients and family, and children should be monitored for the onset of suicidal thinking, particularly in the first few months of treatment.

If after starting an ADHD medication the patient clearly is more aggressive or emotionally labile or experiences psychotic symptoms, then the physician should discontinue that medication and consider a different agent. Adjunctive therapy with neuroleptics or mood stabilizers is not recommended if the aggressive/labile behavior was not present at baseline and is clearly a side effect of the stimulant.

CARDIOVASCULAR ISSUES

In March 2006 the Pediatric Advisory Committee also addressed the risk of sudden death occurring with agents used for the treatment of ADHD (Villalaba, 2006). The FDA review of events related to sudden death revealed 20 sudden death cases with amphetamine or dextroamphetamine (14 children, 6 adults), whereas there were 14 pediatric and four adults cases of sudden death with MPH. It is important to note that the rate of sudden death in the general pediatric population has been estimated at 1.3–8.5/100,000 patient-years (Liberthson, 1996). The rate of sudden death among those with a history of congenital heart disease can be as high as 6% by age 20 (Liberthson, 1996). Villalaba (2006) estimated the rate of sudden death in treated children with ADHD for the exposure period January 1, 1992 to December 31, 2004 to be 0.2/100,000 patient-years for MPH, 0.3/100,000 patient-years for amphetamine, and 0.5/100,000 patient-years for atomoxetine (the differences between the agents are not clinically meaningful). Thus, the rate of sudden death of children taking ADHD medications do not appear to exceed the base rate of sudden death in the general population. Although an advisory committee 1 month earlier had recommended a boxed warning be issued for cardiovascular events, including stroke and myocardial infarction (Nissen, 2006), the Pediatric Advisory Committee did not support this recommendation. No evidence currently indicates a need for routine cardiac evaluation (i.e., electrocardiography, echocardiography) before starting any stimulant treatment in otherwise healthy individuals (Biederman et al., 2006). The package insert for stimulants states that these medications should generally not be used in children and adolescents with preexisting heart disease or symptoms suggesting significant cardiovascular disease. This would include a history of severe palpitations, fainting, exercise intolerance not accounted for by obesity, or strong family history of sudden death. Postoperative tetralogy of Fallot, coronary artery abnormalities, and subaortic stenosis are known cardiac problems that require special considerations in using stimulants. Chest pain, arrhythmias, hypertension, or syncope may be signs of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, which has been associated with sudden unexpected deaths in children and adolescents. Before a stimulant trial, such patients should be referred for consultation with a cardiologist for possible electrocardiography and/or echocardiography. If stimulants are initiated, then the patient should also be studied by the cardiologists during the course of treatment.

SIDE EFFECTS OF NON-FDA-APPROVED AGENTS

Bupropion may cause mild insomnia or loss of appetite. Extremely high single doses (>400 mg) of bupropion may induce seizures even in patients without epilepsy. TCAs frequently cause anticholinergic side effects such as dry mouth, sedation, constipation, changes in vision, or tachycardia. Reduction in dose or discontinuation of the TCA is often required if these side effects induce impairment. Side effects of α-agonists include sedation, dizziness, and possible hypotension. In the previous decade there was controversy over the safety of the use of α-agonists, particularly clonidine, in children. Swanson and colleagues (1995) noted about 20 case reports of children suffering significant changes in heart rate and blood pressure, particularly after clonidine dose adjustment. Four cases of death were reported in children taking a combination of MPH and clonidine, but there were many atypical aspects of these cases (Popper, 1995; Swanson et al., 1995, 1999b; Wilens and Spencer, 1999), and Wilens and Spencer (1999) doubted any causative relationship between the stimulant-agonist combination and the patients' deaths. There have been no further reports of severe cardiovascular adverse events associated with clonidine use in ADHD patients. Nonetheless, physicians must be cautious. The patient's blood pressure and pulse should be assessed periodically (Gutgesell et al., 1999), and abrupt discontinuations of the α-agonist are to be avoided. The patient and family should be advised to report any cardiac symptoms such as dizziness, fainting, or unexplained change in heart rate.

Recommendation 10. If a patient with ADHD has a robust response to psychopharmacological treatment and subsequently shows normative functioning in academic, family, and social functioning, then psychopharmacological treatment of the ADHD alone is satisfactory [OP].

Whether combined medication and psychosocial treatment of uncomplicated ADHD yields improved outcome relative to medication treatment alone remains a contentious issue. For children with ADHD alone who do not have significant comorbidity, the MTA and M+MPT studies do not for the most part show an additive effect of the psychosocial interventions. In the first set of analyses of the MTA data, the four groups were compared over time on quantitative measures of ADHD symptoms; there was no significant difference between the comprehensive medication management group and the combined treatment group. In a subsequent set of analyses, an advantage for the combined treatment was seen. Swanson et al. (2001 [rct]) created a “categorical” outcome measure using the Swanson, Nolan, and Pelham (SNAP) behavior rating scale. Successful treatment was defined as having an average symptom rating no greater than 1.0 (“just a little”). Using this definition, 68% of the combined group was optimally treated, compared with 56% of the medication-only group, a statistically significant difference. Behavioral treatment alone remained inferior to medication management, with only 34% of the behavioral treatment group maximally improved.

Combined treatment did not yield superior outcome to medication only in the M+MPT study. After 2 years of intensive psychosocial intervention and MPH, children with ADHD (without learning problems or comorbidities) were no different from those treated with medication alone in terms of ADHD symptoms (Abikoff et al., 2004b [rct]), academics (Hechtman et al., 2004 [rct]), or social skills (Abikoff et al., 2004a [rct]). Children in the MTA study were studied for 1 year after the end of active intervention. No benefit of combined treatment was found over medication alone, and stopping medication was strongly related to deterioration (MTA Cooperative Group, 2004a [rct], 2004b [rct]). Overall, the data suggest that for ADHD patients without comorbidity who have a positive response to medication, adjunctive psychosocial intervention may not provide added benefit. Therefore, if a patient with ADHD shows full remission of symptoms and normative functioning, it is not mandatory that behavior therapy be added to the regimen, although parental preferences in this matter should be taken into account.

Recommendation 11. If a patient with ADHD has a less than optimal response to medication, has a comorbid disorder, or experiences stressors in family life, then psychosocial treatment in conjunction with medication treatment is often beneficial [CG].

In contrast to the lack of an additive effect of behavioral and pharmacological treatment in children with ADHD alone, the MTA study provided strong evidence that patients with ADHD and comorbid disorders and/or psychosocial stressors benefit from an adjunctive psychosocial intervention. Comorbid anxiety (as reported by the child's parent) predicted a better response to behavioral treatment (March et al., 2000 [rct]), particularly when the ADHD patient had both an anxiety and a disruptive behavior disorder (ODD or CD; Jensen et al., 2001b [rct]). Children receiving public assistance and ethnic minorities also showed a better outcome with combined treatment (Arnold et al., 2003 [rct]; MTA Cooperative Group, 1999b [rct]). Thus, the clinician should individualize the psychosocial intervention for each ADHD patient, applying it in those patients who can most benefit because of comorbidity or the presence of psychosocial stress.

Recommendation 12. Patients should be assessed periodically to determine whether there is continued need for treatment or if symptoms have remitted. Treatment of ADHD should continue as long as symptoms remain present and cause impairment [MS].

The patient with ADHD should have regular follow-up for medication adjustments to ensure that the medication is still effective, the dose is optimal, and side effects are clinically insignificant. For pharmacological interventions, follow-up should occur at least several times per year. The number and frequency of psychosocial interventions should be individualized as well. The procedures performed at each office visit will vary according to clinical need, but during the course of annual treatment, the clinician should review the child's behavioral and academic functioning; periodically assess height, weight, blood pressure, and pulse; and assess for the emergence of comorbid disorders and medical conditions. Psychoeducation should be provided on an ongoing basis. The need to initiate formal behavior therapy should be assessed and the effectiveness of any current behavior therapy should be reviewed.

The history of medication treatment of ADHD now spans nearly 70 years, which is longer than the use of antibiotics (Bradley, 1937). The MTA clearly showed that once the study treatments ceased at 14 months, the combined and medication groups lost some of their treatment gains, in part because of medication discontinuation and in part because the medication was now being given in the community with less careful monitoring and dose adjustment (MTA Cooperative Group, 2004a [rct], 2004b [rct]). In contrast, in the M+MPT study, all of the medication treatment was performed in the study. There was no deterioration in clinical effect or compliance, even in the second year, when the intensity of psychosocial treatment was greatly reduced (Abikoff et al., 2004b [rct]; Klein et al., 2004 [rct]). Given the high level of maladaptive behavior among adolescents with ADHD (Barkley et al., 2004), continued psychopharmacological intervention through this developmental period is likely to be highly beneficial. At the time of the 1997 AACAP practice parameter on ADHD, few long-term medication treatment studies of children with ADHD were available. One of the first controlled long-term stimulant studies studied the effects of DEX (Gillberg et al., 1997 [rct]). Children with ADHD (n = 62) were successfully treated with DEX in a short-term, open-label trial and then randomized to either placebo or DEX in a double-blind, parallel-group design for up to 1 year of treatment. Significantly more children relapsed in the placebo group (71%) than in the DEX group (29%), and the stimulant group showed significantly more improved ratings on the Conners Parent Rating Scales than the placebo group as the study progressed.