Cultural Formulation: From the APA Practice Guideline for the Psychiatric Evaluation of Adults, 2nd Edition

Cultural formulation

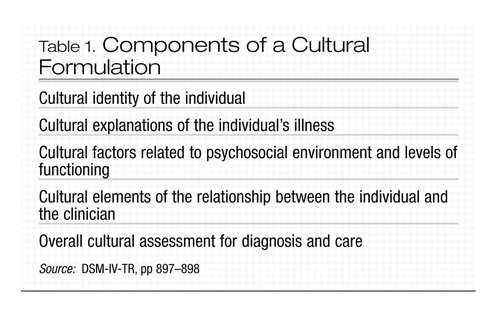

The DSM-IV-TR Outline for Cultural Formulation (Table 1) provides a systematic method of considering and incorporating sociocultural issues into the clinical formulation (1–5). Depending on the focus and extent of the evaluation, it may not be possible to do a complete cultural formulation based on the findings of the initial interview. However, when cultural issues emerge, they may be explored further during subsequent meetings with the patient. In addition, the information contained within the cultural formulation may be integrated with the other aspects of the clinical formulation or recorded as a separate element.

The cultural formulation begins with a review of the individual’s cultural identity and includes the patient’s self-construal of identity over time (6). Cultural identity involves not only ethnicity, acculturation/biculturality, and language but also age, gender, socioeconomic status, sexual orientation, religious and spiritual beliefs, disabilities, political orientation, and health literacy, among other factors.

Next, the formulation explores the role of the cultural context in the expression and evaluation of symptoms and dysfunction, including the patient’s explanatory models or idioms of distress through which symptoms or needs may be communicated. These are assessed against the norms of the cultural reference group. Treatment experiences and preferences (including complementary and alternative medicine and indigenous approaches) are also identified. Cultural factors related to psychosocial stressors, available social supports, and levels of function or disability are also assessed, highlighting the roles of family/kin systems and religion and spirituality in providing emotional, instrumental, and informational support.

The cultural formulation also includes specific consideration of cultural elements influencing the relationship between the individual and the clinician. In this regard, it is important for clinicians to cultivate an attitude of “cultural humility” (7) in knowing their limits of knowledge and skills rather than reinforcing potentially damaging stereotypes and overgeneralizations. Differences in language, culture, or social status as well as difficulties in identifying and understanding the cultural significance of behaviors or symptoms may add to the complexities of the clinical encounter. Transference and countertransference may also be influenced by cultural considerations and may either aid or interfere with the treatment relationship. Further, the potential effect of the psychiatrist’s sociocultural identity on the attitude and behavior of the patient should be taken into account in the subsequent formulation of a diagnostic opinion.

The cultural formulation concludes with an overall assessment of the ways in which these varied cultural considerations will specifically apply to differential diagnosis and treatment planning.

|

Table 1. Components of a Cultural Formulation

1 Lu F, Lim R, Mezzich J: Issues in the assessment and diagnosis of culturally diverse individuals, in American Psychiatric Press Review of Psychiatry, vol 14. Edited by Oldham J, Riba M. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1995, pp 477–510Google Scholar

2 Group for the Advancement of Psychiatry: Cultural Assessment in Clinical Psychiatry. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Publishing, 2002Google Scholar

3 Koskoff H: The Culture of Emotions (video recording). Boston, Fanlight Productions, 2002Google Scholar

4 Lim R: Cultural Psychiatry for Clinicians. Baltimore, Johns Hopkins University Press (in press)Google Scholar

5 Hays P: Addressing Cultural Complexities in Practice: A Framework for Clinicians and Counselors. Washington, DC, American Psychological Association, 2001Google Scholar

6 Weinreich P, Saunderson W: Analyzing Identity: Cross-Cultural, Societal, and Clinical Contexts. New York, Routledge, 2003Google Scholar

7 Tervalon M, Murray-Garcia J: Cultural humility versus cultural competence: a critical distinction in defining physician training outcomes in multicultural education. J Health Care Poor Underserved 1998; 9:117–125Crossref, Google Scholar