Gender Identity and Psychosexual Disorders

This chapter provides an overview of gender identity and psychosexual problems in children and adolescents. Three terms—gender identity, gender role, and sexual orientation—are useful in organizing a conceptual framework in thinking about these issues.

Gender identity refers to a person’s basic sense of self as male or female. It includes both the awareness that one is male or female and an affective appraisal of such knowledge. In the clinical literature, the term gender dysphoria has been used to characterize a person’s sense of discomfort or unease about his or her status as male or female. Based on clinical work with children born with physical intersexual conditions, Money et al. (1957) concluded that gender identity typically appears in its nascent form between ages 2 and 3 years. During the past four decades, this original clinical observation has been buttressed by normative empirical studies, which have demonstrated that children in this age range—typically by about 30–36 months—are able to categorize people by sex on the basis of phenotypic social cues, such as clothing and hairstyle (for reviews, see Ruble and Martin 1998; Zucker et al. 1999). According to some researchers, this ability likely precedes the ability to self-categorize oneself as a boy or a girl.

Gender role refers to a person’s behavioral adoption of cultural markers of masculinity and femininity. In children, gender role preference can be measured in a variety of ways, including playmate affiliations, toy interests, role and fantasy play, and endorsement of various personality attributes. Conceptually, one can consider a child to be primarily masculine or feminine based on the pattern of gender role behavior. Alternatively, one can view a child as both masculine and feminine (androgynous) or as neither masculine nor feminine (undifferentiated). Over the past 50 years, many studies have been conducted on gender role behavior in children (Ruble and Martin 1998). Almost without exception, these studies have shown that boys and girls differ significantly with regard to several sex-typed attributes, including toy and fantasy play (Fagot 1977), peer affiliation preference (Maccoby 1998; Maccoby and Jacklin 1987), aggression (Maccoby and Jacklin 1974, 1980), activity level (Benenson et al. 1997; Campbell and Eaton 1999; Eaton and Enns 1986), and rough-and-tumble play (DiPietro 1981).

Sexual orientation refers to the pattern of a person’s erotic responsiveness. Heterosexual, bisexual, and homosexual are the three sexual orientations most commonly described by contemporary nosologists in sexology, although it is also important to consider the age of the sexual partner (either in fantasy or in behavior), as in heterosexual or homosexual pedophilia. Gender identity and gender role are typically viewed as developing before the emergence of sexual orientation, although this view is not held universally (Isay 1989).

Diagnostic criteria

In DSM-IV-TR (American Psychiatric Association 2000), four diagnoses are of relevance with regard to gender identity and psychosexual problems during childhood and adolescence:

| 1. | |||||

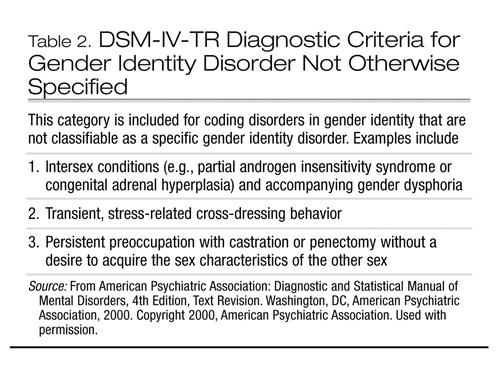

| 2. | Gender identity disorder not otherwise specified (GIDNOS) (Table 2) | ||||

| 3. | |||||

| 4. | |||||

During childhood, only the first two of these four diagnoses are of relevance. In adolescence, however, all of these diagnoses may be utilized as gender identity and psychosexual concerns become more differentiated, in part because of the increased salience of erotic behavior. Therefore, in addition to concerns about gender identity proper (which can be diagnosed with either GID or its residual diagnosis, GIDNOS), the clinician must also be attentive to paraphilic behavior (transvestic fetishism) or distress regarding one’s sexual orientation, most typically in homosexuality (sexual disorder not otherwise specified).

Only one study has formally evaluated the reliability of the GID diagnosis in children, which was based on the criteria from DSM-III (American Psychiatric Association 1980). Based on chart data from 36 consecutive referrals to a child and adolescent gender identity clinic, Zucker et al. (1984) found high agreement with DSM-III criteria for GID. Validity evidence was also found: the children who met the complete diagnostic criteria were, on average, more cross-gendered in their behavior than were the children who did not meet the complete diagnostic criteria. Subsequent analyses with larger numbers of children have verified this distinction (Zucker and Bradley 1995; Zucker et al. 1992, 1993b).

Among demographic variables, age of the child at assessment has been most consistently associated with the GID diagnosis. Based on 488 consecutive referrals from two specialized gender identity clinics (one in Toronto, Ontario, Canada, and the other in Utrecht, the Netherlands), Cohen-Kettenis et al. (2003) found that the children who met the complete criteria for GID (mean age, 6.8 years) were significantly younger than the children who were subthreshold (mean age, 8.6 years). Elsewhere it was shown that children who met the complete diagnostic criteria were from a higher social class and were more likely to come from an “intact” two-parent family. Sex of the child and IQ were not associated with the presence or absence of the complete diagnostic criteria for GID (Zucker and Bradley 1995).

To test which variables contributed to the correct classification of the children in the two diagnostic groups, a discriminant-function analysis was performed (Zucker and Bradley 1995). Age, sex, IQ, and parents’ marital status contributed to the discriminant function, with age showing the greatest power. In the DSM-III group, 82.6% were correctly classified, and in the non-DSM-III group, 68.8% were correctly classified.

The data regarding age appear to be related to older children’s tendency not to verbalize the wish to be of the opposite sex, which was a distinct criterion for GID in both DSM-III and DSM-III-R (American Psychiatric Association 1987). Clinical evidence may suggest continued discomfort with gender identity issues, but the older child may be more aware of social convention and thus may not verbalize concerns, at least during an initial diagnostic assessment.

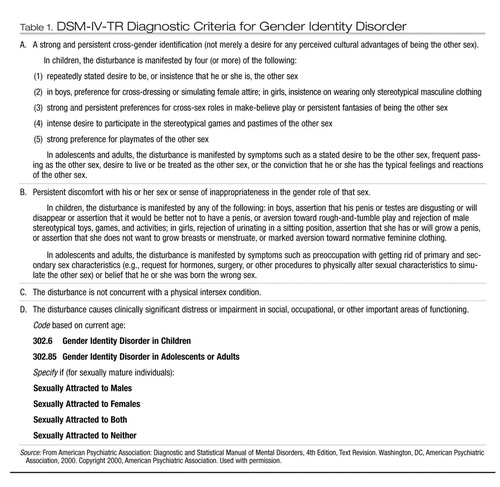

These findings led to the question of whether it was appropriate to retain the wish to be the opposite sex as a distinct criterion in DSM-IV (Bradley et al. 1991; Zucker et al. 1998). The DSM-IV Subcommittee on Gender Identity Disorders recommended that the verbalized wish to be the opposite sex should be collapsed with several other behavioral criteria to index the child’s cross-gender identification (see Criterion A in Table 1) (Bradley et al. 1991). In a reanalysis of an existing data set, Zucker et al. (1998) showed that this change somewhat reduced the influence of age on the likelihood of a child meeting the requirements in Criterion A.

Table 1 also shows Criterion B for the diagnosis of GID: the child’s sense of discomfort about his or her sex and the sense of inappropriateness in the gender role of that sex. At present, formal studies to fully evaluate the reliability and validity of the modified GID diagnosis for children have not been conducted.

Perhaps the most substantive change in the diagnostic criteria for GID in DSM-IV and DSM-IV-TR pertains to the inclusion of age-related criteria so that the diagnosis can be applied to all phases of the life cycle. This change resulted in the elimination of two diagnoses from DSM-III-R: 1) transsexualism and 2) gender identity disorder of adolescence or adulthood, nontranssexual type.

From a clinical point of view, the establishment of the GID diagnosis in adolescents requires that one pay close attention to the descriptors strong and persistent (Criterion A) and persistent discomfort (Criterion B). Unfortunately, no gold standard is available to make this kind of clinical judgment and, to date, there has been little in the way of systematic empirical research regarding the reliability and validity of the diagnosis in adolescents (see, however, Smith et al. 2001; Zucker and Bradley 1995).

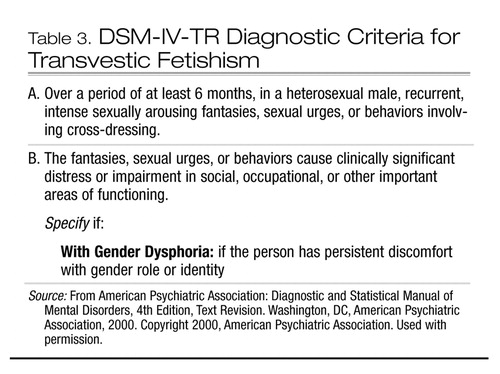

No formal empirical studies have been conducted to examine the reliability and validity of the diagnosis of transvestic fetishism in adolescents; however, the DSM-IV-TR diagnostic criteria for transvestic fetishism (see Table 3) are sufficiently loose to make their use with adolescents not particularly difficult (Zucker and Blanchard 1997; Zucker and Bradley 1995). Clinically, one encounters adolescents who display a range of fetishistic cross-dressing (e.g., from wearing women’s underwear while masturbating to complete cross-dressing accompanied by erotic arousal). Conceptually, clinicians should be interested in whether such behavior represents an erotic preference (Zucker and Blanchard 1997). With adolescents, this is not always clear, because many adolescent boys also display considerable heterosexual arousal and interaction without the use of feminine apparel. However, DSM-IV-TR criteria for transvestic fetishism do not address the issue of erotic preference.

In DSM-IV-TR, the term autogynephilia was introduced as a new descriptive construct, giving recognition to its increased clinical use in understanding the linkage between transvestic fetishism and GID. The term autogynephilia was constructed from Greek roots meaning “love of oneself as a woman” and has been defined as a male’s propensity to be sexually aroused by the thought or image of himself as a female (for review, see Zucker and Blanchard 1997). It is most commonly the case that transvestic adolescents who experience autogynephilic feelings and fantasies are the ones who will present with the request for sex-reassignment surgery.

Clinical findings

Phenomenology

Children with GID present with a rather coherent set of behavioral signs. In a boy, these signs include making verbal statements that he is, or would like to be, a girl; cross-dressing in girls’ or women’s clothing; having a preference for culturally stereotypical feminine toys and activities; emulating females in fantasy play; having a preference for girls as playmates; expressing dislike of his sexual anatomy (e.g., concealing his penis, sitting to urinate in order to embellish the fantasy of having female genitalia); and being averse to rough-and-tumble play and group sports. In a girl, the inverse is observed. Of particular note is the intense aversion to culturally stereotypical girls’ clothing and the desire to have her hairstyle look like that of a boy, such that a naive observer would perceive her as male. Taken together, these characteristics point to the child’s very strong cross-gender identification, and several research studies have established their discriminant validity or relative uniqueness (Green 1974, 1987; Zucker 1985, 1992; Zucker and Bradley 1995).

Apart from the features of GID described in the formal DSM diagnostic criteria, there are other aspects that have been noted clinically and empirically. For example, many clinicians have observed how intense and rigid cross-gender identification can be in these youngsters (Coates 1990, 1997; Coates and Wolfe 1995, 1997), and sometimes this extends into domains that surprise even the most sophisticated practitioner. One example of this pertains to sex-typed color preferences, which some gender theorists might characterize as an overelaborated gender schema (Ruble and Martin 1998). Clinically, one is often impressed by the rigidity of color choices by children with GID. For example, the boys invariably prefer pink and purple, as exemplified, perhaps, in the critically acclaimed film Ma Vie en Rose (My Life in Pink), about a boy with GID (Kline 1998). One can observe this in the type of clothing that they request and in their drawings, which are often of idealized, beautiful, and benevolent females. Girls with GID invariably reject colors like pink and purple and will often prefer dark colors, such as blue and black. About 10% of boys with GID appear preoccupied not with benevolent females but with malevolent ones: they endlessly draw pictures of angry, hostile females, such as the Wicked Witch of the West, Cruella De Vil from 101 Dalmatians, or Ursula from The Little Mermaid.

The study of the child’s actual sense of gender identity has been somewhat more complicated. Most children with GID “know” that they are male or female; that is, if they are asked the question “Are you a boy or a girl?” they answer correctly (Zucker et al. 1993b). Some of these youngsters, however, do not seem to know the answer or else appear to be confused about their gender status (i.e., whether they are male or female). In part, this may be a developmental phenomenon, but it also may be a sign of the severity of the overall condition (Stoller 1968a). Indeed, Zucker et al. (1999) reported evidence for a developmental lag in acquisition of gender constancy among children with GID.

The child’s internal representation of gender has been more difficult to study, although clinical experience suggests that the stability of the gender sense can be quite labile in some children. Zucker et al. (1993b) reported the results of a gender identity interview schedule that identified two factors, tentatively labeled cognitive gender confusion and affective gender confusion, both of which discriminated children referred for gender identity problems from clinical and nonclinical control subjects. The following responses were given by an 8-year-old boy (IQ, 133) who, by parent report, met DSM-IV criteria for GID:

Interviewer (I): Are you a boy or a girl?

Child (C): Both.

I: Are you a girl?

C: Kind of.

I: When you grow up, will you be a mom or a dad?

C: Don’t know.

I: Could you ever grow up to be a mom?

C: Yes.

I: Are there any good things about being a boy?

C: Yes.

I: Tell me some of the good things about being a boy.

C: Boys don’t have to have babies and get their spine ripped open . . .

I: Are there any things that you don’t like about being a boy?

C: Yes.

I: Tell me some of the things that you don’t like about being a boy.

C: . . . Everything. Please don’t make me tell.

I: Do you think it is better to be a boy or a girl?

C: Girl.

I: Why?

C: There are so many reasons. Girls are more mature . . . positive . . . better . . .

I: In your mind, do you ever think that you would like to be a girl?

C: Yes.

I: Can you tell me why?

C: Because the guys don’t accept me for what I am. . . . Girls have better bands, like the Spice Girls.

I: In your mind, do you ever get mixed up and you’re not really sure if you are a boy or a girl?

C: Yes.

I: Tell me more about that.

C: Practically all the time. I think the doctor was totally wrong and deformed me. I am a woman in a man’s body. He gave me a girl’s mind and switched brains or bodies.

I: Do you ever feel more like a girl than like a boy?

C: Yes.

I: Tell me more about that.

C: Well, I do lots of times, especially when I’m in the bath. . . . This is going way too deep. . . . Well, usually girls want me to play their games. . . . Then I get mixed up being a girl or a boy.

I: You know what dreams are, right? Well, when you dream at night, are you ever in the dream?

C: Yes.

I: In your dreams, are you a boy, a girl, or sometimes a boy and sometimes a girl?

C: Both. . . . it’s just me as a girl, me and my friends . . . find out the secret of being trapped in a boy’s body. We go to the doctor’s to find out, look into his files and find nothing about me. Then we destroy him.

I: Do you ever think that you really are a girl?

C: Yes.

I: Tell me more about that.

C: . . . Practically all the time . . . because of my feelings. . . . I want to be a lead singer of a girls’ band when I grow up.

Age at onset

Green (1976) reported that the age at onset of cross-gender behaviors in GID is typically during the preschool years. In his sample of boys, for example, 55% were cross-dressing by their third birthday, 80% were cross-dressing by their fourth birthday, and 90% were cross-dressing by their fifth birthday. Many experienced clinicians have observed that repetitive, intense cross-gender behaviors appear even before a child’s second birthday. Clinical data on girls reveal a similar age at onset (Zucker and Bradley 1995). It is important to note that among more typical children, a display of various gender role behaviors can also be observed during this period in the life cycle. This similarity suggests that the underlying mechanisms for both patterns may be the same, albeit mirror images.

Associated psychopathology

In DSM-IV-TR, it is noted that children with GID may have co-occurring behavioral difficulties, including social isolation, low self-esteem, separation anxiety, and depression. What are the data regarding the presence of other types of psychopathology in children with GID? If other forms of psychopathology are present, how is the association with GID to be understood?

Unfortunately, omnibus structured interview schedules that cover the gamut of childhood psychopathology have not been utilized in this clinical population. However, several more narrowly focused empirical studies have reported on the presence of general psychopathology in both boys and girls with GID (Coates and Person 1985; Cohen-Kettenis et al. 2003; Zucker and Bradley 1995). These studies have shown that both boys and girls with GID display levels of general psychopathology similar to those of demographically matched psychiatric control subjects and levels greater than those of control subjects without psychiatric disorders. For example, children with GID have been shown to display behavior problems at a level comparable to the clinic-referred standardization sample (Coates and Person 1985; Cohen-Kettenis et al. 2003; Zucker and Bradley 1995), as measured with the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) (Achenbach and Edelbrock 1981), a parent-report instrument of behavior problems. In boys with GID, internalizing problems were somewhat more common than externalizing problems, a finding that is consistent with clinical observations that many of these boys experience anxiety, depression, and social withdrawal (see also Zucker et al. 1996a). More generally, it should be noted that the overall functioning of children with GID varies considerably. Some of these youngsters show pervasive behavioral difficulties and often require intensive intervention for these problems in their own right; on the other hand, some youngsters show minimal behavioral psychopathology and function quite well in the different environments of daily life.

How might these associated behavioral difficulties be best understood? Zucker and Bradley (1995) provided data that showed that in boys with GID, behavioral difficulties based on CBCL measures increased with age. This was interpreted as being consistent with the influence of social ostracism, which becomes more pronounced over time. Two subsequent studies, utilizing a more direct measure of poor peer relations, confirmed this inference empirically; indeed, in a multiple regression analysis, it was the measure of poor peer relations, not age, that accounted for the most variance in predicting CBCL behavior problems in both boys and girls with GID (Cohen-Kettenis et al. 2003; Zucker et al. 2002).

A study by S.R. Fridell (unpublished doctoral dissertation, 2001) provided further evidence that the cross-sex-typed behavior of boys with GID may well be related to how well they are liked by other children. Fridell created 15 age-matched experimental play groups consisting of one boy with GID and two nonreferred boys and two nonreferred girls (age range, 3–8 years). After two 60-minute play sessions, conducted a week apart, each child was asked to select their favorite playmate from the group. The nonreferred boys most often chose the other nonreferred boy as their favorite playmate, thus indicating a distinct preference over the boy with GID. The nonreferred girls chose the other girl as their favorite playmate, thus showing a relative disinterest in either the boy with GID or the two nonreferred boys.

In another line of research, Zucker and Bradley (1995) showed that a composite measure of maternal psychopathology also predicted the extent of behavioral difficulties detected with the CBCL, which suggests that generic familial emotional and psychiatric factors also contribute to the degree of general psychopathology (see also Cohen-Kettenis et al. 2003; Zucker et al. 2002).

Another perspective on the nature of the associated psychopathology has been advanced by Coates and Person (1985), who provided data on a high rate of separation anxiety disorder in boys with GID. These researchers argued that the high rate of separation anxiety could be accounted for by a great deal of familial psychopathology, which rendered the mothers of these boys unpredictably available. The authors claimed that the emergence of the separation anxiety actually preceded the first appearance of the feminine behavior, which was understood to serve a representational coping function of recapturing an emotionally unavailable mother.

As noted elsewhere (Zucker and Green 1992), Coates and Person (1985) did not have empirical evidence available to document the putative temporal relation between separation anxiety and GID, because both diagnoses were made concurrently at the time of assessment. Rather, the temporal relation was inferred on the basis of clinical evidence. Subsequently, Zucker et al. (1996a) confirmed the high rate of co-occurring traits of separation anxiety disorder in boys with GID, and A.S. Birkenfeld-Adams (unpublished doctoral dissertation, 1999) has shown a rate of insecure attachment to the mother, but the temporal aspect of the hypothesis of Coates and Person (1985) remains to be tested.

Biophysical markers

By observation, it is apparent that the vast majority of children with GID do not have abnormalities in physical sex differentiation—such as in the various physical intersexual disorders—that might, on theoretical grounds, contribute to the condition (Meyer-Bahlburg 1994; Zucker 1999c). Because sex hormone levels are so low during childhood (Sizonenko 1980), it is unlikely that a standard endocrine assessment would detect abnormalities. Green (1976) and Rekers et al. (1979) reported normal XY karyotypes in boys with GID. Green also found that the feminine boys he studied did not differ in height and weight from nonfeminine boys at the time of assessment (Roberts et al. 1987), although they were hospitalized more often before their participation in the study.

However, if one starts with a sample of children or adolescents with certain physical intersexual conditions, such as genetic females with congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH) raised as girls, genetic males with partial androgen insensitivity syndrome raised as girls, and genetic males with cloacal exstrophy raised as girls, gender identity problems or gender dysphoria appears to be present in a subgroup of these youngsters (for reviews, see Zucker 1999c, 2002). However, these conditions are invariably already known to the clinician at the time of diagnostic assessment.

Differential diagnosis

Diagnostic issues in children

Several diagnostic issues require consideration in relation to GID. A small number of boys engage in a type of cross-dressing that appears to be quite different from the type of cross-dressing that is part of the clinical picture in GID. In the latter, cross-dressing encompasses a range of behaviors, including the wearing of dresses, women’s shoes, and jewelry, all of which enhance the fantasy or desire to be like the opposite sex. In the former, cross-dressing is limited to the use of undergarments, such as panties and nylons. As with boys with GID, the cross-dressing has a compulsive and self-soothing flavor to it. However, it is not accompanied by other signs of cross-gender identification; in fact, apart from the cross-dressing, these boys are conventionally masculine (Zucker and Blanchard 1997). Many male adolescents and adults who have a diagnosis of transvestic fetishism recall such cross-dressing during childhood (Zucker and Bradley 1995); however, no prospective studies of prepubertal boys engaging in this form of cross-dressing have been conducted to determine what proportion, if any, of these boys develop transvestic fetishism.

When all of the clinical signs of GID are present, there is little difficulty in making the diagnosis. If one accepts the idea of a spectrum of cross-gender identification, then there is more room for ambiguity, and one must be prepared to identify what Meyer-Bahlburg (1985) referred to as the “zone of transition between clinically significant cross-gender behavior and mere statistical deviation from the gender norm” (p. 682).

Friedman (1988), for example, suggested that there is a subgroup of boys who are “unmasculine” but not feminine. Based on clinical experience, Friedman argued that these boys have a “persistent, profound feeling of masculine inadequacy which leads to negative valuing of the self” (p. 199). Although it is not described in the formal clinical literature, there is also probably a subgroup of girls who are “unfeminine” but not masculine and may have similar feelings. Such youngsters would not meet DSM-IV-TR criteria for GID, but the residual diagnosis of GIDNOS could be used in such cases.

For girls, the main differential diagnostic issue concerns the distinction between GID and what is known in popular culture as tomboyism. According to Webster’s Ninth New Collegiate Dictionary, a tomboy is “a girl of boyish behavior.” Green et al. (1982) studied a community sample of tomboys and found that, compared with a control group of nontomboys, tomboys displayed a greater number of masculine traits, such as a preference for boys as playmates, interest in rough-and-tumble play, and play with guns and trucks. In many respects, the cross-gender behavior of such tomboys is similar to the masculine gender role preferences of girls who are referred clinically for gender identity concerns (Bailey et al. 2002; Zucker and Bradley 1995).

Based on critiques of DSM-III criteria for GID in girls (Zucker 1982), DSM-III-R and DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association 1994) criteria for girls were modified in the hope of better differentiating these two groups. Clinical experience suggests that at least three characteristics are useful in making a differential diagnosis. First, girls with GID express a profound unhappiness with their female gender status; in contrast, Green (1980) noted that his sample of tomboys were “generally content being female” (p. 262). Second, girls with GID display a marked aversion to culturally defined feminine clothing and will do their utmost to avoid having to wear it. Their refusal to wear “girls’ clothes” under any circumstance often precipitates clinical referral. Although tomboys prefer functional and casual clothing (Green et al. 1982), they do not display the same type of rigid rejection of feminine clothing. Third, girls with GID, unlike tomboys, often express discomfort with or dislike of their sexual anatomy.

Diagnostic issues in adolescents

The clinician will encounter at least four types of psychosexual problems among adolescents (Bradley and Zucker 1990; Zucker and Bradley 1995). First, clinical experience suggests that persistent cross-gender identification throughout childhood is a risk factor for the continuation of GID into adolescence and adulthood. As noted earlier, it is important to evaluate the fixedness of the desire to change sex, because therapeutic decisions will be influenced, at least to some extent, by the adolescent’s openness to consider alternatives to sex reassignment (Newman 1970). From a differential diagnostic standpoint, the residual diagnosis of GIDNOS can be used for individuals whose desire to change sex does not quite fit the criteria for GID.

The second psychosexual problem that can be observed in adolescents involves individuals who have a history of GID or a subclinical variant. These adolescents show various signs of cross-gender identification but do not voice a desire to change sex. They are circumspect about their sexual orientation, so it is not possible to classify them as homosexuals. These youngsters often are referred because of continued social ostracism. Many of these adolescents are able to acknowledge distress about not “fitting in” because of their cross-gender behavior. In these cases, the residual diagnosis of GIDNOS could be used to indicate that the adolescent continues to struggle with gender identity concerns.

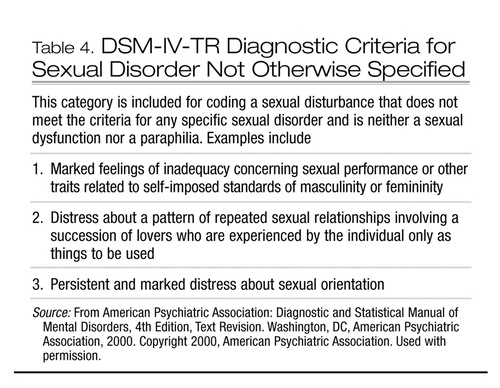

A third type of psychosexual problem involves adolescents who have been referred because of homosexual behavior or orientation. Many of these adolescents have a history of GID or a variation of it, perhaps akin to the unmasculinity described by Friedman (1988; see also Friedman and Downey 2002; Friedman and Stern 1980). Although the reason for referral varies, it is important to rule out continuing concerns about gender identity. For adolescents distressed about their sexual orientation, the diagnosis of sexual disorder not otherwise specified can be given.

The last type of psychosexual problem is, as far as we know, the exclusive domain of adolescent males: cross-dressing associated with sexual arousal. As noted earlier, the extent of the cross-dressing varies and there is no problem, in principle, in employing the diagnosis of transvestic fetishism. As noted with adults with transvestic fetishism, a heterosexual orientation predominates. A history of GID is not part of the clinical picture, although some of these boys think about sex-reassignment surgery and are at risk for GID. Although the clinical course of GID in males with a history of transvestic fetishism seems to develop more slowly than does GID in males who are sexually attracted to other biological males (Blanchard 1994; Blanchard et al. 1987), there is now considerable clinical evidence to suggest that even among adolescents with transvestic fetishism the presence of autogynephilic feelings can be substantial, thus resulting in rather intense gender dysphoria, leading to the desire for sex-reassignment surgery.

In DSM-III-R, the diagnosis of transsexualism (GID in DSM-IV) was an exclusionary criterion for transvestic fetishism, but this was shown to be clinically inaccurate (Blanchard and Clemmensen 1988). In DSM-IV-TR, the diagnosis of transvestic fetishism allows the co-occurrence of gender dysphoria to be specified (see Table 3).

Epidemiology

Prevalence

No studies have been designed to specifically assess the prevalence of GID in children. Nevertheless, the characterization of GID by Meyer-Bahlburg (1985) as a rare phenomenon is not unreasonable. If one accepts the assumption that GID in childhood is associated with its continuation into adulthood, then conservative estimates of prevalence in childhood might be inferred from epidemiological data on GID in adults. Bakker et al. (1993) inferred the prevalence of GID in adults in the Netherlands from the number of persons receiving cross-gender hormonal treatment at the main adult gender identity clinic in that country: 1 in 11,000 men and 1 in 30,400 women.

However, this approach has at least three limitations: first, it relies on the number of persons who attend specialty clinics serving as gateways for surgical and hormonal sex reassignment, which may not include all gender-dysphoric adults. Second, the assumption that GID in children will in fact persist into adulthood is not necessarily true (see “Prognosis” section below). Nevertheless, prevalence estimates of GID in children derived from data on adults support the notion of its rarity. Last, unlike adult women with gender dysphoria, who are predominantly sexually attracted to biological females (but see Chivers and Bailey 2000), adult men with gender dysphoria are about equally likely to be sexually attracted to biological males or females (Blanchard et al. 1987). A childhood history of GID or its subclinical manifestation occurs largely among adults with gender dysphoria and a homosexual sexual orientation. Estimates of the prevalence of childhood GID inferred from the prevalence of GID in men should take this into account.

Current prospective evidence indicates that GID in childhood is associated with subsequent homosexuality (see “Prognosis” below). There also is substantial retrospective evidence that homosexual men and women are more likely than heterosexual men and women to recall engaging in various cross-gender behaviors during childhood (Bailey and Zucker 1995). Accordingly, the literature on the epidemiology of homosexuality might also help to gauge the prevalence of GID.

Unfortunately, the true prevalence of exclusive, or nearly exclusive, homosexuality is a source of contention. Many authorities now acknowledge that the widely quoted 10% prevalence rate of homosexuality in men, which was culled from the work of Kinsey et al. (1948), is erroneous but has continued to be cited for political reasons (Begley 1991). Scholars who have reworked the Kinsey terrain suggest much lower prevalence rates, typically between 2% and 6% for men and about 2% for women (Diamond 1993; Rogers and Turner 1991). Even lower estimates for men and women have emerged from studies pertaining to the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) epidemic (Laumann et al. 1994; Spira et al. 1994; Wellings et al. 1994).

Another problem is that the retrospective literature on childhood cross-gender behavior in homosexual men and women often does not indicate how to classify individuals as either cross-gendered or not cross-gendered. Moreover, patients classified as cross-gendered would not necessarily meet the complete DSM-IV-TR diagnostic criteria for GID (Friedman 1988).

Liberal estimates of prevalence can be derived from studies on children in whom individual cross-gender behaviors have been assessed. For example, in one study of parents’ responses on the CBCL (Achenbach and Edelbrock 1981), the percentage of mothers of nonreferred 4- to 13-year-old boys grouped at 2-year intervals who endorsed the item “behaves like opposite sex” ranged from 0.7% in boys ages 12–13 to 6.0% in boys ages 4–5 years. Among nonreferred girls, maternal endorsement of this item was higher, ranging from 9.6% to 12.9%. For the item “wishes to be of opposite sex,” the endorsement was lower for both sexes, ranging from 0% to 5.0% in specific sex-by-age groupings. Similar results were obtained from another parent report questionnaire—the Achenbach-Connors-Quay Behavior Checklist (Achenbach et al. 1991)—which contained 3 items pertaining to cross-gender identification out of a total of 215 (2 from the original CBCL and a third, “dresses like or plays at being opposite sex”). If anything, endorsement of these items appeared to be less common on the new questionnaire than on the original CBCL, which supports the general point that extreme cross-gender behavior is relatively uncommon. This kind of information no doubt overestimates caseness, although the method of data collection might be a reasonable screening device for more intensive evaluation (Pleak et al. 1989).

Incidence

No adequate epidemiological data are available to address the question of whether the incidence of GID has changed over the years.

Referral rates

Prevalence and incidence issues aside, there has been a consistent observation that boys are more often referred than girls for gender identity concerns. In two specialized gender identity clinics for children—one in Toronto, Canada, and the other in Utrecht, the Netherlands—the sex ratio was 4.7:1 favoring boys over girls (N=488) (Cohen-Kettenis et al. 2003). However, the sex ratio was significantly larger in the Toronto clinic than in the Utrecht clinic (5.8:1 versus 2.9:1).

There are at least two explanations for this strong sex difference in referral rates. First, it may well be that boys are more vulnerable to GID than are girls, much as they are to a variety of other child psychiatric conditions (Eme 1979). Second, cultural factors appear to be related to differential tolerance of cross-gender behavior in boys versus girls. In childhood, cross-gender behavior in girls is less subject to negative sanctions than it is in boys by both peers and parents (Fagot 1985; Langlois and Downs 1980; Zucker et al. 1995). In fact, Cohen-Kettenis et al. (2003) showed that boys with GID had significantly poorer peer relations than girls with GID in both the Toronto clinic and in the Utrecht clinic. Moreover, adults are more likely to link cross-gender behavior in boys to atypical outcomes, such as homosexuality, than they are in girls (Antill 1987; Martin 1990). Both Cohen-Kettenis et al. (2003) and Zucker et al. (1997a) provided data to suggest that girls with GID need to display more extreme cross-gender behaviors than do boys to elicit a referral. Therefore, cases of GID in girls may be under-referred because of greater acceptance of girlhood masculinity.

Etiology

Biological mechanisms

The search for biological determinants of human psychosexual development—gender identity, gender role, and sexual orientation—has been a slow and complex endeavor, despite a great deal of effort on the part of many researchers. These researchers disagree on several issues. Do biological factors exert fixed versus predisposing influences on the components of psychosexual development? Can animal models be useful in understanding human phenomena? Are there unwanted political implications of advancing a biological explanation for human psychosexual development? These questions and others have been subject to intense debate within the field of sexual science over the years.

At present, researchers have been unable to identify a clear biological anomaly or variant associated specifically with GID. There is evidence, however, that certain behavioral traits linked to biological processes may characterize children with GID. The relation to biological variables also relies on data from allied populations from which generalizations might be made.

Prenatal sex hormones

Although circulating sex hormones probably have little causal effect on gender identity, gender role, and sexual orientation, considerable attention has been accorded to the influential role of the prenatal hormonal environment and its effect on psychosexual differentiation. Experimental studies—conducted in animal models ranging from mice to monkeys—have shown quite clearly how manipulation of the prenatal hormonal milieu can affect postnatal sex-dimorphic behavior (Meyer-Bahlburg 1984). Is there evidence that prenatal hormonal variations in humans, due to either endogenous anomalies or exogenous manipulation, exert effects that are consistent with those that have been observed in lower animals? Reviews of this complex literature suggest that there is enough consistency to pursue the lead (Collaer and Hines 1995).

One may consider, for example, studies of CAH, the most common physical intersexual condition that affects genetic females. This autosomal recessive disorder is associated with enzyme defects that result in abnormal adrenal steroid biosynthesis. Because of the high level of androgen production during fetal development, masculinization of the external genitalia is common. Based on data from lower animals and from theory, it has been presumed that some masculinization of the organ of behavior, the brain, may also have occurred.

As reviewed elsewhere (Collaer and Hines 1995; Zucker 1999c), there is evidence that the gender role behavior of girls with CAH is more masculine or less feminine than that of unaffected control subjects. The impact of CAH on gender identity is less clear, although the percentage of affected individuals who express some ambivalence about being female or who have been reared as boys (in part because the condition was untreated) is probably higher than among girls in the general population (Meyer-Bahlburg 1994; Meyer-Bahlburg et al. 1996). Adult follow-up studies of girls with CAH suggest that they have higher rates of bisexuality and homosexuality (particularly in fantasy) and lower rates of marriage and sociosexual experiences than would be expected otherwise (Dittmann et al. 1992; Money et al. 1984; Mulaikal et al. 1987; Zucker et al. 1996b).

Despite the rather obvious role of the hormonal anomaly in explaining the overall pattern, it is important to note that individual differences in outcome occur, and the determinants of such variation remain open to debate (Berenbaum 1990; Dittmann et al. 1992; Ehrhardt and Baker 1974). It is not clear, for instance, to what extent differences result from the severity of the disorder, from biomedical sequelae of the condition, or from social factors, such as how parents’ understanding of the condition might affect their socialization techniques vis-à-vis gender.

Can this body of data help us understand the genesis of GID? As noted above (see “Biological Mechanisms”), no identifiable hormonal anomaly seems to characterize children with this disorder. Perhaps, however, less pronounced variations in the prenatal hormonal milieu that do not affect genital differentiation but that do account in part for intra-sex differences in the expression of sex-dimorphic behavior play a role. For example, an avoidance of rough-and-tumble play and a low activity level both appear to be part of the clinical picture in boys with GID (Green 1987; Zucker and Bradley 1995). Both of these behaviors show a strong sex dimorphism (Eaton and Enns 1986) and are probably partly determined by biological factors. Such behavioral traits, coupled with the anxiety often observed clinically in such boys (Coates 1990; Zucker and Bradley 1995), may set in motion a complex chain of psychosocial sequelae that predispose to cross-gender identification (Green 1987).

Physical appearance

In a small-scale clinical study of extremely feminine boys, Stoller (1968b, 1975) noted that the mothers commented on their sons’ extreme physical beauty as infants, particularly the face. Although Stoller (1975) suggested that this description may have been a bit of an exaggeration, he was impressed by these boys’ physical appearance: “We have noticed that they often have pretty faces, with fine hair, lovely complexions, graceful movements, and—especially—big, piercing, liquid eyes” (p. 43). In Stoller’s view, the physical beauty of the boy fueled the mother’s conscious and unconscious desires to feminize her son.

Green and colleagues (Green 1987; Green et al. 1985; Roberts et al. 1987) systematically studied physical attractiveness in a larger sample of feminine and control boys. Masked ratings of audio-taped interviews showed that the parents of the feminine boys were more likely than the parents of the control boys to describe their sons during infancy as “beautiful” and “feminine.” Green (1987) found that the degree of recalled beauty correlated with ratings of maternal encouragement of feminine behavior. Green’s data suggest that these boys may well have had objective physical properties that distinguished them from control subjects. On the other hand, it is easy to see how retrospective distortion can be implicated in explaining these data.

Zucker et al. (1993c) reported physical attractiveness data on a group of boys with GID and clinical control boys. Color photographs of both groups of boys were taken at the time of assessment (mean age, 8.1 years). College students then made ratings of their pictures for five traits: attractive, beautiful, cute, handsome, and pretty. The raters were masked to group status, being informed only that they would be viewing pictures of boys. The boys with GID were rated as significantly more attractive than the clinical control boys on all five traits.

In a subsequent study, Fridell et al. (1996) reported physical attractiveness data on a group of girls with GID and clinical and nonclinical control girls (mean age, 6.6 years). College students rated the girls’ pictures for five traits: attractive, beautiful, cute, pretty, and ugly. On all traits except “ugly,” the girls with GID were rated as significantly less attractive than the clinical and nonclinical control girls. In a third study, boys with GID were judged to be significantly less “all-boy,” masculine, and rugged than control boys, whereas girls with GID were judged to be significantly more masculine, rugged, and tomboyish in appearance than control girls (McDermid et al. 1998).

The attractiveness/appearance data on boys complement and extend the previous findings of Stoller (1968b) and Green (1987). Nevertheless, interpretation of the data for both the boys and girls remains complex. On the one hand, these findings may reflect objective, biophysical differences in the appearance of GID and control children. On the other hand, they may reflect the effects of social shaping of physical appearance. In other words, physical appearance may be a predisposing factor in the development of GID or it may serve to perpetuate the disorder as a result of social shaping.

Handedness

Slightly more males than females show a preference for using the left hand in unimanual behavioral tasks such as writing. There is no established consensus for understanding the basis of this sex difference. Genetic factors clearly play a role in determining hand preference. Another line of research implicates adverse prenatal or perinatal events that result in an increase in left-handedness above the approximate gold standard of 10% in the general population.

Zucker et al. (2001) found that boys with GID (n=205) had a significantly elevated rate of left-handedness (19.5%) compared with three separate quasi-epidemiological samples of boys (11.8%, total n=13,253) and with a diagnostically heterogeneous sample of clinical control boys (8.3%, n=205). This finding parallels studies of adult males with GID, who also appear to have an elevated rate of left-handedness (e.g., Green and Young 2001; Herman-Jeglinska et al. 1997), as well as studies of adult men with a homosexual sexual orientation (Lalumière et al. 2000). At present, the explanation for the elevation remains unclear, but candidate factors have centered on some type of perturbation in prenatal development that in some way affects sex-dimorphic behavioral differentiation.

Sibling sex ratio and birth order

Boys with GID have an excess of brothers to sisters (sibling sex ratio) and have a later birth order (Blanchard et al. 1995; Zucker et al. 1997b). Some additional evidence shows that boys with GID are born later in relation to brothers but not to sisters. In the study by Blanchard and colleagues, clinical control boys showed no evidence for an altered sibling sex ratio or a late birth order. One biological explanation to account for these results pertains to maternal immune reactions during pregnancy. The male fetus is experienced by the mother as more “foreign” (i.e., antigenic) than the female fetus. Based on studies with lower animals, it has been suggested that one result of this is that the mother produces antibodies that have the consequence of demasculinizing or feminizing the male fetus but produce no corresponding masculinizing or defeminizing of the female fetus (Blanchard and Klassen 1997). This model predicts that males born later in a line of siblings might be more affected because the mother’s antigenicity increases with each successive male pregnancy, which is consistent with the empirical evidence on sibling sex ratio and birth order among GID probands. At present, however, this proposed mechanism has not been formally tested in humans.

Birth weight

On average, males weigh more than females at the time of birth (Arbuckle et al. 1993). There are, of course, many factors that influence variations in birth weight. One hypothesized factor is the sex difference in prenatal exposure to androgens. In one study, girls with CAH had a higher mean birth weight than unaffected girls (Qazi and Thompson 1971). In another study, genetic males with the complete form of the androgen insensitivity syndrome had comparable birth weights to genetic females (de Zegher et al. 1998).

Blanchard et al. (2002) compared the birth weights of boys with GID (n=250) and clinical control boys (n=739) and girls (n=261). The clinical control subjects showed the expected sex difference in birth weight. The boys with GID had birth weights that were intermediate to those of the clinical control boys and the control girls and did not differ significantly from either group. Further analysis of the birth weight data indicated an effect of sibling sex and birth order. The boys with GID who had two or more older brothers weighed significantly less at birth than did the control boys with two or more older brothers. In contrast, the GID and control boys with fewer than two older brothers did not differ in birth weight. Given the interactive effect of sibling sex and birth order, a simple prenatal hypoandrogenization influence among the GID probands is unlikely. Although it was speculative, Blanchard et al. (2002) suggested that the mechanism may be immunological, that is, that antimale antibodies produced by human mothers in response to immunization by male fetuses could decrease the birth weights of subsequent male children and could increase the odds of those children developing behavioral femininity (i.e., GID).

Biological mechanisms summary

Research conducted during the past decade has begun to identify some characteristics of children (particularly boys) with GID that may well have a biological basis. Corresponding studies of girls have been less numerous, largely because of problems in sample size that limit statistical power. In many respects it has been easier to rule out candidate biological explanations, such as the influence of gross anomalies in prenatal hormonal exposure, than it has been to identify the relevant biological mechanisms that are involved in affecting sex-dimorphic behavioral differentiation, but not sex-dimorphic genital differentiation. However, the identification of new potential biological markers may open up avenues for further empirical inquiry.

Psychosocial mechanisms

Several psychosocial factors have been thought to play a role in either the genesis or the perpetuation of GID. Most of these factors have been better studied in boys than in girls, and some of them have been held to be sex-specific. Below we discuss a few of the more prominent hypotheses.

Social reinforcement

Do parents shape or influence sex-dimorphic behavior in their children? This very simple question has proved exceedingly difficult to answer. If one turns to the normative literature, it becomes apparent how complicated the matter actually is (Fagot 1985; Fagot and Leinbach 1989; Lytton and Romney 1991; Ruble and Martin 1998). Perhaps a general conclusion is that parents do play a role in influencing patterns of sex-dimorphic behavior but not in the simplistic way that social learning theorists so readily expected.

When the parents of children with GID are asked to recall their initial responses to cross-gender behaviors, such as cross-dressing and cross-sex toy play, tolerance and nonresponsiveness appear to be very common, as suggested by reasonable evidence (Green 1987; J.N. Mitchell, unpublished doctoral dissertation, 1991; Zucker and Bradley 1995). Actual encouragement of these behaviors appears to be more common than negative or discouraging reactions.

Initial parental tolerance or encouragement of cross-gender behavior may therefore be of some etiological significance. The reasons for such tolerance appear to be quite variable, including parental values and goals regarding psychosexual development; feedback from professionals that the behavior is within normal limits and is only a phase; parental conflicts about issues of masculinity and femininity; and parental psychopathology and discord, which leave the parents relatively preoccupied and thus unresponsive to their child’s behavior.

Parental preference for sex of offspring

Some clinicians have suggested that parents’ tolerance of cross-gender behavior in boys is related to their preference for the sex of the child before its birth. Therefore, one line of empirical research has explored whether parents of boys with GID had disproportionately hoped that the child would be a girl. There was no evidence that this had occurred (Green et al. 1985; Zucker et al. 1994). However, Zucker and Bradley (1995) noted that among mothers of boys with GID who had desired daughters, a small subgroup appeared to experience what might be termed pathological gender mourning (Zucker et al. 1993a). The wish for a daughter was acted out (by cross-dressing the boy) or was expressed in other ways (see Zucker and Bradley 2000). These mothers often had severe depression, which was lifted only when the boy began to act in a certain feminine manner. This clinical observation, however, must be examined in much greater detail, including understanding how the wish for a girl, when it occurs, is resolved in most cases.

Mother–child and father–child relationships

In clinical studies of boys with GID, Stoller (1968b, 1975b, 1979) described an overly close relationship between mother and son and a distant, peripheral father–son relationship. Stoller (1985) claimed that such qualities were of etiological relevance: “The more mother and the less father, the more femininity” (p. 25). He argued that GID in boys was a “developmental arrest . . . in which an excessively close and gratifying mother-infant symbiosis, undisturbed by the father’s presence, prevents a boy from adequately separating himself from his mother’s female body and feminine behavior” (p. 25).

Green (1987) assessed the amount of shared time between parents of feminine boys and control subjects during the first 5 years of life. The fathers of feminine boys reported spending less time with their sons from the second to the fifth year than did the fathers of control subjects. In contradiction to the overcloseness hypothesis, the mothers of feminine boys also reported spending less time with their sons than did the mothers of control subjects.

The data on father–son shared time are quite consistent with a large body of clinical literature, whereas the mother–son data are not. Negative findings are difficult to interpret, particularly when they have not been consistently replicated. In this instance, they are difficult to reconcile with data showing that feminine boys feel closer to their mothers than to their fathers (Green 1987). Perhaps qualitative features of the mother–son relationship, such as attunement to each other’s feelings, would have been a more sensitive index of the nature of the dyad. It is also possible that relative time spent with mother versus father would have yielded differences between Green’s feminine boys and the control subjects.

Systematic studies on parent–child relationships have not yet been conducted for girls with GID. Preliminary clinical observations (Green 1974; Stoller 1975; Zucker and Bradley 1995) suggest that the mother–daughter relationship is often conflictual and not close, leading to what might be described as a disidentification from the mother (Greenson 1968). In some instances, femininity is devalued and masculinity is overvalued, which seem to be encouraged by the parents. Many of these girls tend to admire what their fathers do. In other cases, they appear to be quite frightened of their fathers and seem to develop the belief that they need to be quite strong and powerful to be safe. These preliminary clinical studies suggest that marked differences in the qualitative aspects of the parent–child relationship may exist between gender-disturbed boys and girls.

Maternal psychosexual development

Based on clinical data, Stoller (1968b) reported that the mothers of very feminine boys had childhood psychosexual conflicts. Although these women were initially feminine, he argued that “a degree of masculinity beyond what usually [would] be called tomboyishness” (p. 298) developed after a breach in the father–daughter relationship. A desire to be male was relinquished at puberty, yet socio-sexual experience was minimal, and, as adults, these women married distant men with whom sexual relations were poor. These women appeared to be uncomfortable with their femininity: “While these women have a feminine quality, inextricably woven in is this other, difficult to describe but easy to observe use of certain boyish or ‘neuter’ external features” (Stoller 1968b, p. 298).

Green’s effort to verify Stoller’s observations yielded mixed results. Mothers of feminine boys were more likely than mothers of control boys to describe themselves as tomboys (Green et al. 1985), but the mothers did not differ with regard to their recall of specific sex-typed behaviors (Green 1987). In a subsequent study using a factor-analyzed questionnaire, Zucker and Bradley (1995) did not find any differences in recalled childhood gender dysphoria or cross-gender behavior between mothers of boys with GID and clinical and nonclinical control mothers. In Green’s (1987) study, the two groups of mothers also did not differ with regard to the extent of adolescent sociosexual experience. Trait assessment of childhood masculinity and femininity did not provide strong support for the possibility that less severe signs of cross-gender behavior were present (Green 1987). Taken as a whole, these data suggest that mothers of very feminine boys, on average, do not have grossly atypical psychosexual histories. Perhaps other aspects of psychosexuality should be studied, such as the mother’s current attitude toward men and her concurrent views regarding masculinity and femininity.

General psychopathology

Little systematic study has been given to the presence of general dysfunction, such as psychiatric disorder and marital discord, in the parents of children with GID. However, the evidence to date suggests that these parents display more psychiatric and emotional difficulties than parents of control subjects (Marantz and Coates 1991; S.M. Wolfe, unpublished doctoral dissertation, 1990; Zucker and Bradley 1995, 2000). Assuming these preliminary data hold up, there will be two main questions to pursue. First, will there be any specificity to the parental difficulties, or will they simply be typical of what is observed in the parents of other children with psychiatric difficulties? Second, how, if at all, do these difficulties play a direct role in the development of the child’s GID? A rather simple hypothesis might be that the degree of parental dysfunction and marital discord is associated with tolerance of cross-gender behavior, perhaps because the parents are not functioning optimally and thus are less sensitive about developments in the child. If large enough samples could be generated, causal-modeling techniques could be used to test different hypothesized pathways leading to the development of GID in the child.

Treatment

Ethical issues

Any contemporary child clinician responsible for the therapeutic care of children and adolescents with GID will quickly be introduced to complex social and ethical issues pertaining to the politics of sex and gender in postmodern Western culture and will have to think them through carefully. Is GID really a disorder or is it just a normal variant of gendered behavior? Is marked cross-gender behavior inherently harmful or is it simply harmful because of social factors? If a teenager requests immediate cross-sex hormonal and surgical intervention as a therapeutic treatment for gender dysphoria, should the clinician comply? If parents request treatment for their child with GID to divert the probability of a later homosexual sexual orientation, what is the appropriate clinical response? All these questions force the clinician to think long and hard about theoretical and treatment issues.

Perhaps the most acute ethical issue concerns the relation between GID and a later homosexual sexual orientation. As noted below, follow-up studies of boys with GID, who were largely untreated, indicate that homosexuality is the most common long-term psychosexual outcome. Some parents of children with GID request treatment, in part, with an eye toward preventing subsequent homosexuality in their child, whether this is because of personal values, concerns about stigmatization, or other reasons.

In the 1990s, this rationale for treatment was subject to intense scrutiny (Minter 1999; Sedgwick 1991). Some critics, for example, have argued that clinicians, consciously or unconsciously, accept the prevention of homosexuality as a legitimate therapeutic goal (Pleak 1999). Minter (1999) has claimed, as have others (Scholinski 1997), that some adolescents in the United States are being hospitalized against their will because of their homosexual sexual orientation but under the guise of the GID diagnosis. To our knowledge, however, these allegations have not been verified in any systematic manner, and we are personally aware of no such case in which this has occurred (see also Meyer-Bahlburg 1999). Others have asserted, albeit without direct empirical documentation, that treatment of GID results in harm to children who are “homosexual” or “pre-homosexual” (Isay 1997). Lastly, some clinicians have raised questions about differential diagnosis, arguing that there is not always an adequate distinction between children who truly have GID and those who are merely pre-homosexual (Corbett 1996; Richardson 1996, 1999; cf. Zucker 1999a).

The various issues regarding the relation between GID and homosexuality are complex—both clinically and ethically. Three points, albeit brief, can be made. First, until it has been shown that any form of treatment for GID during childhood affects later sexual orientation, the issue is moot. From an ethical standpoint, however, the clinician has an obligation to inform parents about the state of the empirical database. Second, we have argued elsewhere that some critics incorrectly conflate gender identity and sexual orientation, regarding them as isomorphic phenomena (Zucker 1999b), as do some parents. Psychoeducational work with parents can review the various explanatory models regarding the statistical linkage between gender identity and sexual orientation (Bailey and Zucker 1995; Bem 1996), but also clarify their distinctness as psychological constructs. Third, many contemporary clinicians emphasize that the primary goal of treatment of children with GID is to resolve the conflicts that are associated with the disorder per se, regardless of the child’s eventual sexual orientation. Most clinicians who have worked with children and adolescents with GID believe that these youngsters experience a great deal of suffering—many of them are preoccupied with gender identity issues, they experience increased social ostracism and alienation as they get older, and they show evidence of other behavioral and psychiatric difficulties. Most clinicians, therefore, take the position that therapeutics designed to reduce the gender dysphoria, to decrease the degree of social ostracism, and to reduce the degree of psychiatric comorbidity constitute legitimate goals of intervention. How, then, might one go about reaching these therapeutic goals?

Developmental considerations

One aspect of the clinical literature suggests that there are important developmental considerations to bear in mind. For example, there is some evidence to suggest that GID is less responsive to psychosocial interventions during adolescence, and certainly by young adulthood, than it is during childhood. Therefore, the lessening of malleability and plasticity over time in gender identity differentiation is an important clinical consideration.

Treatment of children

For children with GID, clinical experience suggests that psychosocial treatments can be relatively effective in reducing the gender dysphoria. Therapeutic approaches have included the most commonly used interventions for children in general, including behavior therapy, psychodynamic therapy, parent counseling, and group therapy (for detailed reviews, see Zucker 1985, 1990, 2001). In considering these various therapeutic approaches, there is one important, sobering fact to contemplate: apart from a series of intrasubject behavior therapy case reports from the 1970s, one will find not a single randomized, controlled treatment trial in the literature (Zucker 2001). Therefore, the treating clinician must rely largely on the clinical wisdom that has accumulated in the case report literature and the conceptual underpinnings that inform the various approaches to intervention.

Treatment for children with GID often proceeds on two fronts: 1) individual therapy with the child, in which efforts are made to understand the factors that seem to fuel the fantasy of wanting to become a member of the opposite sex and then to resolve them; 2) parent counseling, in which efforts are made to help the child, in the naturalistic environment, to feel more comfortable about being a boy or a girl. Treatment can address several issues: for youngsters who are quite confused about their gender identity, one can focus on the mastery of basic cognitive concepts of gender, including correct identification of the self as a boy or a girl; encouragement in the development of same-sex friendships, in which areas of mutual interest can be identified; and exploration of factors within the family that might be contributing to the gender identity conflict.

With parents, treatment issues include the following: limit setting of cross-gender behavior and encouragement of gender-neutral or sex-typical activities; factors within the family matrix that may be contributing to the child’s gender identity conflict; and parent factors, including psychiatric impairment, that may be compromising functioning in the parental role in general.

Here we focus on some technical aspects of limit setting that are often misunderstood in the clinical literature and that therefore require further explication. A common error committed by some clinicians is to simply recommend to parents that they impose limits on their child’s cross-gender behavior without attention to context. This kind of authoritarian approach is likely to fail, just as it will with regard to any behavior, because it does not take into account systemic factors, both in the parents and in the child, that fuel the “symptom.” At the very least, a psychoeducational approach is required, but in many cases limit setting needs to occur within the context of a more global treatment plan.

From a psychoeducational point of view, one rationale for limit setting is that if parents allow their child to continue to engage in cross-gender behavior, the GID is in effect being tolerated, if not reinforced. Therefore, such an approach contributes to the perpetuation of the condition. Another rationale for limit setting is that it is in effect an effort to alter the GID from the “outside in,” whereas individual therapy for the child can explore the factors that have contributed to the GID from the “inside out.” At the same time that they attempt to set limits, parents also need to help their child with alternative activities that might help consolidate a more comfortable same-gender identification. Encouragement of same-sex peer group relations can be an important part of such alternatives; for example, some boys with GID develop an avoidance of male playmates because they are anxious about rough-and-tumble play and fantasy aggression. Such anxiety may be fueled by parent factors (e.g., where mothers conflate real aggression with fantasy aggression), but it may also be fueled by temperamental characteristics of the child (Zucker 2000a). Efforts on the part of parents to be more sensitive to their child’s temperamental characteristics may be quite helpful in planning peer group encounters that are not experienced by the child as threatening and overwhelming. It is not unusual to encounter boys with GID who have a genuine longing to interact with other boys, but because of their shy and avoidant temperament they do not know how to integrate themselves with other boys, particularly if they experience the contextual situation as threatening. Over time, with the appropriate therapeutic support, such boys are able to develop same-sex peer group relationships and begin to identify more with other boys as a result.

Another important contextual aspect of limit setting is to explore with parents their initial encouragement or tolerance of the cross-gender behavior. Some parents will tolerate the behavior initially because they have been told, or believe themselves, that the behavior is only a phase that their child will grow out of. Such parents become concerned about their child once they begin to recognize that the behavior is not merely a phase (Zucker 2000b). For other parents, the tolerance or encouragement of cross-gender behavior can be linked to some of the systemic and dynamic factors described earlier. In these more complex clinical situations, one must attend to the underlying issues and work them through. Otherwise, it is quite likely that parents will not be comfortable in shifting their position.

Although many contemporary clinicians have emphasized the important role of working with the parents of children with GID, one can ask if there is any empirical evidence demonstrating that this is effective. Again, systematic information on the question is scanty. The most relevant study (Zucker et al. 1985) found some evidence that parental involvement in therapy was significantly correlated with a greater degree of behavioral change in the child at 1-year followup, but this study did not make random assignment to different treatment protocols, so one has to interpret the findings with caution.

Treatment of adolescents

If GID in adolescence is not responsive to psychosocial treatment, should the clinician recommend the same kinds of physical interventions that are used with adults (Harry Benjamin International Gender Dysphoria Association 1998)? Before making such a recommendation, many clinicians will usually encourage adolescents with GID to consider alternatives to this invasive and expensive treatment. One area of inquiry can thus explore the meaning behind the adolescent’s desire for sex reassignment and whether there are viable alternative lifestyle adaptations. In this regard, the most common area of exploration pertains to the patient’s sexual orientation. Almost all adolescents with GID recall that they always felt uncomfortable growing up as boys or as girls, but that the idea of undergoing a sex change did not occur to them until they became aware of homoerotic attractions. For some of these youngsters, the idea that they might be gay or homosexual is abhorrent. For some such adolescents, psychoeducational work can explore their attitudes and feelings about homosexuality. Group therapy, in which such youngsters have the opportunity to meet gay adolescents, can be a useful adjunct in such cases. In some cases, the gender dysphoria will be resolved and a homosexual adaptation will ensue (Zucker and Bradley 1995). For others, however, a homosexual adaptation is not possible and the gender dysphoria does not abate.

For adolescents in whom the gender dysphoria appears to be chronic, the clinician can consider two main options: 1) management until the adolescent turns 18, when he or she then can be referred to an adult gender identity clinic; or 2) early institution of contrasex hormonal treatment. Regarding the latter option, Gooren and Delemarre-van de Waal (1996) recommended that one option with gender-dysphoric adolescents is to prescribe puberty-blocking luteinizing hormone-release agonists (e.g., depot leuprolide or depot triptorelin) that facilitate more successfully passing as the opposite sex. Thus, for example, in male adolescents, such medication can suppress the development of secondary sex characteristics, such as the growth of facial hair and deepening of the voice, which makes it more difficult to pass in the female social role. Cohen-Kettenis and van Goozen (1997, 1998) reported that early cross-sex hormone treatment for adolescents under age 18 years who are judged to be free of gross psychiatric comorbidity facilitates the complex psychosexual and psychosocial transition to living as a member of the opposite sex and results in a lessening of the gender dysphoria (see also Smith et al. 2001, 2002).

Although such early hormonal treatment is controversial (Cohen-Kettenis 1994, 1995; Meyenburg 1994, 1999), it may well be the treatment of choice once the clinician is confident that other options have been exhausted. One issue that is not yet resolved concerns determining who the best candidates for early hormonal treatments are. Cohen-Kettenis and van Goozen (1997) suggested that the least risky subgroup of adolescents with GID are those who show little evidence of psychiatric impairment (Smith et al. 2001). In our own clinic, a substantial majority of adolescents with GID would not qualify on this basis (Zucker et al. 2002). However, by adolescence, the issue is a tricky one because it is not clear to what extent the psychiatric impairment is a consequence of the chronic gender dysphoria (Newman 1970). A randomized controlled trial would be useful in resolving the matter.

Prognosis

Green (1987) has provided the most detailed information regarding long-term follow-up of boys with GID vis-à-vis gender identity and sexual orientation (for other follow-up reports, see Zucker and Bradley 1995). Green originally assessed 66 extremely feminine boys and 56 control boys at a mean age of 7.1 years (range, 4–12). About two-thirds of the boys in each of these groups were reevaluated at a follow-up mean age of 18.9 years (range, 14–24). A semistructured interview schedule was used to assess sexual orientation in fantasy and behavior. Using Kinsey scale criteria, all 35 reevaluated control boys were heterosexual in fantasy at follow-up. Of the 25 control boys who had experienced overt sexual relations, 1 was classified as bisexual, and the remainder were classified as heterosexual. In contrast, 33 of the 44 feminine boys (75%) were classified as either bisexual or homosexual; of the 30 feminine boys who had experienced overt sexual relations, 24 (80%) were classified as either bisexual or homosexual. Only 1 of the feminine boys, who was sexually attracted to males, was seriously entertaining the notion of sex-reassignment surgery. Thus, homosexuality rather than GID persisting into late adolescence or young adulthood appears to be the most common long-term outcome associated with GID.

Other more recent follow-up studies suggest a higher rate of persistent gender dysphoria. For example, Cohen-Kettenis (2001) reported that of 74 children with GID who had been initially assessed before age 12 (mean age, 9 years; range, 6–12) and had now reached adolescence 17 (23.0%) applied for sex-reassignment surgery. At present, then, it is clear that more information is needed regarding the natural history of GID, particularly when one starts with a prospective sample of children. Although homosexuality without co-occurring gender dysphoria is probably the most common outcome, heterosexuality appears to develop in a minority of youngsters, and persistent gender dysphoria occurs in others. A key research issue will be to attempt to identify predictors of these variations in outcome.

Research issues

The phenomenology of GID has now been well described. Excellent assessment tools are available for diagnostic workups (Green 1987; Zucker 1992; Zucker and Bradley 1995). Perhaps what needs to be better understood is the concept of gender dysphoria as it applies to young children, because it is this feeling state that is the sine qua non of its expression during adulthood.

The psychobiology of gender identity, gender role, and sexual orientation remains an area of intense study. The exact effects of prenatal sex hormones on postnatal sex-dimorphic behavior will continue to be an area of great importance. More recent studies, particularly in relation to sexual orientation, may yield new insights regarding the role of biological phenomena. These domains of research include molecular genetics (Hamer et al. 1993; Hu et al. 1995; see also Rice et al. 1999), behavior genetics (Mustanski et al. 2002), cognitive abilities and neuropsychological function (reviewed in Zucker and Bradley 1995), neuroanatomical structures (Allen and Gorski 1992; Byne et al. 2001; LeVay 1991; Zhou et al. 1995), dermatoglyphics (e.g., Brown et al. 2002; Hall and Kimura 1994; Williams et al. 2000), and the demographic variables of sibling sex ratio and birth order (Blanchard and Bogaert 1996; Blanchard and Sheridan 1992; Blanchard et al. 1996). Much of this research has focused on sexual orientation per se, so its precise relevance for GID in children is unclear. Elsewhere, Zucker and Bradley (1995) examined the evidence for convergence and divergence in the biological studies of sexual orientation and GID.

Psychosocial research has also yielded important leads. It is now clear how complex early social interaction is with regard to gender (Fagot and Leinbach 1989). Microsocial observations of the behavior of children with GID may help to elucidate the complexities in early interactions with significant others. The assessment of general psychopathology, in both the child and the parents, requires greater attention. Elucidating how general psychopathology serves as a risk factor in this disorder will be of great importance. Finally, the connection between GID and later sexual orientation suggests that a better understanding of the development of eroticism is required in its own right (Bailey and Zucker 1995). To date, the processes underlying erotic development have not been well described (Bem 1996; Green 1987). It is hoped that advances on all of these fronts will sharpen our understanding of psychosexual differentiation and its disorders as we begin the third millennium.

|

Table 1. DSM-IV-TR Diagnostic Criteria for Gender Identity Disorder

|

Table 2. DSM-IV-TR Diagnostic Criteria for Gender Identity Disorder Not Otherwise Specified

|

Table 3. DSM-IV-TR Diagnostic Criteria for Transvestic Fetishism

|

Table 4. DSM-IV-TR Diagnostic Criteria for Sexual Disorder Not Otherwise Specified

Achenbach TM, Edelbrock CS: Behavioral problems and competencies reported by parents of normal and disturbed children aged four through sixteen. Monogr Soc Res Child Dev 46(1):1–82, 1981Crossref, Google Scholar