Relationship of Variability in Residual Symptoms With Recurrence of Major Depressive Disorder During Maintenance Treatment

Abstract

Objective: To investigate how residual symptoms from an index episode of major depressive disorder may be associated with recurrence, the authors conducted a trial involving four maintenance treatment approaches and examined 1) whether the level and variability of residual symptoms differed among the maintenance treatment conditions and 2) whether greater symptom variability is associated with a higher likelihood of recurrence and more rapid recurrence. Method: Patients enrolled in a maintenance treatment study (N=114) were randomly assigned to one of four maintenance treatment conditions: imipramine plus interpersonal psychotherapy, imipramine alone, interpersonal psychotherapy alone, or no active treatment. Residual symptoms were characterized both as continuous variables (mean values and coefficients of variation for Hamilton Depression Rating Scale and Global Assessment Scale [GAS] scores) and as a categorical variable, the percentage of maintenance evaluations with a Hamilton depression scale score ≥8 (e.g., with a symptom peak). Results: Analysis of variance revealed no differences among the four treatment conditions in patients’ levels of residual symptoms or symptom variability assessed as a continuous variable, but patients in the combined treatment group had fewer symptom peaks, compared to those in the placebo and interpersonal psychotherapy groups. Cox proportional hazards modeling showed that higher coefficients of variation for both the Hamilton depression scale and the GAS scores and a greater percentage of evaluations with symptom peaks were associated with shorter survival times. Conclusions: A higher level of symptom variability during maintenance treatment is associated with higher risk for recurrence of depression and may provide a specific target for maintenance treatments.

Over the last 20 years increasing focus has been placed on continuation and maintenance treatment of depression (1–3), and parameters have been adopted for defining relapse and recurrence (4). Treatments for these empirically defined features of the natural history of depression have also been described (1, 5–7). Most studies have used dichotomous measures of acute treatment outcome defined by symptoms on the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (8), Beck Depression Inventory (9), and the Global Assessment Scale (GAS) (10). However, some level of symptoms often persists even after a patient has been determined to be “well,” according to scores on these measures. This phenomenon may be related to both the varied natural history and the multifactorial etiology of depression, which includes biological predispositions (11), vulnerable cognitive processes (12), and environmental stressors such as significant life events and long-term stressors (13). Indeed, Paykel (14) noted, “Failure to remit, delayed remission, partial remission with considerable residual symptoms, relapse and recurrence are common outcomes of the depressive illness.” The subclinical nature of persistent symptoms may not warrant a diagnosis of either an incompletely treated or new episode of major depression, of dysthymic disorder, or of personality disorder. Nonetheless, residual symptoms may continue to cause significant subjective distress (15) and may, in fact, be risk factors for subsequent episodes of depression (14).

The purpose of this report is to extend previous findings by describing the quality of remission with different maintenance treatments in a group of patients with recurrent depression. We also sought to determine whether recurrence of depression was related to the level or variability of persistent symptoms during maintenance treatment. The studies mentioned earlier defined residual symptoms as depression severity or global functioning symptoms in excess of the threshold criterion for recovery. In this study, we examined residual symptoms in two ways: first, on a continuous scale of symptom severity and variability and, second, on the basis of a threshold criterion for symptom exacerbations (symptom peaks). We hypothesized that 1) the level and variability of residual symptoms would differ among four maintenance treatment conditions (medication, maintenance interpersonal psychotherapy, medication plus maintenance interpersonal psychotherapy, and placebo) and 2) patients with greater variability in depression and global functioning ratings would experience more rapid recurrences during maintenance treatment.

Method

Patients

Methods and study design have been described in detail elsewhere (1) but will be briefly reviewed. The original protocol from which the subjects were drawn was designed to explore the relative efficacy of five maintenance treatment strategies in preventing or delaying recurrences in a group of patients with high rates of recurrence of unipolar depression (1, 6). To enter the original protocol, subjects between ages 21 and 65 years were required to have a minimum of a 10-week remission period between the index episode and the immediately prior episode, according to Research Diagnostic Criteria (RDC) (16). A minimum Hamilton depression scale score of 15 and a minimum score of 7 on the Raskin Severity of Depression Scale (17) were also required for study participation. Eligible patients were then evaluated with the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia (18). Patients who met both the RDC for a major depressive episode and the historical requirements for previous episodes and clear remissions were entered into the protocol. After complete description of the study to the subjects, written informed consent was obtained.

Before entering the maintenance phase of the study, all patients (N=230) received acute treatment consisting of a combination of imipramine hydrochloride (150–300 mg/day) and interpersonal psychotherapy (19). Treatment sessions were scheduled weekly for 12 weeks, then biweekly for 8 weeks, and then monthly. After achieving a Hamilton depression scale score ≤7 and a Raskin Severity of Depression Scale score ≤5 for 3 consecutive weeks in acute treatment, patients entered the continuation phase of the study, which lasted an additional 17 weeks. To remain in the continuation phase of treatment, patients were required to have stable Hamilton depression scale and Raskin Severity of Depression Scale scores and a stable imipramine dose. At the patients’ entrance into the continuation phase, their personality pathology was assessed with the Personality Assessment Form (20). At the end of the 17 weeks, symptomatically stable patients were evaluated once again with the Personality Assessment Form and were randomly assigned to one of five maintenance treatments for a period of 3 years or until they experienced a recurrence of illness. The original five treatments were 1) a maintenance form of interpersonal psychotherapy (21, 22) offered alone, 2) maintenance interpersonal psychotherapy with active imipramine therapy continued at the acute treatment dose, 3) maintenance interpersonal psychotherapy with placebo, 4) medication clinic visits with active imipramine therapy, and 5) medication clinic visits with placebo.

For the purposes of the present report, we combined two of the treatment groups, both of which received maintenance interpersonal psychotherapy as the primary modality of treatment. All previous analyses found these groups to be equivalent. Thus, the four treatments we compared were 1) medication clinic visits with placebo (N=19), 2) medication clinic visits with active imipramine therapy (N=23), 3) maintenance interpersonal psychotherapy alone or with placebo (N=47), and 4) maintenance interpersonal psychotherapy with active imipramine therapy continued at the acute treatment dose (N=25). During maintenance therapy, patients had monthly contact with their assigned therapist and psychiatrist. Of the 128 patients who ultimately entered the maintenance therapy phase and were followed for 3 years, 114 met the additional requirement for this report of having at least two office contacts with their treatment team and two independent evaluators during the maintenance phase. Of the 14 patients who did not meet this criterion, 11 experienced a recurrence, and three were dropouts (one found the clinic schedule inconvenient, one was nonadherent with medication treatment, and one died in a house fire). Among the 14 patients who were not included, five were receiving interpersonal psychotherapy alone or interpersonal psychotherapy with placebo, five were receiving active medication therapy alone, and four were receiving placebo. All of the patients who were receiving maintenance interpersonal psychotherapy with active imipramine therapy had at least two office contacts during maintenance therapy. If a patient presented with substantial clinical worsening or called the clinic to report such worsening, the clinician evaluated the patient twice during a 7-day period. Onset of a recurrence of depression during maintenance therapy was identified by agreement of two evaluators—an independent clinical evaluator and a senior psychiatrist not affiliated with the study—who determined that the patient met the criteria for an episode of major depression. For patients with recurrence of depression, the last two Hamilton depression scale scores, which contributed to the identification of recurrence, were not included in the current analyses, because inclusion of these scores would have artificially increased the level and variability of symptoms.

Statistical methods

The time spent in maintenance treatment for these 114 patients was compared across the four treatment groups by using Cox proportional hazards analysis. This analysis was performed primarily to confirm our previous findings about the treatments’ efficacy in preventing recurrences (1).

To determine the effect of residual symptom severity and variability on recurrence, we first examined these measures as continuous variables. The mean, standard deviation, and coefficient of variation of the Hamilton depression scale and GAS scores during maintenance treatment were determined for each patient. The coefficient of variation expresses the standard deviation of the individual’s score as a percentage of the mean (coefficient of variation=standard deviation/mean × 100). This measure is useful for examining the size of the variation relative to the size of the observation and also allows for independence from the units of observation. Mean values for each measure were compared across treatment groups with analysis of variance (ANOVA).

The risk of recurrence as a function of residual symptom level and variability was determined by Cox proportional hazards analysis with a stepwise selection model. Treatment assignment, which had been shown to influence recurrence rates, was entered first into the model. Residual symptom levels and variability were entered next and were considered to be significant if the coefficient was associated with a probability of <0.05. Hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) are reported for the variables in the models.

In the second type of analysis, we considered the percentage of Hamilton depression scale scores ≥8 (symptom peak) during maintenance treatment. We selected this level because Hamilton depression scale scores ≤7 were used to define recovery. A t test was performed to compare data for patients with and without symptom peaks to determine if there was a difference in total number of contacts with clinicians during maintenance treatment. This type of analysis parallels those reported by Paykel et al. (23) and focuses on the amount of time spent above a predefined criterion level of symptom severity. ANOVA was used to contrast the percentage of maintenance treatment scores ≥8 among the four maintenance treatment groups. We used Cox proportional hazards modeling, as described earlier, to determine the effect of the number of symptomatic peaks on recurrence.

Finally, we examined scores for each item of the Hamilton depression scale to determine if some items had a greater degree of variability and therefore had greater influence on overall symptom variability. This analysis was done by dividing the observed range of scores for each item by the possible range of scores for that item in each subject, and then calculating the group mean.

Results

The demographic and clinical characteristics of the 128 patients entering the maintenance phase of treatment have been described elsewhere (1). Among the 114 subjects included in our analyses, the four treatment groups (measured at baseline) were equivalent with respect to age, Raskin Severity of Depression Scale score, 17-item and 25-item Hamilton depression scale score, and GAS score at entry into the study. The groups were also similar in duration of the index episode, number of previous episodes, and age at onset of first depressive episode (Table 1).

Statistically significant differences in time to recurrence were found among the four groups, as determined by Cox proportional hazards analysis (p≤0.0001). The results are similar to those of our previous study (1), in which we found that patients who received imipramine as part of their treatment regimen experienced longer recurrence-free intervals. We note these findings simply to illustrate the difference in time to recurrence among the four treatment modalities.

Recurrence of depression

Continuous definition of symptom severity and variability.

To identify differences in the quality of remission among the groups, we used ANOVA to compare the mean, standard deviation, and coefficient of variation of the Hamilton depression scale and GAS scores. There were no statistically significant differences among the treatment groups with respect to level or variability of residual symptoms (Table 2).

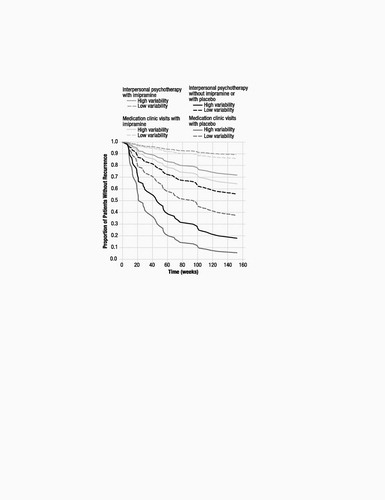

Relative to survival time for the placebo group, survival time was significantly higher for the combined treatment group (hazards ratio=0.15, 95% CI=0.06–0.41, p=0.0002) and the imipramine only group (hazards ratio=0.12, 95% CI=0.04–0.35, p=0.0002) but not for the interpersonal psychotherapy only group (hazards ratio=0.59, 95% CI=0.30–1.16, p=0.13). Cox proportional hazards modeling was used to examine the length of time to recurrence in relation to symptom variability. This analysis, which utilized stepwise selection and included the four treatment groups in the model, indicated that higher coefficients of variation for both the Hamilton depression scale (relative risk=1.01, 95% CI=1.00–1.02, p≤0.05) and the GAS (relative risk=1.154, 95% CI=1.08–1.23, p≤0.0001) were significantly associated with lower survival times. No additional variables met the 0.05 significance level for entry into the model. The difference between groups in mean scores was not significant for the Hamilton depression scale (χ2=0.64, df=1, p=0.43) or the GAS (χ2=0.34, df=1, p=0.56). The difference between the standard deviations for the Hamilton depression scale (χ2=2.68, df=1, p=0.10) and the GAS (χ2<0.01, df=1, p=0.95) was also not significant. Figure 1 shows a graphical display of the results of a Cox regression analysis of predicted survival curves for low and high levels of variability for each treatment, as determined by the 25th and 75th percentiles of the coefficients of variation for the Hamilton depression scale and GAS scores. Subjects with low variability had a longer survival course for each of the treatments, compared to their respective high-variability counterparts within that treatment group.

Categorical definition of residual symptom variability.

Before performing similar analyses on the categorical (symptom peak) data, we used a t test to determine if there was a difference in the number of recorded Hamilton depression scale scores between patients who did not experience any symptom peaks and patients who had one or more symptom peaks. This analysis was done to confirm that patients who had at least one symptom peak were not underrepresented in the analysis because of early relapse or dropout. No difference was found in the number of Hamilton depression scale scores between the patients with no symptom peaks and those with one or more symptom peaks (t=−0.66, df=112, p=0.51).

Treatment group was significantly related to outcome. Relative to survival time for the placebo group, survival time was significantly higher for the combined treatment group (hazard ratio=0.20, 95% CI=0.07–0.53, p=0.001) and the imipramine only group (hazard ratio=0.14, 95% CI=0.05–0.43, p=0.0006) and was nonsignificantly higher for the interpersonal psychotherapy only group (hazard ratio=0.57, 95% CI=0.30–1.09, p=0.09).

To identify differences in the quality of remission among the groups according to the categorical model, ANOVA was used to compare the percentage of Hamilton depression scale scores ≥8 across the four groups. A statistically significant difference between the groups was identified (F=3.27, df=3, 110, p<0.03). Post hoc tests revealed a significantly lower percentage of symptom peaks in the combination treatment group, compared to the placebo and interpersonal psychotherapy only groups. Given the waxing and waning nature of these symptom peaks, we feel they represent a true measure of variability.

Cox proportional hazards modeling was again used to examine the relationship between symptom peaks and time to recurrence. This analysis, which used stepwise selection and included the four treatment groups in the model, indicated that an increased percentage of symptom peaks during maintenance treatment was significantly associated with decreased survival time (relative risk=1.02, 95% CI=1.01–1.03, p≤0.005).

Clinical correlations

We computed correlation coefficients between the values for the patients’ demographic and clinical characteristics and the coefficients of variation of the Hamilton depression scale and GAS scores. None of these variables was significantly correlated with either coefficient of variation. We also examined correlations of the scores on the Personality Assessment Form at recovery with the coefficients of variation and standard deviations. This analysis was done for the total Personality Assessment Form score as well as for the scores on the three dimensions of the Personality Assessment Form: odd/eccentric, dramatic, and anxious/fearful personality subtypes. Earlier studies showed good stability between continuation and premaintenance evaluations for the clinician-rated Personality Assessment Form, with correlation coefficients ranging from 0.56 to 0.89 for specific diagnoses and even higher correlations for the three clusters (24). Our analysis revealed a significant correlation between the Personality Assessment Form total score and the standard deviation of the Hamilton depression scale scores (r=0.23, df=111, p<0.02). We also found statistically significant correlations with the standard deviation of the Hamilton depression scale score for both cluster B (dramatic) (r=0.20, df=111, p<0.03) and cluster C (anxious/fearful) (r=0.25, df=111, p<0.008) scores. In other words, personality disorder features were positively associated with variability in Hamilton depression scale scores.

Descriptive analysis

Finally, we performed a descriptive analysis for each item of the Hamilton depression scale to determine which items showed the greatest variability during maintenance treatment. For each patient, the observed range of scores for each item was divided by the possible range; and the mean for this value across all patients was then calculated. The seventeen items of the Hamilton depression scale are listed in descending order of variability in Table 3. The items with the greatest variability were anergia; loss of libido; initial, middle, and delayed insomnia; psychological and somatic anxiety; depressed mood; and weight loss.

Discussion

We were interested in determining whether the level of variability of Hamilton depression scale and GAS scores was related to the type of maintenance treatment and whether variability influenced time to recurrence in patients with recurrent major depressive disorder. Our findings show that the four treatment conditions we studied differed in terms of the percentage of residual symptom peaks, but they did not differ in terms of residual symptoms considered on a continuous scale. Second, compared with patients who remained well, patients who had recurrences had higher levels of symptoms and greater symptom variability, illustrated by an increase in percentage of symptom peaks. Third, we found that a higher coefficient of variation for both the Hamilton depression scale and the GAS scores was associated with significantly shorter survival time. Finally, a higher level of symptom variability was related to higher levels of personality pathology. These findings suggest that, independent of the type of treatment that a patient is receiving, a higher level of variability of depressive symptoms and functioning are associated with a higher risk of recurrence.

The findings of minor differences in residual symptoms among the four treatment conditions is somewhat surprising because there was a dramatic difference in survival among the four groups (1), i.e., the groups treated with active medication remained well significantly longer than their nonmedicated counterparts. This finding would lead one to predict that the quality as well as the “quantity” (i.e., survival time) of the weeks spent in maintenance therapy would also be superior for the more aggressively treated groups. The patients who received the combination of imipramine and interpersonal psychotherapy had fewer symptom peaks than the patients who received placebo or interpersonal psychotherapy alone, but the groups did not differ when residual symptoms were defined by standard deviation, coefficient of variation, or mean level. Thus, the specific effect of pharmacotherapy on residual symptoms appears to be small. However, it is possible that active medication treatment stabilized those symptoms that were more variable, i.e., the neurovegetative symptoms. Psychological therapies may not adequately address these features of recurrent depression, and this lack of adequate effects may have resulted in the differences in symptom peaks. It should be noted that all of the patients who received combination maintenance interpersonal psychotherapy and imipramine had at least two office contacts during maintenance therapy. This pattern of office contacts is in contrast to those of the other three treatment groups, which each had an equal number of subjects excluded from this analysis because they either had a recurrence or dropped out. Thus, the combination of psychotherapy and active medication or of not changing the treatment regimen (all patients received combination therapy in the acute and continuation phases) on the number of symptom peaks may protect patients against early relapse as well as recurrence.

It is likely that factors other than random treatment assignment were more strongly related to symptom variability during maintenance treatment. As discussed later in this section, personality features may be one such factor. Higher levels of symptom variability may also be a trait that is present only in certain individuals, as suggested by the absence of treatment group differences in variability. An alternate hypothesis is that different treatment conditions may produce different sources of symptom variability, which nonetheless lead to the same outcome, recurrence. For example, earlier reports have shown that interpersonal psychotherapy patients who had a recurrence tended to be less able to focus on interpersonal themes during therapy (21, 22, 25), whereas imipramine treated patients who had a recurrence tended to have poorer medication compliance (26).

There is a large body of evidence concerning the chronicity of major depression (27–32), and the literature describing residual symptoms of depression and their clinical significance continues to grow. Studies published by Fava and colleagues (33, 34), Judd et al. (35, 36), and other thought leaders in this area (37) have found that patients with residual subthreshold depressive symptoms during recovery had significantly more severe and chronic future courses of depression.

Paykel et al. (23) also examined residual symptoms after partial remission from depression. The only significant predictor of residual symptoms in that study was a more severe initial illness. However, residual symptoms were strong predictors of early relapse, which occurred in 76% (13 of 17 patients) of those with residual symptoms and 25% (10 of 40 patients) of those without residual symptoms. Paykel et al. did not examine the effect of different treatments on level of residual symptoms. In practical terms, recovered patients with more variability in symptoms, especially neurovegetative symptoms, may need closer surveillance for relapses or recurrences.

Frank et al. (5) analyzed the quality of remission during the continuation phase of treatment in the same patient group described in this paper. Eighty-one (63%) of the 128 patients never experienced a Hamilton depression scale score >9 during the 20-week continuation period. Twenty-six patients (20%) experienced at least one symptomatic “blip” (Hamilton depression scale score >10), and 21 patients (16%) experienced two or more blips. While Frank et al. found these residual symptoms (blips) to be related to poor treatment outcome during the continuation phase of treatment, we found residual symptoms (defined as both increased symptom variability and increased percentage of blips during maintenance therapy) to be a risk factor for disease recurrence during maintenance treatment. This finding reinforces the potential importance of the relationship between residual symptoms and outcome during different phases of depression treatment. In addition, this finding is supported by a recent meta-analysis by Geddes et al. (38), who found that continuing treatment with antidepressants reduces the risk of relapse by 70%, compared with treatment discontinuation, and appears to benefit many patients with recurrent depressive disorder.

Our results showed a statistically significant correlation between the standard deviation of the Hamilton depression scale score and cluster B, cluster C, and total scores on the Personality Assessment Form. Other studies have examined the relationship between personality pathology and time to remission (24, 39, 40). Personality traits and disorders, long a controversial variable with respect to the etiology of depression and its failed treatment, may play a significant role in residual symptoms (41, 42). For example, “character spectrum disorder,” identified by Akiskal (41), is marked by unstable traits such as dependent, histrionic, antisocial, and schizoid features, as well as irritable dysphoria and substance abuse, and is thought to be secondary to unstable and chaotic developmental experiences. In patients with character spectrum disorder, depression is viewed as secondary to personality pathology and is, in fact, distinct from true affective disorder. The traits identified by Akiskal were largely replicated in our study: specifically cluster B (dramatic) and cluster C (anxious/fearful) scores on the Personality Assessment Form were significantly associated with the standard deviation of the Hamilton depression scale score, and the standard deviation of the Hamilton depression scale score was in turn a significant risk factor for recurrence. One limitation of our study is that patients with severe clinical features of personality disorders, particularly cluster A and B disorders, were excluded from study participation.

The limitations of the current study include the post hoc nature of the analyses, the limited temporal resolution of symptom measures, and the fact that subjects with the most rapid recurrence (e.g., less than two office visits) were not included. It should also be remembered that patients were seen only once a month unless symptoms appeared, and thus some symptom peaks may have been missed. In addition, the size of the observed effects for symptom variability on recurrence was modest. Finally, it should be noted that the medication used in the study, imipramine, is not currently a first-line choice of antidepressant. It would be ideal to replicate this study with a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor or a newer dual-mechanism antidepressant to see if outcomes or tolerability were comparable. Nevertheless, our findings suggest that variability of residual symptoms, as well as the actual level of residual symptoms, may constitute a new target for the maintenance treatment of recurrent depression. In addition, while a literature about subsyndromal symptomatic depression exists (43, 44), there has been no research to our knowledge on residual symptoms during an index episode. While these two phenomena are related across the spectrum of depressive illnesses, our findings suggest that minimizing the variability of residual symptoms during maintenance treatment may help to prevent recurrences.

| Patients ReceivingMedication Clinic Visits | Patients ReceivingInterpersonal Psychotherapy | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| With Placebo (N=19) | With Imipramine (N=23) | Without Imipramine or With Placebo (N=47) | With Imipramine (N=25) | Analysis | ||||||

| Characteristic | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | F (df=3, 110) | P |

| Age (years) | 40.3 | 12.0 | 37.3 | 10.5 | 40.9 | 10.8 | 40.8 | 11.4 | 0.61 | 0.61 |

| Raskin Severity of Depression Scale score | 10.4 | 2.0 | 10.5 | 1.8 | 10.2 | 1.9 | 10.1 | 1.8 | 0.20 | 0.90 |

| Hamilton Depression Rating Scale score | ||||||||||

| 17-item scale | 22.6 | 5.2 | 21.0 | 4.7 | 21.5 | 4.6 | 21.7 | 4.9 | 0.41 | 0.75 |

| 25-item scale | 26.1 | 6.1 | 25.4 | 5.5 | 26.8 | 5.4 | 26.6 | 5.9 | 0.29 | 0.83 |

| Global Assessment Scale score | 49.5 | 6.7 | 48.3 | 9.4 | 50.4 | 8.0 | 48.8 | 8.7 | 0.40 | 0.76 |

| Duration of index episode (weeks) | 24.6 | 21.9 | 26.0 | 15.9 | 24.3 | 19.2 | 21.6 | 20.0 | 0.21 | 0.89 |

| Number of previous episodes | 4.6 | 3.0 | 6.4 | 4.8 | 7.7 | 8.6 | 8.4 | 10.0 | 1.07 | 0.36 |

| Age at first depressive episode (years) | 27.4 | 10.6 | 23.3 | 7.8 | 28.9 | 11.5 | 25.5 | 9.6 | 1.73 | 0.17 |

| Patients ReceivingMedication Clinic Visits | Patients ReceivingInterpersonal Psychotherapy | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| With Placebo (N=19) | With Imipramine (N=23) | Without Imipramine or With Placebo (N=47) | With Imipramine (N=25) | Analysis | ||||||

| Characteristic | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | F (df=3, 110) | P |

| 17-item Hamilton Depression | ||||||||||

| Rating Scale score | ||||||||||

| Mean | 6.0 | 3.5 | 4.9 | 2.7 | 5.9 | 3.5 | 4.2 | 2.0 | 1.81 | 0.15 |

| Standard deviation | 4.2 | 1.5 | 3.7 | 2.1 | 3.8 | 1.5 | 3.4 | 1.5 | 0.80 | 0.49 |

| Coefficient of variationa | 84.5 | 31.5 | 88.7 | 44.9 | 77.2 | 31.0 | 89.4 | 30.6 | 0.21 | 0.89 |

| Global Assessment Scale score | ||||||||||

| Mean | 80.8 | 7.1 | 81.9 | 5.9 | 80.6 | 6.9 | 82.9 | 3.5 | 0.63 | 0.60 |

| Standard deviation | 8.6 | 4.4 | 8.2 | 4.4 | 8.2 | 2.8 | 7.8 | 3.2 | 0.48 | 0.70 |

| Coefficient of variationa | 11.0 | 6.2 | 10.4 | 6.4 | 10.4 | 4.4 | 9.6 | 4.1 | 0.59 | 0.62 |

| Rank | Item Number | Item | Mean Range of Scores | Possible Range of Scores | Mean Range/Possible Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 13 | Anergia | 1.18 | 2 | 0.59 |

| 2 | 14 | Loss of libido | 1.15 | 2 | 0.58 |

| 3 | 4 | Initial insomnia | 1.13 | 2 | 0.57 |

| 4 | 5 | Middle insomnia | 1.12 | 2 | 0.56 |

| 5 | 6 | Delayed insomnia | 1.01 | 2 | 0.51 |

| 6 | 10 | Psychological anxiety | 2.02 | 4 | 0.51 |

| 7 | 11 | Somatic anxiety | 2.02 | 4 | 0.51 |

| 8 | 1 | Depressed mood | 2.00 | 4 | 0.50 |

| 9 | 17 | Weight loss | 0.92 | 2 | 0.46 |

| 10 | 7 | Work and interest | 1.68 | 4 | 0.42 |

| 11 | 2 | Guilt feelings | 1.38 | 4 | 0.34 |

| 12 | 12 | Loss of appetite | 0.66 | 2 | 0.33 |

| 13 | 9 | Agitation | 1.00 | 4 | 0.25 |

| 14 | 8 | Retardation | 0.97 | 4 | 0.24 |

| 15 | 3 | Suicide | 0.73 | 4 | 0.18 |

| 16 | 15 | Hypochondriasis | 0.61 | 4 | 0.15 |

| 17 | 16 | Loss of insight | 0.05 | 2 | 0.03 |

Figure 1. Cox Proportional Hazards Analysis Predicting the Proportion of Patients Without Recurrence of Major Depressive Disorder in Four Maintenance Treatment Conditions, by Low and High Levels of Symptom Variabilitya

a Low symptom variability was indicated by coefficients of variation below the 25th percentile (coefficients of variation of 61 for the Hamiltion Depression Rating Scale and 7 for the Global Assessment Scale [GAS]); high symptom variability was indicated by coefficients of variation above the 75th percentile (coefficients of variation of 99 for the Hamilton depression scale and 12 for the GAS).

1 Frank E, Kupfer DJ, Perel JM, Cornes C, Jarrett DB, Mallinger AG, Thase ME, McEachran AB, Grochocinski VJ: Three-year outcomes for maintenance therapies in recurrent depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1990; 47: 1093–1099Crossref, Google Scholar

2 Lavori PW, Dawson R, Mueller TB: Causal estimation of time-varying treatment effects in observational studies: application to depressive disorder. Stat Med 1994; 13:1089–1100Crossref, Google Scholar

3 Prien RF, Kupfer DJ, Mansky PA, Small JG, Uason VB, Voss CB, Johnson WE: Drug therapy in the prevention of recurrences in unipolar and bipolar affective disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1984; 41:1096–1104Crossref, Google Scholar

4 Frank E, Prien RF, Jarrett RB, Keller MB, Kupfer DJ, Lavori PW, Rush AJ, Weissman MM: Conceptualization and rationale for consensus definitions of terms in major depressive disorder: remission, recovery, relapse, and recurrence. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1991; 48:851–855Crossref, Google Scholar

5 Frank E, Kupfer DJ, Levenson J: Continuation therapy for unipolar depression: the case for combined treatment, in Combined Pharmacotherapy and Psychotherapy for Depression. Edited by Manning DM, Frances AJ. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1990, pp 135–149Google Scholar

6 Frank E, Kupfer DJ: Maintenance treatment of recurrent unipolar depression: pharmacology and psychotherapy, in Chronic Treatments in Neuropsychiatry. Edited by Kemali D, Racagni G. New York, Raven Press, 1985, pp 139–151Google Scholar

7 Klerman GL, DiMascio A, Weissman M, Prusoff B, Paykel ES: Treatment of depression by drugs and psychotherapy. Am J Psychiatry 1974; 131: 186–191Crossref, Google Scholar

8 Hamilton M: A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1960; 23:56–62Crossref, Google Scholar

9 Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J: An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1961; 4: 561–571Crossref, Google Scholar

10 Endicott J, Spitzer RL, Fleiss JL, Cohen J: The Global Assessment Scale: a procedure for measuring overall severity of psychiatric disturbance. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1976; 33:766–771Crossref, Google Scholar

11 Kupfer DJ, Frank E, McEachran AB, Grochocinski VJ: Delta sleep ratio: a biological correlate of early recurrence in unipolar affective disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1990; 47:1100–1105Crossref, Google Scholar

12 Beck AT: Depression: Causes and Treatment. Philadelphia, University of Pennsylvania Press, 1967Google Scholar

13 Brown GW, Bifulco A, Harris T, Bridge L: Life stress, chronic subclinical symptoms and vulnerability to clinical depression. J Affect Disord 1986; 11:1–19Crossref, Google Scholar

14 Paykel ES: Historical overview of outcome of depression. Br J Psychiatry Suppl 1994; 26:6–8Google Scholar

15 Judd LL, Akiskal HS, Maser JD, Zeller PJ, Endicott J, Coryell W, Paulus MP, Kunovac JL, Leon AC, Mueller TI, Rice JA, Keller MB: A prospective 12-year study of subsyndromal and syndromal depressive symptoms in unipolar major depressive disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1998; 55:694–700Crossref, Google Scholar

16 Spitzer RL, Endicott J, Robins E: Research Diagnostic Criteria: rationale and reliability. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1978; 35:773–782Crossref, Google Scholar

17 Raskin A, Schulterbrandt J, Reatig N, McKeon JJ: Replication of factors of psychopathology in interview, ward behavior and self-report ratings of hospitalized depressives. J Nerv Ment Dis 1969; 148:87–98Crossref, Google Scholar

18 Endicott J, Spitzer RL: A diagnostic interview: the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1978; 35:837–844Crossref, Google Scholar

19 Klerman GL, Weissman MM, Rounsaville BJ, Chevron E: Interpersonal Psychotherapy of Depression. New York, Basic Books, 1984Google Scholar

20 Elkin I, Parloff MB, Hadley SW, Autry JH: NIMH Treatment of Depression Collaborative Research Program: background and research plan. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1985; 42:305–316Crossref, Google Scholar

21 Frank E, Kupfer DJ, Wagner EF, McEachran AB, Cornes C: Efficacy of interpersonal psychotherapy as a maintenance treatment of recurrent depression: contributing factors. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1991; 48:1053–1059Crossref, Google Scholar

22 Frank E: Interpersonal psychotherapy as a maintenance treatment for patients with recurrent depression. Psychotherapy 1991; 28:259–266Crossref, Google Scholar

23 Paykel ES, Ramana R, Cooper Z, Hayhurst H, Kerr J, Barocka A: Residual symptoms after partial remission: an important outcome in depression. Psychol Med 1995; 25:1171–1180Crossref, Google Scholar

24 Frank E, Kupfer DJ, Jacob M, Jarrett D: Personality features and response to acute treatment in recurrent depression. J Personal Disord 1987; 1:14–26Crossref, Google Scholar

25 Spanier C, Frank E, McEachran AB, Grochocinski VJ, Kupfer DJ: The prophylaxis of depressive episodes in recurrent depression following discontinuation of drug therapy: integrating psychological and biological factors. Psychol Med 1996; 26:461–475Crossref, Google Scholar

26 Frank E, Perel JM, Mallinger AG, Thase ME, Kupfer DJ: Relationship of pharmacologic compliance to long-term prophylaxis in recurrent depression. Psychopharmacol Bull 1992; 28:231–235Google Scholar

27 Belsher G, Costello CG: Relapse after recovery from unipolar depression: a critical review. Psychol Bull 1988; 104:84–96Crossref, Google Scholar

28 Coryell W, Endicott J, Keller M: Outcome of patients with chronic affective disorder: a five-year follow-up. Am J Psychiatry 1990; 147:1627–1633Crossref, Google Scholar

29 Keller MB, Shapiro RW, Lavori PW, Wolfe N: Recovery in major depressive disorder: analysis with the life table. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1982; 39:905–910Crossref, Google Scholar

30 Keller MB, Shapiro RW, Lavori PW, Wolfe N: Relapse in major depressive disorder: analysis with the life table and regression models. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1982; 39:911–915Crossref, Google Scholar

31 Keller MB, Klerman GL, Lavori PW, Coryell W, Endicott J, Taylor J: Long-term outcome of episodes of major depression: clinical and public health significance. JAMA 1984; 252:788–792Crossref, Google Scholar

32 Keller MB, Lavori PW, Rice J, Coryell W, Hirschfeld RM: The persistent risk of chronicity in recurrent episodes of nonbipolar major depressive disorder: a prospective follow-up. Am J Psychiatry 1986; 143:24–28Crossref, Google Scholar

33 Fava GA: Subclinical symptoms in mood disorders: pathophysiological and therapeutic implications. Psychol Med 1999; 29:47–61Crossref, Google Scholar

34 Fava GA, Rafanelli C, Grandi S, Canestrari R, Morphy MA: Six-year outcome for cognitive behavioral treatment of residual symptoms in major depression. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:1443–1445Crossref, Google Scholar

35 Judd LL, Paulus MJ, Schettler PJ, Akiskal HS, Endicott J, Leon AC, Maser JD, Mueller T, Solomon DA, Keller MB: Does incomplete recovery from first lifetime major depressive episode herald a chronic course of illness? Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157:1501–1504Crossref, Google Scholar

36 Judd LL, Akiskal HS, Maser JD, Zeller PJ, Endicott J, Coryell W, Paulus MP, Kunovac JL, Leon AV, Mueller TI, Rice JA, Keller MB: Major depressive disorder: a prospective study of subthreshold depressive symptoms as predictor of rapid relapse. J Affect Disord 1998; 50:97–108Crossref, Google Scholar

37 Nierenberg AA, Keefe BR, Leslie VC, Alpert JE, Pava JA, Worthington JJ III, Rosenbaum JF, Fava M: Residual symptoms in depressed patients who respond acutely to fluoxetine. J Clin Psychiatry 1999; 60:221–225Crossref, Google Scholar

38 Geddes JR, Carney SM, Davies C, Furukawa TA, Kupfer DJ, Frank E, Goodwin GM: Relapse prevention with antidepressant drug treatment in depressive disorders: a systematic review. Lancet 2003; 361:653–661Crossref, Google Scholar

39 Hobson JA: The Dreaming Brain. New York, Basic Books, 1988Google Scholar

40 Pilkonis PA, Frank E: Personality pathology in recurrent depression: nature, prevalence, and relationship to treatment response. Am J Psychiatry 1988; 145:435–441Crossref, Google Scholar

41 Akiskal HS: Dysthymic disorder: psychopathology of proposed chronic depressive subtypes. Am J Psychiatry 1983; 140:11–20Crossref, Google Scholar

42 Shea MT: Personality disorders and depression: an overview of issues and findings. R I Med 1993; 76:405–408Google Scholar

43 Sadek N, Bona J: Subsyndromal symptomatic depression: a new concept. Depress Anxiety 2000; 12:30–39Crossref, Google Scholar

44 Judd LL, Paulus MP, Wells KB, Rapaport MH: Socioeconomic burden of subsyndromal depressive symptoms and major depression in a sample of the general population. Am J Psychiatry 1996; 153:1411–1417Crossref, Google Scholar