The Law and Psychiatry

Abstract

The body of law applied to the practice of psychiatry does not differ from that of medicine in general. Nevertheless, the diagnosis, treatment, and management of patients with psychiatric disorders present not only unique clinical and ethical concerns but also unique legal considerations. For instance, determination of a patient’s competency, as well as the patient’s ability to manage his or her personal affairs, may be required to determine the patient’s mental capacity to make health care decisions. Currently, competency determinations are particularly relevant for patients with Alzheimer’s disease or dementia related to AIDS. Psychiatrists commonly face ethical and legal issues such as informed consent, the right to treatment, the right to refuse treatment, substitute decision making, and advance directives when treating psychiatric patients.

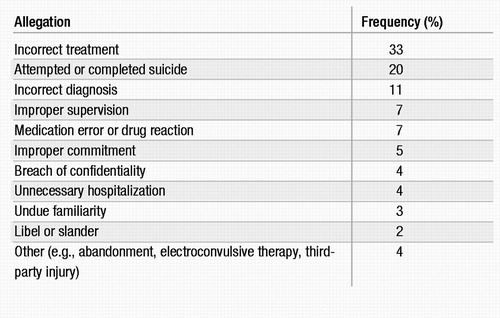

Psychiatrists’ vulnerability to malpractice suits has increased, particularly in certain areas of psychiatric practice. Table 1 summarizes the malpractice claims experience of the Professional Liability Insurance Program endorsed by the American Psychiatric Association (APA) (1). Somatic therapies, assessment and management of violent patients, techniques to recover memories of sexual abuse, sexual misconduct, boundary violations, premature discharge of potentially violent patients, and managed care settings are areas of heightened liability for the psychiatric practitioner.

The chances of a psychiatrist’s being sued in the 1980s were 1 in 25 per year (1). By 1995, however, the odds had increased to about 1 of every 12 psychiatrists per year. In some states psychiatrists were sued at the rate of 1 in 6 per year. The APA Professional Liability Insurance Program identifies several factors to account for the increase in malpractice suits:

| 1. | Psychiatrists are treating “sicker” patients in managed care settings. | ||||

| 2. | The media scrutinizes the so-called recovered memory cases and ritual satanic abuse cases. | ||||

| 3. | Tort reform legislation has failed. | ||||

| 4. | Psychiatrists are specializing in new practice areas, such as geriatric psychopharmacology, adolescent addiction medicine, dissociative disorders, pain management, and adult children of alcoholics. | ||||

| 5. | Psychiatrists are providing more primary care, such as in the management of patients with diabetes, hypertension, and a wide variety of acute general medical illnesses. | ||||

With the advent of managed care, psychiatrists treat a large volume of patients for brief visits, creating greater liability exposure. With less time spent with a patient, the likelihood of developing a working alliance is reduced. Among primary care physicians, it has been reported that those who have had no malpractice claims against tended to use more statements of orientation, laughed more and used more humor, and engaged patients more in a give-and-take dialogue than did colleagues who had been sued (2). They also spent more time in routine visits than did those who had been sued (mean, 18.3 vs. 15.0 minutes). The length of the visit was an independent factor in predicting claims status.

Despite the increase in malpractice claims, psychiatrists prevail in seven out of every eight suits brought against them. The plaintiff has the heavy burden of proving his or her malpractice claim.

Psychiatric malpractice: somatic therapies

Malpractice is the provision of substandard professional care that causes a compensable injury to a person with whom a professional relationship existed. Although this concept may seem relatively clear and simple, it has its share of conditions and caveats. For example, the essential issue is not the existence of substandard care per se, but whether there is compensable liability.

KEY POINTS:

| • | The diagnosis, treatment, and management of psychiatric disorders present clinical, ethical, and legal concerns. | ||||

| • | Malpractice suits against psychiatrists are on the increase. Practicing in managed care settings may increase psychiatrists’ exposure to malpractice liability. | ||||

| • | Psychiatrists prevail in 7 out of 8 malpractice suits. | ||||

Medical malpractice is a tort (i.e., a wrong that is noncriminal and not related to a contract). It is a type of civil wrong committed as a result of negligence by a physician that causes injury to a patient in his or her care. Negligence, the fundamental concept underlying a malpractice lawsuit, is simply described as either doing something that a physician with a duty of care (to the patient) should not have done or failing to do something that a physician with a duty of care should have done. The fact that a psychiatrist commits an act of negligence does not automatically make him or her liable to the patient who sues.

For a psychiatrist to be found liable to a patient for malpractice, four fundamental elements (see Quick Reference Table 1) must be established by a preponderance of the evidence, which essentially means “more likely than not”: 1) that there was a duty of care owed by the defendant, 2) that the duty of care was breached, 3) that the plaintiff (i.e., the patient) suffered actual damages, and 4) that the deviation was the direct cause of the damages. Each of these four elements must be met, or there can be no finding of liability, regardless of any finding of negligence. A psychiatrist may be negligent but still not found to be liable. For example, if the patient suffered no real injuries because of the negligence, or if there was an injury but it was not directly caused by the psychiatrist’s negligence, a claim of malpractice will be defeated.

Critical to establishing a claim of professional negligence is the requirement that the defendant’s conduct was substandard or was a deviation from the standard of care owed to the plaintiff. Except in the case of “specialists,” the law presumes and holds all physicians to a standard of ordinary care, which is measured by its reasonableness according to the clinical circumstances in which it is provided.

In terms of potential liability, the use of a somatic therapy, including electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), is evaluated no differently than the use of any other medical treatment or procedure. The same general standard of ordinary and reasonable care governs the assessment of whether a psychiatrist’s use of or failure to use a somatic intervention is legally actionable.

It is generally acknowledged within the psychiatric profession that there is no absolute standard protocol for the administration of psychotropic medication or ECT. Nevertheless, the existence of professional treatment guidelines and procedures that are generally accepted or used by a significant number of psychiatrists should prompt clinicians to consider such guidelines as practice reference sources. For example, APA has published comprehensive findings and guidelines in the form of task force reports on ECT (3) and tardive dyskinesia (4). Nevertheless, official guidelines must not preempt sound professional judgment in attending to the specific clinical needs of patients.

Published guidelines and procedures do not, per se, establish the standard of care by which a court might evaluate a psychiatrist’s treatment, but they do represent a credible source of information with which a reasonable psychiatrist should at least be familiar and should have considered (Stone v. Proctor 1963). In addition to expert testimony, courts generally consider official guidelines and the professional literature that establish contemporary psychiatric practices in determining the standard of care.

There is less professional autonomy and flexibility associated with the use of ECT. Usually, the “reasonable care” standard applied to psychiatric treatment is construed in a fairly broad manner. However, some psychiatric treatments are more rigidly regulated than others. For instance, the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO) considers ECT a “special treatment” procedure, to be regulated by written policies. Whenever ECT is used, the procedure must be adequately justified and documented in the patient’s medical chart (5). The ECT policies of treatment facilities as well as judicial decisions and statutory regulation of ECT can also serve as establishing the basis for liability, if violated. Malpractice suits involving ECT are infrequent.

The standard for judging the use and administration of medication, on the other hand, appears to be consistent with the more flexible and general reasonable care requirement. Another reference source is the Physicians’ Desk Reference (PDR), which may be used to establish or dispute a psychiatrist’s pharmacotherapy procedures. The PDR is a commercially distributed and privately published reference of medication products used in the United States. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) requires that drug manufacturers have their official package inserts reported in the PDR (6). Accordingly, psychiatrists consult publications such as the PDR as needed for current and accurate medication information. Although numerous courts have cited the PDR as a credible source of medication-related information in the medical profession, the PDR does not by itself establish the standard of care. Rather, it may be used as one piece of evidence to establish the standard of care in a particular situation. Courts generally hold that drug inserts alone do not set the standard of care. They are only one element to be considered, along with previous clinical experience, the scientific literature, approvals in other countries, expert testimony, and other pertinent factors. The presence of a substantial scientific literature that justifies the clinician’s treatment is vastly more persuasive than FDA approval. The PDR or any other reference cannot serve as a substitute for the psychiatrist’s sound clinical judgment.

Fortunately, courts recognize the importance of professional judgment and give psychiatrists, like other medical specialists, latitude in explaining special diagnostic or treatment considerations that guide their decision making. For instance, the clinical data regarding pharmacological treatment of rapid-cycling bipolar disorder indicate that a variety of potentially useful drug therapies exist, some of which are considered experimental or on the cutting edge (7). Various drugs and hormones, for example, are clinically useful as mood stabilizers, such as carbamazepine, clozapine, thyroid and estrogen replacement therapy, calcium channel blockers, antihypertensives, neuroleptics, atypical antipsychotics, and other anticonvulsants (lamotrigine, valproate, and gabapentin).

The courts consider that no one treatment of choice exists and that treatment applications are still being developed. Evidence that a treatment procedure is accepted by at least a respectable minority of professionals in the field can establish that a particular treatment is a reasonable professional practice (8). The final word on treatment interventions is determined by the clinician and the clinical needs of the patient, not the law.

Theories of liability

Although no reliable compilation of malpractice claims data has been published, anecdotal information suggests that medication-related lawsuits constitute a significant share of the litigation filed against psychiatrists. As noted, claims data from the APA Professional Liability Insurance Program showed that medication error and drug reactions constituted 7% of malpractice allegations.

Evaluation

Sound clinical practice requires that before any form of treatment is initiated, the patient should be properly evaluated. The nature and extent of an evaluation is largely dictated by the type of treatment being contemplated and the patient’s medical and psychiatric condition. A physical examination should be conducted or obtained if clinically indicated. A recently performed physical examination may suffice, or patients may be referred elsewhere if the psychiatrist does not perform physical examinations. Lawsuits have resulted from failure to evaluate a patient properly before administering medications.

Monitoring

Probably the most common act of negligence associated with pharmacotherapy is the failure to monitor the patient while he or she is taking medication, including carefully following the patient for adverse side effects.

Once psychotropic medication is prescribed, it is the psychiatrist’s duty to monitor the patient. Consultation or referral may be necessary according to the clinical needs of the patient. Monitoring may require the use of laboratory testing. Serum drug levels are obtainable for a number of psychotropic medications. The primary indications for laboratory tests include assessment of therapeutic and toxic levels of medication and of the patient’s adherence to the medication regimen. The use of carbamazepine, valproate, and clozapine requires periodic monitoring of the hematopoietic system and the liver. Failure to supervise patients to ensure that they are taking medications properly can delay or prevent the detection of harmful side effects and a change to more effective treatment. If a patient is harmed, a malpractice action may result.

KEY POINTS:

| • | Mistakes alone are not malpractice when the appropriate standard of care is provided. | ||||

| • | Psychiatrists are held to a standard of ordinary, not excellent care. | ||||

| • | Professional treatment guidelines should be used as a practice resource. | ||||

| • | The PDR or drug insert does not set the standard of care. It is only one factor among many to be considered. | ||||

| • | The courts recognize the importance of professional judgment in diagnostic and treatment decisions. | ||||

| • | Medication errors are a common cause of lawsuits against psychiatrists. | ||||

Split treatment

Split treatment situations require that the psychiatrist keep informed about the patient’s clinical status as well as about the nature and quality of treatment the patient is receiving from the nonmedical therapist (9). In a collaborative relationship, responsibility for the patient’s care is shared according to the qualifications and limitations of each discipline. The responsibilities of each discipline do not diminish those of the other disciplines. Patients should be informed of the separate responsibilities of each discipline. Periodic evaluation by the psychiatrist and the nonmedical therapist of the patient’s clinical condition and needs is necessary to determine whether the collaboration should continue. On termination of the collaborative relationship, the patient should be informed in a clinically supportive manner. In split treatments, if negligence is claimed on the part of the nonmedical therapist, it is likely that the collaborating psychiatrist will be sued, and vice versa (10).

In managed care or similar treatment settings, the mere prescribing of medication without an informed working relationship between patient and physician does not meet generally accepted standards of good clinical care. Fragmented care, in which the psychiatrist functions only as a prescriber of medication while remaining uninformed about the patient’s overall clinical status, constitutes substandard treatment that may lead to a malpractice action. Such a practice may diminish the efficacy of the drug treatment itself or even lead to the patient’s failure to take the prescribed medication.

Psychiatrists who prescribe medication in split treatment arrangements should be able to hospitalize a patient if necessary. If the psychiatrist does not have admitting privileges, prearrangements should exist with other psychiatrists who can hospitalize a patient if an emergency arises.

KEY POINTS:

| • | Failure to monitor is the most common act of negligence associated with pharmacotherapy. | ||||

| • | In split treatment situations, continuing collaboration is essential. | ||||

| • | The psychiatrist, not a restrictive formulary, should determine which medications are appropriate for the patient. | ||||

| • | Prescription practices will be evaluated by the reasonableness and ordinary practice standard. | ||||

| • | Substitute decision makers are required for patients who lack health care decision-making capacity. | ||||

| • | Patients receiving antipsychotic medications require monitoring according to their clinical needs. No standard frequency has been defined. | ||||

| • | The APA Task Force on Electroconvulsive Therapy recommends procedures for ECT. | ||||

| • | Official practice guidelines cannot substitute for clinicians’ sound clinical judgment with individual patients. | ||||

Prescription practices

The selection of a medication, determination of initial dosage and form of administration, and related procedures are all decisions left to the professional discretion of the treating psychiatrist. In managed care settings, psychiatrists should vigorously resist attempts to limit their choice of drugs by a restrictive or closed formulary or by therapeutic substitution (interchanging different chemical agents from the same therapeutic class, such as a tricyclic antidepressant substituted for a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor). The prescribing of specific medications should be determined by the psychiatrist and the clinical needs of the patient. An appeal should be filed if a drug that is not formulary approved is denied. The law recognizes that the physician is in the best position to “know the patient” and to determine what course of treatment is best under the circumstances. The standard by which a psychiatrist’s prescription practices will be evaluated is that of reasonableness. In administering psychotropic medication, psychiatrists need only conform their procedures and decision making to those that are ordinarily practiced by other psychiatrists under similar circumstances.

A review of cases involving allegations of negligent prescription procedures reveals several common practices that represent potential deviations from generally accepted treatment practice:

| ■ | Exceeding recommended dosages without clinical indications | ||||

| ■ | Negligently prescribing multiple drugs | ||||

| ■ | Negligently prescribing medication for uses not approved by the FDA | ||||

| ■ | Negligently prescribing unapproved medications | ||||

| ■ | Negligently failing to disclose medication risks | ||||

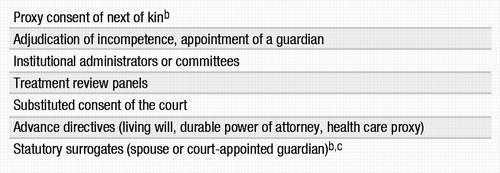

A physician who prescribes medication has a duty to first obtain the informed consent of the patient (see Quick Reference Table 5). Obtaining competent informed consent may be complicated by the fact that some psychiatric patients exhibit compromised mental capacity for health care decision making as a result of their mental illness. Patients lacking such decision-making capacity require consent for treatment by substitute decision makers (Table 2).

Whenever a medication is changed and a new drug is prescribed, informed consent should be obtained. Failure to inform a patient properly of the risks and benefits of a prescribed medication can be grounds for a malpractice action, if the patient is injured as a result.

Other areas of negligence involving medication that have resulted in legal action include 1) failure to treat side effects after they have been recognized or should have been recognized, 2) failure to monitor a patient’s compliance with prescription limits, 3) failure to prescribe medication or appropriate levels of medication according to the patient’s treatment needs, 4) failure to refer a patient for consultation or treatment by a specialist, and 5) negligent withdrawal from medication and unclear or illegible medication orders or prescriptions.

Tardive dyskinesia

The development of neuroleptic medications in the mid-1950s dramatically improved the treatment and management of patients with schizophrenia. However, shortly after the introduction of neuroleptic medications as therapeutic agents, researchers and clinicians observed unusual muscle movements in some patients, referred to as tardive dyskinesia.

The risk of developing tardive dyskinesia is estimated at 4%–7% per year of neuroleptic use. These projections are even higher for elderly patients. With the use of atypical antipsychotic drugs, the risk of developing tardive dyskinesia is expected to be lower. Despite the possibility of a large number of lawsuits related to tardive dyskinesia, relatively few psychiatrists have been sued.

Allegations of negligence after a patient develops tardive dyskinesia are based on the same legal elements as any other malpractice action. The bases for negligence mirror those previously identified in general medication cases. These areas include but are not limited to:

| • | Failure to evaluate and monitor a patient properly | ||||

| • | Failure to obtain informed consent | ||||

| • | Negligent diagnosis of a patient’s condition | ||||

| • | Wrongful prescription of neuroleptic medication | ||||

| • | Failure to monitor medication side effects | ||||

Patients receiving antipsychotic medications must be monitored with frequent evaluations. No stock answer can be given to the question of how frequently the psychiatrist should see a patient. Generally, psychiatrists should schedule return visits with a frequency that is in accord with the patient’s clinical need. However, the longer the time between visits, the greater the risk that the psychiatrist will miss adverse drug reactions and untoward developments in the patient’s condition. The interval between visits ordinarily should not exceed 6 months.

The defenses and preventive measures applicable to malpractice claims related to tardive dyskinesia are consistent with those used in any case alleging negligent drug treatment. Sound clinical practice accompanied by the patient’s competent informed consent, appropriately documented in the medical chart, serves as an effective foil to any allegations of negligence should tardive dyskinesia develop.

Electroconvulsive therapy

With the shortening of hospital lengths of stay in recent years, the use of ECT appears to be increasing. Legal actions alleging negligence associated with ECT are infrequent. Cases involving ECT-related injuries have included a variety of circumstances in which negligence has occurred. These cases can be categorized into three groups: pretreatment, treatment, and posttreatment.

Pretreatment. Although pre-ECT evaluations vary somewhat, generally the following procedures, recommended by the APA Task Force on Electroconvulsive Therapy (3), should be performed:

1. A psychiatric history and examination to evaluate the indications for ECT

2. A medical examination to determine risk factors

3. Anesthesia evaluation

4. Informed consent (written)

5. An evaluation by a physician privileged to administer ECT

Although these recommendations do not define in absolute terms the standard of care for ECT, they may be proffered as evidence of the standard of care in malpractice suits involving ECT. Official treatment guidelines, however, should not be a substitute for the psychiatrist’s sound clinical judgment. Nevertheless, failure to conduct appropriate pretreatment procedures could endanger the welfare of the patient and ultimately result in a lawsuit.

Treatment. Lawsuits involving ECT-related injuries in which the negligence is related to the actual treatment process include the following errors:

| ■ | Failure to use a muscle relaxant to reduce the chance of a bone fracture | ||||

| ■ | Negligent administration of the procedure | ||||

| ■ | Failure to conduct an evaluation of the patient before continuing treatment | ||||

Posttreatment. It is common for patients treated with ECT to experience side effects such as temporary confusion, disorientation, and memory loss immediately after treatment. Because of these temporary debilitating effects, sound clinical practice requires that psychiatrists provide reasonable posttreatment care and safeguards. Courts have held that the failure to attend properly to a patient for a period of time after administering ECT can result in malpractice liability. The following are examples of posttreatment circumstances that may constitute a basis for a lawsuit:

| ■ | Failure to evaluate complaints of pain or discomfort after treatment | ||||

| ■ | Failure to evaluate a patient’s condition before resuming ECT treatments | ||||

| ■ | Failure to monitor a patient properly to prevent falls | ||||

| ■ | Failure to supervise properly a patient who was injured as a result of ECT | ||||

As a source of civil liability, ECT-related lawsuits today are infrequent and are not likely to represent a significant malpractice risk for psychiatrists.

Right to refuse treatment

Buttressed by constitutionally derived rights to privacy and freedom from cruel and unusual punishment, the common law tort of battery, and the doctrine of informed consent, mentally disabled persons are increasingly being afforded protections traditionally reserved for the legally competent. This new freedom often runs counter to the dictates of clinical judgment (i.e., to treat and protect). As a result of this conflict, the courts vary considerably on the parameters of this right and the procedures to be followed.

KEY POINTS:

| • | In litigating right to refuse treatment cases, the courts have split between treatment-driven and rights-driven models. | ||||

| • | Clinicians cannot foresee who will commit suicide. However, a patient’s nearterm risk of suicide is foreseeable after proper assessment. | ||||

| • | Foreseeability should not be confused with preventability. In hindsight, suicides may seem preventable but were not foreseeable at the time of assessment. | ||||

| • | Systematic suicide risk assessment is essential to the treatment and management of the suicidal patient. | ||||

| • | Psychiatrists are more frequently sued for inpatient than outpatient suicides. | ||||

| • | Suicide prevention contracts must not take the place of systematicsuicide risk assessment. | ||||

Two landmark cases illustrate this point. In Rennie v. Klein (1978), the Third Circuit Court of Appeals recognized a right to refuse treatment in the state of New Jersey. The court, after extended litigation, found that this right could be overridden and antipsychotic drugs administered “whenever, in the exercise of professional judgment, such an action is deemed necessary to prevent the patient from endangering himself or others.” In a Massachusetts case, Rogers v. Commissioner of Department of Mental Health (1983), the court decided that in the absence of an emergency (e.g., serious threat of extreme violence or personal injury), any person who has not been adjudicated incompetent has a right to refuse antipsychotic medication. Incompetent persons have a similar right, but it must be exercised through a “substituted judgment treatment plan” that has been reviewed and approved by the court.

These two decisions are often viewed as legal bookends to the issue of the right to refuse treatment. The cases suggest parameters for other courts attempting to define such a right. The Rennie case became the model for subsequent legal decisions that adopted a treatment-driven rationale for the right to refuse treatment. Rogers became the basis for rights-driven approaches taken by some courts in litigating the right to refuse treatment.

Numerous state and federal decisions have tackled some aspect of this issue. Generally speaking, there is near-judicial recognition of an involuntarily hospitalized patient’s right to refuse medication absent an emergency. Case law criteria for emergencies range from a risk of imminent harm to self or others to a deterioration in the patient’s mental condition if treatment is halted. Until either more states enact legislation or the U.S. Supreme Court rules squarely on this issue, jurisdictions will continue to vary on the substance of the right to refuse treatment and the procedures by which such a right can be implemented.

The suicidal patient

The most common legal action involving psychiatric care is the failure to provide reasonable protection to patients from harming themselves. Theories of negligence involving suicide can be grouped into three broad categories: failure to diagnose properly, that is, to assess the potential for suicide; failure to treat, that is, to use reasonable treatment interventions and precautions; and failure to implement, that is, to carry out treatment properly and not negligently.

These theories, each of which applies to inpatient and outpatient settings, are based on the practitioner’s failure to act reasonably in exercising the appropriate duty of care owed to the patient. Wrongful death suits as a result of patient suicides are based on the legal concepts of foreseeability, reasonableness, and causation. A typical lawsuit argues that a patient with the potential for suicide was not diagnosed and treated properly, resulting in the patient’s death.

As a general rule, a psychiatrist who exercises reasonable care in compliance with accepted medical practice will not be held liable for any resulting injury. Normally, if a patient’s suicide was not reasonably foreseeable, or if the suicide occurred as a result of intervening factors, this rule will apply.

Foreseeable suicide

The evaluation of suicide risk is one of the most complex, difficult, and challenging clinical tasks in psychiatry. A comprehensive assessment of a patient’s suicide risk is critical to a sound clinical management plan. Using reasonable care in assessing suicide risk can preempt the problem of predicting the actual occurrence of suicide, for which professional standards have not yet been developed. The risk of suicide is foreseeable, but not the prediction of who will commit suicide. Standard approaches to the assessment of suicide risk are described in the psychiatric literature (11–14). Short-term suicide risk assessments are more reliable than long-term assessments. Time attenuates suicide risk assessments, requiring that assessment be a process, not an event.

As an accepted standard of care, an evaluation of suicide risk should be done with all patients, regardless of whether they present with overt suicidal complaints. A review of case law shows that reasonable care requires that a patient who is either suspected of being or confirmed to be suicidal must be the subject of certain affirmative precautions. A failure either to assess reasonably a patient’s suicide risk or to implement an appropriate precautionary plan after the suicide risk becomes foreseeable is likely to render a practitioner liable if the patient is harmed because of a suicide attempt. The law tends to assume that suicide is preventable if it is foreseeable. Foreseeability, however, should not be confused with preventability. In hindsight, many suicides seem preventable that were clearly not foreseeable.

When suicide risk assessments are competently performed and recorded, the psychiatrist demonstrates that he or she was careful and thorough in the management of the suicidal patient. Moreover, evidence of a reasonable suicide risk assessment also demonstrates that the psychiatrist adhered to the prevailing standard of care. Although psychiatrists cannot ensure favorable outcomes with suicidal patients, they can ensure that the process of suicide risk assessment was competently performed (15).

Inpatients

Intervention in an inpatient setting usually requires the following:

| ■ | Screening evaluations | ||||

| ■ | Development of an individualized treatment plan | ||||

| ■ | Implementation of that plan | ||||

| ■ | Ongoing case review by clinical staff | ||||

Careful documentation of assessments and of management interventions that remain responsive to the patient’s clinical situation should be considered evidence of clinically and legally sufficient psychiatric care. Systematic suicide risk assessment is essential. Documenting the benefits of a psychiatric intervention (e.g., ward change, pass, and discharge) against the risk of suicide permits an evenhanded approach to the clinical management of the patient. Systematic suicide risk assessment evaluates both risk and protective factors. Consideration only of a patient’s suicide risk is a manifestation of defensive psychiatry that usually interferes with good clinical care, further exposing the psychiatrist to malpractice liability.

Psychiatrists are more likely to be sued when a psychiatric inpatient commits suicide. The law presumes that the opportunities to foresee (i.e., anticipate) and control (i.e., treat and manage) suicidal patients are greater in the hospital setting.

Outpatients

Psychiatrists are expected to reasonably assess the patient’s risk of suicide. The result of the assessment dictates the duty-of-care options. Courts have reasoned that when an outpatient commits suicide, the therapist has not necessarily breached a duty to safeguard the patient from foreseeable self-harm because of the difficulty in controlling the patient. Instead, the reasonableness of the psychiatrist’s assessment, treatment, and management is determinative.

Suicide prevention pacts

Suicide prevention contracts created between the clinician and the patient attempt to develop an expressed understanding that the patient will call for help rather than act out suicidal thoughts or impulses. These contracts have no legal authority. Although they may be helpful in solidifying the therapeutic alliance, they may falsely reassure the psychiatrist. Suicide prevention agreements between psychiatrists and patients must not be used in place of adequate suicide assessment (16). There is no evidence that suicide prevention contracts decrease the risk of suicide.

KEY POINTS:

| • | In suicide cases, the bestjudgment defense is available when the patient was properly assessed and treated. | ||||

| • | Psychiatrists are unable to predict violent behaviors with accuracy. | ||||

Legal defenses

One legal defense that has created a split in the courts involves the use of the “open-door” policy, in which patients are allowed freedom of movement for therapeutic purposes. The individual facts of the case and reasonableness of the staff’s application of the open-door policy appear to be paramount. Nevertheless, courts have difficulty with abstract treatment notions such as personal growth when faced with a dead patient.

Another defense, the doctrine of sovereign or governmental immunity, may by statute bar a finding of liability against a state or federal facility. An intervening cause of suicide over which the clinician had no control is another valid legal defense. For example, a court may find a psychiatrist not liable for the suicidal act of a patient with borderline personality disorder who experienced a significant rejection between therapy sessions and then impulsively attempted suicide, without trying to contact the psychiatrist. The court may rule that the suicide was caused by the superseding intervening variable of an unforeseen rejection and not by the psychiatrist’s negligence. Finally, the best-judgment defense has been used successfully when the patient was properly assessed and treated for suicide risk but he or she committed suicide anyway (17).

The violent patient

As a general rule, one person has no duty to control the conduct of a second person to prevent that person from physically harming a third person. Applying this rule to psychiatric care, psychiatrists traditionally have had only a limited duty to control hospitalized patients and to exercise due care on discharge. After the Tarasoff ruling, the therapist’s legal duty and potential liability significantly expanded. In Tarasoff, the California Supreme Court first recognized that a duty to protect third parties was imposed only when a special relationship existed between the victim, the individual whose conduct created the danger, and the defendant. The court stated that “the single relationship of a doctor to his patient is sufficient to support the duty to exercise reasonable care to protect others” from the violent acts of patients.

KEY POINTS:

| • | In the MacArthur Violence Risk Assessment Study, violence risk assessments were found to have a validity modestly greater than chance. | ||||

| • | In most cases, the duty to warn and protect arises when the threat of violence is imminent and serious toward an identified third party. | ||||

| • | The duty to warn and protect should be considered a national standard. | ||||

| • | Psychiatric units have become shortstay acute-care facilities. | ||||

| • | Lawsuits alleging negligent release of foreseeably dangerous patients are five to six times more common than outpatient dutyto-warn litigation. | ||||

| • | No standard of care exists for the prediction of violence. | ||||

| • | Professional standards do exist for the assessment of risk factors for violence. | ||||

Psychiatrists do not have the ability to predict violence with any accuracy. Violent behaviors are the result of the complex interplay among social, clinical, and personality factors that vary significantly across situations and time (18). Nonetheless, clinical methods for assessing the risk of violence are available that reflect the current standard of care (6, 19–21).

The MacArthur Violence Risk Assessment Study (22) was established to improve clinical risk assessment validity, to enhance effective clinical risk management, and to provide data on mental disorders and violence for informing mental health law and policy. The study found that the validity of violence risk assessments is modestly better than chance. Until more studies are available, sound clinical practice requires that thorough violence risk assessments be routinely performed on potentially violent patients on the basis of current knowledge of violence risk factors. In inpatient settings, violence risk assessments need to be made at such critical points as the initiation of ward status changes, passes, and discharge. Violence risk assessment is more of a continuing process than a solitary event. All such assessments should be duly recorded.

The index of suspicion for potential violence should be high for patients with a past history of violence who are making current, serious threats of harm toward specific individuals. The potential for violence is further heightened if the patient is acutely psychotic, substance abusing, angry, fearful of being harmed, and experiencing delusions of being controlled or influenced (23).

After the Tarasoff ruling, courts in other jurisdictions have interpreted the case variously. Some states have adopted the Tarasoff holding, whereas others have limited or extended its scope and reach. In most states, psychotherapists have a duty, established by case law or statute, to act affirmatively to protect an endangered third party from a patient’s violent or dangerous acts. A few courts have declined to find a Tarasoff duty in a specific case, whereas some courts have simply rejected the Tarasoff duty. The Texas Supreme Court ruled that the state statute permits but does not require disclosures by therapists of threats of harm to third parties by their patients.

Most courts have found no duty to protect without an imminent threat of serious harm to a foreseeable victim. Only a small minority of courts have held that a duty to protect exists for the population at large. In some jurisdictions, courts have held that the need to safeguard the public well-being overrides all other considerations, including confidentiality. Although a few courts have declined to find a Tarasoff duty in a specific case, a growing number of courts have recognized some variation of the original Tarasoff duty. Despite the fact that the Tarasoff duty is still not law in some jurisdictions and is subject to different interpretations by individual courts, clinicians should consider the duty to protect to be a national standard of practice.

Several states have enacted immunity statutes that protect the psychiatrist from legal liability caused by a patient’s violent acts toward others (24). Most of these statutes define the therapist’s duty in terms of warning the endangered third party or notifying the authorities. The duty-to-protect language used in some statutes allows for a greater variety of clinical interventions.

Evolving trends

An important evolving trend is the application of the Tarasoff duty to sexual abuse cases by an alleged pedophile. A psychiatrist who knew that one of his patients, a psychiatric resident, was a pedophile was successfully sued for not reporting that fact to the medical school at which the resident was training. The resident molested a child at a hospital crisis center. The court reasoned that the defendant’s control over the psychiatric resident was far greater than in the typical psychiatrist-patient relationship. A Tarasoff duty was also found where a spouse had knowledge of her husband’s sexually abusive behavior against children in the neighborhood. In another case, the court found that a Tarasoff duty could exist but declined to find the parents of a babysitter liable for his dangerous sexual behavior. The court determined that no evidence existed that the parents knew of their son’s proclivity to commit a sexual assault.

Release of potentially violent patients

Under managed care, discharging violent or potentially violent inpatients presents unique challenges for treating psychiatrists (25). The treatment of psychiatric inpatients has changed dramatically in the managed care era (26). Most psychiatric units, particularly in general hospitals, have become short-stay acute-care psychiatric facilities. Generally, only suicidal, homicidal, or gravely disabled patients with major psychiatric disorders pass strict precertification review for hospitalization (27). Close scrutiny by utilization reviewers permits only brief hospitalization for such patients (28). The purpose of hospitalization is crisis intervention and management to stabilize patients and to ensure their safety. Although treatment for these patients is provided by a variety of mental health professionals, the psychiatrist usually must bear the ultimate burden of liability for treatments gone awry (29). Usually the prospects are limited for psychiatrists to develop a therapeutic alliance with patients during the hospital stay. Opportunities to communicate with patients, the psychiatrist’s stock-in-trade, are often severely curtailed. All these factors contribute to a greatly increased risk of malpractice suits against psychiatrists alleging premature or negligent discharge of patients due to cost-containment policies.

More control can be maintained over the patient in the hospital setting than in outpatient treatment. Courts closely evaluate decisions made by psychiatrists treating inpatients that adversely affect the patient or a third party. Liability imposed on psychiatric facilities that had custody of patients who injured others outside the institution after escape or release is clearly distinguishable from the factual situation of Tarasoff. Duty-to-warn cases generally involve patients in outpatient treatment. Liability arises from the inaction of the therapist, who fails to take affirmative measures to warn or protect endangered third parties. In negligent-release cases, liability may arise from the allegation that the institution’s affirmative act in releasing the patient caused injury to the third party. Nonetheless, allegations may be made that a psychiatrist or hospital personnel failed, prior to the patient’s discharge, to warn individuals known to be at risk of harm from that patient. Lawsuits stemming from the release of foreseeably dangerous patients who subsequently injure or kill others are roughly five to six times more common than outpatient duty-to-warn litigation (30).

The psychiatrist’s liability is determined by reference to professional standards. Consultation with other psychiatrists may provide additional protection when the discharge of a potentially violent patient appears problematic. Consulting with an attorney may help clarify legal obligations. However, lawyers tend to be highly risk averse and conservative when making recommendations. Sound legal advice may not necessarily accord with the clinical realities of the management of a specific patient. Clinicians must continue to exercise their professional judgment.

The patient’s willingness to cooperate with the psychiatrist is critical to maintaining follow-up treatment. The psychiatrist’s obligation focuses on structuring the follow-up visits in such a manner as to encourage compliance. A study of Veterans Administration (VA) inpatient referrals to a VA mental health outpatient clinic showed that of 24% of inpatients referred, approximately one-half failed to keep their first appointments (31). Nevertheless, there are limitations on the extent of the psychiatrist’s ability to ensure follow-up care. Most patients retain the right to refuse treatment. These limitations must be acknowledged by both the psychiatric and legal communities (6). The American Medical Association Council on Scientific Affairs has developed evidence-based discharge criteria for safe discharge from the hospital (32).

In either the outpatient or inpatient situation, psychiatrists are in compliance with the responsibility to warn and protect others from potentially violent patients if they reasonably assess a patient’s risk for violence and make clinically appropriate interventions on the basis of their findings. Although professional standards exist for assessment of the risk factors for violence (33), no standard of care has been established for the prediction of violent behavior. The clinician should assess the risk of violence frequently, updating the risk assessment at significant clinical junctures (e.g., room and ward changes, passes, and discharge). A risk-benefit assessment should be conducted and recorded before a pass or discharge is issued. Assessing the risk of violence is a “here and now” determination performed at the time of discharge. After the patient is discharged, the potential for violence against self or others depends on the nature and course of the mental illness, adequacy of treatment after discharge, adherence to treatment recommendations, and exposure to unforeseeable stressful life events.

KEY POINTS:

| • | The core substantive criteria for involuntary hospitalization are mental illness and dangerousness to self or others. | ||||

| • | Clinicians only certify patients for involuntary hospitalization. Courts determine commitment. | ||||

| • | Commitment statutes are permissive; they do not require that patients be involuntarily hospitalized. | ||||

Involuntary hospitalization

A person may be involuntarily hospitalized only if certain statutorily mandated criteria are met. Three main substantive criteria serve as the foundation for all statutory commitment requirements: the individual must 1) be mentally ill, 2) be dangerous to self or others, and/or 3) be unable to provide for his or her basic needs. Generally, each state spells out which criteria are required and what each means. Terms such as “mentally ill” are often loosely described, thus leaving the responsibility for proper definition to the clinical judgment of the petitioner.

In addition to individuals with mental illness, certain states have enacted legislation that permits involuntary hospitalization of three other distinct groups: persons with developmental disabilities (mental retardation), persons with substance (alcohol or drugs) addiction, and minors with mental disabilities. Special commitment provisions as well as various due process rights may govern requirements for the admission and discharge of mentally disabled minors.

Involuntary hospitalization of psychiatric patients usually occurs when violent behavior threatens to erupt toward the self or others and when patients become unable to care for themselves. Such patients frequently manifest mental disorders and conditions that readily meet the substantive criteria for involuntary hospitalization.

Clinicians do not commit patients. Commitment is solely under the jurisdiction of the court. The psychiatrist merely initiates a medical certification that brings the patient before the court, usually after a brief period of hospitalization for evaluation. In seeking medical certification, the psychiatrist must be guided by the treatment needs of the patient. Clinicians should not attempt to second-guess the court’s ultimate decision about involuntary hospitalization.

Commitment statutes do not require involuntary hospitalization but are permissive (24). The statutes enable mental health professionals and others to seek involuntary hospitalization for persons who meet certain substantive criteria. On the other hand, the duty to seek involuntary hospitalization is a standard-of-care issue. Patients who are mentally ill and pose an imminent, serious threat to themselves or others may require involuntary hospitalization as a primary psychiatric intervention.

KEY POINTS:

| • | In many states, psychiatrists are granted immunity from liability when reasonable professional judgment and good faith are used in petitioning for involuntary hospitalization. | ||||

| • | Involuntary hospitalization does not negate a presumption that the patient is competent. | ||||

Liability

The most common cause of a malpractice action involving involuntary hospitalization is the failure of a psychiatrist to adhere in good faith to statutory requirements, leading to a wrongful commitment. Often these lawsuits are brought under the theory of false imprisonment. Other areas of liability that may arise from wrongful commitment include assault and battery, malicious prosecution, abuse of authority, and intentional infliction of emotional distress (6).

In many states, psychiatrists are granted immunity from liability as long as they use reasonable professional judgment and act in good faith when petitioning for commitment (34). Performing a careful examination of the patient, abiding by the requirements of the law, and ensuring that sound reasoning motivates the certification of the patient are good clinical practice and, secondarily, good risk management. Evidences of willful, blatant, or gross failure to adhere to statutorily defined commitment procedures may expose a psychiatrist to a lawsuit.

Rights of involuntarily hospitalized patients

Most states recognize the right of inpatients to refuse treatment. Even though a patient may be involuntarily hospitalized, that hospitalization does not negate a presumption of competence. In most states, involuntarily hospitalized patients who refuse medication require a separate court hearing for an adjudication of incompetence and the provision of substituted consent by the court. Recently, persons hospitalized under criminal commitment have been accorded the right to refuse treatment. The courts have found that incarcerated patients’ constitutional right to due process is adequately protected by the exercise of professional judgment within the medical peer review process of the institution.

Hospitalized patients possess other rights. Patients possess rights of visitation, for example, although these rights can be temporarily suspended for proper cause related to a patient’s care and treatment. Free communications of hospitalized patients through mail, telephone, and visitors are considered a right, unless protection of the patient or others requires supervision of communications. The right to privacy includes allowing patients to have secure locker space, private toilet and shower facilities, and a minimum square footage of floor space. Protection of confidentiality is also included. Economic rights include the right to have and spend money and to handle one’s own financial affairs responsibly. In most jurisdictions, involuntarily hospitalized patients do not lose their civil rights, such as the right to manage their own money. Hospitalized patients must be paid for their work in certain jurisdictions unless it is truly therapeutic labor (i.e., work not connected with maintenance of the hospital). “Patients’ rights” are not absolute and often must be tempered by the clinical judgment of the mental health professional. Inevitably, disputes over perceived or real violations of patients’ rights arise. In some jurisdictions, statutes require that a civil rights officer or ombudsman mediate such disputes.

Recovered memory cases

Patients who allege recovered memories of abuse have sued parents and other alleged perpetrators. In a turnabout, the alleged victimizers have sued therapists whom they claim negligently induced false memories of sexual abuse. In some cases, patients have recanted and joined forces with others (usually their parents) to sue their therapists.

KEY POINTS:

| • | The guiding principle of risk management in recovered memory cases is to maintain therapist neutrality and good treatment boundaries. | ||||

The debate on recovered memory has polarized many therapists into believers and disbelievers. Most therapists hold personal beliefs about the validity of recovered memories of sexual abuse that are somewhere between the extremes. Strongly held personal biases about recovered memories represent an occupational hazard for clinicians that can undermine the therapist’s duty of neutrality to patients, creating deviant treatment boundaries and increasing the risk of incurring liability.

The basic allegation in such cases is that the therapist abandoned a position of neutrality to suggest, persuade, coerce, and implant false memories of childhood sexual abuse. The guiding principle of clinical risk management in recovered memory cases is for the therapist to maintain neutrality and establish sound treatment boundaries.

Complicating the situation is the empirical evidence about memory mechanisms. As is typical for any emerging science, contradictory findings have been reported about how and what persons in various settings retain in memory and forget. Empirical studies frequently fail to distinguish whether allegedly repressed memories are not retrieved or simply not reported to researchers.

Sound risk management rests solidly on a clinical footing and is secondarily informed by awareness of the pertinent legal issues (35). Risk management principles that should be considered when evaluating or treating a patient who recovers memories of abuse while in psychotherapy include the following:

| ■ | Maintain therapist neutrality—do not suggest abuse. | ||||

| ■ | Stay clinically focused—provide adequate evaluation and treatment for the patient’s presenting problems and symptoms. | ||||

| ■ | Carefully document the memory recovery process. | ||||

| ■ | Manage personal biases and countertransference. | ||||

| ■ | Avoid mixing treater and expert witness roles. | ||||

| ■ | Closely monitor supervisory and collaborative therapy relationships. | ||||

| ■ | Clarify nontreatment roles with family members. | ||||

| ■ | Avoid use of special techniques (e.g., hypnosis and sodium amytal) unless clearly indicated; obtain consultation before proceeding. | ||||

| ■ | Stay within professional competence—do not take cases beyond personal expertise. | ||||

| ■ | Distinguish between narrative truth and historical truth; in therapy, the therapist is largely attuned to the patient’s perception of reality. | ||||

| ■ | Obtain consultation in problematic cases. | ||||

| ■ | Foster patient autonomy and self-determination. Do not suggest lawsuits; this should be the patient’s decision after careful consideration. | ||||

| ■ | In managed care settings, inform patients with recovered memories that more than brief therapy may be required. | ||||

| ■ | When making public statements, distinguish personal opinions from scientifically established facts. | ||||

| ■ | If uncomfortable with a patient recovering memories of childhood abuse, stop and refer. | ||||

| ■ | Do not be reluctant to ask about abuse as part of a competent psychiatric evaluation. | ||||

Sexual misconduct

Therapist-patient sex is invariably preceded by progressive boundary violations in treatment (36). As a consequence, patients are frequently psychologically damaged by the precursor boundary violations as well as the eventual sexual misconduct of the therapist (37). An excellent account of the gradual erosion of treatment boundaries leading to near loss of control with a client is given by Rutter (38).

General boundary guidelines exist for conducting psychiatric treatment (39). Awareness of these guidelines and of their transgression may help alert the therapist to progressive boundary violations (40). Sexual misconduct does not occur in isolation but usually involves a variety of negligent acts of omission and commission.

KEY POINTS:

| • | Progressive treatment boundary violations precede therapist-patient sex. | ||||

| • | Many states have made therapist sexual misconduct both civilly and criminally actionable. | ||||

| • | In sexual misconduct cases, the central issue is breach of fiduciary trust by the therapist, not the patient’s consent. | ||||

| • | There is no time limitation for bringing charges of sexual misconduct in ethics and licensure proceedings. | ||||

Civil liability

Psychiatrists who sexually exploit their patients are subject to civil and criminal actions as well as ethical and professional licensure revocation proceedings. The Principles of Medical Ethics With Annotations Especially Applicable to Psychiatry (41) states that sex with a current or former patient is unethical (section 2, annotation 1). Malpractice is the most common legal liability.

In a sexual exploitation case, the plaintiff has the difficult burden of proving, by a preponderance of the evidence (i.e., “more likely than not”), that the exploitation actually took place. This burden can be met when the plaintiff provides corroborating evidence to support the claim, such as testimony from other abused (former) patients, letters, pictures, hotel or motel receipts, and identification of incriminating body markings of the exploiter. If the defendant practitioner admits to the exploitation, the plaintiff is left with the responsibility of showing that he or she sustained injuries as a result of the sexual activity. Typically, patient injury occurs in the form of emotional injury (e.g., worsened psychiatric condition, suicide attempts, and hospitalization). Expert psychiatric testimony is usually required to establish the type and extent of psychological damages as well as to establish whether a breach of the standard of care occurred.

An increasing number of states have made sexual activity with patients both civilly and criminally actionable by statute. For instance, Minnesota enacted legislation that states the following: “A cause of action against a psychotherapist for sexual exploitation exists for a patient or former patient for injury caused by sexual contact with the psychotherapist if the sexual contact occurred: 1) during the period the patient was receiving psychotherapy . . . or 2) after the period the patient received psychotherapy . . . if a) the former patient was emotionally dependent on the psychotherapist; or b) the sexual contact occurred by means of therapeutic deception.”

A few states have enacted civil statutes proscribing sexual misconduct (6). Several states make therapist sexual misconduct a crime (42). Some states prosecute sexual exploitation suits using their sexual assault statutes. Legislatures in a number of states have enacted statutes that provide civil or criminal remedies to patients who were sexually abused by their therapists (43, 44).

Three types of remedies have been codified: reporting, civil liability, and criminal prosecution. Reporting statutes require a therapist who learns of any past or current therapist-patient sex to disclose this information. A few states have civil statutes proscribing sexual misconduct (42). Civil statutes incorporate a standard of care and make malpractice suits easier to pursue. For example, Minnesota’s statute provides a specific cause of action against psychiatrists and other psychotherapists for injury caused by sexual contact with a patient. Some of these statutes also restrict unfettered discovery of the plaintiff’s past sexual history. Criminal sanctions may be the only remedy for exploitative therapists without malpractice insurance, therapists who are unlicensed, or therapists who do not belong to professional organizations.

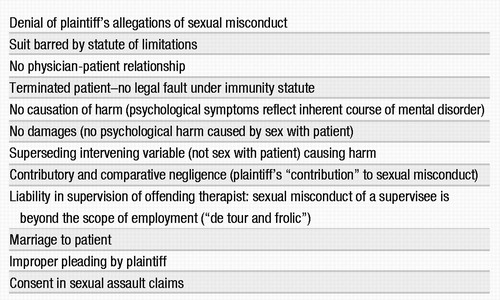

Other civil theories and defenses

Various causes of action may be asserted by a plaintiff who has been sexually exploited by a psychotherapist. In a minority of states, spouses of the injured patient also have legal standing to initiate their own cause of action against an exploitative practitioner on the grounds of loss of consortium (i.e., interference with the marital relationship).

A variety of defenses have been raised to diminish or protect against liability, but to date, few have been legally successful (Table 5). For instance, the contention that the patient was aware that sex was not a part of treatment, that the sex occurred outside the treatment setting, that treatment ended before the sexual relationship began, or that the patient consented to the sexual contact have all been rejected by the courts. Patients cannot consent to malpractice. In sexual misconduct cases, the issue is never the patient’s consent but always breach of fiduciary trust by the therapist.

There is no “respected minority” in the profession that claims that sexual relations with patients is therapeutic. This position had a few adherents at one time but is no longer publicly advocated by credible mental health professionals.

Criminal sanctions

Sexual exploitation of a patient, under certain circumstances, may be considered rape or some analogous sexual offense and may therefore be criminally actionable (45). Typically, the criminality of the exploitation is determined by one of three factors: the practitioner’s means of inducement, the age of the victim, or the availability of a relevant state criminal code.

Sex with a current patient may be criminally actionable under sexual assault statutes if the state can prove beyond a reasonable doubt (i.e., with 90%–95% certainty) that the patient was coerced into engaging in the sexual act. Typically, this type of evidence is limited to the use of some form of substance (e.g., medication) either to induce compliance or to reduce resistance. Anesthesia, ECT, hypnosis, drugs, force, and threat of harm have been used to coerce patients into sexual submission (46). To date, claims of psychological coercion through the manipulation of transference phenomena have not been successful in establishing the coercion necessary for a criminal case. In cases involving a minor patient, the issue of consent or coercion is irrelevant because minors and adult incompetent persons are considered unable to provide valid consent. Therefore, sex with a child or an incompetent person is automatically considered a criminal act.

Professional disciplinary action

For the purposes of adjudicating allegations of professional misconduct, licensing boards are typically granted certain regulatory and disciplinary authority by state statutes. As a result, state licensing organizations, unlike professional associations, may discipline an offending professional more effectively and punitively by suspending or revoking his or her license. Because licensing boards are not as restrained by rigorous rules of evidence in trial procedures as the courts are in civil and criminal actions, it is generally easier for the patient to seek redress through this means. Moreover, no time limitations exist for bringing charges. A review of published reports of sexual misconduct cases adjudicated before licensing boards revealed that in a vast majority of cases, the evidence was reasonably sufficient to substantiate a claim of exploitation, leading to revocation of the professional’s license or suspension from practice for varying lengths of time, including permanent suspension.

Patients can bring ethical charges against psychiatrists before the district branches of APA. Ethical violators may be reprimanded, suspended, or expelled from APA. All national organizations of mental health professionals have ethically proscribed sexual relations between therapist and patient. Ethical charges can be filed only against members of a professional group; therefore, this option is not available to patients whose therapists do not belong to a professional organization.

Confidentiality and testimonial privilege

Confidentiality refers to the right of a patient to have communications spoken or written in confidence undisclosed to outside parties without implied or expressed authorization. Privilege, or more accurately testimonial privilege, can be viewed as a derivation of the right of confidentiality. Testimonial privilege is a statutorily created rule of evidence that permits the holder of the privilege (e.g., the patient) to exercise the right to prevent the person to whom confidential information was given (e.g., the psychiatrist) from disclosing it in a judicial proceeding.

Confidentiality

Clinical-legal foundation. The basis for recognizing and safeguarding patient confidences is derived from four general sources. First, states have acknowledged this right of protection by including confidentiality provisions in either professional licensure laws or confidentiality and privilege statutes. The second source, and probably the most traditional, comprises the ethical codes of the various mental health professions. Third, the common law recognizes an attorney-client privilege, but developing case law has also carved out this source of protection for physicians and psychotherapists. In 1996, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that communications between psychotherapist and patient are confidential and need not be disclosed in federal trials. Fourth, the right of confidentiality may be subsumed under the right of privacy.

Breaching confidentiality. Regardless of the basis of the right of confidentiality, once the physician-patient relationship has been created, the professional assumes an automatic duty to safeguard a patient’s disclosures. This duty is not absolute, and there are circumstances in which breaching confidentiality is both ethical and legal.

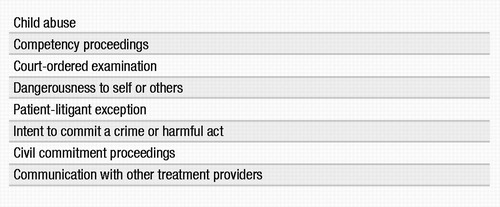

Patients waive confidentiality in a variety of situations, especially in managed care settings. Medical records are regularly sent to potential employers or to insurance companies when benefits are requested. A limited waiver of confidentiality ordinarily exists when a patient participates in group therapy. Whether one group member can be compelled in court to disclose information shared by another group member during group therapy has not been settled legally (47). Many state confidentiality statutes provide exceptions to confidentiality between the psychiatrist and the patient in one or more situations (48) (Table 6).

Patients’ access to their own records is normally controlled by statutes. These statutory provisions are found under the heading of “medical records” or the much broader term “privilege.”

If a patient gives the psychiatrist good reason to believe that a warning should be issued to an endangered third party, the confidentiality of the communication that gave rise to the warning may be lost. Psychiatrists who have issued warnings have been compelled to testify in criminal cases (49).

KEY POINTS:

| • | The Supreme Court has ruled that communications between patient and psychotherapist are confidential in federal trials. | ||||

| • | State confidentiality statutes provide exceptions to maintaining the patient’s confidence in a variety of situations. | ||||

| • | Testimonial privilege belongs to the patient and protects confidential patient information in judicial settings. | ||||

| • | A patientlitigant exception exists when the patient places her or his mental state at issue in litigation. | ||||

| • | The purpose of the legal doctrine of informed consent is to promote patient autonomy. | ||||

| • | A substitute decision maker is necessary when a patient lacks health care decision-making capacity. | ||||

| • | An adult patient is considered legally competent unless adjudicated incompetent. | ||||

Testimonial privilege

The patient—not the psychiatrist—is the holder of the privilege that controls the release of confidential information. Because the privilege applies only to the judicial setting, it is called testimonial privilege. Privilege statutes represent the most common recognition by the state of the importance of protecting information provided by a patient to a psychotherapist. This recognition moves away from the essential purpose of the American system of justice (e.g., “truth finding”) by insulating certain information from disclosure in court. This protection is justified on the basis that the special need for privacy in the physician-patient relationship outweighs the unbridled quest for an accurate outcome in court.

Privilege statutes usually are drafted with reference to one of the following four relationships, depending on the type of practitioner:

| ■ | Physician-patient (general) | ||||

| ■ | Psychiatrist-patient | ||||

| ■ | Psychologist-patient | ||||

| ■ | Psychotherapist-patient | ||||

Cases have been successfully litigated in which the broader physician-patient category has been applied to the psychotherapist when an applicable statute did not exist.

Privilege statutes also specify exceptions to testimonial privilege. Although exceptions vary, the most common include the following:

| ■ | Child abuse reporting | ||||

| ■ | Civil commitment proceedings | ||||

| ■ | Court-ordered evaluations | ||||

| ■ | Cases in which a patient’s mental state is in question as a part of litigation | ||||

The last exception, known as the patient-litigant exception, commonly occurs in will contests, workers’ compensation cases, child custody disputes, personal injury actions, and malpractice actions in which the therapist is sued by the patient.

Liability

An unauthorized or unwarranted breach of confidentiality can cause a patient considerable emotional harm. As a result, a psychiatrist typically can be held liable for such a breach on the basis of at least four theories:

| ■ | Malpractice (breach of confidentiality) | ||||

| ■ | Breach of statutory duty | ||||

| ■ | Invasion of privacy | ||||

| ■ | Breach of (implied) contract | ||||

Informed consent and the right to refuse treatment

Informed consent is a legal theory in medical malpractice. It provides a patient with a cause of action for not being adequately informed about the nature and consequences of a particular medical treatment or procedure undertaken. This theory is founded on two distinct legal principles. The first is the right of every patient to determine what will or will not be done to his or her body, often referred to as the right of self-determination. The second principle emanates from the fiduciary nature of the physician-patient relationship. Inherent in a physician’s duty of fiduciary care is the responsibility to disclose honestly and in good faith all requisite facts concerning a patient’s condition. Included among factors to be disclosed are any treatment risks, alternatives, and consequences. The primary purpose of the doctrine of informed consent is to promote individual autonomy; secondarily, it is intended to promote rational decision making (50).

There are three essential elements to the doctrine of informed consent:

| ■ | Competency | ||||

| ■ | Information | ||||

| ■ | Voluntariness | ||||

Usually clinicians provide the first level of screening in identifying patient competency and in deciding whether to accept a patient’s treatment decision. The patient or a bona fide representative must be given an adequate description of the treatment. If the patient who refuses treatment appears to lack health care decision-making capacity, it does not mean that the patient cannot be treated. An appropriate substitute decision maker can provide (or withhold) consent. To be able to provide informed consent, the patient or substitute decision maker should be told about the risks, benefits, and prognosis both with and without treatment, as well as alternative treatments and their risks and benefits. In addition, the competent patient must voluntarily consent to or refuse the proposed treatment or procedure.

The legal doctrine of informed consent is consistent with the provision of good clinical care. The informed consent doctrine allows patients to become partners in making treatment determinations that accord with their own needs and values. In the past, physicians operated under the “do no harm” principle. Today, psychiatrists are increasingly required to practice within the model of informed consent and patient autonomy. Most psychiatrists find increased patient autonomy desirable in fostering the development of the therapeutic alliance that is so essential to treatment. Furthermore, patient autonomy is the goal of most psychiatric treatments (51).

Competency

It is clinically useful to distinguish the terms incompetence and incapacity. Incompetence refers to a court adjudication, whereas incapacity indicates a functional inability as determined by a clinician (34). Legally, only competent persons may give informed consent. An adult patient is considered legally competent unless adjudicated incompetent or temporarily incapacitated because of a medical emergency. Incapacity does not prevent treatment; it merely requires the clinician to obtain substitute consent. Treating an incompetent patient without substituted consent is the same as treating a competent patient against his or her will.

KEY POINTS:

| • | Treating an incompetent patient without substituted consent is the same as treating a competent patient against his or her will. | ||||

| • | Legal competence is narrowly defined as cognitive capacity. Psychiatrists generally prefer a rational decisionmaking standard in determining a patient’s mental incapacity for health care decision making. | ||||

Legal competence is narrowly defined as cognitive capacity. The definition derives largely from the laws governing transactions. Important clinical concepts such as affective incompetence are not usually recognized by the law unless cognitive capacity is significantly diminished. For example, a severely depressed but cognitively intact patient may refuse antidepressant medication owing to profound feelings of hopelessness, helplessness, and worthlessness. Manic patients emphasize risks of medications while downplaying benefits. Patients with schizophrenia tend to be fearful that medication will cause them serious harm. They are often unable to make a balanced assessment that considers both risks and benefits of a proposed drug. A study in which three instruments were used to assess competency for treatment decisions found that the schizophrenia and depression groups demonstrated poorer understanding of treatment disclosures, poorer reasoning in decision making regarding treatment, and a greater likelihood of failing to appreciate their illness or the potential treatment benefits (52). Denial of illness often interferes with insight and the ability to appreciate the significance of information provided to the patient.

Competency is not a scientifically determinable state and is situation specific. The issue of competency arises in a number of civil, criminal, and family law contexts. Although there are no hard-and-fast definitions, the patient’s ability to perform the following is legally germane to determining competency:

| ■ | Understand the particular treatment choice being proposed | ||||

| ■ | Make a treatment choice | ||||

| ■ | Communicate that choice verbally or nonverbally | ||||

This standard obtains only a simple consent from the patient rather than an informed consent, because alternative treatment choices are not addressed.

A review of case law and scholarly literature reveals four standards for determining mental incapacity in decision making (50). In order of increasing levels of mental capacity required, these standards are:

| ■ | Communication of choice | ||||

| ■ | Understanding of relevant information provided | ||||

| ■ | Appreciation of available options and consequences | ||||

| ■ | Rational decision making | ||||

Although some patients may communicate a choice and understand the information provided, they may lack the insight or ability to appreciate the information provided (53). Rational decision making is impaired as well. For example, patients with schizophrenia tend to fear some idiosyncratic harm from the treatment while ignoring the actual risk of medication side effects.

Psychiatrists generally feel most comfortable with a rational decision-making standard in determining patient incapacity for health care decision making. Most courts prefer the first two standards mentioned earlier but often combine competency standards. A truly informed consent that considers the patient’s autonomy, personal needs, and values occurs when rational decision making is applied by the patient to the risks and benefits of appropriate treatment options provided by the clinician.

Grisso and Appelbaum (52) found that the choice of standards determining competence affected the type and proportion of patients classified as impaired. When compound standards were used, the proportion of patients identified as impaired increased. These authors advised that clinicians be aware of the applicable standards in their jurisdictions.

A valid consent can be either expressed (oral or in writing) or implied from the patient’s actions. The competency issue is particularly sensitive when dealing with minors or mentally disabled persons who lack the requisite cognitive capacity for health care decision making. In both cases, it is generally recognized in the law that an authorized representative or guardian may consent for the patient (see Table 4).

Information