Relapse Prevention and Bipolar Disorder: A Focus on Bipolar Depression

Abstract

There is growing evidence that bipolar disorder and bipolar spectrum disorders are both prevalent and pernicious. They may cause profound impairment in all aspects of a patient’s life and frequently disrupt the structure of the patient’s entire social network. Beyond a consensus that most patients with bipolar disorder will require continuous treatment, relatively little is known about the long-term management of either bipolar I or bipolar II disorder. Although managing depression and depressive symptoms is the greatest challenge faced by patients with these disorders and the physicians who treat them, prevention of mania, rather than depression, has been the focus of most research efforts. This review article will summarize research evidence regarding the utility of lithium, anticonvulsant agents, antipsychotic medications, antidepressant medications, and electroconvulsive therapy in preventing relapse of depressive symptoms for patients with bipolar I and bipolar II disorders.

Definition of bipolar disorder

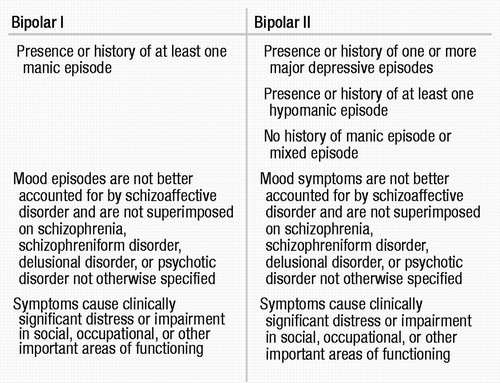

Bipolar disorder is a chronic mood disorder with unpredictable, recurrent episodes of mania, hypomania, and major depression. The course of the disease is erratic and varies according to both subtype and life stressors. Two subtypes of bipolar disorder are described in the DSM-IV-TR (1) (Table 1). Bipolar I disorder is characterized by the presence of at least one episode of mania and is usually accompanied by periods of major depressive disorder. Bipolar II disorder is characterized by the presence of at least one episode of hypomania. The presence of episodes of major depressive disorder is the same. Growing evidence supports the idea that subsyndromal forms of bipolar disorder, frequently referred to as bipolar spectrum disorder, are disabling and share genetic diatheses with bipolar I and bipolar II disorders. Although bipolar spectrum disorders cannot be adequately discussed within the context of this review, it is important to acknowledge that these spectrum forms of bipolar disorder are becoming an important area of investigation.

Epidemiology

The reported lifetime prevalence rates for bipolar disorder I range from 0.8% to 1.6% (2), while the prevalence rates for bipolar II disorder range from 0.5% to 1.9% (2). However, recent discussions in the literature suggest that these prevalence figures may be overly conservative. Hirschfeld summarized studies of what has been conceptualized as bipolar spectrum disorder (mania, hypomania, mixed states, hyperthymic temperament, and mixed depressive states) that report prevalence rates as high as 5% to 7% (3–6). These data, taken in their entirety, based on even the most parsimonious definitions of bipolar disorders, suggest that the bipolar disorders directly affect the lives of between 13 and 35 individuals per thousand adults in the United States. If we employ the more inclusive definition of bipolar spectrum disorder, these syndromes directly affect the lives of at least 70 individuals per thousand adults.

What makes these data even more compelling is recent evidence suggesting that relapse is very common following recovery from an acute episode of either mania or depression. Bipolar disorder is recurrent in up to 90% of patients (7), and, unfortunately, most patients with bipolar disorder suffer from an average of 0.6 relapses per year (8). In addition, the risk of suicide is extremely high in this population, with rates of attempted suicide ranging from 25% to 50% and estimates of completed suicides ranging from 9% to 60% (7). Thus, bipolar disorder and bipolar spectrum disorders are highly recurrent and affect the lives of not only those with the illness but all those who love and care for these individuals as well.

A theoretical framework for maintenance therapy

Post et al. proposed that bipolar disorder may be subject to a kindling-like phenomenon (9). The kindling hypothesis postulates that the course of bipolar disorder generally shows increasingly shorter periods of remission between episodes of illness, with later episodes more independent (“autonomous”) of environmental precipitants. This model postulates that patients become sensitized to very minor stressors, which play an increasing role in precipitating the onset of new mood episodes. For example, subsyndromal symptoms (milder symptoms of depression or mild hyperthymia) will increase the risk of disease recurrence (10). Post and colleagues suggested that treatment with mood stabilizers may favorably affect the course of the bipolar disorder by reducing kindling phenomena (9).

However, not all studies are supportive of the kindling hypothesis; a 10-year naturalistic follow-up study by Winokur et al. found that some patients, even patients with rapid cycling, experienced less frequent mood episodes over time (11). A recent analysis of the longitudinal bipolar data set from the Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic did not find that sensitization occurred as the number of episodes increased, nor do these data support the observation that the interepisode time decreased significantly in patients with bipolar disorder (12). Although these studies do not support the kindling hypothesis, the authors agree with the assertion that continuous treatment is reasonable for most patients with bipolar disorder.

The theoretical framework for understanding bipolar disorder has been in a state of transition over the last decade. It is now appreciated that bipolar disorder and bipolar spectrum disorders probably represent a constellation of biologically related, yet distinct, etiopathophysiologic entities. This would at least partially account for differences in age at onset, course, and treatment response. Another major transition has been more explicit: discussion of differences in the course of illness observed for patients with bipolar disorder. As is the case with hypertension or diabetes, most patients with bipolar disorder have illnesses that evolve and change over the patients’ lifetimes. Therefore, as with these other chronic syndromes, treatment interventions need to be flexible. The dosage and number of medications, as well as the frequency and intensity of psychotherapeutic interventions, must match the evolution (and phase) of the illness that the patient is in. These shifts in our theoretical framework have facilitated the development of maintenance treatment guidelines for bipolar disorder.

Progression in our thinking regarding the need for maintenance therapy

How psychiatrists manage bipolar disorder has evolved as longitudinal data have been published and new therapies have been developed. Most clinicians now believe that a substantial number of our patients with bipolar disorder require longer-term, if not indefinite, treatment. There has been a progression in the development of the nosology and the treatment recommendations for bipolar disorder, similar to what has occurred with major depressive disorder. The initial treatment guidelines for bipolar disorder distinguished between the continuation and maintenance phases of treatment in a way that was analogous to the recommendations for major depressive disorder (13). However, the American Psychiatric Association (APA) Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Bipolar Disorder (Revision) stated that this may be an artificial distinction for patients with bipolar disorder (14). The current guidelines suggest that the acute phase extends through the first 6 months of stabilization, and that the maintenance phase extends from that point forward. The most recent APA Practice Guideline recommends initiating maintenance therapy for all patients who have experienced a manic episode (14).

Long-term treatment strategies for bipolar II first were discussed in the 1996 Expert Consensus Guidelines, and these guidelines recommend that long-term, if not lifelong, therapy with a mood stabilizer be considered for individuals who have suffered three or more hypomanic episodes (13). A lower threshold for long-term treatment (e.g., one or two hypomanic episodes) was suggested for patients with a strong family history. Consensus about the need for long-term treatment of bipolar II disorders is still developing. Sachs and colleagues published recommendations that long-term treatment with a mood stabilizer be considered, irrespective of number of episodes, for bipolar II patients with the following: 1) antidepressant-induced mania or hypomania, 2) severe spontaneous hypomanic episodes, 3) frequent and severe depressions, 4) a strong family history of mania, and 5) a current need for antidepressant treatment (15). The most recent recommendations from the APA Practice Guideline suggest that maintenance therapy is “strongly warranted” for patients with bipolar II disorder but acknowledge the need for more research in this area (14).

Maintenance treatment strategies

A successful strategy for effective maintenance treatment for patients with bipolar disorder and bipolar spectrum disorders should include education, psychotherapy, and pharmacotherapy. Patient and family education is critically important in establishing rapport and enhancing adherence. Psychotherapeutic interventions may help patients establish regular patterns of behavior, normalize unstable relationships, and facilitate longer periods of euthymia. These efforts combined with individualized pharmacotherapy may greatly reduce the number and severity of episodes of mania and depression. This in turn enhances the quality of life of our patients, increases their productivity, and improves their psychosocial functioning.

Patient education and adherence

One of the most challenging tasks a clinician faces is educating patients and their families about psychiatric illness (13). This is particularly true for patients with bipolar disorders, who frequently enjoy the euphoria and increased productivity associated with hypomania. Many times these acutely symptomatic patients are in denial about the severity of their illness and the adverse consequences of their actions (16). Therefore, one of the critical interventions during the early phase of therapy is to educate the patient about the bipolar disorder, its prognosis, and our belief that collaborative maintenance therapy can help a patient regain control over his or her life. This education should engage the patient as an active partner in his or her treatment and must emphasize the need for collaborative work to enhance adherence (13). In order to appropriately tailor an educational program for a patient, a physician must have a working knowledge of risk factors associated with nonadherence. Risk factors that predispose patients toward nonadherence include denial of the illness, substance use disorders, greater severity of illness (episodes of greater severity and greater number of episodes), greater complexity of the medication regimen, and the occurrence of medication-induced side effects (17, 18). Medication-induced adverse effects, such as weight gain, sexual dysfunction, cognitive dysfunction, and renal and thyroid problems, are significant problems for many patients. Frank discussion of the potential side effects as well as plans to ameliorate them, when and if they do occur, can greatly increase adherence.

Psychosocial therapy

It has been well established that a patient’s social and occupational functioning can remain significantly diminished despite substantial and even sustained symptomatic improvement (19). New research suggests that psychotherapy may be critically important in helping patients return to normal function and thus should be a component of treatment for most patients with bipolar disorder (14). Adjunctive individual supportive therapy, cognitive behavioral therapy, psychodynamic therapy, and interpersonal therapy, as well as family therapy and group therapy, may be useful for patients with bipolar disorder (14). Psychosocial interventions may also reduce suicidal behavior in bipolar patients (20, 21). Many smaller studies have explored the use of psychosocial treatment concomitant with mood stabilizer therapy; however, the more commonly used supportive and psychodynamic-eclectic therapies have not been explored in randomized controlled trials (14). There is more published work suggesting that specifically developed individual psychotherapies for patients with bipolar disorder may improve longitudinal outcomes. Individual psychoeducational interventions (22, 23), family-focused education (24), interpersonal psychotherapy (25), and social rhythm therapy have all been reported to decrease the frequency of episodes and increase the quality of patients’ lives.

Social rhythm therapy, an individual psychotherapy designed specifically for the treatment of bipolar disorder, grew out of a chronobiological mode of bipolar illness (26, 27). Administered in conjunction with medication, social rhythm therapy combines principles of interpersonal psychotherapy with behavioral techniques to help patients regularize their routines. This therapy aims to modulate both biological and psychological factors that affect patients’ circadian and sleep-wake cycles. In bipolar patients, disruptions of these cycles may be partially responsible for symptoms of the illness (25). Frank and Kupfer and colleagues have demonstrated significant improvements in patients receiving interpersonal and social rhythm therapy (28, 29). In particular, they described the use of phase-specific sequenced psychotherapies linked to fluctuating mood states (30). Their data even suggest that interpersonal and social rhythm therapy may facilitate a significant decrease in suicidal behavior in high-risk patients with bipolar disorder (20).

The importance of psychosocial interventions should not be underestimated; they help stabilize patients, improve psychosocial functioning, and increase adherence. In fact, there are some data suggesting that abrupt discontinuation of psychotherapy may even precipitate relapse in some patients (16). Therefore, although psychosocial therapy alone clearly does not convey long-term protection from recurrences of mania and depression (16), it seems to be a critically important adjunct to pharmacotherapy that enhances the treatment of the patient.

The appropriate intensity for any of the psychotherapies has not yet been determined. The National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD) may begin to answer some of these questions. However, an older version of the treatment guidelines suggests that the frequency of psychotherapy visits may need to be as often as once to twice weekly for patients who are severely ill and once a month or less for patients with milder forms of the disorder (13). Peer support groups run by advocacy groups, such as the National Depressive and Manic-Depressive Association and the National Alliance for the Mentally Ill, may serve as a vital adjuvant to formal psychotherapy (14).

Pharmacotherapy

Placebo-controlled trials evaluating maintenance therapy of bipolar disorder fell out of favor in the 1970s because such studies were difficult to perform and there were no new agents that merited the time and expense necessary to conduct the research (31, 32). In fact, there was a two-decade hiatus between the publication of the last lithium maintenance treatment data and the initiation of the recent maintenance treatment studies for bipolar disorder.

Lithium is the only agent approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for maintenance treatment and for many years has been the mainstay of prophylactic therapy for patients with bipolar disorder. The early trials performed under the umbrella of the Perry Point Veterans Administration Study Group reported that lithium was more effective than placebo in diminishing the frequency of episodes of both mania and major depression (33, 34). These studies established the benchmark for all the recently initiated long-term prophylaxis studies. They also began to define the characteristics of the ideal mood stabilizer for maintenance therapy: one that decreases the frequency of episodes of both depression and mania (16, 35).

A serious challenge of maintenance therapy is treating breakthrough depression (7). Bipolar depression is associated with greater morbidity and mortality than pure mania, yet there is relatively little long-term treatment research (36) to guide the development of recommendations for the prophylactic management of bipolar depression. Although valproate (divalproex) and carbamazepine are effective antimanic agents, only lithium has been determined to adequately treat both poles of the disorder. However, lithium’s efficacy in bipolar depression may be incomplete, and lithium may not consistently prevent breakthrough depression. More data about medications that manage bipolar depression without increasing the risk of mania are sorely needed.

Research regarding maintenance treatment for bipolar II disorder is even more limited, and many current recommendations are based on findings from bipolar I patients. Because these two subtypes differ significantly, research to determine the best treatment interventions for both of these entities is important for better patient care (7, 37). To the extent the literature permits, the discussion that follows presents data for both bipolar I and bipolar II disorders.

An overview of treatment considerations

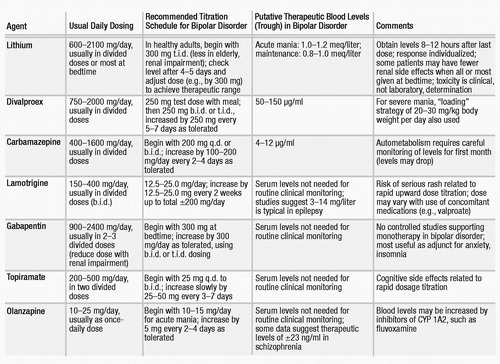

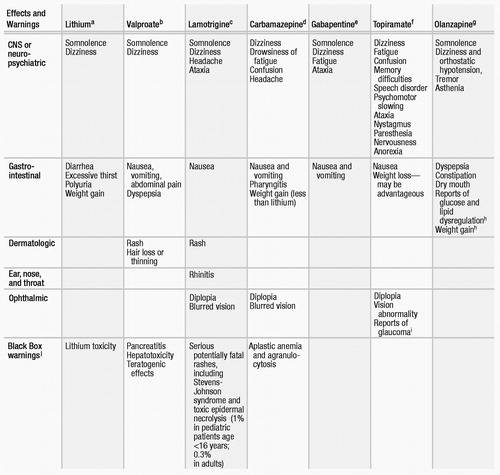

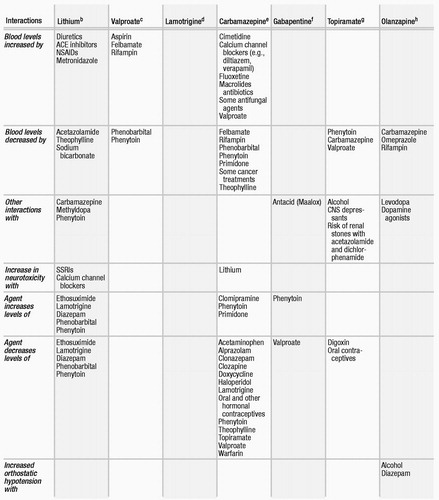

A review of the basic pharmacology of the compounds used for maintenance treatment trials for bipolar disorder will improve appreciation of the results of the studies cited here. Table 2 lists the dose ranges, blood levels, and titration schedules for lithium, the anticonvulsant medications, and olanzapine. Table 3 lists the common side effect profiles for these compounds, and Table 4 summarizes the common drug-drug interactions associated with these medications. Since it has become increasingly common for bipolar patients to be maintained on combination therapy, an understanding of the common adverse effects and potential pharmacokinetic interactions is critical to ensure good clinical care of our patients.

Lithium

Lithium has been used for many years as both an acute and a prophylactic treatment for bipolar I and bipolar II disorders. Although there are definitive data demonstrating the acute efficacy of lithium for bipolar disorder, there is a rather heated controversy about its efficacy as a prophylactic treatment for bipolar disorder. This controversy about the long-term effectiveness of lithium has been addressed from a number of different perspectives. Some authors have investigated the question of whether lithium treatment decreases the frequency of episodes of mania and depression, while others have explored whether lithium has become less effective in preventing episodes of mania and depression over the last few decades. Both of these approaches are valid, but the results are best considered when interpreted within a larger context.

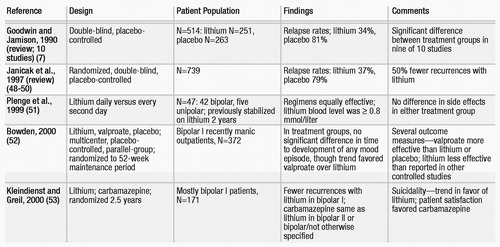

Bipolar disorder is most likely a heterogeneous syndrome with a variety of different etiopathophysiologic causes. Therefore, different patients with this syndrome will respond differently to various treatment interventions. Consequently, the study of any sample of convenience may have some intrinsic variance because of sampling bias. A second factor that may explain a portion of the difference in results over the last few decades is that many lithium-responsive patients are being seen and treated in the general community. These patients are not entering trials and frequently do not participate in the naturalistic studies reported from larger institutions. A third factor that may account for some of the discrepancies in reported lithium response rates is the evolving definition of bipolar disorder. Many more patients are classified as bipolar today than back in the 1960s and 1970s. Thus, the increased heterogeneity of sample patient populations over time may increase the variability observed in treatment response for any given sample. A fourth factor is differences in study design. Many of the older studies employed a crossover design in which patients stabilized on lithium were abruptly discontinued and switched to placebo, possibly resulting in higher placebo relapse rates (32). Table 5 summarizes the results of reviews and meta-analyses investigating the longer-term efficacy of lithium.

Efficacy

Studies that have focused on lithium’s effectiveness as a prophylactic agent for protection against bipolar depression are generally positive. Baldessarini and Tondo reviewed 11 controlled and 13 open long-term lithium treatment trials conducted between 1970 and 1996 for bipolar or mixed major affective disorders (54). They selected only studies that would permit estimates of recurrence rates, with and without lithium treatment. Recurrences per month for various types of bipolar patients not taking lithium were, on average, 18.7-fold higher than for those receiving lithium. Perhaps even more striking, they found that 65.6% of all subjects showed major benefits from lithium treatment, as indicated by a 50% or greater reduction in the percentage of time ill.

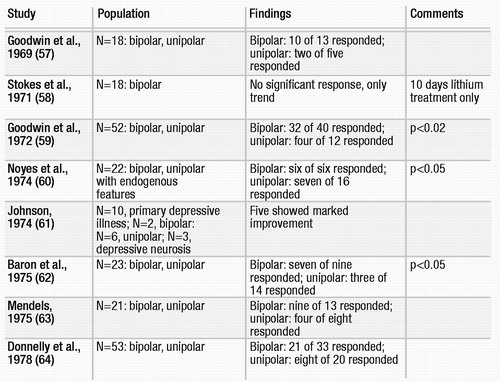

Goodwin and Jamison and Strakowski et al. have reviewed controlled studies of lithium use for depression (7, 55). Goodwin and Jamison’s review of seven studies that specifically explored depressive recurrence included investigations of unipolar as well as bipolar depressed patients (total N=164) (7). Overall, the response rate was 79% for bipolar depression. Summarizing controlled studies after 1971, Strakowski et al. found a wide range of response rates to lithium in bipolar depression, varying from 44% to 100% (55). While they reported an overall response rate of 72% for patients with bipolar depression, many of these patients had partial responses and did not achieve remission. Nevertheless, Strakowski and colleagues concluded, “Lithium has been the most widely studied antidepressant treatment in bipolar disorder and appears to be effective without the risk of inducing mania or rapid cycling associated with other antidepressants.” Therefore, in summary, there is some consensus that lithium may be moderately effective for prophylaxis of bipolar depression (56), but, not unexpectedly, breakthrough depressions will occur in a significant number of patients (36). Table 6 summarizes the results of placebo-controlled trials investigating lithium treatment of bipolar depression.

In contrast to the studies cited above that investigated the question of whether lithium is more effective than placebo treatment for the maintenance treatment of bipolar disorder, other studies have examined whether lithium’s efficacy to prevent episodes of relapse and recurrence diminished over time. Recent studies suggest that lithium’s efficacy as a prophylactic treatment for the prevention of mood episodes in bipolar patients has diminished over the last 25 years (65, 66). Failure rates for lithium maintenance monotherapy have ranged from 42% to 64% (10). In one naturalistic study by Maj and colleagues, only 23% of bipolar patients were relapse-free and only 14% had no subsyndromal symptoms during a 5-year period of lithium treatment (67). These results differ from an analysis contained in the Baldessarini and Tondo review (54). These authors reported that the percentage of subjects who had a 50% or greater reduction in the percentage of time ill had not changed significantly over the decades studied (54). Further studies are needed to clarify this issue. Data from the NIMH Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD) may help resolve some of these questions.

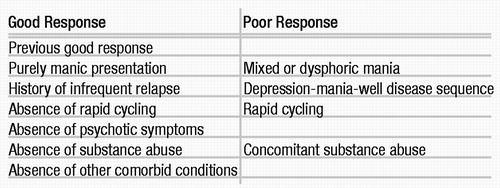

Because of concern over the longer-term effectiveness of lithium as a prophylactic agent, a number of post hoc analyses have been performed as part of the search to identify clinical variables related to moderate lithium responsiveness. Table 7 summarizes factors reported to be associated with good and poor responses to lithium treatment. As would be expected, not all studies support these post hoc findings. A large retrospective/naturalistic study by Tondo and colleagues examined 360 bipolar I and II patients with predominantly mixed, psychotic, and rapid-cycling features (68). Tondo et al. found that lithium was an effective maintenance therapy over the course of 1 year, even in these subtypes of bipolar patients.

Any review of lithium pharmacotherapy would be incomplete if it did not acknowledge the recent analysis by Tondo and Baldessarini of 22 studies conducted from 1974 to 1998, which examined lithium’s effect on suicidality (69). They found a seven-fold reduction in suicide rates for patients during long-term lithium treatment, compared with 1) patients in these studies when they were not receiving lithium; 2) patients not receiving lithium treatment; or 3) patients after lithium discontinuation. Although these data are incomplete, lithium treatment seemed to reduce the rate of suicide and suicide attempts to that of the general population.

In summary, data suggest that lithium maintenance treatment is effective in decreasing the number and frequency of mood episodes in some bipolar patients. However, it is clear that lithium prophylaxis is not completely effective in preventing relapse in the majority of bipolar patients. It will be important to determine variables that are predictive of a positive long-term response to lithium treatment.

Use with bipolar I versus bipolar II disorder

There are no large-scale placebo-controlled trials that compare and contrast the efficacy of lithium monotherapy in bipolar I and bipolar II subjects. Most of the data comparing the efficacy of lithium for these disorders come from case reports and retrospective naturalistic follow-up studies. The majority of the most recent work has come from the group at McLean Hospital. Although there is a commonly held belief that lithium is not effective for bipolar II disorder, this notion is not supported by the existing data. In a retrospective study of 188 bipolar I and 129 bipolar II patients, Tondo et al. found that the protective effect of lithium on the prevention of manic and hypomanic recurrences was greater for bipolar II patients than for bipolar I patients (70). Lithium treatment also led to greater reductions in the frequency of depressive episodes and in the total percentage of time that bipolar II patients spent in episodes. When this same research group examined 360 lithium-treated type I and II bipolar patients with predominantly mixed, psychotic, and rapid-cycling features, they found that bipolar type II patients spent less time ill than bipolar type I patients (6.5% versus 22%, respectively) (68). This suggests that lithium therapy may facilitate stabilization of some patients with bipolar II disorder to at least the same extent as, if not more than, is seen in bipolar I disorder.

Valproate

There are few controlled trials evaluating long-term treatment with valproate. Nevertheless, its use as maintenance therapy in bipolar disorder has increased greatly in the United States over the last decade (71).

Efficacy

Open-label trials report that long-term combination treatment with valproate does decrease the frequency of mood episodes, but its efficacy as long-term monotherapy for bipolar disorder remains to be proven (38, 72–74). One small open-label study of 55 rapid-cycling patients found that valproate treatment was effective for short- and long-term management of mania but was 30% less effective for the management of depression (72). In a 78-patient follow-up report, Calabrese and colleagues found that prophylactic treatment with valproate produced a marked response in 76% of manic patients but in only 48% of patients with bipolar depression. This led the investigators to conclude that valproate has at best a minimal-to-moderate antidepressant effect (38). The recent prospective, randomized, double-blind study that compared lithium with divalproex and placebo in patients with bipolar I disorder who had experienced an episode of mania or hypomania during the prior 12 weeks was the first maintenance study to be reported in the literature (37). Surprisingly, the time to development of any mood episode did not differ significantly among the three treatment groups, though a trend was observed favoring divalproex over lithium. Median time to a mood episode was 40 weeks with divalproex versus 24 weeks with lithium and 28 weeks with placebo. However, concerns were raised about the design of this study. The inclusion criteria for this study may have selected patients with milder forms of bipolar disorder, which may have led to the larger-than-expected placebo response rate. This large placebo response rate meant that the sample size of the study was not large enough to ensure adequate statistical power to differentiate a definitive treatment effect for divalproex (37, 75).

Use with bipolar I versus bipolar II disorder

In their 1990 study, Calabrese and Delucchi found that bipolar II patients fared better with valproate therapy than did bipolar I patients (72). Ninety-three percent of bipolar II patients were acute treatment responders in this study versus 84% of bipolar I patients. Marked response was defined as cessation of all cycling (no breakthroughs of any kind), while moderate response was defined as improvement in cycle severity, duration, or frequency (i.e., there was persistence of mood swings). The difference in treatment effect was even more profound when patients were categorized by marked response: 77% of bipolar II patients exhibited marked improvement versus 56% of bipolar I patients in this open augmentation trial (72).

Puzynski and Klosiewicz studied the prophylactic effect of open-label valproate in 15 lithium-nonresponsive patients (five with bipolar I disorder, five with bipolar II disorder, and five with schizoaffective disorder) (74). During the 26–51 months of treatment, the number and length of affective episodes, especially manias, dramatically decreased for the group as a whole (from 68 to 37). In this open-label trial, the number of manic episodes decreased from 19 to 10 in the bipolar I patients, but occurrence of depressive episodes did not decrease (13 versus 12 episodes). The authors did not report the number of hypomanic episodes for the bipolar II patients, but there was a substantial reduction in the number of depressive episodes for the bipolar II patients (from six to one). It is clear that more large-scale placebo-controlled trials are needed to evaluate the longer-term efficacy of valproic acid treatment for both bipolar I and bipolar II disorders (66).

Carbamazepine

Carbamazepine was the first anticonvulsant widely studied for the treatment of bipolar disorder. However, with the approval of divalproex for the treatment of bipolar disorder and the development of newer anticonvulsant medications that have more benign side effect profiles, the use of carbamazepine has diminished.

Efficacy

Although the anticonvulsant carbamazepine is frequently prescribed in Europe, few randomized placebo-controlled studies exist regarding its efficacy for maintenance therapy in bipolar disorder. Ketter et al. reviewed 13 controlled or partially controlled studies of carbamazepine prophylaxis conducted between 1978 and 1992 and found an overall response rate of 68% in 132 subjects (76). This review, and another by Nemeroff (77), suggests that carbamazepine, used either as monotherapy or in combination with other agents, may decrease the recurrence of episodes of both mania and depression. These conclusions are supported by longitudinal data from Post and colleagues, who found that 55% of severely ill bipolar patients treated with carbamazepine continued to do well over a 3-year follow-up assessment period (78).

There have been few head-to-head comparison studies of carbamazepine. Two relatively small studies found no difference in efficacy between long-term carbamazepine and lithium treatment (79, 80).

Use with bipolar I versus bipolar II disorder

The majority of the carbamazepine prophylaxis studies were performed before the DSM-IV criteria for bipolar I versus bipolar II were developed. However, Kleindienst and Greil reported the results of a randomized, 2.5-year maintenance study comparing lithium with carbamazepine in 171 bipolar patients (114 with bipolar I, 57 with bipolar II/not otherwise specified) (53). In this study lithium treatment decreased the frequency of mood episodes more than carbamazepine treatment for bipolar I patients. The two treatment conditions had similar efficacy for the bipolar II/not otherwise specified group. In a second analysis the sample was recategorized into two groups: “classical” bipolar I (no mood-incongruent delusions or comorbidity) and “nonclassical” bipolar disorder (bipolar II and all other patients). The “classical” bipolar patients randomly assigned to lithium treatment had significantly lower rates of hospitalization. There was a trend suggesting that carbamazepine treatment decreased the rate of hospitalization for “nonclassical” bipolar patients.

Lamotrigine

Lamotrigine is an antiepileptic with FDA-approved labeling as monotherapy or adjunctive therapy in adults with partial seizures and as adjunctive therapy in the generalized seizures of Lennox-Gastaut syndrome in pediatric and adult patients. Anecdotal observations that lamotrigine improved mood, social interaction, and general well-being of patients with epilepsy stimulated the development of a double-blind crossover trial that confirmed there was improvement in quality of life and mood (81, 82). These findings encouraged psychiatrists to investigate the potential benefits of lamotrigine treatment for patients with bipolar disorders.

Efficacy

There have been 21 case reports or open-label uncontrolled studies of lamotrigine treatment for bipolar disorder (35, 83–86). More than 300 patients who seemed to be representative of the breadth of the spectrum of bipolar disorder (bipolar depression, hypomania, and mixed state; bipolar I and II subtypes; treatment-refractory and rapid-cycling patients; and bipolar patients with comorbid attention deficit hyperactivity disorder) were investigated in these reports. These uncontrolled reports suggested that lamotrigine might be an effective agent for the treatment of a number of phases of the illness and possibly a number of different subtypes of patients, including those with bipolar depression, hypomania, and mixed bipolar states (35).

There have been three large-scale placebo-controlled maintenance studies investigating the efficacy of lamotrigine in delaying the recurrence of mood episodes in patients with bipolar disorder (87–89). At this time, data from two of the trials, a maintenance study in rapid-cycling bipolar patients and a maintenance study in previously manic bipolar patients, have been published or accepted for publication. All three of the trials had a similar design, and so the methodology of the published trial for the treatment of rapid-cycling bipolar patients is presented in detail. After an open-label phase in which lamotrigine was added to rapid-cycling bipolar patients’ current regimens, stabilized patients (N=182) were tapered off other medications (87). If they continued to be euthymic for 1 month, they entered into a 6-month, double-blind, randomized phase comparing placebo discontinuation with lamotrigine monotherapy. Time to additional pharmacotherapy was the primary outcome measure, and on this measure lamotrigine and placebo did not statistically separate. However, when survival in the study was evaluated for the study population, a statistically significantly greater number of lamotrigine-treated subjects continued in the trial (87). In the maintenance study for recently manic bipolar I patients, continued lamotrigine treatment during the double-blind discontinuation phase was statistically superior to placebo treatment on four outcome measures: time to intervention for any mood episode, overall survival in study, time to any bipolar event, and time to a depressive episode (88). These data suggest that lamotrigine may be an important treatment option for maintenance treatment of bipolar disorder, particularly for the prevention of bipolar depression.

Use with bipolar I versus bipolar II disorder

Secondary analyses of the rapid-cycling bipolar study were conducted focusing on whether there were differences in treatment outcome for bipolar I and bipolar II patients (87). There were no significant differences on outcome measures for bipolar I patients treated with either lamotrigine or placebo. However, lamotrigine treatment of bipolar II patients was associated with statistically meaningful trends suggesting that lamotrigine treatment increased the time until additional pharmacotherapy was needed, as well as the overall survival in the study (41% of patients in the lamotrigine group versus 26% in the placebo group).

Gabapentin

Gabapentin is an antiepileptic structurally similar to γ-aminobutyric acid. It is indicated as add-on therapy for patients with partial seizures. Gabapentin is widely used as an augmentation treatment for patients with chronic pain and has been studied in both anxiety disorders and bipolar disorder.

Efficacy

Open-label studies suggest that adjunctive treatment with gabapentin may help in the acute management of mood disorders (90). Schaffer and Schaffer published follow-up data on 18 patients with refractory bipolar disorder who initially responded to gabapentin augmentation (91). Seven of 18 patients (39%) remained episode-free over an average of 33 months.

There have been very few controlled trials with gabapentin. Frye and colleagues, in a randomized placebo-controlled comparison of gabapentin and lamotrigine in the treatment of acute mania, found that gabapentin did not separate from placebo (42). In a second trial, a placebo-controlled study of gabapentin augmentation of patients with acute mania, gabapentin treatment again did not separate from placebo treatment (92). Further research of this drug’s efficacy is needed, but the clinical impression is that its greatest utility in bipolar disorder may be as an adjunctive treatment for insomnia or agitation (56).

Use with bipolar I versus bipolar II disorder

Controlled data of gabapentin monotherapy in bipolar I and bipolar II subtypes are very limited. However, naturalistic data suggest that gabapentin may possess efficacy in nonrefractory bipolar II disorder (6).

Other anticonvulsants as putative mood stabilizers

Several other anticonvulsants are being investigated as potential mood stabilizers. Topiramate is popular as an augmentation agent for bipolar disorder. In the largest of the open studies investigating topiramate treatment of bipolar disorder, Marcotte evaluated 58 bipolar spectrum patients (bipolar I, bipolar II, mixed, and not otherwise specified) (40). He reported that 52% of these subjects demonstrated some benefit from topiramate therapy. The majority of the subjects who had a positive response were receiving topiramate as an adjunctive medication with a variety of other psychotropic agents. A recent randomized pilot study compared topiramate to bupropion in depressed bipolar I and bipolar II patients. Topiramate was prescribed as monotherapy and bupropion as adjuvant therapy to lithium or divalproex. Fifty-six percent of the topiramate-treated patients and 59% of the bupropion-treated patients had at least a 50% decrease from baseline in 17-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression scores (93). Discontinuation was higher in the topiramate group (44% versus 28%), but none of the subjects in either group switched into mania during the study (93). Maintenance studies for the prophylaxis against mood episodes have not yet been performed.

Oxcarbazepine, the keto-analogue of carbamazepine, has been reported to have significant antimanic activity, according to several European studies (94). These data suggest that oxcarbazepine has antimanic effects comparable to those of lithium and haloperidol. However, there is very limited controlled evidence available regarding the use of oxcarbazepine for bipolar depression or as a maintenance treatment for bipolar disorder.

Interest has also been generated in the use of tiagabine, levetiracetam, and zonisamide as possible mood stabilizers. Preliminary studies are being performed to investigate the acute efficacy of these agents, but controlled maintenance studies investigating their efficacy in the prophylaxis against mood episodes have not been conducted to date.

Combination mood-stabilizer therapy

The use of combination therapy in the acute treatment of bipolar disorder has increased dramatically: Frye et al. reported in 2000 that 70% of lithium prescriptions were written in combination with other medications (65). The percentage of patients receiving three or more medications increased from 3.3% in 1974–1979 to 43.8% in 1990–1995 (65). These findings are not surprising and are consistent with the recent recommendations from expert panels. The Expert Consensus Guidelines 2000 recommend combining mood stabilizers when monotherapy fails for both acute mania and bipolar depression (15). Unfortunately, at this time there are no specific recommendations about what combinations of therapies are most effective. According to the APA Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Bipolar Disorder (Revision), there is currently insufficient research information to recommend the use of one combination over another (14).

Although small open-label investigations and case reports suggest that a combination of mood stabilizers may be effective in the long-term treatment of bipolar patients, there have been only two large combination therapy trials published to date. Denicoff et al. compared carbamazepine, lithium, and the combination in the prophylactic treatment of bipolar I and bipolar II patients (39). Neither of the monotherapies was clearly superior, although there was some suggestion that lithium treatment was a better prophylaxis against recurrence of episodes of mania than carbamazepine treatment. The study did find that combination treatment was better than monotherapy, especially for the treatment of rapid-cycling patients. The treatment options did not prevent the recurrence of bipolar depression. Bipolar I and bipolar II patients did not differ in their response to the three treatment options (39).

In 1994, Peselow and colleagues reported that patients who relapsed on lithium monotherapy had a better acute and maintenance response to combination therapy (lithium plus neuroleptic, lithium plus carbamazepine, or lithium plus benzodiazepine) than monotherapy. Forty-six percent of patients who had previously relapsed into mania with lithium monotherapy remained well with the combination of lithium plus carbamazepine (N=13) (95).

Antipsychotics: long-term treatment

Both classical neuroleptic medication (“typical” antipsychotics) and newer atypical antipsychotic medication are often used for acute and maintenance treatment of bipolar disorder (96). However, their role in the prophylaxis of mood episodes in bipolar patients is still being defined, and, as yet, no antipsychotic has FDA-approved labeling for this indication.

There are no currently published controlled trials demonstrating the effectiveness of antipsychotic medication monotherapy in the long-term treatment of bipolar disorder. Indeed, open-label studies actually show an increase in depressive relapse with conventional antipsychotic use for bipolar disorder (96). Atypical antipsychotic medication may be more useful as a maintenance therapy for bipolar disorder, but atypical antipsychotic monotherapy has not been studied in controlled clinical trials. In a naturalistic comparison (N=50) of clozapine, risperidone, and olanzapine as adjunctive therapy for bipolar disorder, the three agents were found to have equivalent efficacy (97). Other case reports and open study data investigating clozapine support these clinical findings and suggest that it may be useful either as monotherapy or as an adjunct to mood stabilizers for the long-term treatment of bipolar disorder (98–100). However, Banov and colleagues found that a history of depressive episodes prior to administration of clozapine significantly predicted the drug’s discontinuation (98). Suppes and colleagues also suggested that clozapine had limited antidepressant activity in their study (100).

Research investigating the long-term efficacy of olanzapine in bipolar disorder also is limited. Tohen and colleagues reported encouraging results from a 1-year, open-label, follow-up study of patients who initially participated in an acute mania trial (101). The mania ratings of these patients continued to improve with continued olanzapine treatment; however, one-third of the patients required the addition of lithium and another third required the addition of an antidepressant (96). Recently, Vieta et al. studied long-term adjunctive therapy with olanzapine in 23 subjects with treatment-resistant bipolar I and bipolar II disorders (102). The introduction of olanzapine (mean dose=8.1 mg/day) was associated with a significant reduction in Clinical Global Impression (CGI) scores, either in manic, depressive, or global symptoms.

A 6-month follow-up study of risperidone augmentation treatment of 12 bipolar I patients with breakthrough symptoms of mood instability, hypomania, and/or depression found mild-to-moderate improvement in four patients and a depressive relapse in one patient (103). A case report (104) and a small pilot study (105) raised a concern about whether risperidone might exacerbate mania in a small percentage of patients. However, Goodwin and Ghaemi suggested that these cases reflect the inappropriate use of monotherapy, with atypical antipsychotic medications leading to “unmasking” of bipolar (manic) symptoms (6).

Additional placebo-controlled, randomized studies are needed to evaluate the short-term and long-term efficacy of atypical antipsychotic medications as both monotherapies and part of combination therapy for bipolar disorder.

Antidepressants

A tremendous controversy exists about what constitutes appropriate use of antidepressant medication for patients with bipolar disorder. There is significant concern that antidepressant medications may increase the risk of switches into mania. However, depression and subsyndromal depression are significant problems for many bipolar patients. These episodes tend to be persistent and disabling. No prospective, controlled data are available assessing the utility of long-term antidepressant therapy for bipolar disorder (96). However, there is clear agreement that antidepressants should not be used as monotherapy in bipolar disorder (14), since switches into mania may occur in 70% of patients (96). Many experts suggest that antidepressants should be used for the shortest time possible in bipolar patients, and if manic symptoms develop, the dose of the antidepressant medication should be immediately reduced if not completely discontinued (15, 106). Ghaemi and colleagues reported that antidepressant use was associated with a worsened course of bipolar illness and seemed to induce rapid cycling, thus supporting these recommendations (107). A recent retrospective chart review by Altshuler and colleagues, however, found that termination of antidepressant medication significantly increased the risk of a depressive relapse in bipolar patients (108). Clearly, more research is needed investigating the use of antidepressant medication in bipolar disorder.

Electroconvulsive therapy

There is very little controlled maintenance research investigating electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) for bipolar disorder; indeed, much of the work that is available was conducted 40 to 50 years ago. In a naturalistic study, Kramer reported on the effects of maintenance ECT in a heterogeneous group of psychiatric patients, including both unipolar and bipolar patients (109). One-third of patients remained much improved and 77.8% experienced partial improvement compared with baseline. It is of interest that the patients with bipolar disorder required maximum stimulus intensity to obtain sustained benefit.

Conclusions

Bipolar disorder is a chronic and often refractory illness that may be associated with an increasing number of relapses over time. The disease causes significant morbidity and mortality and therefore requires long-term prophylaxis. Unfortunately, bipolar disorder is a heterogeneous syndrome, and the long-term prognosis and response to treatment vary widely among patients. For many years lithium was the only option available for long-term treatment of bipolar disorder, and, as would be expected, many patients suffered from recurrences of both mania and depression. We now have a variety of newer therapeutic approaches available for the treatment of bipolar disorder; however, controlled clinical trials with other mood stabilizers commonly used as maintenance therapy in bipolar disorder have not been performed.

Despite differences in long-term response to treatment for mania and bipolar depression, most maintenance formulations do not contain specific strategies for each pole. Bipolar depression is more difficult to control and is associated with a greater degree of morbidity; thus, effective prophylactic therapy is critical in the management of this disorder. Although the primary mood-stabilizing agents (i.e., lithium, valproate, and carbamazepine) are effective for treatment of acute mania, their antidepressant efficacy for acute bipolar depression is more limited. These agents also have limited prophylactic protection against the recurrence of bipolar depression. Thus, there is interest in investigating newer agents such as lamotrigine and topiramate for the treatment of bipolar depression.

Further research in the area of maintenance therapy for bipolar disorder is the key to establishing the most effective treatment options. To that end, a number of investigations are under way. Several Cochrane Systematic Reviews are evaluating the use of lithium, valproate, and carbamazepine in the prophylaxis of bipolar disorder. Additionally, the Bipolar Affective Disorder: Lithium Anticonvulsant Evaluation (BALANCE) study, a large-scale randomized trial currently in the pilot phase, will evaluate long-term use of the combination of lithium and valproate versus either drug as monotherapy (71). Furthermore, NIMH has now funded a large (N=5,000) study—the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD). This will involve approximately 100–200 treating psychiatrists in about 20 treatment centers in the United States and will follow patients for 3 to 5 years. Hopefully, these studies, as well as additional trials with newer agents, will provide further direction for the maintenance treatment of bipolar disorder.

Disclosure of Unapproved or Investigational Use of a Product APA policy requires disclosure of unapproved or investigational uses of products discussed in CME programs. As of the date of publication of this CME program, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration has approved lithium for the treatment of patients with bipolar disorder; maprotiline for the treatment of bipolar disorder, depressed type; and divalproex for the treatment of bipolar disorder, manic episodes. All other uses are “off-label.” Off-label use of medications by individual physicians is permitted and common. Decisions about off-label use can be guided by the scientific literature and clinical experience.

|

Table 1. Diagnostic Criteria for Bipolar I and Bipolar II Disordersa

|

Table 2. Mood Stabilizers: Use in Bipolar Disordera

|

Table 3. Common Side Effect Profiles of Medications Frequently Used in Bipolar Disorder

|

Table 4. Common Drug Interactions of Medications Frequently Used in Bipolar Disordera

|

Table 5. Published Controlled Studies of Lithium Maintenance for Bipolar Disorder

|

Table 6. Randomized Placebo-Controlled Studies of Lithium in Bipolar Depression

|

Table 7. Factors Associated With Good and Poor Responses to Lithiuma

1 American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR). Washington, DC, APA, 2000Google Scholar

2 Angst J: The emerging epidemiology of hypomania and bipolar II disorder. J Affect Disord 1998; 50:143–151Crossref, Google Scholar

3 Hirschfeld RM: Bipolar spectrum disorder: improving its recognition and diagnosis. J Clin Psychiatry 2001; 62(suppl 14):5–9Google Scholar

4 Akiskal HS, Bourgeois ML, Angst J, Post R, Moller H, Hirschfeld R: Re-evaluating the prevalence of and diagnostic composition within the broad clinical spectrum of bipolar disorders. J Affect Disord 2000; 59(suppl 1):S5–S30Crossref, Google Scholar

5 Akiskal HS: The prevalent clinical spectrum of bipolar disorders: beyond DSM-IV. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1996; 16(2 suppl 1):4S–14SCrossref, Google Scholar

6 Goodwin FK, Ghaemi SN: The difficult-to-treat patient with bipolar disorder, in The Difficult-to-Treat Psychiatric Patient. Edited by Dewan MJ, Pies RW. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 2001, pp 7–39Google Scholar

7 Goodwin F, Jamison K: Manic-Depressive Illness. New York, Oxford University Press, 1990Google Scholar

8 Winokur G, Coryell W, Keller M, Endicott J, Akiskal H: A prospective follow-up of patients with bipolar and primary unipolar affective disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1993; 50:457–465Crossref, Google Scholar

9 Post RM, Rubinow DR, Ballenger JC: Conditioning, sensitization, and kindling: implications for the course of affective illness, in Neurobiology of Mood Disorders. Edited by Post RM, Ballenger JC. Baltimore, Williams & Wilkins, 1984, pp 432–466Google Scholar

10 Solomon DA, Keitner GI, Miller IW, Shea MT, Keller MB: Course of illness and maintenance treatments for patients with bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 1995; 56:5–13Google Scholar

11 Winokur G, Coryell W, Akiskal HS, Endicott J, Keller M, Mueller T: Manic-depressive (bipolar) disorder: the course in light of a prospective ten-year follow-up of 131 patients. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1994; 89:102–110Crossref, Google Scholar

12 Hlastala SA, Frank E, Kowalski J, Sherrill JT, Tu XM, Anderson B, Kupfer DJ: Stressful life events, bipolar disorder, and the “kindling model.” J Abnorm Psychol 2000; 109:777–786Crossref, Google Scholar

13 Frances A, Docherty JP, Kahn DA: Treatment of bipolar disorder: the Expert Consensus Panel for Bipolar Disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 1996; 57(suppl 12A):3–88Google Scholar

14 American Psychiatric Association: Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Bipolar Disorder (Revision). Am J Psychiatry2002; 159 (April suppl)Google Scholar

15 Sachs GS, Printz DJ, Kahn DA, Carpenter D, Docherty JP: The Expert Consensus Guidelines series: medication treatment of bipolar disorder, 2000. Postgraduate Medicine 2000 ; Special Issue: 1 –104Google Scholar

16 Sachs GS: Bipolar mood disorder: practical strategies for acute and maintenance phase treatment. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1996; 16(2 suppl 1):32S–47SCrossref, Google Scholar

17 Keck PE Jr, McElroy SL, Strakowski SM, Stanton SP, Kizer DL, Balistreri TM, Bennett JA, Tugrul KC, West SA: Factors associated with pharmacologic noncompliance in patients with mania. J Clin Psychiatry 1996; 57:292–297Google Scholar

18 Keck PE Jr, McElroy SL, Strakowski SM, Bourne ML, West SA: Compliance with maintenance treatment in bipolar disorder. Psychopharmacol Bull 1997; 33:87–91Google Scholar

19 Suppes T, Dennehy EB, Gibbons EW: The longitudinal course of bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2000; 61(suppl 9):23–30Google Scholar

20 Rucci P, Frank E, Kostelnik B, Fagiolini A, Mallinger AG, Swartz HA, Thase ME, Siegel L, Wilson D, Kupfer DJ: Suicide attempts in patients with bipolar I disorder during acute and maintenance phases of intensive treatment with pharmacotherapy and adjunctive psychotherapy. Am J Psychiatry 2002; 159:1160–1164Crossref, Google Scholar

21 Gray SM, Otto MW: Psychosocial approaches to suicide prevention: applications to patients with bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2001; 62(suppl 25):56–64Google Scholar

22 Bauer MS, McBride L, Chase C, Sachs G, Shea N: Manual-based group psychotherapy for bipolar disorder: a feasibility study. J Clin Psychiatry 1998; 59:449–455Crossref, Google Scholar

23 Perry A, Tarrier N, Morriss R, McCarthy E, Limb K: Randomised controlled trial of efficacy of teaching patients with bipolar disorder to identify early symptoms of relapse and obtain treatment. Br Med J 1999; 318:149–153Crossref, Google Scholar

24 Miklowitz DJ, Simoneau TL, George EL, Richards JA, Kalbag A, Sachs-Ericsson N, Suddath R: Family-focused treatment of bipolar disorder: 1-year effects of a psychoeducational program in conjunction with pharmacotherapy. Biol Psychiatry 2000; 48:582–592Crossref, Google Scholar

25 Frank E, Novick D: Progress in the psychotherapy of mood disorders: studies from the Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic. Epidemiol Psichiatr Soc 2001; 10:245–252Crossref, Google Scholar

26 Jones SH: Circadian rhythms, multilevel models of emotion and bipolar disorder—an initial step towards integration? Clin Psychol Rev 2001; 21:1193–1209Crossref, Google Scholar

27 Malkoff-Schwartz S, Frank E, Anderson BP, Hlastala SA, Luther JF, Sherrill JT, Houck PR, Kupfer DJ: Social rhythm disruption and stressful life events in the onset of bipolar and unipolar episodes. Psychol Med 2000; 30:1005–1016Crossref, Google Scholar

28 Frank E, Swartz H, Kupfer D: Interpersonal and social rhythm therapy: managing the chaos of bipolar disorder. Biol Psychiatry 2000; 48:593–604Crossref, Google Scholar

29 Frank E, Kupfer DJ, Gibbons R, Houck P, Kostelnik B, Mallinger AG, Swartz HA, Thase ME: Interpersonal and social rhythm therapy prevents depressive symptomatology in patients with bipolar I disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry (in press)Google Scholar

30 Swartz HA, Frank E: Psychotherapy for bipolar depression: a phase-specific treatment strategy? Bipolar Disord 2001; 3:11–22Crossref, Google Scholar

31 Goodwin GM: Prophylaxis of bipolar disorder: how and who should we treat in the long term? Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 1999; 9(suppl 4):S125–S129Crossref, Google Scholar

32 Calabrese JR, Rapport DJ, Shelton MD, Kimmel SE: Evolving methodologies in bipolar disorder maintenance research. Br J Psychiatry Suppl 2001; 41:S157–S163Google Scholar

33 Prien RF, Caffey EM Jr, Klett CJ: Prophylactic efficacy of lithium carbonate in manic-depressive illness: report of the Veterans Administration and National Institute of Mental Health Collaborative Study Group. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1973; 28:337–341Crossref, Google Scholar

34 Prien RF, Caffey EM Jr, Klett CJ: Factors associated with treatment success in lithium carbonate prophylaxis: report of the Veterans Administration and National Institute of Mental Health Collaborative Study Group. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1974; 31:189–192Crossref, Google Scholar

35 Calabrese JR, Rapport DJ, Shelton MD, Kujawa M, Kimmel SE: Clinical studies on the use of lamotrigine in bipolar disorder. Neuropsychobiology 1998; 38:185–191Crossref, Google Scholar

36 Kalin NH: Management of the depressive component of bipolar disorder. Depress Anxiety 1996; 4:190–198Crossref, Google Scholar

37 Bowden CL, Calabrese JR, McElroy SL, Gyulai L, Wassef A, Petty F, Pope HG Jr, Schou JC, Keck PE Jr, Rhodes LJ, Swann AC, Hirschfeld RM, Wozniak PJ: A randomized, placebo-controlled 12-month trial of divalproex and lithium in treatment of outpatients with bipolar I disorder: Divalproex Maintenance Study Group. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2000; 57:481–489Crossref, Google Scholar

38 Calabrese JR, Markovitz PJ, Kimmel SE, Wagner SC: Spectrum of efficacy of valproate in 78 rapid-cycling bipolar patients. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1992; 12(suppl 1):53S–56SCrossref, Google Scholar

39 Denicoff KD, Smith-Jackson EE, Disney ER, Ali SO, Leverich GS, Post RM: Comparative prophylactic efficacy of lithium, carbamazepine, and the combination in bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 1997; 58:470–478Crossref, Google Scholar

40 Marcotte D: Use of topiramate, a new anti-epileptic, as a mood stabilizer. J Affect Disord 1998; 50:245–251Crossref, Google Scholar

41 Chong E, Dupuis LL: Therapeutic drug monitoring of lamotrigine. Ann Pharmacother 2002; 36:17–20Crossref, Google Scholar

42 Frye MA, Ketter TA, Kimbrell TA, Dunn RT, Speer AM, Osuch EA, Luckenbaugh DA, Cora-Locatelli G, Leverich GS, Post RM: A placebo-controlled study of lamotrigine and gabapentin monotherapy in refractory mood disorders. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2000; 20:607–614Crossref, Google Scholar

43 Hurley SC: Lamotrigine update and its use in mood disorders. Ann Pharmacother 2002; 36:860–873Crossref, Google Scholar

44 Arana GW, Rosenbaum JF: Handbook of Psychiatric Drug Therapy, 4th ed. Philadelphia, Lippincott William & Wilkins, 2000Google Scholar

45 McIntyre RS, McCann SM, Kennedy SH: Antipsychotic metabolic effects: weight gain, diabetes mellitus, and lipid abnormalities. Can J Psychiatry 2001; 46:273–281Crossref, Google Scholar

46 Rhee DJ, Goldberg MJ, Parrish RK: Bilateral angle-closure glaucoma and ciliary body swelling from topiramate. Arch Ophthalmol 2001; 119:1721–1723Google Scholar

47 Sankar PS, Pasquale LR, Grosskreutz CL: Uveal effusion and secondary angle-closure glaucoma associated with topiramate use. Arch Ophthalmol 2001; 119:1210–1211Google Scholar

48 Janicak PG, Davis JM, Preskorn SH, Ayd FJ: Treatment with mood stabilizers: management of an acute manic episode, in Principles and Practice of Psychopharmacotherapy. Edited by Gay S. Baltimore, Williams & Wilkins, 1997, pp 412–428Google Scholar

49 Janicak PG, Davis JM, Preskorn SH, Ayd FJ: Treatment with mood stabilizers: maintenance/prophylaxis, in Principles and Practice of Psychopharmacotherapy. Edited by Gay S. Baltimore, Williams & Wilkins, 1997, pp 428–441Google Scholar

50 Janicak PG, Davis JM, Preskorn SH, Ayd FJ: Adverse effects of lithium and valproate, in Principles and Practice of Psychopharmacotherapy. Edited by Gay S. Baltimore, Williams & Wilkins, 1997, pp 461–468Google Scholar

51 Plenge P, Amin M, Agarwal AK, Greil W, Kim MJ, Panteleyeva G, Park JM, Prilipko L, Rayushkin V, Sharma M, Mellerup E: Prophylactic efficacy of lithium administered every second day: a WHO multicentre study. Bipolar Disord 1999; 1:109–116Crossref, Google Scholar

52 Bowden CL: Efficacy of lithium in mania and maintenance therapy of bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2000; 61(suppl 9):35–40Google Scholar

53 Kleindienst N, Greil W: Differential efficacy of lithium and carbamazepine in the prophylaxis of bipolar disorder: results of the MAP study. Neuropsychobiology 2000; 42(suppl 1):2–10Crossref, Google Scholar

54 Baldessarini RJ, Tondo L: Does lithium treatment still work? evidence of stable responses over three decades. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2000; 57:187–190Crossref, Google Scholar

55 Strakowski SM, McElroy SL, Keck PE: Clinical efficacy of valproate in bipolar illness: comparisons and contrasts with lithium, in Pharmacotherapy for Mood, Anxiety, and Cognitive Disorders. Edited by Halbreich U, Montgomery SA. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 2000, pp 143–157Google Scholar

56 Compton MT, Nemeroff CB: The treatment of bipolar depression. J Clin Psychiatry 2000; 61(suppl 9):57–67Google Scholar

57 Goodwin FK, Murphy DL, Bunney WE Jr: Lithium-carbonate treatment in depression and mania: a longitudinal double-blind study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1969; 21:486–496Crossref, Google Scholar

58 Stokes PE, Shamoian CA, Stoll PM, Patton MJ: Efficacy of lithium as acute treatment of manic-depressive illness. Lancet 1971; 1:1319–1325Crossref, Google Scholar

59 Goodwin FK, Murphy DL, Dunner DL, Bunney WE: Lithium response in unipolar versus bipolar depression. Am J Psychiatry 1972; 129:76–79Google Scholar

60 Noyes R Jr, Dempsey GM, Blum A, Cavanaugh GL: Lithium treatment of depression. Compr Psychiatry 1974; 15:187–193Crossref, Google Scholar

61 Johnson G: Antidepressant effect of lithium. Compr Psychiatry 1974; 15:43–47Crossref, Google Scholar

62 Baron M, Gershon ES, Rudy V, Jonas WZ, Buchsbaum M: Lithium carbonate response in depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1975; 32:1107–1111Crossref, Google Scholar

63 Mendels J: Lithium in the treatment of depressive states, in Lithium Research and Therapy. Edited by Johnson FN. New York, Academic Press, 1975, pp 43–62Google Scholar

64 Donnelly EF, Goodwin FK, Waldman IN, Murphy DL: Prediction of antidepressant responses to lithium. Am J Psychiatry 1978; 135:552–556Crossref, Google Scholar

65 Frye MA, Ketter TA, Leverich GS, Huggins T, Lantz C, Denicoff KD, Post RM: The increasing use of polypharmacotherapy for refractory mood disorders: 22 years of study. J Clin Psychiatry 2000; 61:9–15Crossref, Google Scholar

66 Post RM, Leverich GS, Denicoff KD, Frye MA, Kimbrell TA, Dunn R: Alternative approaches to refractory depression in bipolar illness. Depress Anxiety 1997; 5:175–189Crossref, Google Scholar

67 Maj M, Pirozzi R, Magliano L, Bartoli L: Long-term outcome of lithium prophylaxis in bipolar disorder: a 5-year prospective study of 402 patients at a lithium clinic. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:30–35Crossref, Google Scholar

68 Tondo L, Baldessarini RJ, Floris G: Long-term clinical effectiveness of lithium maintenance treatment in types I and II bipolar disorders. Br J Psychiatry Suppl 2001; 41:S184–S190Google Scholar

69 Tondo L, Baldessarini RJ: Reduced suicide risk during lithium maintenance treatment. J Clin Psychiatry 2000; 61(suppl 9):97–104Google Scholar

70 Tondo L, Baldessarini RJ, Hennen J, Floris G: Lithium maintenance treatment of depression and mania in bipolar I and bipolar II disorders. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:638–645Crossref, Google Scholar

71 Geddes J, Goodwin G: Bipolar disorder: clinical uncertainty, evidence-based medicine and large-scale randomised trials. Br J Psychiatry Suppl 2001; 41:S191–S194Crossref, Google Scholar

72 Calabrese JR, Delucchi GA: Spectrum of efficacy of valproate in 55 patients with rapid-cycling bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1990; 147:431–434Crossref, Google Scholar

73 Hayes SG: Long-term valproate prophylaxis in refractory affective disorders. Ann Clin Psychiatry 1992; 4:55–63Crossref, Google Scholar

74 Puzynski S, Klosiewicz L: Valproic acid amide in the treatment of affective and schizoaffective disorders. J Affect Disord 1984; 6:115–121Crossref, Google Scholar

75 Baldessarini RJ, Tohen M, Tondo L: Maintenance treatment in bipolar disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2000; 57:490–492Crossref, Google Scholar

76 Ketter TA, Post RM, Denicoff K, Pazzaglia PJ, Marangell LB, George MS, Callahan AM: Carbamazepine, in Mania: Clinical and Research Perspectives. Edited by Goodnick P. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1998, pp 263–300Google Scholar

77 Nemeroff CB: An ever-increasing pharmacopoeia for the management of patients with bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2000; 61(suppl 13):19–25Google Scholar

78 Post RM, Denicoff KD, Frye MA, Leverich GS, Cora-Locatelli G, Kimbrell TA: Long-term outcome of anticonvulsants in affective disorders, in Bipolar Disorders: Clinical Course and Outcome. Edited by Goldberg JF, Harrow M. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1999, pp 85–114Google Scholar

79 Coxhead N, Silverstone T, Cookson J: Carbamazepine versus lithium in the prophylaxis of bipolar affective disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1992; 85:114–118Crossref, Google Scholar

80 Simhandl C, Denk E, Thau K: The comparative efficacy of carbamazepine low and high serum level and lithium carbonate in the prophylaxis of affective disorders. J Affect Disord 1993; 28:221–231Crossref, Google Scholar

81 Smith D, Baker G, Davies G, Dewey M, Chadwick DW: Outcomes of add-on treatment with lamotrigine in partial epilepsy. Epilepsia 1993; 34:312–322Crossref, Google Scholar

82 Edwards KR, Sackellares JC, Vuong A, Hammer AE, Barrett PS: Lamotrigine monotherapy improves depressive symptoms in epilepsy: a double-blind comparison with valproate. Epilepsy and Behavior 2001; 2:28–36Crossref, Google Scholar

83 Bowden CL, Calabrese JR, McElroy SL, Rhodes LJ, Keck PE Jr, Cookson J, Anderson J, Bolden-Watson C, Ascher J, Monaghan E, Zhou J: The efficacy of lamotrigine in rapid cycling and non–rapid cycling patients with bipolar disorder. Biol Psychiatry 1999; 45:953–958Crossref, Google Scholar

84 Calabrese JR, Rapport DJ: Mood stabilizers and the evolution of maintenance study designs in bipolar I disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 1999; 60(suppl 5):5–13Crossref, Google Scholar

85 Suppes T, Brown ES, McElroy SL, Keck PE Jr, Nolen W, Kupka R, Frye M, Denicoff KD, Altshuler L, Leverich GS, Post RM: Lamotrigine for the treatment of bipolar disorder: a clinical case series. J Affect Disord 1999; 53:95–98Crossref, Google Scholar

86 Walden J, Schaerer L, Schloesser S, Grunze H: An open longitudinal study of patients with bipolar rapid cycling treated with lithium or lamotrigine for mood stabilization. Bipolar Disord 2000; 2:336–339Crossref, Google Scholar

87 Calabrese JR, Suppes T, Bowden CL, Sachs GS, Swann AC, McElroy SL, Kusumakar V, Ascher JA, Earl NL, Greene PL, Monaghan ET: A double-blind, placebo-controlled, prophylaxis study of lamotrigine in rapid-cycling bipolar disorder: Lamictal 614 Study Group. J Clin Psychiatry 2000; 61:841–850Crossref, Google Scholar

88 Calabrese JR, Bowden C, DeVeaughy-Geiss J, Earl N, Gyulai L, Montgomery P: Lamotrigine demonstrates long-term mood stabilization in recently manic patients, in 2001 Annual Meeting Syllabus and Proceedings Summary. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 2001Google Scholar

89 Bowden CL, Ascher JA, Calabrese JR, Ginsburg A, Greene P, Montgomery F, et al: Lamotrigine: evidence for mood stabilization in bipolar I depression, in 2001 Annual Meeting Syllabus and Proceedings Summary. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 2001Google Scholar

90 Ferrier IN: Lamotrigine and gabapentin: alternative in the treatment of bipolar disorder. Neuropsychobiology 1998; 38:192–197Crossref, Google Scholar

91 Schaffer CB, Schaffer LC: Open maintenance treatment of bipolar disorder spectrum patients who responded to gabapentin augmentation in the acute phase of treatment. J Affect Disord 1999; 55:237–240Crossref, Google Scholar

92 Pande AC, Crockatt JG, Janney CA, Werth JL, Tsaroucha G: Gabapentin in bipolar disorder: a placebo-controlled trial of adjunctive therapy: Gabapentin Bipolar Disorder Study Group. Bipolar Disord 2000; 2(3 part 2):249–255Crossref, Google Scholar

93 McIntyre RS, Mancini DA, McCann S, Srinivasan J, Sagman D, Kennedy SH: Topiramate versus bupropion SR when added to mood stabilizer therapy for the depressive phase of bipolar disorder: a preliminary single-blind study. Bipolar Disord 2002; 4:207–213Crossref, Google Scholar

94 Emrich HM: Studies with oxcarbazepine (Trileptal) in acute mania, in Carbamazepine and Oxcarbazepine in Psychiatry. Edited by Emrich HM, Schiwy W, Silverstone T. London, Clinical Neuroscience Publishers, 1990, pp 83–88Google Scholar

95 Peselow ED, Fieve RR, Difiglia C, Sanfilipo MP: Lithium prophylaxis of bipolar illness: the value of combination treatment. Br J Psychiatry 1994; 164:208–214Crossref, Google Scholar

96 Sachs GS, Thase ME: Bipolar disorder therapeutics: maintenance treatment. Biol Psychiatry 2000; 48:573–581Crossref, Google Scholar

97 Guille C, Sachs GS, Ghaemi SN: A naturalistic comparison of clozapine, risperidone, and olanzapine in the treatment of bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2000; 61:638–642Crossref, Google Scholar

98 Banov MD, Zarate CA Jr, Tohen M, Scialabba D, Wines JD Jr, Kolbrener M, Kim JW, Cole JO: Clozapine therapy in refractory affective disorders: polarity predicts response in long-term follow-up. J Clin Psychiatry 1994; 55:295–300Google Scholar

99 Zarate CA Jr, Tohen M, Baldessarini RJ: Clozapine in severe mood disorders. J Clin Psychiatry 1995; 56:411–417Google Scholar

100 Suppes T, Webb A, Paul B, Carmody T, Kraemer H, Rush AJ: Clinical outcome in a randomized 1-year trial of clozapine versus treatment as usual for patients with treatment-resistant illness and a history of mania. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:1164–1169Google Scholar

101 Tohen M, Sanger TM, McElroy SL, Tollefson GD, Chengappa KNR, Daniel DG, Petty F, Centorrino F, Wang R, Grundy SL, Greaney MG, Jacobs TG, David SR, Toma V (Olanzapine HGEH Study Group): Olanzapine versus placebo in the treatment of acute mania. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:702–709Google Scholar

102 Vieta E, Reinares M, Corbella B, Benabarre A, Gilaberte I, Colom F, Martinez-Aran A, Gasto C, Tohen M: Olanzapine as long-term adjunctive therapy in treatment-resistant bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2001; 21:469–473Crossref, Google Scholar

103 Ghaemi SN, Sachs GS: Long-term risperidone treatment in bipolar disorder: 6-month follow-up. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 1997; 12:333–338Crossref, Google Scholar

104 Dwight MM, Keck PE Jr, Stanton SP, Strakowski SM, McElroy SL: Antidepressant activity and mania associated with risperidone treatment of schizoaffective disorder. Lancet 1994; 344:554–555Crossref, Google Scholar

105 Sajatovic M, DiGiovanni SK, Bastani B, Hattab H, Ramirez LF: Risperidone therapy in treatment refractory acute bipolar and schizoaffective mania. Psychopharmacol Bull 1996; 32:55–61Google Scholar

106 Bauer MS, Callahan AM, Jampala C, Petty F, Sajatovic M, Schaefer V, Wittlin B, Powell BJ: Clinical practice guidelines for bipolar disorder from the Department of Veterans Affairs. J Clin Psychiatry 1999; 60:9–21Crossref, Google Scholar

107 Ghaemi SN, Boiman EE, Goodwin FK: Diagnosing bipolar disorder and the effect of antidepressants: a naturalistic study. J Clin Psychiatry 2000; 61:804–808Crossref, Google Scholar

108 Altshuler L, Kiriakos L, Calcagno J, Goodman R, Gitlin M, Frye M, Mintz J: The impact of antidepressant discontinuation versus antidepressant continuation on 1-year risk for relapse of bipolar depression: a retrospective chart review. J Clin Psychiatry 2001; 62:612–616Crossref, Google Scholar

109 Kramer BA: A naturalistic review of maintenance ECT at a university setting. J ECT 1999; 15:262–269Google Scholar